Republic of Ireland

Ireland (Irish: Éire [ˈeːɾʲə] (![]() listen)), also known as the Republic of Ireland (Poblacht na hÉireann),[a] is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. Around 2.1 million of the country's population of 5.13 million people resides in the Greater Dublin Area.[10] The sovereign state shares its only land border with Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom. It is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, with the Celtic Sea to the south, St George's Channel to the south-east, and the Irish Sea to the east. It is a unitary, parliamentary republic.[11] The legislature, the Oireachtas, consists of a lower house, Dáil Éireann; an upper house, Seanad Éireann; and an elected President (Uachtarán) who serves as the largely ceremonial head of state, but with some important powers and duties. The head of government is the Taoiseach (Prime Minister, literally 'Chief', a title not used in English), who is elected by the Dáil and appointed by the President; the Taoiseach in turn appoints other government ministers.

listen)), also known as the Republic of Ireland (Poblacht na hÉireann),[a] is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. Around 2.1 million of the country's population of 5.13 million people resides in the Greater Dublin Area.[10] The sovereign state shares its only land border with Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom. It is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, with the Celtic Sea to the south, St George's Channel to the south-east, and the Irish Sea to the east. It is a unitary, parliamentary republic.[11] The legislature, the Oireachtas, consists of a lower house, Dáil Éireann; an upper house, Seanad Éireann; and an elected President (Uachtarán) who serves as the largely ceremonial head of state, but with some important powers and duties. The head of government is the Taoiseach (Prime Minister, literally 'Chief', a title not used in English), who is elected by the Dáil and appointed by the President; the Taoiseach in turn appoints other government ministers.

Ireland[a] | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Amhrán na bhFiann "The Soldiers' Song" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Dublin 53°20.65′N 6°16.05′W |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2016[2]) | |

| Religion (2016[3]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Irish |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Michael D. Higgins | |

| Micheál Martin | |

• Tánaiste | Leo Varadkar |

• Chief Justice | Donal O'Donnell |

| Legislature | Oireachtas |

| Seanad | |

| Dáil | |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

• Proclamation | 24 April 1916 |

• Declaration | 21 January 1919 |

| 6 December 1921 | |

• 1922 constitution | 6 December 1922 |

| 29 December 1937 | |

• Republic Act | 18 April 1949 |

| Area | |

• Total | 70,273 km2 (27,133 sq mi) (118th) |

• Water (%) | 2.0% |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | |

• 2016 census | 4,761,865[5] |

• Density | 71.3/km2 (184.7/sq mi) (113th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2021 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | low · 23rd |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 8th |

| Currency | Euro (€)[c] (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC (GMT) |

| UTC+1 (IST) | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +353 |

| ISO 3166 code | IE |

| Internet TLD | .ie[d] |

| |

The Irish Free State was created, with Dominion status, in 1922 following the Anglo-Irish Treaty. In 1937, a new constitution was adopted, in which the state was named "Ireland" and effectively became a republic, with an elected non-executive president. It was officially declared a republic in 1949, following the Republic of Ireland Act 1948. Ireland became a member of the United Nations in December 1955. It joined the European Communities (EC), the predecessor of the European Union, in 1973. The state had no formal relations with Northern Ireland for most of the twentieth century, but during the 1980s and 1990s the British and Irish governments worked with the Northern Ireland parties towards a resolution to "the Troubles". Since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, the Irish government and Northern Ireland Executive have co-operated on a number of policy areas under the North/South Ministerial Council created by the Agreement.

One of Europe's major financial hubs is centred on Dublin. Ireland ranks among the top ten wealthiest countries in the world in terms of GDP per capita,[12] although this has been partially ascribed to distortions caused by the tax inversion practices of various multinationals operating in Ireland.[13][14][15][16] From 2017, a modified gross national income (GNI*) was enacted by the Central Bank of Ireland, as the standard deviation was considered too materially distorted to accurately measure or represent the Irish economy.[17][18] After joining the EC, the country's government enacted a series of liberal economic policies that resulted in economic growth between 1995 and 2007 now known as the Celtic Tiger period, before its subsequent reversal during the Great Recession.[19]

A developed country, Ireland's quality of life is ranked amongst the highest in the world, and the country performs well in several national performance metrics including healthcare, economic freedom and freedom of the press.[20][21] Ireland is a member of the European Union and is a founding member of the Council of Europe and the OECD. The Irish government has followed a policy of military neutrality through non-alignment since immediately prior to World War II and the country is consequently not a member of NATO,[22] although it is a member of Partnership for Peace and aspects of PESCO.

Name

The Irish name for Ireland is Éire, deriving from Ériu, a goddess in Irish mythology.[23] The state created in 1922, comprising 26 of the 32 counties of Ireland, was "styled and known as the Irish Free State" (Saorstát Éireann).[24] The Constitution of Ireland, adopted in 1937, says that "the name of the State is Éire, or, in the English language, Ireland". Section 2 of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948 states, "It is hereby declared that the description of the State shall be the Republic of Ireland." The 1948 Act does not name the state "Republic of Ireland", because to have done so would have put it in conflict with the Constitution.[25]

The government of the United Kingdom used the name "Eire" (without the diacritic) and, from 1949, "Republic of Ireland", for the state.[26] It was not until the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, when the state dropped its claim to Northern Ireland, that it began calling the state "Ireland".[27][28]

As well as "Ireland", "Éire" or "the Republic of Ireland", the state is also informally called "the Republic", "Southern Ireland" or "the South";[29] especially when distinguishing the state from the island or when discussing Northern Ireland ("the North"). Irish republicans reserve the name "Ireland" for the whole island,[28] and often refer to the state as "the Free State", "the 26 Counties",[28][30] or "the South of Ireland".[31] This is a "response to the partitionist view [...] that Ireland stops at the border".[32]

History

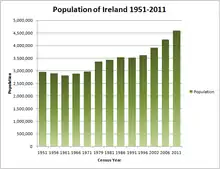

Home-rule movement

From the Act of Union on 1 January 1801, until 6 December 1922, the island of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. During the Great Famine, from 1845 to 1849, the island's population of over 8 million fell by 30%. One million Irish died of starvation and/or disease and another 1.5 million emigrated, mostly to the United States.[33] This set the pattern of emigration for the century to come, resulting in constant population decline up to the 1960s.[34][35][36]

From 1874, and particularly under Charles Stewart Parnell from 1880, the Irish Parliamentary Party gained prominence. This was firstly through widespread agrarian agitation via the Irish Land League, that won land reforms for tenants in the form of the Irish Land Acts, and secondly through its attempts to achieve Home Rule, via two unsuccessful bills which would have granted Ireland limited national autonomy. These led to "grass-roots" control of national affairs, under the Local Government Act 1898, that had been in the hands of landlord-dominated grand juries of the Protestant Ascendancy.

Home Rule seemed certain when the Parliament Act 1911 abolished the veto of the House of Lords, and John Redmond secured the Third Home Rule Act in 1914. However, the Unionist movement had been growing since 1886 among Irish Protestants after the introduction of the first home rule bill, fearing discrimination and loss of economic and social privileges if Irish Catholics achieved real political power. In the late 19th and early 20th-century unionism was particularly strong in parts of Ulster, where industrialisation was more common in contrast to the more agrarian rest of the island, and where the Protestant population was more prominent, with a majority in four counties.[37] Under the leadership of the Dublin-born Sir Edward Carson of the Irish Unionist Party and the Ulsterman Sir James Craig of the Ulster Unionist Party, unionists became strongly militant in order to oppose "the Coercion of Ulster".[38] After the Home Rule Bill passed parliament in May 1914, to avoid rebellion with Ulster, the British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith introduced an Amending Bill reluctantly conceded to by the Irish Party leadership. This provided for the temporary exclusion of Ulster from the workings of the bill for a trial period of six years, with an as yet undecided new set of measures to be introduced for the area to be temporarily excluded.

Revolution and steps to independence

Though it received the Royal Assent and was placed on the statute books in 1914, the implementation of the Third Home Rule Act was suspended until after the First World War which defused the threat of civil war in Ireland. With the hope of ensuring the implementation of the Act at the end of the war through Ireland's engagement in the war, Redmond and the Irish National Volunteers supported the UK and its Allies. 175,000 men joined Irish regiments of the 10th (Irish) and 16th (Irish) divisions of the New British Army, while Unionists joined the 36th (Ulster) divisions.[39]

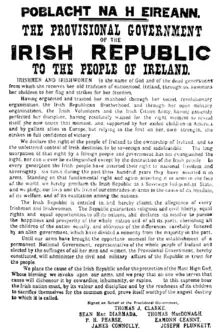

The remainder of the Irish Volunteers, who refused Redmond and opposed any support of the UK, launched an armed insurrection against British rule in the 1916 Easter Rising, together with the Irish Citizen Army. This commenced on 24 April 1916 with the declaration of independence. After a week of heavy fighting, primarily in Dublin, the surviving rebels were forced to surrender their positions. The majority were imprisoned but fifteen of the prisoners (including most of the leaders) were executed as traitors to the UK. This included Patrick Pearse, the spokesman for the rising and who provided the signal to the volunteers to start the rising, as well as James Connolly, socialist and founder of the Industrial Workers of the World union and both the Irish and Scottish Labour movements. These events, together with the Conscription Crisis of 1918, had a profound effect on changing public opinion in Ireland against the British Government.[40]

In January 1919, after the December 1918 general election, 73 of Ireland's 106 Members of Parliament (MPs) elected were Sinn Féin members who refused to take their seats in the British House of Commons. Instead, they set up an Irish parliament called Dáil Éireann. This first Dáil in January 1919 issued a Declaration of independence and proclaimed an Irish Republic. The Declaration was mainly a restatement of the 1916 Proclamation with the additional provision that Ireland was no longer a part of the United Kingdom. The Irish Republic's Ministry of Dáil Éireann sent a delegation under Ceann Comhairle (Head of Council, or Speaker, of the Daíl) Seán T. O'Kelly to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, but it was not admitted.

After the War of Independence and truce called in July 1921, representatives of the British government and the five Irish treaty delegates, led by Arthur Griffith, Robert Barton and Michael Collins, negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty in London from 11 October to 6 December 1921. The Irish delegates set up headquarters at Hans Place in Knightsbridge, and it was here in private discussions that the decision was taken on 5 December to recommend the treaty to Dáil Éireann. On 7 January 1922, the Second Dáil ratified the Treaty by 64 votes to 57.[41]

In accordance with the treaty, on 6 December 1922 the entire island of Ireland became a self-governing Dominion called the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann). Under the Constitution of the Irish Free State, the Parliament of Northern Ireland had the option to leave the Irish Free State one month later and return to the United Kingdom. During the intervening period, the powers of the Parliament of the Irish Free State and Executive Council of the Irish Free State did not extend to Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland exercised its right under the treaty to leave the new Dominion and rejoined the United Kingdom on 8 December 1922. It did so by making an address to the King requesting, "that the powers of the Parliament and Government of the Irish Free State shall no longer extend to Northern Ireland."[42] The Irish Free State was a constitutional monarchy sharing a monarch with the United Kingdom and other Dominions of the British Commonwealth. The country had a governor-general (representing the monarch), a bicameral parliament, a cabinet called the "Executive Council", and a prime minister called the President of the Executive Council.

Irish Civil War

.jpg.webp)

The Irish Civil War (June 1922 – May 1923) was the consequence of the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the creation of the Irish Free State.[43] Anti-treaty forces, led by Éamon de Valera, objected to the fact that acceptance of the treaty abolished the Irish Republic of 1919 to which they had sworn loyalty, arguing in the face of public support for the settlement that the "people have no right to do wrong".[44] They objected most to the fact that the state would remain part of the British Empire and that members of the Free State Parliament would have to swear what the Anti-treaty side saw as an oath of fidelity to the British King. Pro-treaty forces, led by Michael Collins, argued that the treaty gave "not the ultimate freedom that all nations aspire to and develop, but the freedom to achieve it".[45]

At the start of the war, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) split into two opposing camps: a pro-treaty IRA and an anti-treaty IRA. The pro-treaty IRA disbanded and joined the new National Army. However, because the anti-treaty IRA lacked an effective command structure and because of the pro-treaty forces' defensive tactics throughout the war, Michael Collins and his pro-treaty forces were able to build up an army with many tens of thousands of World War I veterans from the 1922 disbanded Irish regiments of the British Army, capable of overwhelming the anti-treatyists. British supplies of artillery, aircraft, machine-guns and ammunition boosted pro-treaty forces, and the threat of a return of Crown forces to the Free State removed any doubts about the necessity of enforcing the treaty. Lack of public support for the anti-treaty forces (often called the Irregulars) and the determination of the government to overcome the Irregulars contributed significantly to their defeat.

Constitution of Ireland 1937

Following a national plebiscite in July 1937, the new Constitution of Ireland (Bunreacht na hÉireann) came into force on 29 December 1937.[46] This replaced the Constitution of the Irish Free State and declared that the name of the state is Éire, or "Ireland" in the English language.[47] While Articles 2 and 3 of the Constitution defined the national territory to be the whole island, they also confined the state's jurisdiction to the area that had been the Irish Free State. The former Irish Free State government had abolished the Office of Governor-General in December 1936. Although the constitution established the office of President of Ireland, the question over whether Ireland was a republic remained open. Diplomats were accredited to the king, but the president exercised all internal functions of a head of state.[48] For instance, the President gave assent to new laws with his own authority, without reference to King George VI who was only an "organ", that was provided for by statute law.

Ireland remained neutral during World War II, a period it described as The Emergency.[49] Ireland's Dominion status was terminated with the passage of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948, which came into force on 18 April 1949 and declared that the state was a republic.[50][51] At the time, a declaration of a republic terminated Commonwealth membership. This rule was changed 10 days after Ireland declared itself a republic, with the London Declaration of 28 April 1949. Ireland did not reapply when the rules were altered to permit republics to join. Later, the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 was repealed in Ireland by the Statute Law Revision (Pre-Union Irish Statutes) Act 1962.[52]

Recent history

.jpg.webp)

Ireland became a member of the United Nations in December 1955, after having been denied membership because of its neutral stance during the Second World War and not supporting the Allied cause.[53] At the time, joining the UN involved a commitment to using force to deter aggression by one state against another if the UN thought it was necessary.[54]

Interest towards membership of the European Communities (EC) developed in Ireland during the 1950s, with consideration also given to membership of the European Free Trade Area. As the United Kingdom intended on EC membership, Ireland applied for membership in July 1961 due to the substantial economic linkages with the United Kingdom. However, the founding EC members remained sceptical regarding Ireland's economic capacity, neutrality, and unattractive protectionist policy.[55] Many Irish economists and politicians realised that economic policy reform was necessary. The prospect of EC membership became doubtful in 1963 when French President General Charles de Gaulle stated that France opposed Britain's accession, which ceased negotiations with all other candidate countries. However, in 1969 his successor, Georges Pompidou, was not opposed to British and Irish membership. Negotiations began and in 1972 the Treaty of Accession was signed. A referendum was held later that year which confirmed Ireland's entry into the bloc, and it finally joined the EC as a member state on 1 January 1973.[56]

The economic crisis of the late 1970s was fuelled by the Fianna Fáil government's budget, the abolition of the car tax, excessive borrowing, and global economic instability including the 1979 oil crisis.[57] There were significant policy changes from 1989 onwards, with economic reform, tax cuts, welfare reform, an increase in competition, and a ban on borrowing to fund current spending. This policy began in 1989–1992 by the Fianna Fáil/Progressive Democrat government, and continued by the subsequent Fianna Fáil/Labour government and Fine Gael/Labour/Democratic Left government. Ireland became one of the world's fastest growing economies by the late 1990s in what was known as the Celtic Tiger period, which lasted until the Great Recession. However, since 2014, Ireland has experienced increased economic activity.[58]

.jpeg.webp)

In the Northern Ireland question, the British and Irish governments started to seek a peaceful resolution to the violent conflict involving many paramilitaries and the British Army in Northern Ireland known as "The Troubles". A peace settlement for Northern Ireland, known as the Good Friday Agreement, was approved in 1998 in referendums north and south of the border. As part of the peace settlement, the territorial claim to Northern Ireland in Articles 2 and 3 of the Constitution of Ireland was removed by referendum. In its white paper on Brexit the United Kingdom government reiterated its commitment to the Good Friday Agreement. With regard to Northern Ireland's status, it said that the UK Government's "clearly-stated preference is to retain Northern Ireland’s current constitutional position: as part of the UK, but with strong links to Ireland".[59]

Geography

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1434579.jpg.webp)

The state extends over an area of about five-sixths (70,273 km2 or 27,133 sq mi) of the island of Ireland (84,421 km2 or 32,595 sq mi), with Northern Ireland constituting the remainder. The island is bounded to the north and west by the Atlantic Ocean and to the northeast by the North Channel. To the east, the Irish Sea connects to the Atlantic Ocean via St George's Channel and the Celtic Sea to the southwest.

The western landscape mostly consists of rugged cliffs, hills and mountains. The central lowlands are extensively covered with glacial deposits of clay and sand, as well as significant areas of bogland and several lakes. The highest point is Carrauntoohil (1,038.6 m or 3,407 ft), located in the MacGillycuddy's Reeks mountain range in the southwest. River Shannon, which traverses the central lowlands, is the longest river in Ireland at 386 kilometres or 240 miles in length. The west coast is more rugged than the east, with numerous islands, peninsulas, headlands and bays.

Ireland is one of the least forested countries in Europe.[60] Until the end of the Middle Ages, the land was heavily forested. Native species include deciduous trees such as oak, ash, hazel, birch, alder, willow, aspen, elm, rowan and hawthorn, as well as evergreen trees such Scots pine, yew, holly and strawberry trees.[61] The growth of blanket bog and the extensive clearing of woodland for farming are believed to be the main causes of deforestation.[62] Today, only about 10% of Ireland is woodland,[63] most of which is non-native conifer plantations, and only 2% of which is native woodland.[64][65] The average woodland cover in European countries is over 33%.[63] According to Coillte, a state-owned forestry business, the country's climate gives Ireland one of the fastest growth rates for forests in Europe.[66] Hedgerows, which are traditionally used to define land boundaries, are an important substitute for woodland habitat, providing refuge for native wild flora and a wide range of insect, bird and mammal species.[67] It is home to two terrestrial ecoregions: Celtic broadleaf forests and North Atlantic moist mixed forests.[68]

Agriculture accounts for about 64% of the total land area.[69] This has resulted in limited land to preserve natural habitats, in particular for larger wild mammals with greater territorial requirements.[70] The long history of agricultural production coupled with modern agricultural methods, such as pesticide and fertiliser use, has placed pressure on biodiversity.[71]

Climate

.jpg.webp)

The Atlantic Ocean and the warming influence of the Gulf Stream affect weather patterns in Ireland.[72] Temperatures differ regionally, with central and eastern areas tending to be more extreme. However, due to a temperate oceanic climate, temperatures are seldom lower than −5 °C (23 °F) in winter or higher than 26 °C (79 °F) in summer.[73] The highest temperature recorded in Ireland was 33.3 °C (91.9 °F) on 26 June 1887 at Kilkenny Castle in Kilkenny, while the lowest temperature recorded was −19.1 °C (−2.4 °F) at Markree Castle in Sligo.[74] Rainfall is more prevalent during winter months and less so during the early months of summer. Southwestern areas experience the most rainfall as a result of south westerly winds, while Dublin receives the least. Sunshine duration is highest in the southeast of the country.[72] The far north and west are two of the windiest regions in Europe, with great potential for wind energy generation.[75]

Ireland normally gets between 1100 and 1600 hours of sunshine each year, most areas averaging between 3.25 and 3.75 hours a day. The sunniest months are May and June, which average between 5 and 6.5 hours per day over most of the country. The extreme southeast gets most sunshine, averaging over 7 hours a day in early summer. December is the dullest month, with an average daily sunshine ranging from about 1 hour in the north to almost 2 hours in the extreme southeast. The sunniest summer in the 100 years from 1881 to 1980 was 1887, according to measurements made at the Phoenix Park in Dublin; 1980 was the dullest.[76]

Politics

Ireland is a constitutional republic with a parliamentary system of government. The Oireachtas is the bicameral national parliament composed of the President of Ireland and the two Houses of the Oireachtas: Dáil Éireann (House of Representatives) and Seanad Éireann (Senate).[77] Áras an Uachtaráin is the official residence of the President of Ireland, while the houses of the Oireachtas meet at Leinster House in Dublin.

The President serves as head of state, is elected for a seven-year term, and may be re-elected once. The President is primarily a figurehead, but is entrusted with certain constitutional powers with the advice of the Council of State. The office has absolute discretion in some areas, such as referring a bill to the Supreme Court for a judgment on its constitutionality.[78] Michael D. Higgins became the ninth President of Ireland on 11 November 2011.[79]

The Taoiseach (Prime Minister) serves as the head of government and is appointed by the President upon the nomination of the Dáil. Most Taoisigh have served as the leader of the political party that gains the most seats in national elections. It has become customary for coalitions to form a government, as there has not been a single-party government since 1989.[80] Micheál Martin succeeded Leo Varadkar as Taoiseach on 27 June 2020, after forming a historic coalition between his Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael of Leo Varadkar.[81]

The Dáil has 160 members (Teachtaí Dála) elected to represent multi-seat constituencies under the system of proportional representation and by means of the single transferable vote. The Seanad is composed of sixty members, with eleven nominated by the Taoiseach, six elected by two universities, and 43 elected by public representatives from panels of candidates established on a vocational basis.

The Government is constitutionally limited to fifteen members. No more than two members can be selected from the Seanad, and the Taoiseach, Tánaiste (Deputy Prime Minister) and Minister for Finance must be members of the Dáil. The Dáil must be dissolved within five years after its first meeting following the previous election,[82] and a general election for members of the Dáil must take place no later than thirty days after the dissolution. In accordance with the Constitution of Ireland, parliamentary elections must be held at least every seven years, though a lower limit may be set by statute law. The current government is a coalition of Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, and the Green Party with Micheál Martin as Taoiseach and Leo Varadkar as Tánaiste. Opposition parties in the current Dáil are Sinn Féin, the Labour Party, Solidarity–People Before Profit, Social Democrats, Aontú, as well as a number of independents.

Ireland has been a member state of the European Union since 1973. Citizens of the United Kingdom can freely enter the country without a passport due to the Common Travel Area, which is a passport-free zone comprising the islands of Ireland, Great Britain, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. However, some identification is required at airports and seaports.

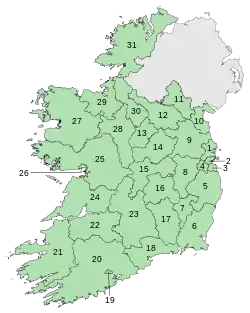

Local government

The Local Government Act 1898 was the founding statute of the present system of local government, while the Twentieth Amendment to the constitution of 1999 provided for its constitutional recognition. The twenty-six traditional counties of Ireland are the basis of the local government areas, with the traditional counties of Cork, Dublin and Galway containing two or more local government areas. The Local Government Act 2001, as amended by the Local Government Reform Act 2014,[83] provides for a system of thirty-one local authorities – twenty-six county councils, two city and county councils and three city councils.[83] Counties (with the exception of the counties in Dublin and the three city councils) are divided into municipal districts. A second local government tier of town councils was abolished in 2014.

|

Local authorities are responsible for matters such as planning, local roads, sanitation, and libraries. The breaching of county boundaries should be avoided as far as practicable in drawing Dáil constituencies. Counties with greater populations have multiple constituencies, some of more than one county, but generally do not cross county boundaries. The counties are grouped into three regions, each with a Regional Assembly composed of members delegated by the various county and city councils in the region. The regions do not have any direct administrative role as such, but they serve for planning, coordination and statistical purposes.

Law

Ireland has a common law legal system with a written constitution that provides for a parliamentary democracy. The court system consists of the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, the High Court, the Circuit Court and the District Court, all of which apply the Irish law and hear both civil and criminal matters. Trials for serious offences must usually be held before a jury. The High Court, Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court have authority, by means of judicial review, to determine the compatibility of laws and activities of other institutions of the state with the constitution and the law. Except in exceptional circumstances, court hearings must occur in public.[84][85]

Garda Síochána na hÉireann (Guardians of the Peace of Ireland), more commonly referred to as the Gardaí, is the state's civilian police force. The force is responsible for all aspects of civil policing, both in terms of territory and infrastructure. It is headed by the Garda Commissioner, who is appointed by the Government. Most uniformed members do not routinely carry firearms. Standard policing is traditionally carried out by uniformed officers equipped only with a baton and pepper spray.[86]

The Military Police is the corps of the Irish Army responsible for the provision of policing service personnel and providing a military police presence to forces while on exercise and deployment. In wartime, additional tasks include the provision of a traffic control organisation to allow rapid movement of military formations to their mission areas. Other wartime roles include control of prisoners of war and refugees.[87]

Ireland's citizenship laws relate to "the island of Ireland", including islands and seas, thereby extending them to Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom. Therefore, anyone born in Northern Ireland who meets the requirements for being an Irish citizen, such as birth on the island of Ireland to an Irish or British citizen parent or a parent who is entitled to live in Northern Ireland or the Republic without restriction on their residency,[88] may exercise an entitlement to Irish citizenship, such as an Irish passport.[89]

Foreign relations

Foreign relations are substantially influenced by membership of the European Union, although bilateral relations with the United Kingdom and United States are also important.[90] It held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union on six occasions, most recently from January to June 2013.[91]

.jpg.webp)

Ireland tends towards independence in foreign policy; thus the country is not a member of NATO and has a longstanding policy of military neutrality. This policy has led to the Irish Defence Forces contributing to peace-keeping missions with the United Nations since 1960, including during the Congo Crisis and subsequently in Cyprus, Lebanon and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[92]

Despite Irish neutrality during World War II, Ireland had more than 50,000 participants in the war through enlistment in the British armed forces. During the Cold War, Irish military policy, while ostensibly neutral, was biased towards NATO.[93] During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Seán Lemass authorised the search of Cuban and Czechoslovak aircraft passing through Shannon and passed the information to the CIA.[94] Ireland's air facilities were used by the United States military for the delivery of military personnel involved in the 2003 invasion of Iraq through Shannon Airport. The airport had previously been used for the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, as well as the First Gulf War.[95]

Since 1999, Ireland has been a member of NATO's Partnership for Peace (PfP) program and NATO's Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC), which is aimed at creating trust between NATO and other states in Europe and the former Soviet Union.[96][97]

Military

Ireland is a neutral country,[98] and has "triple-lock" rules governing the participation of Irish troops in conflict zones, whereby approval must be given by the UN, the Dáil and Government.[99] Accordingly, its military role is limited to national self-defence and participation in United Nations peacekeeping.

.jpg.webp)

The Irish Defence Forces (Óglaigh na hÉireann) are made up of the Army, Naval Service, Air Corps and Reserve Defence Force. It is small but well equipped, with almost 10,000 full-time military personnel and over 2,000 in reserve.[100][101] Daily deployments of the Defence Forces cover aid to civil power operations, protection and patrol of Irish territorial waters and EEZ by the Irish Naval Service, and UN, EU and PfP peace-keeping missions. By 1996, over 40,000 Irish service personnel had served in international UN peacekeeping missions.[102]

The Irish Air Corps is the air component of the Defence Forces and operates sixteen fixed wing aircraft and eight helicopters. The Irish Naval Service is Ireland's navy, and operates six patrol ships, and smaller numbers of inflatable boats and training vessels, and has armed boarding parties capable of seizing a ship and a special unit of frogmen. The military includes the Reserve Defence Forces (Army Reserve and Naval Service Reserve) for part-time reservists. Ireland's special forces include the Army Ranger Wing, which trains and operates with international special operations units. The President is the formal Supreme Commander of the Defence Forces, but in practice these Forces answer to the Government via the Minister for Defence.[103]

In 2017, Ireland signed the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[104]

Economy

Ireland is an open economy (6th on the Index of Economic Freedom), and ranks first for "high-value" foreign direct investment (FDI) flows.[105] Using the metric global GDP per capita, Ireland ranks 5th of 187 (IMF) and 6th of 175 (World Bank). The alternative metric modified Gross National Income (GNI) is intended to give a more accurate view of "activity in the domestic economy".[106] This is particularly relevant in Ireland's small globalised economy, as GDP includes income from non-Irish owned companies, which flows out of Ireland.[107] Indeed, foreign multinationals are the driver of Ireland's economy, employing a quarter of the private sector workforce,[108] and paying 80% of Irish business taxes.[109][110][111] 14 of Ireland's top 20 firms (by 2017 turnover) are US-based multinationals[112] (80% of foreign multinationals in Ireland are from the US;[113][114] there are no non-US/non-UK foreign firms in Ireland's top 50 firms by turnover, and only one by employees, that being German retailer Lidl at No. 41[112]).

.svg.png.webp)

Ireland adopted the euro currency in 2002 along with eleven other EU member states.[71]

The country officially exited recession in 2010, assisted by a growth in exports from US multinationals in Ireland.[115] However, due to a rise in the cost of public borrowing due to government guarantees of private banking debt, the Irish government accepted an €85 billion programme of assistance from the EU, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and bilateral loans from the United Kingdom, Sweden and Denmark.[116] Following three years of contraction, the economy grew by 0.7% in 2011 and 0.9% in 2012.[117] The unemployment rate was 14.7% in 2012, including 18.5% among recent immigrants.[118] In March 2016 the unemployment rate was reported by the CSO to be 8.6%, down from a peak unemployment rate of 15.1% in February 2012.[119] In addition to unemployment, net emigration from Ireland between 2008 and 2013 totalled 120,100,[120] or some 2.6% of the total population according to the Census of Ireland 2011. One-third of the emigrants were aged between 15 and 24.[120]

Ireland exited its EU-IMF bailout programme on 15 December 2013.[121] Having implemented budget cuts, reforms and sold assets, Ireland was again able to access debt markets. Since then, Ireland has been able to sell long term bonds at record rates.[122] However, the stabilisation of the Irish credit bubble required a large transfer of debt from the private sector balance sheet (highest OECD leverage), to the public sector balance sheet (almost unleveraged, pre-crisis), via Irish bank bailouts and public deficit spending.[123][124] The transfer of this debt means that Ireland, in 2017, still has one of the highest levels of both public sector indebtedness, and private sector indebtedness, in the EU-28/OECD.[125][126][127][128][129][130]

Ireland continues to de-leverage its domestic private sector while growing its US multinational-driven economy. Ireland became the main destination for US corporate tax inversions from 2009 to 2016 (mostly pharmaceutical), peaking with the blocked $160bn Allergan/Pfizer inversion (world's largest inversion, and circa 85% of Irish GNI*).[131][132] Ireland also became the largest foreign location for US "big cap" technology multinationals (i.e. Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook), which delivered a GDP growth rate of 26.3% (and GNP growth rate of 18.7%) in 2015. This growth was subsequently shown to be due to Apple restructuring its "double Irish" subsidiary (Apple Sales International, currently under threat of a €13bn EU "illegal state aid" fine for preferential tax treatment).

Taxation policy

Ireland's economy was transformed with the creation of a 10% low-tax "special economic zone", called the International Financial Services Centre (or "IFSC"), in 1987.[133] In 1999, the entire country was effectively "turned into an IFSC" with the reduction of Irish corporation tax from 32% to 12.5% (the birth of Ireland's "low-tax" model).[134][135] This accelerated Ireland's transition from a predominantly agricultural economy into a knowledge economy focused on attracting US multinationals from high-tech, life sciences, and financial services industries seeking to avail of Ireland's attractive corporate tax rates and unique corporate tax system.

The "multinational tax schemes" foreign firms use in Ireland materially distort Irish economic statistics. This reached a climax with the famous "leprechaun economics" GDP/GNP growth rates of 2015 (as Apple restructured its Irish subsidiaries in 2015). The Central Bank of Ireland introduced a new statistic, "modified GNI" (or GNI*), to remove these distortions. GNI* is 30% below GDP (or, GDP is 143% of GNI).[17][18] As such, Ireland's GDP and GNP should no longer be used.[136][137][138]

From the creation of the IFSC, the country experienced strong and sustained economic growth which fuelled a dramatic rise in Irish consumer borrowing and spending, and Irish construction and investment, which became known as the Celtic Tiger period.[139][140] By 2007, Ireland had the highest private sector debt in the OECD with a household debt-to-disposable income ratio of 190%. Global capital markets, who had financed Ireland's build-up of debt in the Celtic Tiger period by enabling Irish banks to borrow in excess of the domestic deposit base (to over 180% at peak[141]), withdrew support in the financial crisis of 2007–2008. Their withdrawal from the over-borrowed Irish credit system would precipitate a deep Irish property correction which then led to the Post-2008 Irish banking crisis.[142][139]

Ireland's successful "low-tax" economy opens it to accusations of being a "corporate tax haven",[143][144][145] and led to it being "blacklisted" by Brazil.[146][147] A 2017 study ranks Ireland as the 5th largest global Conduit OFC (conduits legally route funds to tax havens). A serious challenge is the passing of the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (whose FDII and GILTI regimes target Ireland's "multinational tax schemes").[148][149][150][151] The EU's 2018 Digital Sales Tax (DST)[152] (and desire for a CCCTB[153]) is also seen as an attempt to restrict Irish "multinational tax schemes" by US technology firms.[154][155][156]

Trade

.jpg.webp)

Although multinational corporations dominate Ireland's export sector, exports from other sources also contribute significantly to the national income. The activities of multinational companies based in Ireland have made it one of the largest exporters of pharmaceutical agents, medical devices and software-related goods and services in the world. Ireland's exports also relate to the activities of large Irish companies (such as Ryanair, Kerry Group and Smurfit Kappa) and exports of mineral resources: Ireland is the seventh largest producer of zinc concentrates, and the twelfth largest producer of lead concentrates. The country also has significant deposits of gypsum, limestone, and smaller quantities of copper, silver, gold, barite, and dolomite.[71] Tourism in Ireland contributes about 4% of GDP and is a significant source of employment.

Other goods exports include agri-food, cattle, beef, dairy products, and aluminum. Ireland's major imports include data processing equipment, chemicals, petroleum and petroleum products, textiles, and clothing. Financial services provided by multinational corporations based at the Irish Financial Services Centre also contribute to Irish exports. The difference between exports (€89.4 billion) and imports (€45.5 billion) resulted an annual trade surplus of €43.9 billion in 2010,[157] which is the highest trade surplus relative to GDP achieved by any EU member state.

The EU is by far the country's largest trading partner, accounting for 57.9% of exports and 60.7% of imports. The United Kingdom is the most important trading partner within the EU, accounting for 15.4% of exports and 32.1% of imports. Outside the EU, the United States accounted for 23.2% of exports and 14.1% of imports in 2010.[157]

Energy

ESB, Bord Gáis Energy and Airtricity are the three main electricity and gas suppliers in Ireland. There are 19.82 billion cubic metres of proven reserves of gas.[71][158] Natural gas extraction previously occurred at the Kinsale Head until its exhaustion. The Corrib gas field was due to come on stream in 2013/14. In 2012, the Barryroe field was confirmed to have up to 1.6 billion barrels of oil in reserve, with between 160 and 600 million recoverable.[159] That could provide for Ireland's entire energy needs for up to 13 years, when it is developed in 2015/16. There have been significant efforts to increase the use of renewable and sustainable forms of energy in Ireland, particularly in wind power, with 3,000 MegaWatts[160] of wind farms being constructed, some for the purpose of export.[161] The Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) has estimated that 6.5% of Ireland's 2011 energy requirements were produced by renewable sources.[162] The SEAI has also reported an increase in energy efficiency in Ireland with a 28% reduction in carbon emissions per house from 2005 to 2013.[163]

Transport

The country's three main international airports at Dublin, Shannon and Cork serve many European and intercontinental routes with scheduled and chartered flights. The London to Dublin air route is the ninth busiest international air route in the world, and also the busiest international air route in Europe, with 14,500 flights between the two in 2017.[164][165] In 2015, 4.5 million people took the route, at that time, the world's second-busiest.[164] Aer Lingus is the flag carrier of Ireland, although Ryanair is the country's largest airline. Ryanair is Europe's largest low-cost carrier,[166] the second largest in terms of passenger numbers, and the world's largest in terms of international passenger numbers.[167]

Railway services are provided by Iarnród Éireann (Irish Rail), which operates all internal intercity, commuter and freight railway services in the country. Dublin is the centre of the network with two main stations, Heuston station and Connolly station, linking to the country's cities and main towns. The Enterprise service, which runs jointly with Northern Ireland Railways, connects Dublin and Belfast. The whole of Ireland's mainline network operates on track with a gauge of 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm), which is unique in Europe and has resulted in distinct rolling stock designs. Dublin's public transport network includes the DART, Luas, Dublin Bus, and dublinbikes.[168]

Motorways, national primary roads and national secondary roads are managed by Transport Infrastructure Ireland, while regional roads and local roads are managed by the local authorities in each of their respective areas. The road network is primarily focused on the capital, but motorways connect it to other major Irish cities including Cork, Limerick, Waterford and Galway.[169]

Dublin is served by major infrastructure such as the East-Link and West-Link toll-bridges, as well as the Dublin Port Tunnel. The Jack Lynch Tunnel, under the River Lee in Cork, and the Limerick Tunnel, under the River Shannon, were two major projects outside Dublin.[170]

Demographics

Genetic research suggests that the earliest settlers migrated from Iberia following the most recent ice age.[171] After the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age, migrants introduced a Celtic language and culture. Migrants from the two latter eras still represent the genetic heritage of most Irish people.[172][173] Gaelic tradition expanded and became the dominant form over time. Irish people are a combination of Gaelic, Norse, Anglo-Norman, French, and British ancestry.

The population of Ireland stood at 4,761,865 in 2016, an increase of 12.3% since 2006.[174] As of 2011, Ireland had the highest birth rate in the European Union (16 births per 1,000 of population).[175] In 2014, 36.3% of births were to unmarried women.[176] Annual population growth rates exceeded 2% during the 2002–2006 intercensal period, which was attributed to high rates of natural increase and immigration.[177] This rate declined somewhat during the subsequent 2006–2011 intercensal period, with an average annual percentage change of 1.6%. The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2017 was estimated at 1.80 children born per woman, below the replacement rate of 2.1, it remains considerably below the high of 4.2 children born per woman in 1850.[178] In 2018 the median age of the Irish population was 37.1 years.[179]

At the time of the 2016 census, the number of non-Irish nationals was recorded at 535,475. This represents a 2% decrease from the 2011 census figure of 544,357. The five largest sources of non-Irish nationals were Poland (122,515), the UK (103,113), Lithuania (36,552), Romania (29,186) and Latvia (19,933) respectively. Compared with 2011, the number of UK, Polish, Lithuanian and Latvian nationals fell. There were four new additions to the top ten largest non-Irish nationalities in 2016: Brazilian (13,640), Spanish (12,112), Italian (11,732), and French (11,661).[180]

| Largest urban centres by population (2016 census) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Settlement | Population | # | Settlement | Population | ||

| 1 | Dublin | 1,173,179[181] | 11 | Kilkenny | 26,512 | ||

| 2 | Cork | 208,669[182] | 12 | Ennis | 25,276 | ||

| 3 | Limerick | 94,192[183] | 13 | Carlow | 24,272 | ||

| 4 | Galway | 79,934[184] | 14 | Tralee | 23,691 | ||

| 5 | Waterford | 53,504[185] | 15 | Newbridge | 22,742 | ||

| 6 | Drogheda | 40,956[186] | 16 | Portlaoise | 22,050 | ||

| 7 | Swords | 39,248[187] | 17 | Balbriggan | 21,722 | ||

| 8 | Dundalk | 39,004[188] | 18 | Naas | 21,393 | ||

| 9 | Bray | 32,600[189] | 19 | Athlone | 21,349 | ||

| 10 | Navan | 30,173[190] | 20 | Mullingar | 20,928 | ||

Functional urban areas

The following is a list of functional urban areas in Ireland (as defined by the OECD) and their approximate populations as of 2015.[191]

| Functional urban areas | Approx. population 2015 |

|---|---|

| Dublin | 1,830,000 |

| Cork | 410,000 |

| Galway | 180,000 |

| Limerick | 160,000 |

| Waterford | 100,000 |

Languages

The Irish Constitution describes Irish as the "national language" and the "first official language", but English (the "second official language") is the dominant language. In the 2016 census, about 1.75 million people (40% of the population) said they were able to speak Irish but, of those, under 74,000 spoke it on a daily basis.[192] Irish is spoken as a community language only in a small number of rural areas mostly in the west and south of the country, collectively known as the Gaeltacht. Except in Gaeltacht regions, road signs are usually bilingual.[193] Most public notices and print media are in English only. While the state is officially bilingual, citizens can often struggle to access state services in Irish and most government publications are not available in both languages, even though citizens have the right to deal with the state in Irish. Irish language media include the TV channel TG4, the radio station RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta and online newspaper Tuairisc.ie. In the Irish Defence Forces, all foot and arms drill commands are given in the Irish language.

As a result of immigration, Polish is the most widely spoken language in Ireland after English, with Irish as the third most spoken.[194] Several other Central European languages (namely Czech, Hungarian and Slovak), as well as Baltic languages (Lithuanian and Latvian) are also spoken on a day-to-day basis. Other languages spoken in Ireland include Shelta, spoken by Irish Travellers, and a dialect of Scots is spoken by some Ulster Scots people in Donegal.[195] Most secondary school students choose to learn one or two foreign languages. Languages available for the Junior Certificate and the Leaving Certificate include French, German, Italian and Spanish; Leaving Certificate students can also study Arabic, Japanese and Russian. Some secondary schools also offer Ancient Greek, Hebrew and Latin. The study of Irish is generally compulsory for Leaving Certificate students, but some may qualify for an exemption in some circumstances, such as learning difficulties or entering the country after age 11.[196]

Healthcare

Healthcare in Ireland is provided by both public and private healthcare providers.[197] The Minister for Health has responsibility for setting overall health service policy. Every resident of Ireland is entitled to receive health care through the public health care system, which is managed by the Health Service Executive and funded by general taxation. A person may be required to pay a subsidised fee for certain health care received; this depends on income, age, illness or disability. All maternity services are provided free of charge and children up to the age of 6 months. Emergency care is provided to patients who present to a hospital emergency department. However, visitors to emergency departments in non-emergency situations who are not referred by their GP may incur a fee of €100. In some circumstances this fee is not payable or may be waived.[198]

Anyone holding a European Health Insurance Card is entitled to free maintenance and treatment in public beds in Health Service Executive and voluntary hospitals. Outpatient services are also provided for free. However, the majority of patients on median incomes or above are required to pay subsidised hospital charges. Private health insurance is available to the population for those who want to avail of it.

The average life expectancy in Ireland in 2016 was 81.8 years (OECD 2016 list), with 79.9 years for men and 83.6 years for women.[199] It has the highest birth rate in the EU (16.8 births per 1,000 inhabitants, compared to an EU average of 10.7)[200] and a very low infant mortality rate (3.5 per 1,000 live births). The Irish healthcare system ranked 13th out of 34 European countries in 2012 according to the European Health Consumer Index produced by Health Consumer Powerhouse.[201] The same report ranked the Irish healthcare system as having the 8th best health outcomes but only the 21st most accessible system in Europe.

Education

Ireland has three levels of education: primary, secondary and higher education. The education systems are largely under the direction of the Government via the Minister for Education. Recognised primary and secondary schools must adhere to the curriculum established by the relevant authorities. Education is compulsory between the ages of six and fifteen years, and all children up to the age of eighteen must complete the first three years of secondary, including one sitting of the Junior Certificate examination.[202]

There are approximately 3,300 primary schools in Ireland.[203] The vast majority (92%) are under the patronage of the Catholic Church. Schools run by religious organisations, but receiving public money and recognition, cannot discriminate against pupils based upon religion or lack thereof. A sanctioned system of preference does exist, where students of a particular religion may be accepted before those who do not share the ethos of the school, in a case where a school's quota has already been reached.

The Leaving Certificate, which is taken after two years of study, is the final examination in the secondary school system. Those intending to pursue higher education normally take this examination, with access to third-level courses generally depending on results obtained from the best six subjects taken, on a competitive basis.[204] Third-level education awards are conferred by at least 38 Higher Education Institutions – this includes the constituent or linked colleges of seven universities, plus other designated institutions of the Higher Education and Training Awards Council.

The Programme for International Student Assessment, coordinated by the OECD, currently ranks Ireland as having the fourth highest reading score, ninth highest science score and thirteenth highest mathematics score, among OECD countries, in its 2012 assessment.[205] In 2012, Irish students aged 15 years had the second highest levels of reading literacy in the EU.[206] Ireland also has 0.747 of the World's top 500 Universities per capita, which ranks the country in 8th place in the world.[207] Primary, secondary and higher (university/college) level education are all free in Ireland for all EU citizens.[208] There are charges to cover student services and examinations.

In addition, 37 percent of Ireland's population has a university or college degree, which is among the highest percentages in the world.[209][210]

Religion

Religious freedom is constitutionally provided for in Ireland, and the country's constitution has been secular since 1973. Christianity is the predominant religion, and while Ireland remains a predominantly Catholic country, the percentage of the population who identified as Catholic on the census has fallen sharply from 84.2 percent in the 2011 census to 78.3 percent in the most recent 2016 census. Other results from the 2016 census are: 4.2% Protestant, 1.3% Orthodox, 1.3% as Muslim, and 9.8% as having no religion.[211] According to a Georgetown University study, before 2000 the country had one of the highest rates of regular mass attendance in the Western world.[212] While daily attendance was 13% in 2006, there was a reduction in weekly attendance from 81% in 1990 to 48% in 2006, although the decline was reported as stabilising.[213] In 2011, it was reported that weekly Mass attendance in Dublin was just 18%, and was even lower among younger generations.[214]

The Church of Ireland, at 2.7% of the population, is the second largest Christian denomination. Membership declined throughout the twentieth century, but experienced an increase early in the 21st century, as have other small Christian denominations. Other significant Protestant denominations are the Presbyterian Church and Methodist Church. Immigration has contributed to a growth in Hindu and Muslim populations. In percentage terms, Orthodox Christianity and Islam were the fastest growing religions, with increases of 100% and 70% respectively.[215]

Ireland's patron saints are Saint Patrick, Saint Bridget and Saint Columba, with Saint Patrick commonly recognised as the patron saint. Saint Patrick's Day is celebrated on 17 March in Ireland and abroad as the Irish national day, with parades and other celebrations.

As with other predominantly Catholic European states, Ireland underwent a period of legal secularisation in the late twentieth century. In 1972, the article of the Constitution naming specific religious groups was deleted by the Fifth Amendment in a referendum. Article 44 remains in the Constitution: "The State acknowledges that the homage of public worship is due to Almighty God. It shall hold His Name in reverence, and shall respect and honour religion." The article also establishes freedom of religion, prohibits endowment of any religion, prohibits the state from religious discrimination, and requires the state to treat religious and non-religious schools in a non-prejudicial manner.

Religious studies was introduced as an optional Junior Certificate subject in 2001. Although most schools are run by religious organisations, a secularist trend is occurring among younger generations.[216]

Culture

Ireland's culture was for centuries predominantly Gaelic, and it remains one of the six principal Celtic nations. Following the Anglo-Norman invasion in the 12th century, and gradual British conquest and colonisation beginning in the 16th century, Ireland became influenced by English and Scottish culture. Subsequently, Irish culture, though distinct in many aspects, shares characteristics with the Anglosphere, Catholic Europe, and other Celtic regions. The Irish diaspora, one of the world's largest and most dispersed, has contributed to the globalisation of Irish culture, producing many prominent figures in art, music, and science.

Literature

Ireland has made a significant contribution to world literature in both the English and Irish languages. Modern Irish fiction began with the publishing of the 1726 novel Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift. Other writers of importance during the 18th century and their most notable works include Laurence Sterne with the publication of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman and Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield. Numerous Irish novelists emerged during the 19th century, including Maria Edgeworth, John Banim, Gerald Griffin, Charles Kickham, William Carleton, George Moore, and Somerville and Ross. Bram Stoker is best known as the author of the 1897 novel Dracula.

James Joyce (1882–1941) published his most famous work Ulysses in 1922, which is an interpretation of the Odyssey set in Dublin. Edith Somerville continued writing after the death of her partner Martin Ross in 1915. Dublin's Annie M. P. Smithson was one of several authors catering for fans of romantic fiction in the 1920s and 1930s. After the Second World War, popular novels were published by, among others, Brian O'Nolan, who published as Flann O'Brien, Elizabeth Bowen, and Kate O'Brien. During the final decades of the 20th century, Edna O'Brien, John McGahern, Maeve Binchy, Joseph O'Connor, Roddy Doyle, Colm Tóibín, and John Banville came to the fore as novelists.

Patricia Lynch was a prolific children's author in the 20th century, while Eoin Colfer's works were NYT Best Sellers in this genre in the early 21st century.[217] In the genre of the short story, which is a form favoured by many Irish writers, the most prominent figures include Seán Ó Faoláin, Frank O'Connor and William Trevor. Well known Irish poets include Patrick Kavanagh, Thomas McCarthy, Dermot Bolger, and Nobel Prize in Literature laureates William Butler Yeats and Seamus Heaney (born in Northern Ireland but resided in Dublin). Prominent writers in the Irish language are Pádraic Ó Conaire, Máirtín Ó Cadhain, Séamus Ó Grianna, and Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill.

The history of Irish theatre begins with the expansion of the English administration in Dublin during the early 17th century, and since then, Ireland has significantly contributed to English drama. In its early history, theatrical productions in Ireland tended to serve political purposes, but as more theatres opened and the popular audience grew, a more diverse range of entertainments were staged. Many Dublin-based theatres developed links with their London equivalents, and British productions frequently found their way to the Irish stage. However, most Irish playwrights went abroad to establish themselves. In the 18th century, Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan were two of the most successful playwrights on the London stage at that time. At the beginning of the 20th century, theatre companies dedicated to the staging of Irish plays and the development of writers, directors and performers began to emerge, which allowed many Irish playwrights to learn their trade and establish their reputations in Ireland rather than in Britain or the United States. Following in the tradition of acclaimed practitioners, principally Oscar Wilde, Literature Nobel Prize laureates George Bernard Shaw (1925) and Samuel Beckett (1969), playwrights such as Seán O'Casey, Brian Friel, Sebastian Barry, Brendan Behan, Conor McPherson and Billy Roche have gained popular success.[218] Other Irish playwrights of the 20th century include Denis Johnston, Thomas Kilroy, Tom Murphy, Hugh Leonard, Frank McGuinness, and John B. Keane.

Music and dance

Irish traditional music has remained vibrant, despite globalising cultural forces, and retains many traditional aspects. It has influenced various music genres, such as American country and roots music, and to some extent modern rock. It has occasionally been blended with styles such as rock and roll and punk rock. Ireland has also produced many internationally known artists in other genres, such as rock, pop, jazz, and blues. Ireland's best selling musical act is the rock band U2, who have sold 170 million copies of their albums worldwide since their formation in 1976.[219]

There are a number of classical music ensembles around the country, such as the RTÉ Performing Groups.[220] Ireland also has two opera organisations: Irish National Opera in Dublin, and the annual Wexford Opera Festival, which promotes lesser-known operas, takes place during October and November.

Ireland has participated in the Eurovision Song Contest since 1965.[221] Its first win was in 1970, when Dana won with All Kinds of Everything.[222] It has subsequently won the competition six more times,[223][224] the highest number of wins by any competing country. The phenomenon Riverdance originated as an interval performance during the 1994 contest.[225]

Irish dance can broadly be divided into social dance and performance dance. Irish social dance can be divided into céilí and set dancing. Irish set dances are quadrilles, danced by 4 couples arranged in a square, while céilí dances are danced by varied formations of couples of 2 to 16 people. There are also many stylistic differences between these two forms. Irish social dance is a living tradition, and variations in particular dances are found across the country. In some places dances are deliberately modified and new dances are choreographed. Performance dance is traditionally referred to as stepdance. Irish stepdance, popularised by the show Riverdance, is notable for its rapid leg movements, with the body and arms being kept largely stationary. The solo stepdance is generally characterised by a controlled but not rigid upper body, straight arms, and quick, precise movements of the feet. The solo dances can either be in "soft shoe" or "hard shoe".

Architecture

Ireland has a wealth of structures,[226] surviving in various states of preservation, from the Neolithic period, such as Brú na Bóinne, Poulnabrone dolmen, Castlestrange stone, Turoe stone, and Drombeg stone circle.[227] As Ireland was never a part of the Roman Empire, ancient architecture in Greco-Roman style is extremely rare, in contrast to most of Western Europe. The country instead had an extended period of Iron Age architecture.[228] The Irish round tower originated during the Early Medieval period.

Christianity introduced simple monastic houses, such as Clonmacnoise, Skellig Michael and Scattery Island. A stylistic similarity has been remarked between these double monasteries and those of the Copts of Egypt.[229] Gaelic kings and aristocrats occupied ringforts or crannógs.[230] Church reforms during the 12th century via the Cistercians stimulated continental influence, with the Romanesque styled Mellifont, Boyle and Tintern abbeys.[231] Gaelic settlement had been limited to the Monastic proto-towns, such as Kells, where the current street pattern preserves the original circular settlement outline to some extent.[232] Significant urban settlements only developed following the period of Viking invasions.[230] The major Hiberno-Norse Longphorts were located on the coast, but with minor inland fluvial settlements, such as the eponymous Longford.

Castles were built by the Anglo-Normans during the late 12th century, such as Dublin Castle and Kilkenny Castle,[233] and the concept of the planned walled trading town was introduced, which gained legal status and several rights by grant of a Charter under Feudalism. These charters specifically governed the design of these towns.[234] Two significant waves of planned town formation followed, the first being the 16th- and 17th-century plantation towns, which were used as a mechanism for the Tudor English kings to suppress local insurgency, followed by 18th-century landlord towns.[235] Surviving Norman founded planned towns include Drogheda and Youghal; plantation towns include Portlaoise and Portarlington; well-preserved 18th-century planned towns include Westport and Ballinasloe. These episodes of planned settlement account for the majority of present-day towns throughout the country.

Gothic cathedrals, such as St Patrick's, were also introduced by the Normans.[236] Franciscans were dominant in directing the abbeys by the Late Middle Ages, while elegant tower houses, such as Bunratty Castle, were built by the Gaelic and Norman aristocracy.[237] Many religious buildings were ruined with the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[238] Following the Restoration, palladianism and rococo, particularly country houses, swept through Ireland under the initiative of Edward Lovett Pearce, with the Houses of Parliament being the most significant.[239]

With the erection of buildings such as The Custom House, Four Courts, General Post Office and King's Inns, the neoclassical and Georgian styles flourished, especially in Dublin.[239] Georgian townhouses produced streets of singular distinction, particularly in Dublin, Limerick and Cork. Following Catholic Emancipation, cathedrals and churches influenced by the French Gothic Revival emerged, such as St Colman's and St Finbarre's.[239] Ireland has long been associated with thatched roof cottages, though these are nowadays considered quaint.[240]

Beginning with the American designed art deco church at Turner's Cross, Cork in 1927, Irish architecture followed the international trend towards modern and sleek building styles since the 20th century.[241] Other developments include the regeneration of Ballymun and an urban extension of Dublin at Adamstown.[242] Since the establishment of the Dublin Docklands Development Authority in 1997, the Dublin Docklands area underwent large-scale redevelopment, which included the construction of the Convention Centre Dublin and Grand Canal Theatre.[243] Completed in 2018, Capital Dock in Dublin is the tallest building in the Republic of Ireland achieving 79 metres (259 feet) in height (the Obel Tower in Belfast, Northern Ireland being the tallest in Ireland). The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland regulates the practice of architecture in the state.[244]

Media

Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) is Ireland's public service broadcaster, funded by a television licence fee and advertising.[245] RTÉ operates two national television channels, RTÉ One and RTÉ Two. The other independent national television channels are Virgin Media One, Virgin Media Two, Virgin Media Three and TG4, the latter of which is a public service broadcaster for speakers of the Irish language. All these channels are available on Saorview, the national free-to-air digital terrestrial television service.[246] Additional channels included in the service are RTÉ News Now, RTÉjr, and RTÉ One +1. Subscription-based television providers operating in Ireland include Virgin Media and Sky.

The BBC's Northern Irish division is widely available in Ireland. BBC One Northern Ireland and BBC Two Northern Ireland are available in pay television providers including Virgin and Sky as well as via signal overspill by Freeview in border counties.

Supported by the Irish Film Board, the Irish film industry grew significantly since the 1990s, with the promotion of indigenous films as well as the attraction of international productions like Braveheart and Saving Private Ryan.[247]

A large number of regional and local radio stations are available countrywide. A survey showed that a consistent 85% of adults listen to a mixture of national, regional and local stations on a daily basis.[248] RTÉ Radio operates four national stations, Radio 1, 2fm, Lyric fm, and RnaG. It also operates four national DAB radio stations. There are two independent national stations: Today FM and Newstalk.

Ireland has a traditionally competitive print media, which is divided into daily national newspapers and weekly regional newspapers, as well as national Sunday editions. The strength of the British press is a unique feature of the Irish print media scene, with the availability of a wide selection of British published newspapers and magazines.[247]

Eurostat reported that 82% of Irish households had Internet access in 2013 compared to the EU average of 79% but only 67% had broadband access.[249]

Cuisine

Irish cuisine was traditionally based on meat and dairy products, supplemented with vegetables and seafood. Examples of popular Irish cuisine include boxty, colcannon, coddle, stew, and bacon and cabbage. Ireland is known for the full Irish breakfast, which involves a fried or grilled meal generally consisting of rashers, egg, sausage, white and black pudding, and fried tomato. Apart from the influence by European and international dishes, there has been an emergence of a new Irish cuisine based on traditional ingredients handled in new ways.[250] This cuisine is based on fresh vegetables, fish, oysters, mussels and other shellfish, and the wide range of hand-made cheeses that are now being produced across the country. Shellfish have increased in popularity, especially due to the high quality shellfish available from the country's coastline. The most popular fish include salmon and cod. Traditional breads include soda bread and wheaten bread. Barmbrack is a yeasted bread with added sultanas and raisins, traditionally eaten on Halloween.[251]

Popular everyday beverages among the Irish include tea and coffee. Alcoholic drinks associated with Ireland include Poitín and the world-famous Guinness, which is a dry stout that originated in the brewery of Arthur Guinness at St. James's Gate in Dublin. Irish whiskey is also popular throughout the country and comes in various forms, including single malt, single grain, and blended whiskey.[250]

Sports

Gaelic football and hurling are the traditional sports of Ireland as well as popular spectator sports.[252] They are administered by the Gaelic Athletics Association on an all-Ireland basis. Other Gaelic games organised by the association include Gaelic handball and rounders.[253]

Association football (soccer) is the third most popular spectator sport and has the highest level of participation.[254] Although the League of Ireland is the national league, the English Premier League is the most popular among the public.[255] The Republic of Ireland national football team plays at international level and is administered by the Football Association of Ireland.[256]

The Irish Rugby Football Union is the governing body of rugby union, which is played at local and international levels on an all-Ireland basis, and has produced players such as Brian O'Driscoll and Ronan O'Gara, who were on the team that won the Grand Slam in 2009.[257]

The success of the Irish Cricket Team in the 2007 Cricket World Cup has led to an increase in the popularity of cricket, which is also administered on an all-Ireland basis by Cricket Ireland.[258] Ireland are one of the twelve Test playing members of the International Cricket Council, having been granted Test status in 2017. Professional domestic matches are played between the major cricket unions of Leinster, Munster, Northern, and North West.

Netball is represented by the Ireland national netball team.

Golf is another popular sport in Ireland, with over 300 courses countrywide.[259] The country has produced several internationally successful golfers, such as Pádraig Harrington, Shane Lowry and Paul McGinley.

Horse racing has a large presence, with influential breeding and racing operations in the country. Racing takes place at courses at The Curragh Racecourse in County Kildare, Leopardstown Racecourse just outside Dublin, and Galway. Ireland has produced champion horses such as Galileo, Montjeu, and Sea the Stars.

Boxing is Ireland's most successful sport at an Olympic level. Administered by the Irish Athletic Boxing Association on an all-Ireland basis, it has gained in popularity as a result of the international success of boxers such as Bernard Dunne, Andy Lee and Katie Taylor.

Some of Ireland's highest performers in athletics have competed at the Olympic Games, such as Eamonn Coghlan and Sonia O'Sullivan. The annual Dublin Marathon and Dublin Women's Mini Marathon are two of the most popular athletics events in the country.[260]

Rugby league is represented by the Ireland national rugby league team and administered by Rugby League Ireland (who are full member of the Rugby League European Federation) on an all-Ireland basis. The team compete in the European Cup (rugby league) and the Rugby League World Cup. Ireland reached the quarter finals of the 2000 Rugby League World Cup as well as reaching the semi finals in the 2008 Rugby League World Cup.[261] The Irish Elite League is a domestic competition for rugby league teams in Ireland.[262]

While Australian rules football in Ireland has a limited following, a series of International rules football games (constituting a hybrid of the Australian and Gaelic football codes) takes place annually between teams representing Ireland and Australia.[263] Baseball and basketball are also emerging sports in Ireland, both of which have an international team representing the island of Ireland. Other sports which retain a following in Ireland include cycling, greyhound racing, horse riding, and motorsport.

Society

Ireland ranks fifth in the world in terms of gender equality.[264] In 2011, Ireland was ranked the most charitable country in Europe, and second most charitable in the world.[265] Contraception was controlled in Ireland until 1979, however, the receding influence of the Catholic Church has led to an increasingly secularised society.[266] A constitutional ban on divorce was lifted following a referendum in 1995. Divorce rates in Ireland are very low compared to European Union averages (0.7 divorced people per 1,000 population in 2011) while the marriage rate in Ireland is slightly above the European Union average (4.6 marriages per 1,000 population per year in 2012). Abortion had been banned throughout the period of the Irish state, first through provisions of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 and later by the Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act 2013. The right to life of the unborn was protected in the constitution by the Eighth Amendment in 1983; this provision was removed following a referendum, and replaced it with a provision allowing legislation to regulate the termination of pregnancy. The Health (Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy) Act 2018 passed later that year provided for abortion generally during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, and in specified circumstances after that date.[267]

Capital punishment is constitutionally banned in Ireland, while discrimination based on age, gender, sexual orientation, marital or familial status, religion, race or membership of the travelling community is illegal. The legislation which outlawed homosexual acts was repealed in 1993.[268][269] The Civil Partnership and Certain Rights and Obligations of Cohabitants Act 2010 permitted civil partnerships between same-sex couples.[270][271][272] The Children and Family Relationships Act 2015 allowed for adoption rights for couples other than married couples, including civil partners and cohabitants, and provided for donor-assisted human reproduction; however, significant sections of the Act have yet to be commenced.[273] Following a referendum held on 23 May 2015, Ireland became the eighteenth country to provide in law for same-sex marriage, and the first to do so by popular vote.[274]