Montana-class battleship

The Montana-class battleships were planned as successors of the Iowa class for the United States Navy, to be slower but larger, better armored, and with superior firepower. Five were approved for construction during World War II, but changes in wartime building priorities resulted in their cancellation in favor of continuing production of Essex-class aircraft carriers and Iowa-class battleships before any Montana-class keels were laid.

A 1944 model of a Montana-class battleship on top of filing cabinets | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Montana-class battleship |

| Builders |

|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Iowa class |

| Succeeded by | N/A, last battleship class authorized |

| Planned | 5 |

| Completed | 0 |

| Cancelled | 5 |

| General characteristics (Design BB67-4) | |

| Displacement |

|

| Length |

|

| Beam | 121 ft 2 in (36.93 m) |

| Draft | 36 ft 0 in (10.97 m) |

| Installed power | 8 × Babcock & Wilcox 2-drum express type boilers powering 4 sets of Westinghouse geared steam turbines 4 × 43,000 hp (32 MW) – 172,000 hp (128 MW) total power |

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts 2 × rudders |

| Speed | 28 kn (32 mph; 52 km/h) maximum[3] |

| Range | 15,000 nmi (17,300 mi; 27,800 km) at 15 kn (17 mph; 28 km/h)[4] |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

| Aircraft carried | 3–4 × Vought OS2U Kingfisher/Curtiss SC Seahawk floatplanes |

| Aviation facilities | 2 × aft catapults for launch of seaplanes |

| Notes | This was the last battleship class designed for the United States Navy; the class was cancelled before any of the ships' keels were laid. |

Their intended armament would have been twelve 16-inch (406 mm) Mark 7 guns in four 3-gun turrets, up from the nine Mark 7 guns in three turrets used by the Iowa class. Unlike the three preceding classes of battleships, the Montana class was designed without any restrictions from treaty limitations. With an increased anti-aircraft capability and substantially thicker armor in all areas, the Montanas would have been the largest, best-protected, and most heavily armed US battleships ever. They also would have been the only class to rival the Empire of Japan's Yamato-class battleships in terms of tonnage.[5]

Preliminary design work for the Montana class began before the US entry into World War II. The first two vessels were approved by Congress in 1939 following the passage of the Second Vinson Act. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor delayed the construction of the Montana class. The success of carrier combat at the Battle of the Coral Sea and, to a greater extent, the Battle of Midway, diminished the perceived value of the battleship. Consequently, the US Navy chose to cancel the Montana class in favor of more urgently needed aircraft carriers as well as amphibious and anti-submarine vessels.[N 1]

Because the Iowas were far enough along in construction and urgently needed to operate alongside the new Essex-class aircraft carriers, their orders were retained,[7] making them the last US Navy battleships to be commissioned.

History

As the political situation in Europe and Asia deteriorated in the prelude to World War II, Carl Vinson, the chairman of the House Committee on Naval Affairs, instituted the Vinson Naval Plan. It aimed to get the Navy into fighting shape after the cutbacks imposed by the Great Depression and the two London Naval Treaties of the 1930s.[8][9] As part of the overall plan, Congress passed the Second Vinson Act in 1938, which was promptly signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and cleared the way for construction of the four South Dakota-class fast battleships and the first two Iowa-class fast battleships (hull numbers BB-61 and BB-62).[10] Four additional battleships (with hull numbers BB-63, BB-64, BB-65, and BB-66) were approved for construction on 12 July 1940,[10] with the last two intended to be the first ships of the Montana class.[11]

The Navy had been considering large battleship design schemes since 1938 to counter the threat posed by potential battleships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, which had refused to sign the Second London Naval Treaty and furthermore refused to provide details about its Yamato-class battleships. Although the Navy knew little about the Yamato class, some rumors regarding the new Japanese battleships placed their main gun battery caliber at 18 inches (457 mm).[N 2] The potential of naval treaty violations by the new Japanese battleships resulted in the remaining treaty powers, Britain, France, and the United States, invoking the tonnage "Escalator Clause" of the Second London Naval Treaty in June 1938,[N 3] which raised the maximum standard displacement limit from 35,000 long tons (36,000 t) to 45,000 long tons (46,000 t).[14][10][N 4]

The increased displacement limit allowed the Navy to begin evaluating 45,000-ton battleship designs, including "slow" 27-knot (50 km/h; 31 mph) schemes that increased firepower and protection over previous designs and also "fast" 33-knot (61 km/h; 38 mph) schemes. The "fast" design evolved into the Iowa class while the "slow" design, with main armament battery eventually settled on twelve 16-inch (406 mm) guns and evolution into a 60,500-ton design, was assigned the name Montana and cleared for construction by the United States Congress under the Two-Ocean Navy Act on 19 July 1940; funding for the new ships was approved in 1941. The five ships, the last battleships to be ordered by the Navy, were originally to be designated BB-65 through BB-69; however, BB-65 and BB-66 were subsequently re-ordered as Iowa-class ships, Illinois and Kentucky, in the Two Ocean Navy Act due to the urgent need for more warships, and the Montanas were redesignated BB-67 through BB-71.[17]

.jpg.webp)

Completion of the Montana class, and the last two Iowa-class battleships, was intended to give the US Navy a considerable advantage over any other nation, or probable combination of nations, with a total of 17 new battleships by the late 1940s.[N 5] The Montanas also would have been the only American ships to rival Japan's massive Yamato and her sister Musashi in size and raw firepower.[5]

Design

Preliminary planning for the Montana-class battleships took place in 1939, when the aircraft carrier was still considered strategically less important than the battleship. The initial schemes for what would eventually become the Montana class were continuations of various 1938 design studies for a 45,000-ton "slow" battleship alternative to the "fast" battleship design that would become the Iowa class. The "slow" battleship design proposals had a maximum speed of 27–28 knots (31–32 mph; 50–52 km/h) and considered various main gun battery options, including 16-inch (406 mm)/45 cal, 16-inch/50 cal, 16-inch/56 cal, and 18-inch (457 mm)/48 cal guns;[N 6] a main battery of twelve 16-inch/50 cal guns was eventually selected by the General Board for offering the best combination of performance and weight.[18] The initial design schemes for the Montana class were given the "BB65" prefix.[19][20]

In July 1939, a series of 45,000-ton BB-65 design schemes were evaluated, but in February 1940, as a result of the outbreak of World War II and the abandonment of the naval treaties, the Battleship Design Advisory Board moved to larger designs capable of simultaneously offering increased armament and protection.[5][19] The design board issued a basic outline for the Montana class that called for it to be free of beam restrictions imposed by the extant Panama Canal, be 25% stronger offensively and defensively than any other battleship completed or under construction, and be capable of withstanding the new "super heavy" 2,700 lb (1,225 kg) armor-piercing (AP) shells used by US battleships equipped with either the 16-inch/45 cal guns or 16-inch/50 cal Mark 7 guns. No longer restricted by treaty displacement limits, naval architects were able to increase armor protection for the new BB65 design schemes, enabling the ships to withstand enemy fire equivalent to their own guns' ammunition. In conjunction with the Montana class, the Navy also planned to add a third set of locks to the Panama Canal that would be 140 ft (43 m) wide to enable ship designs with greater beams; these locks would have been armored and would normally be reserved for use by Navy warships.[19] Although freed of the beam restriction from the extant Panama Canal, the length and height of the BB65 designs had to take into account one of the shipyards at which they were to be built: the New York Navy Yard slipways could not handle the construction of a ship more than 58,000 long tons (59,000 t), and vessels built there had to be low enough to clear the Brooklyn Bridge at low tide.[N 7] Consequently, the yard's number 4 dry dock had to be enlarged and the ships would be floated out rather than conventionally launched.[21]

.jpg.webp)

The larger BB-65 design studies would again settle on a main armament of twelve 16-inch/50 cal guns while providing protection against the "super heavy" AP shells. After debate at the design board about whether the Montana class should be fast, achieving the high 33-knot (38 mph; 61 km/h) speed of the Iowa class, or maintain the 27-to-28-knot speed of the North Carolina and South Dakota classes, the lower speed was chosen in order to rein in size and displacement.[5] Design study of the BB-65-8 scheme for a 33-knot battleship resulted in a standard displacement of over 66,000 long tons (67,000 t), a waterline length of 1,100 feet (340 m), and a requirement of 320,000 shaft horsepower (239 MW); by returning the BB-65 design to the slower maximum speed, the standard displacement and waterline length of the ships could be reduced to a more practical 58,000 long tons (59,000 t) and 930 feet (280 m), respectively, as exemplified by the BB65-5 scheme.[22][23] In practice, the 27-to-28-knot speed would have still been enough to escort and defend the Pacific-based Allied fast aircraft carrier task forces, although the Montanas' ability in this regard would be considerably more limited compared to the Iowas as the latter could keep up with fleet carriers at full speed.[5][10] In September 1940, the 58,000-ton BB65-5A preliminary design scheme with a 212,000-shaft-horsepower (158 MW) powerplant, the same as the one on Iowa class, was refined and subsequently named BB-67-1 after hull numbers BB-65 and 66 were reallocated as Iowa-class ships Illinois and Kentucky. Waterline length was reduced from 930 feet (283.5 m) for BB65-5 to 880 feet (268.2 m) for BB65-5A and then increased to 890 feet (271.3 m) for BB67-1.[24][23]

By January 1941, the design limit for the 58,000-ton battleship plan had been reached, and consensus among those designing the battleship class was to increase the displacement to a nominal 60,500 long tons (61,470 t) to support the desired armor and weaponry on the ships.[25] At the same time, upon discovering that the propulsion plant was more powerful than needed, planners decided to reduce output from 212,000 shaft horsepower in BB67-2 to 180,000 shaft horsepower (134 MW) in BB67-3 for a better machinery arrangement and improved internal subdivisions. The secondary armament battery of ten two-gun turrets was also changed to mount the 5-inch (127 mm)/54 cal guns instead of the 5-inch/38 cal guns used on the Iowas. The number of 40-mm Bofors anti-aircraft gun mounts also increased, while protection of the propulsion shafts changed from the extension of the belt and deck armor aft of the citadel to armored tubes in an effort to control weight growth.[26][27]

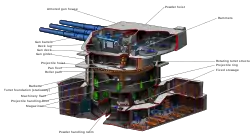

By 1942, the Montana class design was further revised to BB-67-4. The armored freeboard was increased by 1 foot (0.30 m), while the propulsion plant had its power reduced again to 172,000 horsepower (128 MW); the standard displacement became 63,221 long tons (64,240 t) and full load displacement was 70,965 long tons (72,100 t). Aesthetically, the net design for the Montana class somewhat resembled the Iowa class since they would be equipped with the same caliber main guns and similar secondary guns; however, Montana and her sisters would have more armor, mount three more main guns in one more turret, and be 34 ft (10 m) longer and 13 ft (4.0 m) wider than the Iowa class.[5] The final contract design was issued in June 1942. Construction was authorized by the United States Congress and the projected date of completion was estimated to be somewhere between 1 July and 1 November 1945.[2][28]

Fate

The Navy ordered the ships in May 1942, but the Montana class was placed on hold because the Iowa-class battleships and the Essex-class aircraft carriers were under construction in the shipyards intended to build the Montanas. Both the Iowa and Essex classes had been given higher priorities: the Iowas as they were far along enough in construction and urgently needed to operate alongside the Essex-class carriers and defend them with 5-inch, 40 mm, and 20 mm AA guns, and the Essexes because of their ability to launch aircraft to gain and maintain air supremacy over the islands in the Pacific and intercept warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The entire Montana class was suspended in June 1942 following the Battle of Midway, before any of their keels had been laid. In July 1943, the construction of the Montana class was finally cancelled after the Navy fully accepted the shift in naval warfare from surface engagements to air supremacy and from battleships to aircraft carriers.[5][10][29] Work on the new locks for the Panama Canal also ceased in 1941, owing to a shortage of steel due to the changing strategic and material priorities.[19][N 8]

Specifications

General characteristics

The final BB-67-4 design for the Montana-class battleships was 890.0 ft (271.27 m) long at the waterline and 921.2 ft (280.77 m) long overall. The maximum beam was 121.2 ft (36.93 m) while the waterline beam was 115.0 ft (35.05 m) due to the inclination of the external armor belt. The design displacement figures were 63,221 long tons (64,236 t) standard, 70,965 long tons (72,104 t) full load, and 71,922 long tons (73,076 t) emergency load.[N 9] At emergency load displacement, the mean draft was 36.85 ft (11.23 m). At design combat displacement of 68,317 long tons (69,413 t), the mean draft was 35.11 ft (10.70 m), and (GM) metacentric height was 8.14 feet (2.48 m).[31][32]

The Montana design shares many characteristics with the previous classes of American fast battleships starting from the North Carolina class, such as a bulbous bow, triple bottom under the armored citadel, and twin skegs in which the inner shafts were housed. The Montanas' overall construction would have made extensive use of welding for joining structural plates and homogeneous armor.[32]

Armament

The armament of the Montana-class battleships would have been similar to the preceding Iowa-class battleships, but with an increase in the number of primary guns and more potent secondary guns for use against enemy surface ships and aircraft. Had they been completed, the Montanas would have been gun-for-gun the most powerful battleships the United States had constructed, and the only US battleship class that would have rivaled the Imperial Japanese Navy battleships Yamato and Musashi in armament, armor, and displacement.[5]

Main battery

The primary armament of a Montana-class battleship would have been twelve 16-inch (406 mm)/50 caliber Mark 7 guns, which were to be housed in four three-gun turrets: two forward and two aft. The guns, the same used to arm the Iowa-class battleships, were 66 ft (20 m) long—50 times their 16-inch (406 mm) bore, or 50 calibers, from breechface to muzzle. Each gun weighed about 239,000 lb (108,000 kg) without the breech, or 267,900 lb (121,500 kg) with the breech.[33] They fired 2,700 lb (1,225 kg) armor-piercing projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 2,500 ft/s (762 m/s), or 1,900 lb (862 kg) high-capacity projectiles at 2,690 ft/s (820 m/s), with a range of up to 24 mi (39 km). At maximum range, the projectile would have spent almost 1½ minutes in flight.[33] The addition of the No. 4 turret would have allowed Montana to overtake Yamato as the battleship having the heaviest broadside overall; Montana and her sisters would have had a broadside of 32,400 lb (14,700 kg)[5] vs. 28,800 lb (13,100 kg) for Yamato.[N 10] Each turret would have rested within an armored barbette, but only the top of the barbette would have protruded above the main deck. The barbettes would have extended either four decks (turrets 1 and 4) or five decks (turrets 2 and 3) down. The lower spaces would have contained rooms for handling the projectiles and storing the powder bags used to fire them. Each turret would have required a crew of 94 men to operate.[33] The turrets would not have been attached to the ship but would have rested on rollers; had any of the Montana-class ships capsized, the turrets would have fallen out.[N 11] Each turret would have cost US$1.4 million, but this figure did not take into account the cost of the guns themselves.[33]

The turrets would have been "three-gun", not "triple", because each barrel would have elevated and fired independently. The ships could fire any combination of their guns, including a broadside of all twelve. Contrary to popular belief, the ships would not have noticeably moved sideways when a broadside was fired.[37] The guns would have had an elevation range of −5° to +45°, moving at up to 12° per second. The turrets would have rotated about 300° at about 4° per second and could even be fired back beyond the beam, which is sometimes called "over the shoulder". Within each turret, a red stripe on the wall of the turret, just inches from the railing, would have marked the boundary of the gun's recoil, providing the crew of each gun turret with a visual reference for the minimum safe distance range.[38]

Like most US battleships in World War II, the Montana class would have been equipped with a fire control computer—in this case, the Ford Instrument Company Mk 1A Ballistic Computer, a 3,150 lb (1,430 kg) rangekeeper designed to direct gunfire on land, sea, and in the air. This analog computer would have been used to direct the fire from the battleship's main guns, taking into account several factors, such as the speed of the targeted ship, the time it takes for a projectile to travel, and air resistance to the shells fired at a target. At the time the Montana class was set to begin construction, the rangekeepers had gained the ability to use radar data to help target enemy ships and land-based targets. The results of this advance were telling: the rangekeeper was able to track and fire at targets at a greater range and with increased accuracy, as was demonstrated in November 1942 when the battleship Washington engaged the Imperial Japanese Navy battleship Kirishima at a range of 18,500 yd (16.9 km) at night; Washington scored at least nine heavy caliber hits that critically damaged the Kirishima and led to her loss.[40][41] This gave the US Navy a major advantage in World War II, as the Japanese did not develop radar or automated fire control to the level of the US Navy.[40]

"When you're penetrating armor, there is a thing called frontal density – it's not just the weight of the shell, it's the weight of the shell trying to punch a hole through [the armor]. Well, the 16"/50 heavy shell was almost as good an armor penetrator as the Japanese 18.1" shell."

Philip Simms, naval architect[42]

The large caliber guns were designed to fire two different 16-inch shells: an armor-piercing round for anti-ship and anti-structure work, and a high-explosive round designed for use against unarmored targets and shore bombardment. The Mk. 8 APC (Armor-Piercing, Capped) shell weighed in at 2,700 lb (1,225 kg) and was designed to penetrate the hardened steel armor carried by foreign battleships. At 20,000 yd (18.3 km), the Mk. 8 could penetrate 20 inches (510 mm) of vertical steel armor plate.[43] For unarmored targets and shore bombardment, the 1,900 lb (862 kg) Mk. 13 HC (High-Capacity —referring to the large bursting charge) shell was available.[43] The Mk. 13 shell could create a crater 50 ft (15 m) wide and 20 ft (6.1 m) deep upon impact and detonation and could defoliate trees 400 yd (370 m) from the point of impact.

The final type of ammunition developed for the 16-inch guns, well after the Montanas had been cancelled, were W23 "Katie" shells. These were born from the nuclear deterrence that had begun to shape the US armed forces at the start of the Cold War. To compete with the United States Air Force and the United States Army, which had developed nuclear bombs and nuclear shells for use on the battlefield, the Navy began a top-secret program to develop Mk. 23 nuclear naval shells with an estimated yield of 15 to 20 kilotons. The shells entered development around 1953, and were reportedly ready by 1956; however, only the Iowa-class battleships could have fired them.[43][44]

Secondary battery

The secondary armament for Montana and her sisters was to be twenty 5-inch (127 mm)/54 cal guns housed in ten turrets along the superstructure island of the battleship: five on the starboard side and five on the port. These guns, designed specifically for the Montanas, were to be the replacement for the 5-inch (127 mm)/38 cal secondary gun batteries then in widespread use with the US Navy.

The 5-inch/54 cal gun turrets were similar to the 5-inch/38 cal gun mounts in that they were equally adept in an anti-aircraft role and for damaging smaller ships, but differed in that they weighed more and fired heavier rounds of ammunition at greater velocities, thus increasing their effectiveness. However, the heavier rounds resulted in faster crew fatigue than the 5-inch/38 cal guns.[46] The ammunition storage for the 5-inch/54 cal gun was 500 rounds per turret, and the guns could fire at targets nearly 26,000 yd (24 km) away at a 45° angle. At an 85° angle, the guns could hit an aerial target at over 50,000 ft (15,000 m).

The cancellation of the Montana-class battleships in 1943 pushed back the combat debut of the 5-inch/54 cal guns to 1945, when they were used aboard the US Navy's Midway-class aircraft carriers. The guns proved adequate for the carrier's air defense, but they were gradually phased out of use by the carrier fleet because of their weight. (Rather than having the carrier defend itself by gunnery, this would be assigned to other surrounding ships within a carrier battle group.)

Anti-aircraft batteries

While the Montana class was not designed principally for escorting the fast carrier task forces, they would have nonetheless been equipped with a wide array of anti-aircraft guns to protect themselves and other ships (principally the US aircraft carriers) from Japanese fighters and dive bombers. If commissioned, the ships were expected to mount a considerable array of Oerlikon 20 mm and Bofors 40 mm anti-aircraft weapons.

_Oerlikon_20mm_AA_gun_mount.jpg.webp)

The Oerlikon 20 mm anti-aircraft cannon was one of the most heavily produced anti-aircraft guns of World War II; the US alone manufactured a total of 124,735 of these guns. When activated in 1941, these guns replaced the .50 in (12.7 mm)/90 cal M2 Browning MG on a one-for-one basis. The Oerlikon 20 mm AA gun remained the primary anti-aircraft weapon of the United States Navy until the introduction of the 40 mm Bofors AA gun in 1943.[47]

These guns are air-cooled and use a gas blow-back recoil system. Unlike other automatic guns employed during World War II, the barrel of the 20 mm Oerlikon gun does not recoil; the breechblock is never locked against the breech and is actually moving forward when the gun fires. This weapon lacks a counter-recoil brake, as the force of the counter-recoil is checked by recoil from the firing of the next round of ammunition.[47] Between December 1941 and September 1944, 32% of all Japanese aircraft downed were credited to this weapon, with the high point being 48% for the second half of 1942. In 1943, the revolutionary Mark 14 gunsight was introduced, which made these guns even more effective. The 20 mm guns, however, were found to be ineffective against the Japanese kamikaze attacks used during the latter half of World War II. They were subsequently phased out in favor of the heavier 40 mm Bofors AA guns.[47]

The Bofors 40 mm anti-aircraft gun was used on almost every major warship in the US and UK fleet from about 1943 to 1945. Although a descendant of German, Dutch, and Swedish designs, the Bofors mounts used by the US Navy during World War II had been heavily Americanized to bring the guns up to the standards placed on them by the Navy. This resulted in a gun system set to British standards (now known as the Standard System) with interchangeable ammunition, which simplified the logistics situation for World War II. When coupled with hydraulic couple drives to reduce salt contamination and the Mark 51 director for improved accuracy, the Bofors 40 mm gun became a fearsome adversary, accounting for roughly half of all Japanese aircraft shot down between 1 October 1944 and 1 February 1945.[48]

Propulsion

The propulsion plant of the Montanas would have consisted of eight Babcock & Wilcox two-drum boilers with a steam pressure of 565 psi (3,900 kPa) and a steam temperature of 850 °F (454 °C) feeding four geared steam turbines, each driving one shaft with 43,000 hp (32 MW); this would result in a total propulsive power of 172,000 hp (128 MW), which gave a design speed of 28 knots at 70,500 tons displacement.[49][N 12] While less powerful than the 212,000 hp (158,000 kW) powerplant used by the Iowas, the Montana's plant enabled the machinery spaces to be considerably more subdivided, with extensive longitudinal and traverse subdivisions of the boiler and engine rooms. The machinery arrangement was reminiscent of that of the Lexington-class aircraft carrier, with the boiler rooms flanking the two central turbine rooms for the inboard shafts, while the turbine rooms for the wing shafts were placed at the after end of the machinery spaces.[27] Montana's machinery arrangement combined with increased power would eventually be used on the Midway-class aircraft carrier.[50] The Montanas were designed to carry 7,500 long tons (7,600 t) of fuel oil and had a nominal range of 15,000 nmi (27,800 km; 17,300 mi) at 15 kn (28 km/h; 17 mph). Two semi-balanced rudders were placed behind the two inboard screws. The inboard shafts were housed in skegs, which, while increasing hydrodynamic drag, substantially strengthened the stern structure.[N 13]

To meet the high electrical loads anticipated for the ships, the design was to have ten 1,250 kW ship service turbogenerators (SSTG), providing a total of 12,500 kW of non-emergency electrical power at 450 volts alternating current. The ships were also to be equipped with two 500 kW emergency diesel generators.[25]

Armor

Aside from its firepower, a battleship's defining feature is its armor. The exact design and placement of the armor, inextricably linked with the ship's stability and performance, is a complex science honed over decades.[52] A battleship is usually armored to withstand an attack from guns the size of its own, but the armor scheme of the preceding North Carolina class was only proof against 14-inch (356 mm) shells (which they had originally been intended to carry), while the South Dakota and Iowa classes were designed only to resist their original complement of 16-inch (406 mm) 2,240 lb (1,016 kg) Mk. 5 shells, not the new "super-heavy" 2,700 lb (1,225 kg) Mk. 8 armor-piercing shells they actually used. The Montanas were the only US battleships designed to resist the Mk. 8.[10] They were designed to give a zone of immunity against fire from 16-inch/45-caliber firing 2,700 lb shell, between 18,000 and 31,000 yards (16,000 and 28,000 m) and 16-inch/45-caliber firing 2,240 lb shell, between 16,500 and 34,500 yards (15,100 and 31,500 m) away.[53]

As designed, the Montanas used the "all or nothing" armor philosophy, with most of the armor concentrated on the citadel that includes the machinery spaces, armament, magazines, and command and control facilities. Unlike the previous Iowa and South Dakota classes, the Montana class design returned to an external armor belt due to the greater beam providing sufficient stability while having the required belt inclination; this arrangement would have made construction and damage repairs much easier. The belt armor would be 16.1 in (409 mm) Class A face-hardened Krupp cemented (K.C.) armor mounted on 1 in (25 mm) Special Treatment Steel (STS), inclined at 19 degrees. Below the waterline, the belt tapered to 10.2 in (259 mm). To protect against potential underwater shell hits, the ships would have a separate Class B homogeneous Krupp-type armor lower belt, 8.5 in (216 mm) by the magazines and 7.2 in (183 mm) by the machinery, that would also have served as one of the torpedo bulkheads, inclined at 10 degrees; this lower belt would taper to 1 inch at the triple bottom and be mounted on 0.75 in (19 mm) STS. The ends of the armored citadel would be closed by Class A traverse bulkheads 18 in (457 mm) thick in the front and 15.25 in (387 mm) in the aft. The deck armor would be in three layers: the first consisting of 0.75 in (19 mm) STS laminated on 1.5 in (38 mm) STS for a total of 2.25 in (57 mm) STS weather deck, the second consisting of 5.8 in (147 mm) Class B laminated on 1.25 in (32 mm) STS for a total of 7.05 in (179 mm), and a third 0.625 in (16 mm) splinter deck. Over the magazines, the splinter deck would be replaced by a 1 in (25 mm) STS third deck to protect from spalling. Total armor thickness on the centerline would therefore have been 9.925 in (252 mm) over the citadel and 10.3 in (262 mm) thick over the magazines. The outboard section would have had 6.1 in (155 mm) Class B laminated on 1.25 in (32 mm) STS for a total of 7.35 in (187 mm) second deck and a 0.75 in (19 mm) splinter deck. The total thickness for the outboard section of the deck would have been 8.1 in (206 mm).[53]

The main batteries were designed to have very heavy protection, with turret faces having 18 in (457 mm) Class B mounted on 4.5 in (114 mm) STS, resulting in 22.5 in (572 mm) thick laminated plate. The turret sides were to have up to 10 in (254 mm) Class A and turret roofs would have 9.15 in (232 mm) Class B. The barbettes would have been protected by up to 21.3 in (541 mm) Class A forward and 18 in (457 mm) aft, while the conning tower sides would have 18 in (457 mm) Class A.[54]

Montana's torpedo protection system design incorporated lessons learned from those of previous US fast battleships, and was to consist of four internal longitudinal torpedo bulkheads behind the outer hull shell plating that would form a multi-layered "bulge". Two of the compartments would be liquid loaded in order to disrupt the gas bubble of a torpedo warhead detonation while the bulkheads would elastically deform and absorb the energy. Due to the external armor belt, the geometry of the "bulge" was more similar to that of the North Carolina class rather than that of the South Dakota and Iowa classes.[N 14] Like on the South Dakota and Iowa classes, the two outer compartments would be liquid loaded, while two inner ones be void with the lower Class B armor belt to form the holding bulkhead between them. The greater beam of the Montanas would allow a higher system depth of 20.5 ft (6.25 m) compared to 18.5 ft (5.64 m) of the North Carolinas.[56]

Until the authorization of the Montana class, all US battleships were built within the size limits of the Panama Canal. The main reason for this was logistical: the largest US shipyards were located on the East Coast of the United States, while the United States had territorial interests in both oceans.[10] Requiring the battleships to fit within the Panama Canal took days off the transition time from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean by allowing ships to move through the canal instead of sailing around South America.[N 15] By the time of the Two Ocean Navy bill, the Navy realized that ship designs could no longer be limited by the extant Panama Canal and thus approved the Montana class while simultaneously planning for a new third set of locks that were 140 ft (43 m) wide.[10] This shift in policy meant that the Montana class would have been the only World War II–era US battleships to be adequately armored against guns of the same power as their own.

Aircraft

_Stern.jpg.webp)

The Montana class would have used aircraft for reconnaissance and gunnery spotting.[5] The type of aircraft used would have depended on when exactly the battleships would have been commissioned, but in all probability, they would have used either the Kingfisher or the Seahawk.[N 16] The aircraft would have been floatplanes launched from catapults on the ship's fantail.[5] They would have landed on the water and taxied to the stern of the ship to be lifted by a crane back to the catapult.

Kingfisher

The Vought OS2U Kingfisher was a lightly armed two-man aircraft designed in 1937. The Kingfisher's high operating ceiling of 13,000 feet (4.0 km) made it well-suited for its primary mission: to observe the fall of shot from a battleship's guns and radio corrections back to the ship. The floatplanes used in World War II also performed search and rescue for naval aviators who were shot down or forced to ditch in the ocean.[58]

Seahawk

In June 1942, the US Navy Bureau of Aeronautics requested industry proposals for a new seaplane to replace the Kingfisher and Curtiss SO3C Seamew. The new aircraft was required to be able to use landing gear as well as floats.[59] Curtiss submitted a design on 1 August and received a contract for two prototypes and five service-test aircraft on 25 August.[59] The first flight of a prototype XSC-1 took place on 16 February 1944 at the Columbus, Ohio Curtiss plant. The first production aircraft were delivered in October 1944, and by the beginning of 1945, the single-seat Curtiss SC Seahawk floatplane began replacing the Kingfisher. Had the Montana class been completed, they would have arrived around the time of this replacement, and would likely have been equipped with the Seahawk for use in combat operations and seaborne search and rescue.[5]

Ships

Five ships of the Montana class were authorized on 19 July 1940, but they were suspended indefinitely until being cancelled on 21 July 1943. The ships were to be built at the New York Navy Yard, Philadelphia Navy Yard, and Norfolk Navy Yard.

USS Montana (BB-67)

Montana was planned to be the lead ship of the class. She was the third ship to be named in honor of the 41st state, and she was assigned to the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Both the earlier battleship, BB-51, and BB-67 were cancelled, so Montana is the only one of the (48 at the time) US states never to have had a battleship with a "BB" hull classification completed in its honor.[60][61][N 17]

USS Ohio (BB-68)

Ohio was to be the second Montana-class battleship. She was to be named in honor of the 17th state, and she was assigned to the Philadelphia Navy Yard for construction. Ohio would have been the fourth ship to bear that name had she been commissioned.[62][63]

USS Maine (BB-69)

Maine was to be the third Montana-class battleship. She was to be named in honor of the 23rd state, and she was assigned to the New York Navy Yard. Maine would have been the third ship to bear that name had she been commissioned.[64][65]

USS New Hampshire (BB-70)

New Hampshire was to be the fourth Montana-class battleship. She was to be named in honor of the ninth state, and she was assigned to the New York Navy Yard. New Hampshire would have been the third ship to bear that name had she been commissioned.[66][67]

USS Louisiana (BB-71)

Louisiana was to be the fifth and final Montana-class battleship. She was to be named in honor of the 18th state, and she was assigned to the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Virginia. Louisiana would have been the third ship to bear that name had she been commissioned.[68][69] By hull number, Louisiana was the last American battleship authorized for construction.[N 18]

See also

- H-class battleship proposals – comparable German battleship design (cancelled)

- Design A-150 battleship – comparable Japanese battleship design follow-on to the Yamato (cancelled)

- Lion-class battleship – comparable battleship design of the Royal Navy (first two ships laid down, both scrapped due to the start of the war in Europe)

Notes

- In theory, the US Navy could resume construction of battleships by building the Montana-class battleships but the maintenance, cost, and vulnerability of battleships in modern warfare make this an unlikely and unattractive option.[6]

- The dimensions of the Yamato class were so well concealed that the US only gleaned details from intercepted Imperial Japanese Navy intelligence reports.[12] Although rumored to be carrying 18.1-inch guns the United States Navy did not believe that the Empire of Japan had the technological know-how to engineer such a high caliber gun, and thus estimated that the Yamato class would mount 16-inch (406 mm) guns.[13]

- This tonnage "Escalator Clause" is distinct from the "Escalator Clause" invoked in April 1937 that raised the caliber limit from 14 in (356 mm) to 16 in (406 mm).

- In fact, Japan did grossly violate the London Naval Treaty with the Yamato-class battleships, as the US Navy would discover in the final years of World War 2.[15][16]

- These 17 battleships were authorized after the treaty agreements from the Second London Naval Conference expired on 1 January 1937,[3] and include the North Carolina-class battleships North Carolina and Washington, the South Dakota-class battleships South Dakota, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Alabama, the Iowa-class battleships Iowa, New Jersey, Missouri, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Kentucky, and the Montana-class battleships Montana, Ohio, Maine, New Hampshire, and Louisiana.

- One of the BB65 design schemes from 1939 also incorporated the 14-inch (356 mm)/50 cal guns.

- The Essex-class aircraft carriers encountered the same clearance problems early in their construction.[5]

- A third set of even wider locks—these ones 180 ft (54.86 m) in width, as opposed to the preexisting 110 ft (33.53 m)-wide locks and the 140 ft (42.67 m)-wide locks proposed by the WWII-era expansion project—was built much later, however, opening in 2016, although this was driven by increases in cargo ship size rather than warship size.

- These would have been the heaviest warships in the US Navy at the time of their commissioning; and would have remained the class with the greatest displacement until the commissioning of the Forrestal-class aircraft carriers, which weighed 79,300 long tons (80,600 t) fully loaded.[30]

- Mathematically this conclusion can by arrived at by dividing the overall broadside for the Yamato class and the Iowa class: each gun aboard a Yamato-class battleship was designed to fire a 3,200 pounds (1,500 kg) projectile;[34] multiplied by nine this gives a Yamato-class ship a 28,800 pounds (13,100 kg) broadside. Each Iowa-class battleship gun can fire a 2,700 pounds (1,225 kg) shell;[35] multiplied by twelve this gives a broadside of 32,400 pounds (14,700 kg).

- During his investigation of the wreck of the German battleship Bismarck oceanographer Robert D. Ballard and his team found four large empty barbettes that had once held the turrets Anton, Bruno, Caesar, and Doris. Ballard noted in his book Exploring the Bismarck that, "None of the four big turrets [were] still attached to the ship", each having fallen out when the battleship capsized and sank.[36]

- As the class was never completed, the true speed these battleships would have reached during trials remains educated predictions; 27–28 knots has frequently been cited as the probable speed based on the known speed of the Iowa class, calculations used in the hull design of the Iowa- and Montana-class ships, and the known power-output limits for ship engines at this time.[7]

- This was the result from revised model basin tests that showed additional drag from skegs, in contrast to the conclusions from the earlier basin tests for the North Carolina class.[51]

- The design of the Montana's torpedo defense system addressed a potential vulnerability of the South Dakota-type system, where caisson tests in 1939 showed that extending the main armor belt that tapers to the keel to act as one of the torpedo bulkheads had detrimental flooding effects due to the belt's rigidity. South Dakota's and Iowa's systems were modified in light of these tests, and Iowa's system was also further reinforced.[55]

- Sailing battleships around South America was unusual, but had been done by the battleship USS Oregon (BB-3) during the Spanish–American War.[57]

- As the class was never completed, determining the actual aircraft that would have been used aboard the battleships remains, at best, educated guesswork. Given that the floatplanes active at the estimated completion timeframe of 1 July – 1 November 1945 were the Kingfisher and the Seahawk, it stands to reason that one of these two floatplanes would have been selected for use aboard the battleship class.

- This is not counting Alaska and Hawaii, as they were insular areas until after the battleship age.

- USS Kentucky was the highest numbered battleship hull to have been under construction but not completed for the US Navy.[70] USS Wisconsin (BB-64) is numerically the highest numbered US battleship built, although she was actually completed before USS Missouri (BB-63), making Missouri the last completed US battleship. USS Wisconsin was commissioned on 16 April 1944,[71] while USS Missouri was commissioned on 11 June 1944.[72]

References

- Garzke and Dulin, p. 164.

- Johnston, Ian; McAuley, Rob (2002). The Battleships. London: Channel 4 Books (an imprint of Pan Macmillan, LTD). p. 122. ISBN 0-7522-6188-6.

- "US Battleships". USS Missouri Memorial Association. Archived from the original on 21 August 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- Minks, R. L. (September 2006). "Montana class battleships end of the line". Sea Classics. Canoga Park, California: Challenge Publications. OCLC 3922521.

- Government Accountability Office (19 November 2004). "Information on Options for Naval Surface Fire Support" (PDF). GAO report number GAO-05-39R. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- Department of the Navy. "Montana Class (BB-67 through BB-71)". Naval Historical Center. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- Cook, James F. (11 July 2002). "Carl Vinson (1883–1981)". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. University of Georgia. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- United States Navy. "The Vinson Naval Plan". United States Navy. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- Rogers, J. David. "Development of the World's Fastest Battleships" (PDF). Missouri University of Science and Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- Pike, John E. "BB-67 Montana Class". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- SRMN-012: 14th Naval District Combat Intelligence Unit. TS Summaries with Comments by CINCPAC War Plans/Fleet Intelligence Sections, 13 February 1942, RG 457, MHI.

- Toynbee, Summary of International Affairs, 1936, p. 112. W. D. Puleston, The Armed Forces of the Pacific: A Comparison of the Military and Naval Power of the United States and Japan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1941), pp. 208–11. CNO to FDR, 24 March 1938, Navy Department, PSF, FDRL. General Board, "Characteristics of Battleships, 1941 Building Program", 28 June 1939, p. 121, NHC. Secretary to FDR, 14 April 1937, Claude Swanson Folder, Navy Department, PSF, FDRL.

- Friedman, p. 309

- Czarnecki, Joseph (21 August 2002). "What did the USN know about Yamato and when?". NavWeaps.com. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Samuel E. Morison, "The History of United States Naval Operations in World War II," Volumes XII and XIV

- Naval Historical Center. Bureau of Ships' "Spring Styles" Book # 3 (1939–1944) – (Naval Historical Center Lot # S-511) – Battleship Preliminary Design Drawings. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- Friedman, pp. 309–10

- Friedman, pp. 330–32

- Garzke and Dulin, pp. 157–60

- Garzke and Dulin, p. 162

- Friedman, pp. 332–37

- Garzke and Dulin, p. 158

- Friedman, p. 337

- Garzke and Dulin, p. 170

- Garzke and Dulin, pp. 163–64

- Friedman, p. 339

- Friedman, pp. 339–42

- Garzke and Dulin, p. 165

- "CV-59 Forrestal class". Military Analysis Network. Federation of American Scientists. 6 March 1999. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- Friedman, p. 450

- Garzke and Dulin, pp. 171–75

- DiGiulian, Tony (November 2006). "United States of America 16"/50 (40.6 cm) Mark 7". NavWeaps.com. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- DiGiulian, Tony (23 April 2007). "Japanese 46 cm/45 (18.1") Type 94". NavWeapons.com. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- DiGiulian, Tony (3 March 2008). "United States of America 16"/50 (40.6 cm) Mark 7". NavWeapons.com. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- Ballard, Robert D. (1994) [1991]. Exploring the Bismarck. with Rick Archbold (2nd Printing ed.). Italy: Scholastic / Madison Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-590-44269-4.

- Landgraff, R. A.; Locock, Greg. "Do battleships move sideways when they fire?". NavWeaps.com. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- "Mark 7 16-inch/50-caliber gun". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- Mindell, David (2002). Between Human and Machine. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. pp. 262–63. ISBN 0-8018-8057-2.

- Clymer, A. Ben (1993). "The Mechanical Analog Computers of Hannibal Ford and William Newell" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 26 August 2006.

- The 10 Greatest Fighting Ships in Military History. The Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- Ammunition data is taken from Garzke and Dulin, pp. 310–11, 326–27

- Yenne, Bill (2005). "Mega Artillery". Secret Weapons of the Cold War. New York: Berkley Books. pp. 132–33. ISBN 0-425-20149-X.

- "United States of America Experimental and Proposed 5.4" (13.7 cm) and 5" (12.7 cm) Guns 1940s – 1960s". NavWeaps.com. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- "United States of America 20 mm/70 (0.79") Marks 2, 3 & 4". NavWeaps.com. September 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- "United States of America 40 mm/56 (1.57") Mark 1, Mark 2 and M1". NavWeaps.com. November 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Garzke and Dulin, pp. 174–75

- Friedman, Norman (1983). U.S. Aircraft Carriers: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. p. 219. ISBN 0-87021-739-9.

- Garzke and Dulin, p. 171

- "Iowa Class: Armor Protection". Iowa Class Preservation Society. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- Garzke and Dulin, p. 173

- Garzke and Dulin, pp. 173–74

- Jurens, W.J.; Morss, Strafford (2016). "The Washington Naval Treaty and the Armor and Protective Plating of USS Massachusetts". Warship International. Vol. 53, no. 4. Toledo, OH: International Naval Research Organization. pp. 289–94.

- Garzke and Dulin, pp. 168–69

- "Oregon II (Battleship No. 3)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Iowa Class: Shipboard Aircraft". Iowa Class Preservation Association. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2007.

- Bridgeman, Leonard. "The Curtiss Seahawk." Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London: Studio, 1946. p. 221–22. ISBN 1 85170 493 0.

- "Montana (BB-67)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Montana (BB 67)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy, Naval Sea Systems Command. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- "Ohio III (Battleship No. 12)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Ohio (BB 68)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy, Naval Sea Systems Command. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- "Maine II (Battleship No. 10)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Maine (BB 69)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy, Naval Sea Systems Command. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- "New Hampshire II (Battleship No. 25)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "New Hampshire (BB 70)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy, Naval Sea Systems Command. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- "Louisiana III (Battleship No. 19)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Louisiana (BB 71)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy, Naval Sea Systems Command. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- "Kentucky III (SSBN-737)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Wisconsin (BB 64)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy, Naval Sea Systems Command. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- "Missouri (BB 63)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy, Naval Sea Systems Command. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

Further reading

- Garzke, William H. & Dulin, Robert O. Jr. (1995). Battleships: United States Battleships 1935–1992 (Rev. and updated ed.). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-099-0. OCLC 29387525.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-715-1.

- Keegan, John; Ellis, Chris; Natkiel, Richard (2001). World War II: A Visual Encyclopedia. PRC Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85585-878-9.

- Muir, Malcolm Jr. (October 1990). "Rearming in a Vacuum: United States Navy Intelligence and the Japanese Capital Ship Threat, 1936–1945". The Journal of Military History, Vol. 54, No. 4.

- Naval Historical Foundation [2000] (2004). The Navy. New York: Barnes & Noble Inc. ISBN 0-7607-6218-X.

- Newhart, Max R. (May 2007) [1995]. American Battleships: A Pictorial History of BB-1 to BB-71 with prototypes Maine & Texas (Battleship Memorial ed.). Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. pp. 102–106. ISBN 978-1-57510-004-3.

- Wright, Christopher C. (1982). "Question 7/81". Warship International. XIX (2): 198–202. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Wright, Christopher C. (March 2021). "Question 1/58: Concerning the Apparent Omission of an Armor Backing Compound Behind the Main Armor Belt on the Design for the USS Montana (BB-67) Class Battleships". Warship International. LVIII (1): 27–36. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Wright, Christopher C. (June 2021). "Question 1/58: Concerning Cement Backing for Armor on Montana (BB-67) Class Battleships". Warship International. LVIII (2): 118–120. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Wright, Christopher C. (June 2021). "Question 9/58: Concerning Alternative Designs to the Montana (BB-67) Class". Warship International. LVIII (2): 116–118. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Wright, Christopher C. (September 2021). "Question 9/58: Concerning Alternative Designs to the Montana (BB-67) Class". Warship International. LVIII (3): 185–192. ISSN 0043-0374.