United Airlines Flight 175

United Airlines Flight 175 was a domestic passenger flight that was hijacked by five al-Qaeda terrorists on September 11, 2001, as part of the September 11 attacks. The flight's scheduled plan was from Logan International Airport, in Boston, Massachusetts, to Los Angeles International Airport, in Los Angeles, California. The Boeing 767-200 aircraft was deliberately crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center in New York City, killing all 65 people aboard and an unknown number in the building's impact zone.

UA 175's path from Boston to New York City on September 11, 2001 | |

| Hijacking | |

|---|---|

| Date | Tuesday, September 11, 2001 |

| Summary | Terrorist suicide hijacking |

| Site | South Tower (WTC 2) of the World Trade Center, New York City, U.S. 40°42′38.8″N 74°00′47.3″W |

| Total fatalities | c. 679 (2,763 combined with AA 11) |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 767-200 |

| Operator | United Airlines |

| IATA flight No. | UA175 |

| ICAO flight No. | UAL175 |

| Call sign | UNITED 175 |

| Registration | N612UA |

| Flight origin | Logan International Airport, Boston |

| Destination | Los Angeles International Airport |

| Occupants | 65 (including 5 hijackers) |

| Passengers | 56 (including 5 hijackers) |

| Crew | 9 |

| Fatalities | 65 (including 5 hijackers) |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Ground casualties | |

| Ground fatalities | c. 614 (including emergency workers) at the South Tower of the World Trade Center in crash and subsequent collapse |

28 minutes into the flight, the hijackers forcibly breached the cockpit, murdered Captain Victor Saracini and First Officer Michael Horrocks, and forced the remaining passengers and crew to the rear of the aircraft. Lead hijacker Marwan al-Shehhi, who had trained as a pilot in preparation for the attacks, took control of the plane. Unlike Flight 11, whose transponder was turned off, Flight 175's transponder was visible on New York Center's radar, which depicted the aircraft's deviation from its assigned flight path for four minutes before air traffic controllers took notice at 08:51 EDT. Thereafter, they made several unsuccessful attempts to contact the cockpit. Several passengers and crew members aboard made phone calls to family members and relayed information regarding the hijackers and casualties suffered by passengers and crew.

The aircraft crashed into Tower Two (the South Tower) of the World Trade Center at 09:03. The Flight 175 hijacking was coordinated with that of American Airlines Flight 11, which struck the upper floors of Tower One (the North Tower) 17 minutes earlier. The crash of Flight 175 into the South Tower was the only impact televised live around the world. The crash and subsequent fire caused the South Tower to collapse 56 minutes later at 09:59, resulting in hundreds of additional casualties. During the recovery effort at the World Trade Center site, workers uncovered and identified remains from some Flight 175 victims, but many victims have not been identified.

Background

Attacks

The flight was hijacked as part of the September 11 attacks. The team was assembled by al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, who also provided the financial and logistical support, and was led by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed who devised the plot. Bin Laden and Mohammed, along with the hijackers, were motivated by anti-US sentiment. The attacks were given the go ahead by bin Laden in late 1998 or early 1999. The World Trade Center was chosen as one of the targets due to it being a prominent American symbol that represented economic prowess.[1]

Hijackers

The team of hijackers on United Airlines Flight 175 was led by Marwan al-Shehhi, originally from the United Arab Emirates with a stint in Hamburg, Germany as a student. By January 2001, the pilot hijackers had completed their training; Shehhi obtained a commercial pilot licence while training in South Florida,[1] along with American Airlines Flight 11 hijacker Mohamed Atta and Flight 93 hijacker Ziad Jarrah. The hijackers on Flight 175 included Fayez Banihammad, also from the UAE, and three Saudis: brothers Hamza al-Ghamdi and Ahmed al-Ghamdi, as well as Mohand al-Shehri.[2][3]

The hijackers were trained at an al-Qaeda camp called Mes Aynak in Kabul, Afghanistan, where they learned about weapons and explosives, followed by training in Karachi, Pakistan, where they learned about "Western culture and travel". Afterwards, they went to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia for exercises in airport security and surveillance. Part of the training in Malaysia included boarding flights operated by US carriers so they could observe pre-boarding security screenings, flight crew movements around the cabin, and the timing of cabin services.[1][4]

A month before the attacks, Marwan al-Shehhi purchased two four-inch (10 cm) pocket knives from a Sports Authority store in Boynton Beach, Florida, while Banihammad bought a two-piece "snap" utility knife set at a Wal-Mart, and Hamza al-Ghamdi bought a Leatherman Wave multi-tool.[2][3] The hijackers arrived in Boston from Florida between September 7 and 9.[5]

Flight

The flight was operated by a Boeing 767-200, registration number N612UA, built and delivered to United Airlines in February 1983,[6][7] with capacity of 168 passengers (10 in first class, 32 in business class, and 126 in economy class). On the day of the attacks, the flight carried only 56 passengers and 9 crew, which represented a 33 percent load factor – well below the average load factor of 49 percent in the three months preceding September 11.[3] The youngest person on Flight 175 was Christine Hanson, aged two and a half,[8] and the oldest was 82-year-old Dorothy DeAraujo of Long Beach, California.[9] Among the other passengers were hockey scout Garnett Bailey, and former athlete Mark Bavis.

The nine crew members included Captain Victor Saracini (51), First Officer Michael Horrocks (38),[10][11] purser Kathryn Laborie,[12] and flight attendants Robert Fangman, Amy Jarret, Amy King, Alfred Marchand, Michael Tarrou, and Alicia Titus.[13]

Boarding

Hamza al-Ghamdi and Ahmed al-Ghamdi checked out of their hotel and called a taxi to take them to Logan International Airport in Boston, Massachusetts.[14] They arrived at the United Airlines counter in Terminal C at 06:20 Eastern Time and Ahmed al-Ghamdi checked two bags. Both hijackers indicated they wanted to purchase tickets, even though they already had paper tickets, which were purchased approximately 2 weeks before the attacks.[1] They had trouble answering the standard security questions, so the counter agent repeated the questions very slowly until satisfied with their responses.[3][15] Hijacker pilot Marwan al-Shehhi checked a single bag at 06:45, and the other remaining hijackers, Fayez Banihammad and Mohand al-Shehri, checked in at 06:53; Banihammad checked two bags.[3] None of the Flight 175 hijackers were selected for extra scrutiny by the Computer Assisted Passenger Prescreening System (CAPPS).[16]

Shehhi and the other hijackers boarded Flight 175 between 07:23 and 07:28. Banihammad boarded first and sat in first class seat 2A, while Mohand al-Shehri was in seat 2B. At 07:27, Shehhi and Ahmed al-Ghamdi boarded and sat in business class seats 6C and 9D, respectively. One minute later, Hamza al-Ghamdi boarded and sat in 9C.[3][16]

The flight was scheduled to depart at 08:00 for Los Angeles. Fifty-one passengers and the five hijackers boarded the 767 through Terminal C's Gate 19. The plane pushed back at 07:58 and took off at 08:14 from Runway 9,[3][17] about the same time Flight 11 was hijacked. By 08:33, the aircraft reached cruising altitude of 31,000 feet (9,400 m), which is the point when cabin service would normally begin.[3] At 08:37, air traffic controllers asked the pilots of Flight 175 whether they could see American Airlines Flight 11. The crew first responded saying they could not locate the hijacked plane but would continue looking. They then responded that Flight 11 was at 29,000 feet (8,800 m), and controllers instructed Flight 175 to turn and avoid the aircraft.[18] The pilots declared that they had heard a suspicious transmission from Flight 11 upon takeoff. "Sounds like someone keyed the mic and said 'Everyone, stay in your seats'," the flight crew reported. This was the last transmission from Flight 175.[19][17]

Hijacking

Flight 175 was hijacked between 08:42 and 08:46, while Flight 11 was just minutes away from hitting the North Tower.[3] It is believed that hijackers Banihammad and al-Shehri forcibly entered the cockpit and attacked the pilots while the al-Ghamdis commanded passengers and crew to the aft of the cabin and al-Shehhi took over the controls.[17][20] Knives were used to stab the flight crew and kill both pilots.[1][17] One passenger also reported, during a phone call, the use of mace and bomb threats.[17] The first operational evidence that something was abnormal on Flight 175 came at 08:47, when the plane's transponder signal changed twice within the span of one minute, and the aircraft began deviating from its assigned course.[17][20] However, the air traffic controller in charge of the flight did not notice until minutes later at 08:51.[3] Unlike Flight 11, which had turned its transponder off, Flight 175's flight data could still be properly monitored.[20] Also, at 08:51, Flight 175 changed altitude. Over the next three minutes, the controller made five unsuccessful attempts to contact Flight 175 and worked to move other aircraft in the vicinity away from Flight 175.[3]

Near-collisions

Around this time, the flight had a near midair collision with Delta Air Lines Flight 2315 flying from Hartford to Tampa, reportedly missing the plane by only 300 feet (90 m).[21][22] Dave Bottiglia, the controller who was working with the pilot of the Delta, yelled at the pilot to take evasive actions, adding "We have an airplane that we don't know what he's doing. Any action at all."[21][22] Moments before Flight 175 crashed, it avoided another near collision with Midwest Express Flight 7, which was flying from Milwaukee to New York.[23]

At 08:55 a supervisor at the New York Air Traffic Control Center notified the center's operations manager of the Flight 175 hijacking. Bottiglia – who was handling both Flight 11 and Flight 175 – remarked, "We might have a hijack over here, two of them."[3] At 08:58, Flight 175 was over New Jersey at 28,500 feet, heading toward New York City. In the five minutes from approximately 08:58 when Shehhi completed the final turn toward New York City until the moment of impact, the plane was in a sustained power dive, descending more than 24,000 feet in 5 minutes 4 seconds, at an average rate of over 5,000 feet per minute.[20] Bottiglia reported he and his colleagues "were counting down the altitudes, and they were descending, right at the end, at 10,000 feet per minute. That is absolutely unheard of for a commercial jet."[22]

Calls

Flight attendant Robert Fangman and passengers Peter Hanson and Brian David Sweeney made phone calls from GTE airphones in the rear of the aircraft. Airphone records also indicate that passenger Garnet Bailey made four phone call attempts to his wife.[24][25]

At 08:52, a male flight attendant – likely Fangman – called a United Airlines maintenance office in San Francisco and spoke with Marc Policastro.[17][26] Fangman reported the hijacking and said the hijackers were likely flying the plane. He also said both pilots were dead and that a flight attendant had been stabbed.[17] After a minute and 15 seconds, Fangman's call was disconnected.[24] Policastro subsequently made attempts to contact the aircraft's cockpit using the Aircraft Communication Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) message system. He wrote, "I heard of a reported incident aboard your acft [aircraft]. Plz verify all is normal." He received no reply.[3]

Brian David Sweeney tried to call his wife, Julie, at 08:59, but ended up leaving a message, telling her the plane had been hijacked. He then called his parents at 09:00 and spoke with his mother, Louise. Sweeney told his mother about the hijacking and mentioned that passengers were considering storming the cockpit and taking control of the aircraft.[17] Sweeney said he thought the hijackers might come back, so he might have to hang up quickly. He then said goodbye to his mother as he quickly hung up.[27]

At 08:52, Peter Hanson called his father, Lee Hanson, in Easton, Connecticut, telling him of the hijacking. Hanson was traveling with his wife, Sue, and their two-year-old daughter, Christine, the youngest victim of the September 11 attacks. The family was originally seated in Row 19, in seats C, D, and E; however, Peter placed the call to his father from seat 30E. Speaking softly, Hanson said the hijackers had commandeered the cockpit, a flight attendant had been stabbed, and that possibly someone else in the front of the aircraft had been killed. He also said the plane was flying erratically. Hanson asked his father to contact United Airlines, but Lee could not get through and instead called the police.[17][28]

Peter Hanson made a second phone call to his father at 09:00:

It's getting bad, Dad. A stewardess was stabbed. They seem to have knives and Mace. They said they have a bomb. It's getting very bad on the plane. Passengers are throwing up and getting sick. The plane is making jerky movements. I don't think the pilot is flying the plane. I think we are going down. I think they intend to go to Chicago or someplace and fly into a building. Don't worry, Dad. If it happens, it'll be very fast ... Oh, my God ... oh, my God, oh, my God.[22]

As the call abruptly ended, Hanson's father heard a woman screaming.[22]

Crash

.svg.png.webp)

As the plane approached New York City, Shehhi would have seen the fire and smoke pouring from the North Tower in the distance.[29] The aircraft was in a banking left turn in its final moments, as it appeared the plane might have otherwise missed the building or merely scraped it with a wing. Therefore, those who were on the left side of the plane would also have had a clear view of the towers approaching, with one burning.[22] At 09:01, two minutes before impact as Flight 175 continued its descent into Lower Manhattan, the New York Center alerted another nearby Air Traffic Facility responsible for low-flying aircraft, which was able to monitor the aircraft's path over New Jersey, and then over Staten Island and Upper New York Bay in its final moments.[20]

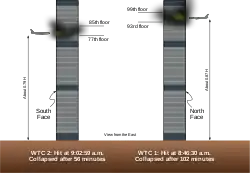

At 09:03,[lower-alpha 1] Flight 175 crashed nose-first into the southern façade of the South Tower of the World Trade Center at over 500 miles per hour (800 km/h; 220 m/s; 430 kn),[lower-alpha 2] striking through floors 77 and 85[35][36] with approximately 9,100 U.S. gallons (34,000 L; 7,600 imp gal) of jet fuel on board.[37]

By the time Flight 175 struck the South Tower, multiple media organizations were already covering the crash of Flight 11, which had hit the North Tower 17 minutes earlier. The image of Flight 175's crash was thus caught on video from multiple vantage points on live television and amateur video, while approximately a hundred cameras captured Flight 175 in photographs before it crashed.[38] Video footage of the crash was replayed numerous times in news broadcasts on the day of the attacks and in the following days, before major news networks put restrictions on use of the footage.[39]

After the plane penetrated through the tower, part of the plane's landing gear and fuselage came out the north side of the tower and crashed through the roof and two of the floors of 45–47 Park Place, between West Broadway and Church Street, 600 feet (200 yd; 180 m) north of the former World Trade Center. Three floor beams of the top floor of the building were destroyed, causing major structural damage.[33][40][41][42]

Collapse

Unlike at the North Tower, one of the three stairwells (A) was still intact after Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower. This was because the plane struck the tower offset from the center and not centrally as Flight 11 in the North Tower had done.[36][43] Only 18 people passed the impact zone through the available stairway and left the South Tower safely before it collapsed. Only one person on the 81st floor survived: Stanley Praimnath, whose office was sliced by the wing of the plane. He witnessed Flight 175 coming toward him.[44][45] One of the wings sliced through his office and wound up wedged in a doorway about twenty feet (six meters) away from him. No one escaped above the impact point in the North Tower.[43]

An unknown number of people were killed instantly at the moment of impact; the remaining survivors of the initial crash died from smoke inhalation, fires, or the eventual collapse, while a very small number of people were spotted jumping or falling from the upper floors of the South Tower. Some people above the impact zone made their way upward toward the roof in hopes of a helicopter rescue. However, access doors to the roof were locked; in any case, thick smoke and intense heat prevented rescue helicopters from landing.[46][47]

Flight 175's crash into the South Tower was faster and lower down than that of the North Tower, compromising its structural integrity more. With 25 floors above the South Tower's impact zone compared to the North Tower's 11, there was far more structural weight pressing down on a damaged section of the building on fire.[48] The South Tower collapsed at 09:59:00, after burning for 56 minutes,[49][50] being the first of the two skyscrapers to collapse despite being the second to be hit, and only burning for around half the amount of time as the North Tower did before it too fell.

Aftermath

The flight recorder for Flight 175, as with Flight 11's, was never found.[51] Some debris from Flight 175 was recovered nearby, including landing gear found on top of a building on the corner of West Broadway and Park Place, an engine found at Church and Murray Street, and a section of the fuselage which landed on top of 5 World Trade Center.[52][53] In April 2013, a piece of the inboard wing flap mechanism from a Boeing 767[54] was discovered wedged between two buildings at Park Place.[55]

During the recovery process, small fragments were identified from some passengers on Flight 175, including a 6 in (150 mm) piece of bone belonging to Peter Hanson,[56] and small bone fragments of Lisa Frost.[57] In 2008, the remains of Flight 175 passenger Alona Abraham were identified using DNA samples.[58] Remains of many others aboard Flight 175 were never recovered.[59]

Shortly after September 11, the number for future flights on the same route was changed from 175 to 1525.[60] Since then, United Airlines has renumbered and rescheduled all flights from Boston to Los Angeles. United Airlines Flight 311[61] now operates the Boston to LAX route, leaving at 08:30 and is operated by a Boeing 737 MAX 9. It was reported in May 2011 that United was reactivating flight numbers 175 and 93 as a codeshare operated by Continental, sparking an outcry from some in the media and the labor union representing United pilots.[62][63][64] However, United said the reactivation was a mistake and said the numbers were "inadvertently reinstated", and would not be reactivated.[63]

The names of the victims of Flight 175 are inscribed at the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.[65]

The federal government provided financial aid – a minimum of $500,000 – for the families of victims who died in the attack. Individuals who accepted funds from the government were required to forfeit their ability to sue any entity for damages.[66] More than $7 billion has been paid out to victims by the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, although that figure includes damages to those who were injured or killed on the other hijacked flights or the towers.[67] In total, lawsuits were filed on behalf of 96 people against the airline and associated companies. The vast majority were settled under terms that were not made public, but the total compensation is estimated to be around $500 million.[68][67] Only one lawsuit progressed to a civil trial; a wrongful death filing by the family of Mark Bavis against the airline, Boeing, and the airport's security company.[67] This was eventually settled in September 2011.[68] US President George Bush, other top officials, and various government agencies were also sued by the widow of a passenger, Ellen Mariani.[69][70][71] Mariani's cases were deemed to be frivolous.[72]

A piece of fuselage on the roof of 5 World Trade Center

A piece of fuselage on the roof of 5 World Trade Center Airplane engine parts from Flight 175

Airplane engine parts from Flight 175 Panel S-2 of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum's South Pool, one of three on which the names of victims from Flight 175 are inscribed

Panel S-2 of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum's South Pool, one of three on which the names of victims from Flight 175 are inscribed

References

Notes

- The exact time is disputed. The 9/11 Commission report says 9:03:11,[17][30] NIST reports 9:02:59,[31] some other sources report 9:03:02.[32]

- Sources disagree on the exact speed of impact. NTSB study in 2002 concluded around 515 mph (448 kn; 230 m/s; 829 km/h),[33] whereas MIT study concluded 503 mph (437 kn; 225 m/s; 810 km/h).[34]

Citations

- Shane 2009.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation 2008, p. 218.

- 9/11 Commission 2004b.

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, pp. 156–158.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation 2008, p. 261.

- "N612UA United Airlines Boeing 767-200". www.planespotters.net. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- "Brief of Accident". National Transportation Safety Board. March 7, 2006. DCA01MA063. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2007. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- Hirschkorn, Phil (April 11, 2006). "Father recalls son's last words on 9/11". CNN. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- Wilson, Mike (September 10, 2005). "Lisa Frost, A Recent College Graduate, Was on Her Way to California to Visit Her Family L". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- Burke, Susan. "Four Pilot Lights – Nothing Could Extinguish their Flames". Air Line Pilots Association. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- Kropf, Schuyler. "C of C track athlete lost her dad, a co-pilot, during 9/11". Post and Courier. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- Hanson, Fred. "Braintree man will push airline drink cart from Boston to Ground Zero in memory of 9/11". The Patriot Ledger. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- "United Airlines Flight 175". CNN. 2001. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation 2008, p. 288.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (September 21, 2001). "Interview with Gail Jawahir" (PDF). Intelfiles. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, p. 2.

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, pp. 7–8.

- Ellison, Michael (October 17, 2001). "'We have planes. Stay quiet' – Then silence". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- Wald, Matthew L.; Sack, Kevin (October 16, 2001). "A Nation Challenged: The Tapes; 'We Have Some Planes,' Hijacker Said on Sept. 11". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- NTSB 2002a.

- "Report: hijacked plane nearly hit flight from Bradley". SouthCoastToday.com. September 12, 2002. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- "Flight 175: As the World Watched (TLC documentary)". The Learning Channel. December 2005. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013.

- Spencer, Lynn (2008). Touching History: The Untold Story of the Drama That Unfolded in the Skies Over America on 9/11. Simon and Schuster. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-1416559252.

- "Exhibit #P200018, United States v. Zacarias Moussaoui". United States District Court, Eastern District of Virginia. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- "The Four Flights – Staff Statement No. 4" (PDF). 9/11 Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 16, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- Davidsson 2013, p. 173.

- "Widow: 9/11 passengers planned to resist". edition.cnn.com. March 10, 2004. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- Serrano, Richard A. (April 11, 2006). "Moussaoui Jury Hears the Panic From 9/11". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2008.

- McMillan, Tom (2014). Flight 93: The Story, the Aftermath, and the Legacy of American Courage on 9/11. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 73. ISBN 978-1442232853. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- 9/11 Commission 2004b, p. 24.

- NIST 2005, p. 27.

- "Timeline for United Airlines Flight 175". NPR. June 17, 2004. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- NTSB 2002b.

- Kausel, Eduardo. "Speed of Aircraft" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- Weiss, Dick (September 11, 2011). "Touching 9/11 tribute to Welles Crowther, selfless hero, before Central Florida-Boston College game". NY Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, p. 293.

- NIST 2005, p. 38.

- Boxer, Sarah (September 11, 2002). "One Camera, Then Thousands, Indelibly Etching a Day of Loss". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- Bauder, David (August 21, 2002). "The violent images of 9-11 will return to television screens, but to what extent?". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Klersfeld, Noah; Nordenson, Guy; and Associates, LZA Technology (2003). World Trade Center emergency damage assessment of buildings: Structural Engineers Association of New York inspections of September and October 2001. Vol. 1. Structural Engineers Association of New York. Archived from the original on September 7, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- Noah, Klersfeld; Nordenson, Guy; Associates, and; (Firm), L.Z.A. Technology (January 3, 2008). World Trade Center emergency damage ... Structural Engineers Association of New York. Archived from the original on September 7, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- Corley, Gene; Federal Insurance And Mitigation Administration, United States; Region Ii, United States. Federal Emergency Management Agency; O'Mara, Greenhorne (May 2002). World Trade Center building ... ISBN 978-0160673894. Archived from the original on September 7, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- Dwyer, Jim; Lipton, Eric; et al. (May 26, 2002). "102 Minutes: Last Words at the Trade Center; Fighting to Live as the Towers Die". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, p. 294.

- "Flight 175: As the World Watched (TLC documentary)". The Learning Channel. December 2005. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013.

- Paltrow, Scot J.; Sook, Queena (October 23, 2001). "Could Helicopters Have Saved People From the Top of the Trade Center?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, p. 279.

- "A NATION CHALLENGED: THE TRADE CENTER CRASHES; First Tower to Fall Was Hit At Higher Speed, Study Finds". The New York Times. February 23, 2002. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - NIST 2005, pp. 44, 148.

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, p. 305.

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, p. 456.

- NISTb 2005.

- Blumenthal, Ralph; Mowjood, Sharaf (December 8, 2009). "Muslim Prayers and Renewal Near Ground Zero". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- Goodman, J. David (April 29, 2013). "Jet Debris Near 9/11 Site Is Identified as Wing Part". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- Goldstein, Joseph (April 26, 2013). "11 Years Later, Debris From Plane Is Found Near Ground Zero". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- Gordon, Greg (April 11, 2006). "Moussaoui jurors hear 9/11 victims' final calls". Star Tribune. Minneapolis.

- Radcliffe, Jim (May 20, 2005). "Her parents now have the 9/11 victim's cremated remains with them in Orange County". Orange County Register.

- Hadad, Shmulik (January 31, 2008). "September 11 victim laid to rest". Ynetnews.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- Vogel, Charity (August 21, 2003). "Adding to Grief; Families of Many Victims of the World Trade Center Attack Deal With the Prospect of Never Having Their Remains Identified". Buffalo News.

- "Logan Airport bears memory of its fateful role with silence". The Boston Globe. September 12, 2002. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- "United Airlines Worldwide Timetable". united.com. United Airlines. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- Mutzabaugh, Ben (May 18, 2011). "Unions slam United for mistakenly reinstating 9/11 flight numbers". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- Romero, Frances (May 18, 2011). "Flight Number Flub: United/Continental Accidentally Reinstates Flights 93 and 175". Time. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- McCartney, Scott (May 18, 2011). "Bad Mistake: United Revives Sept. 11 Flight Numbers". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- About: The Memorial Names Layout Archived July 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Memorial Guide: National 9/11 Memorial. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- "Homefront: Details of Sept. 11 Victims Payments". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- Moynihan, Colin (October 21, 2010). "Timetable Is Set for the Only Civil Trial in a 9/11 Death". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- Weiser, Benjamin (September 19, 2011). "Family and United Airlines Settle Last 9/11 Wrongful-Death Lawsuit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- "New Hampshire woman sues Bush, top officials, over 9-11". Triblive. The Associated Press. September 24, 2003. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- "Sept. 11 widow sues United Airlines". CNN. December 20, 2001. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- "United Is Sued by Wife of a Man Who Died in Trade Center Attack". The Wall Street Journal. December 20, 2001. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- Weiser, Benjamin (May 16, 2013). "Court Penalizes a Lawyer Over Slurs in a 9/11 Filing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

Sources

- Shane, J.M. (2009). "September 11 Terrorist Attacks Against the United States and the Law Enforcement Response". In Haberfeld, M.R.; von Hassell, Agostino (eds.). A New Understanding of Terrorism: Case Studies, Trajectories and Lessons Learned. pp. 99–142. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0115-6_7. ISBN 978-1441901149.

- Final Report of the 9/11 Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (PDF) (Report). National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. July 22, 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- Staff Report of the 9/11 Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States (PDF) (Report). National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. September 2005 [August 26, 2004]. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- "Hijackers' Timeline". vault.fbi.gov. Federal Bureau of Investigation. February 4, 2008. Archived from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- "Flight Path Study – United Airlines Flight 175" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. February 19, 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- "Radar Data Impact Speed Study" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. February 7, 2002. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 19, 2007. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- National Construction Safety Team (September 2005). Final Report on the Collapse of the World Trade Center Towers (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology (Report). United States Department of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- Building and Fire Research Laboratory (September 2005). Visual Evidence, Damage Estimates, and Timeline Analysis (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology (Report). United States Department of Commerce. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- Davidsson, Elias (2013). Hijacking America's Mind On 9/11: Counterfeiting Evidence. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0875869742.

External links

- The Final 9/11 Commission Report (Archive)

- CNN September 11 Memorial page, with passenger and crew lists (Archive)

- Government Releases Detailed Information on 9/11 Crashes

- Picture of aircraft Pre 9/11

- September 11, 2001 archive of United Airlines site with condolences for deceased (Archive)

- Page with additional information, from September 12, 2001 (Archive)