Wallonia

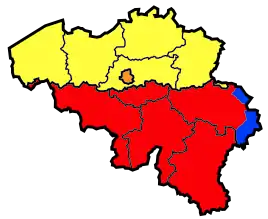

Wallonia (/wɒˈloʊniə/; French: Wallonie [walɔni])[4] is one of the three regions of Belgium—along with Flanders and Brussels.[5] Covering the southern portion of the country, Wallonia is primarily French-speaking. It accounts for 55% of Belgium's territory, but only a third of its population. The Walloon Region and the French Community of Belgium, which is the political entity responsible for matters related mainly to culture and education, are independent concepts, because the French Community of Belgium encompasses both Wallonia and the bilingual Brussels-Capital Region.

Wallonia

| |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Anthem: Le Chant des Wallons ("The song of the Walloons") | |

| |

| |

| Coordinates: 50°30′0'N, 4°45′ 0″ E | |

| Country | |

| Community |

|

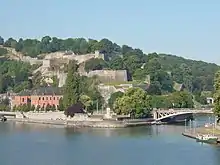

| Capital | Namur |

| Government | |

| • Executive | Government of Wallonia |

| • Governing parties (2019) | PS, MR, Ecolo |

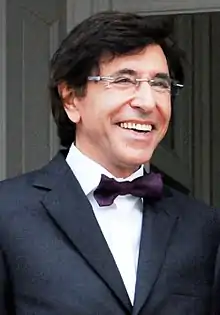

| • Minister-President | Elio Di Rupo (PS) |

| • Legislature | Parliament of Wallonia |

| • Speaker | Jean-Claude Marcourt (PS) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 16,845 km2 (6,504 sq mi) |

| Population (1 January 2019)[2] | |

| • Total | 3,633,795 |

| • Density | 220/km2 (560/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Walloons |

| Demographics | |

| • Languages | French German (in the German-speaking Community of Belgium) Dutch (in municipalities with language facilities)[3] Walloon |

| ISO 3166 code | BE-WAL |

| Celebration Day | Third Sunday of September |

| Most populous city | Charleroi |

| Website | www.wallonie.be |

There is a German-speaking minority in eastern Wallonia, resulting from the annexation of three cantons previously part of the German Empire at the conclusion of World War I. This community represents less than 1%[6] of the Belgian population. It forms the German-speaking Community of Belgium, which has its own government and parliament for culture-related issues.

During the industrial revolution, Wallonia was second only to the United Kingdom in industrialization, capitalizing on its extensive deposits of coal and iron. This brought the region wealth, and from the beginning of the 19th to the middle of the 20th century, Wallonia was the more prosperous half of Belgium. Since World War II, the importance of heavy industry has greatly diminished, and the Flemish Region has exceeded Wallonia in wealth as Wallonia has declined economically. Wallonia now suffers from high unemployment and has a significantly lower GDP per capita than Flanders. The economic inequalities and linguistic divide between the two are major sources of political conflicts in Belgium and a major factor in Flemish separatism.

The capital of Wallonia is Namur, and the most populous city is Charleroi. Most of Wallonia's major cities and two-thirds of its population lie along the east–west aligned Sambre and Meuse valley, the former industrial backbone of Belgium. To the north of this valley, Wallonia lies on the Central Belgian Plateau, which, like Flanders, is a relatively flat and agriculturally fertile area. The south and southeast of Wallonia is made up of the Ardennes, an expanse of forested highland that is less densely populated.

Wallonia borders Flanders and the Netherlands (the province of Limburg) in the north, France (Grand Est and Hauts-de-France) to the south and west, and Germany (North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate) and Luxembourg (Capellen, Clervaux, Esch-sur-Alzette, Redange and Wiltz) to the east. Wallonia has been a member of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie since 1980.

Terminology

The term "Wallonia" can mean slightly different things in different contexts. One of the three federal regions of Belgium is still constitutionally defined as the "Walloon Region" as opposed to "Wallonia", but the regional government has renamed itself Wallonia, and it is commonly called Wallonia.[7][8] Preceding 1 April 2010, when the renaming came into effect, Wallonia would sometimes refer to the territory governed by the Walloon Region, whereas Walloon Region referred specifically to the government. In practice, the difference between the two terms is small and what is meant is usually clear, based on context.

Wallonia is a cognate of terms such as Wales, Cornwall and Wallachia,[9][10][11] ultimately also related to words Celt and Belgae, phonetically evolved over centuries.[12] The Germanic word Walha, meaning the strangers, referred to Gallic or Celtic people. Wallonia is named after the Walloons, a group of locals who natively speak Romance languages. In Middle Dutch (and French), the term Walloons included both historical secular Walloon principalities, as well as the French-speaking population of the Prince-Bishopric of Liège[13] or the whole population of the Romanic sprachraum within the medieval Low Countries.

History

Julius Caesar conquered Gaul in 57 BC. The Low Countries became part of the larger Gallia Belgica province which originally stretched from southwestern Germany to Normandy and the southern part of the Netherlands. The population of this territory was Celtic with a Germanic influence which was stronger in the north than in the south of the province. Gallia Belgica became progressively romanized. The ancestors of the Walloons became Gallo-Romans and were called the "Walha" by their Germanic neighbours. The "Walha" abandoned their Celtic dialects and started to speak Vulgar Latin.[15]

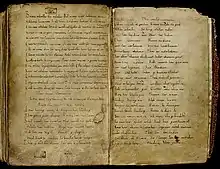

The Merovingian Franks gradually gained control of the region during the 5th century, under Clovis. Due to the fragmentation of the former Roman Empire, Vulgar Latin regionally developed along different lines and evolved into several langue d'oïl dialects, which in Wallonia became Picard, Walloon and Lorrain.[15] The oldest surviving text written in a langue d'oïl, the Sequence of Saint Eulalia, has characteristics of these three languages and was likely written in or very near to what is now Wallonia around 880 AD.[14] From the 4th to the 7th century, the Franks established several settlements, probably mostly in the north of the province where the romanization was less advanced and some Germanic trace was still present. The language border (that now splits Belgium in the middle) began to crystallize between 700 under the reign of the Merovingians and Carolingians and around 1000 after the Ottonian Renaissance.[16] French-speaking cities, with Liège as the largest one, appeared along the Meuse, while Gallo-Roman cities such as Tongeren, Maastricht and Aachen became Germanized.

The Carolingian dynasty dethroned the Merovingians in the 8th century. In 843, the Treaty of Verdun gave the territory of present-day Wallonia to Middle Francia, which would shortly fragment, with the region passing to Lotharingia. On Lotharingia's breakup in 959, the present-day territory of Belgium became part of Lower Lotharingia, which then fragmented into rival principalities and duchies by 1190. Literary Latin, which was taught in schools, lost its hegemony during the 13th century and was replaced by Old French.[15]

In the 15th century, the Dukes of Burgundy took over the Low Countries. The death of Charles the Bold in 1477 raised the issue of succession, and the Liégeois took advantage of this to regain some of their autonomy.[15] From the 16th to the 18th century, the Low Countries were governed successively by the Habsburg dynasty of Spain (from the early 16th century until 1713–14) and later by Austria (until 1794). This territory was enlarged in 1521–22 when Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor gained the Tournai region from France.[15]

Present-day Belgium was conquered in 1795 by the French Republic during the French Revolutionary Wars. It was annexed to the Republic, which later became the Napoleonic Empire. After the Battle of Waterloo, Wallonia became part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands under King William of Orange.[15] The Walloons played an active part in the Belgian Revolution in 1830. The Provisional Government of Belgium proclaimed Belgium's independence and held elections for the National Congress.[15]

Belgian period

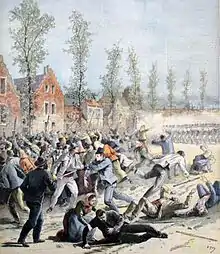

In the 19th century, the area began to industrialize, and Wallonia was the first fully industrialized area in continental Europe.[17] This brought the region great economic prosperity, which was not mirrored in poorer Flanders and the result was a large amount of Flemish immigration to Wallonia. Belgium was divided into two divergent communities. On the one hand, the very Catholic Flemish society was characterized by an economy centered on agriculture; on the other hand, Wallonia was the center of the continental European Industrial Revolution, where classical liberal and socialist movements were rapidly emerging.[18] Major strikes and general strikes took place in Wallonia, including the Walloon jacquerie of 1886, the Belgian general strikes of 1893, 1902, 1913 (for universal suffrage), 1932 (depicted in Misère au Borinage), and 1936. After World War II, major strikes included the general strike against Leopold III of Belgium (1950), and the 1960-1961 Winter General Strike for autonomy for Wallonia.

The profitability of the heavy industries to which Wallonia owed its prosperity started declining in the first half of the 20th century, and the center of industrial activity shifted north to Flanders. The loss of prosperity caused social unrest, and Wallonia sought greater autonomy in order to address its economic problems. In the wake of the 1960-1961 Winter General Strike, the process of state reform in Belgium got underway. This reform started partly with the linguistic laws of 1962–63, which defined the four language areas within the constitution. But the strikes of 1960 which took place in Wallonia more than in Flanders are not principally linked with the four language areas nor with the Communities but with the Regions. In 1968, the conflict between the communities burst out. French speakers in Flanders (who were not necessarily Walloons) were driven out of, most notably the Leuven-based Catholic University amid shouts of "Walen buiten!" ("Walloons out!"). After a formal split of the university in two and the creation of a brand new campus in Wallonia,[18] a wider series of State reforms was passed in Belgium, which resulted in the federalisation of the nation and the creation of the Walloon Region and the French Community (comprising both Wallonia and Brussels), administrative entities each of which would gain various levels of considerable autonomy.

Geography

Wallonia is landlocked, with an area of 16,901 km2 (6,526 sq mi), or 55 percent of the total area of Belgium. The Sambre and Meuse valley, from Liège (70 m (230 ft)) to Charleroi (120 m (390 ft)) is an entrenched river in a fault line which separates Middle Belgium (elevation 100–200 m (330–660 ft)) and High Belgium (200–700 m (660–2,300 ft)). This fault line corresponds to a part of the southern coast of the late London-Brabant Massif. The valley, along with Haine and Vesdre valleys form the sillon industriel, the historical centre of the Belgian coalmining and steelmaking industry, and is also called the Walloon industrial backbone. Due to their long industrial historic record, several segments of the valley have received specific names: Borinage, around Mons, le Centre, around La Louvière, the Pays noir, around Charleroi and the Basse-Sambre, near Namur.

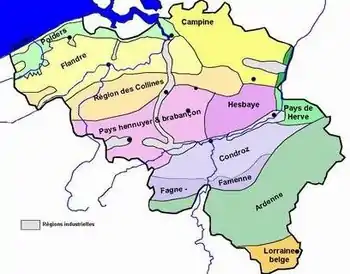

To the north of the Sambre and Meuse valley lies the Central Belgian plateau, which is characterized by intensive agriculture. The Walloon part of this plateau is traditionally divided into several regions: Walloon Brabant around Nivelles, Western Hainaut (French: Wallonie picarde, around Tournai), and Hesbaye around Waremme. South of the sillon industriel, the land is more rugged and is characterized by more extensive farming. It is traditionally divided into the regions of Entre-Sambre-et-Meuse, Condroz, Fagne-Famenne, the Ardennes and Land of Herve, as well as the Belgian Lorraine around Arlon and Virton. Dividing it into Condroz, Famenne, Calestienne, Ardennes (including Thiérache), and Belgian Lorraine (which includes the Gaume) is more reflective of the physical geography. The larger region, the Ardennes, is a thickly forested plateau with caves and small gorges. It is host to much of Belgium's wildlife but little agricultural capacity. This area extends westward into France and eastward to the Eifel in Germany via the High Fens plateau, on which the Signal de Botrange forms the highest point in Belgium at 694 metres (2,277 ft).

Subdivisions

The Walloon region covers 16,901 km2 (6,526 sq mi) and is divided into five provinces, 20 arrondissements and 262 cities or municipalities.

| Province | Capital city | Population (1 January 2019)[2] | Area[1] | Density | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mons (Bergen) | 1,344,241 | 3,813 km2 (1,472 sq mi) | 353/km2 (910/sq mi) | |

| 2 | Liège (Luik) | 1,106,992 | 3,857 km2 (1,489 sq mi) | 288/km2 (750/sq mi) | |

| 3 | Arlon (Aarlen) | 284,638 | 4,459 km2 (1,722 sq mi) | 64/km2 (170/sq mi) | |

| 4 | Namur (Namen) | 494,325 | 3,675 km2 (1,419 sq mi) | 135/km2 (350/sq mi) | |

| 5 | Wavre (Waver) | 403,599 | 1,097 km2 (424 sq mi) | 368/km2 (950/sq mi) | |

The province of Walloon Brabant is the most recent one, being formed in 1995 after the splitting of the province of Brabant.

Cities

The largest cities in Wallonia are:[19]

- Charleroi (204,146)

- Liège (195,790)

- Namur (110,428)

- Mons (92,529)

- La Louvière (81,138)

- Tournai (69,792)

- Seraing (63,500)

- Verviers (56,596)

- Mouscron (55,687)

- Herstal (38,969)

- Braine-l'Alleud (38,748)

- Châtelet (36,131)

The 10 largest groups of foreign residents in 2018 are:

| 98,682 | |

| 81,148 | |

| 16,815 | |

| 16,275 | |

| 16,040 | |

| 14,181 | |

| 11,340 | |

| 9,112 | |

| 7,534 | |

| 6,699 |

Science and technology

Contributions to the development of science and technology have appeared since the beginning of the country's history. The baptismal font of Renier de Huy is not the only example of medieval Walloon technical expertise: the words "houille" (coal)[20] or "houilleur" (coal miner) or "grisou" (damp) were coined in Wallonia and are Walloon in origin.

The economically important very deep coal mining in the course of the First Industrial Revolution has required highly reputed specialized studies for mining engineers. But that was already the case before the Industrial Revolution, with an engineer as Rennequin Sualem for instance.

Engineer Zenobe Gramme invented the Gramme dynamo, the first generator to produce power on a commercial scale for industry. Chemist Ernest Solvay gave his name to the Solvay process for production of soda ash, an important chemical for many industrial uses. Ernest Solvay also acted as a major philanthropist and gave its name to the Solvay Institute of Sociology, the Solvay Brussels School of Economics and Management and the International Solvay Institutes for Physics and Chemistry which are now part of the Université libre de Bruxelles. In 1911, he started a series of conferences, the Solvay Conferences on Physics and Chemistry, which have had a deep impact on the evolution of quantum physics and chemistry.

Georges Lemaître of the Université catholique de Louvain is credited with proposing the Big Bang theory of the origin of the universe in 1927.

Three Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine were awarded to Walloons: Jules Bordet (Université libre de Bruxelles) in 1919, Albert Claude (ULB) together with Christian De Duve (UCLouvain) in 1974.

In the present day, Bureau Greisch has acquired an international reputation as consulting engineer and architect in the fields of structures, civil engineering and buildings, including the Millau Viaduct in France.

Economy

Wallonia is rich in iron and coal, and these resources and related industries have played an important role in its history. In ancient times, the Sambre and Meuse valley was an important industrial area in the Roman Empire. In the Middle Ages, Wallonia became a center for brass working and bronze working, with Huy, Dinant and Chimay being important regional centers. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the iron masters of Liège developed a method of refining iron ore by the use of a blast furnace, called the Walloon Method. There were also a few coal mines around Charleroi and the Borinage during this period, but their output was small, and was principally consumed as fuel by various industries such as the important glassmaking industry that sprang up in the Charleroi basin during the 14th century.[21]

In the 19th century, the area began to industrialize, mainly along the so-called sillon industriel. It was the first fully industrialized area in continental Europe,[17] and Wallonia was the second industrial power in the world, in proportion to its population and its territory, after the United Kingdom.[22] The sole industrial centre in Belgium outside the collieries and blast furnaces of Wallonia was the historic cloth making town of Ghent.[23]

The two World Wars curbed the continuous expansion that Wallonia had enjoyed up till that time. Towards the end of the 1950s, things began to change dramatically. The factories of Wallonia were by then antiquated, the coal was running out and the cost of extracting coal was constantly rising. It was the end of an era, and Wallonia has been making efforts to redefine itself. The restoration of economical development is high on the political agenda, and the government is encouraging development of industries, notably in cutting-edge technology and in business parks.[24] The economy is improving,[25] but Wallonia is not yet at the level of Flanders and is still suffering from difficulties.

%252C_Rue_Arthur_Decoux_(1).jpg.webp)

The current Walloon economy is relatively diversified, although certain areas (especially around Charleroi and Liège) are still suffering from the steel industry crisis, with an unemployment rate of up to 30 percent. Nonetheless, Wallonia has some companies which are world leaders in their specialized fields, including armaments, glass production,[27] lime and limestone production,[28] cyclotrons[29] and aviation parts.[30] The south of Wallonia, bordering Luxembourg, benefits from its neighbour's economic prosperity, with many Belgians working on the other side of the border; they are often called frontaliers. The Ardennes area south of the Meuse is a popular tourist destination for its nature and outdoor sports, in addition to its cultural heritage, with places such as Bastogne, Dinant, Durbuy, and the famous hot springs of Spa.

The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the region was 105.7 billion € in 2018, accounting for 23% of Belgian economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 25,700 € or 85% of the EU27 average in the same year.[31]

Politics and government

Belgium is a federal state made up of three communities and three regions, each with considerable autonomy. One of these is the Walloon Region, which is governed by the Parliament of Wallonia and the executive Government of Wallonia. The Walloon Region's autonomy extends even to foreign policy; Wallonia is entitled to pursue its own foreign policy, including the signing of treaties, and in many domains, even the Belgian federal government is not able to sign an international treaty without the agreement of the Parliament of Wallonia.

Wallonia is also home to about 80 percent of the population of the French Community of Belgium, a political level responsible for matters related mainly to culture and education, with the remainder living in Brussels. Wallonia is also home to the small German-speaking Community of Belgium in the east, which has its own government and parliament for culture-related issues. Although in Flanders, the Flemish Region assigned all of its powers to the Flemish Community, the Walloon Region remains in principle distinct from and independent from the French Community, and vice versa. Despite this, the French Community's parliament is almost entirely composed of members of Wallonia's and Brussels' parliaments, so the bodies are governed by the same individuals. Additionally, the French Community of Belgium has controversially begun referring to itself exclusively as the 'Wallonia-Brussels Federation' to emphasize the links between the French Community, Wallonia and Brussels.

The Walloon Region has a unicameral parliament with 75 members elected for five years by direct universal suffrage, and an executive, the Government of Wallonia, elected by a political majority in Parliament. The Government numbers nine members with the president. Each member is called a Walloon minister. The head of the Government is called the Minister-President of Wallonia. The coalition government for the 2014–2019 legislature was a center-left coalition PS-cdH until July 28 when it was replaced by a center-left coalition MR-cdH. The current Minister-President is Elio Di Rupo.

History of Walloon autonomy

"From 1831, the year of Belgium's independence, until the federalization of the country in 1970, Wallonia has increasingly asserted itself as a region in its own right."[32] Following several state reforms, especially the 1993 state reform, Belgium became a federal state made up of three communities and three regions, with Wallonia being represented by the Walloon Region and its two language communities. The directly elected Walloon Parliament was created in June 1995, replacing the Conseil régional wallon (Regional Council of Wallonia). The first Council had sat on 15 October 1980 and was composed of members of the Belgian Chamber of Representatives and the Belgian Senate elected in Wallonia.

Symbols

The first appearance of the French word Wallonie as a reference to the romance world as opposed to Germany is said to date from 1842.[33] Two years later, it was first used to refer to the Romance part of the young country of Belgium.[34] In 1886, the writer and Walloon militant Albert Mockel, first used the word with a political meaning of cultural and regional affirmation,[35] in opposition with the word Flanders used by the Flemish Movement. The word had previously appeared in German and Latin as early as the 17th century.[36]

The rising of a Walloon identity led the Walloon Movement to choose different symbols representing Wallonia. The main symbol is the "bold rooster" (French: coq hardi), also named "Walloon rooster" (French: coq wallon, Walloon: cok walon), which is widely used, particularly on arms and flags. The rooster was chosen as an emblem by the Walloon Assembly on 20 April 1913, and designed by Pierre Paulus on 3 July 1913.[37] The Flag of Wallonia features the red rooster on a yellow background.

An anthem, Le Chant des Wallons (The Walloons' Song), written by Theophile Bovy in 1900 and composed by Louis Hillier in 1901, was also adopted. On September 21, 1913, the "national" feast day of Wallonia took place for the first time in Verviers, commemorating the participation of Walloons during the Belgian Revolution of 1830. It is held annually on the third Sunday of September. The Assembly also chose a motto for Wallonia, "Walloon Forever" (Walloon: Walon todi), and a cry, "Liberty" (French: Liberté). In 1998, the Walloon Parliament made all these symbols official except the motto and the cry.

Religion

The population of Wallonia is predominantly of Christian heritage. In 2016, 68% of residents of Wallonia declared themselves to be Roman Catholic (21% were practising Catholics and 47% were non-practising), 3% were Muslim, 3% were Protestant Christian, 1% were of other religions and 25% were non-religious.[38]

Languages

Official languages

French is by far the main language of Wallonia and holds official status; in the East Cantons, German is also official.[39] The German-speaking Community of Belgium accounts for about 2% of the region's population. Belgian French, which is also spoken in the Brussels-Capital Region, is similar to that spoken in France, with slight differences in pronunciation and some vocabulary differences, notably the use of the words septante (70) and nonante (90), as opposed to soixante-dix and quatre-vingt-dix in France.

There are noticeable Walloon accents, with the accent from Liège and its surroundings being perhaps the most striking. Other regions of Wallonia also have characteristic accents, often linked to the regional language.

Regional languages

Walloons traditionally also speak regional Romance languages, all from the Langues d'oïl group. Wallonia includes almost all of the area where Walloon is spoken, a Picard zone corresponding to the major part of the Hainaut Province, the Gaume (district of Virton) with the Lorrain language and a Champenois zone. There are also regional Germanic languages, such as the Luxembourgish language in Arelerland (Land of Arlon). The regional languages of Wallonia are more important than in France, and they have been officially recognized by the government. With the development of education in French, however, these dialects have been in continual decline. There is currently an effort to revive Walloon dialects; some schools offer language courses in Walloon, and Walloon is also spoken in some radio programmes, but this effort remains very limited.

Culture

Literature

In Walloon

Literature is written principally in French but also in Walloon and other regional languages, colloquially called Walloon literature. Walloon literature (regional language not French) has been printed since the 16th century. But it did have its golden age, paradoxically, during the peak of the Flemish immigration to Wallonia in the 19th century: "That period saw an efflorescence of Walloon literature, plays and poems primarily, and the founding of many theaters and periodicals."[40] The New York Public Library possesses a surprisingly large collection of literary works in Walloon, quite possibly the largest outside Belgium, and its holding are representative of the output. Out of nearly a thousand, twenty-six were published before 1880. Thereafter the numbers rise gradually year by year, reaching a peak of sixty-nine in 1903, and then they fall again, down to eleven in 1913. See 'Switching Languages', p. 153. Yves Quairiaux counted 4800 plays for 1860–1914, published or not. In this period plays were almost the only popular show in Wallonia. But this theater remains popular in the present-day Wallonia: Theater is still flourishing, with over 200 non-professional companies playing in the cities and villages of Wallonia for an audience of over 200,000 each year.[41] There are links between French literature and (the very small) Walloon literature. For instance Raymond Queneau set Editions Gallimard the publication of a Walloon Poets' anthology. Ubu roi was translated in Walloon by André Blavier ( an important pataphysician of Verviers, friend of Queneau), for the new and important Puppets theater of Liège of Jacques Ancion, the Al Botroûle theater "at the umbilical cord" in Walloon indicating a desire to return to the source (according to Joan Cross). But Jacques Ancion wanted to develop a regular adult audience. From the 19th century, he included the Walloon play Tati l'Pèriquî by E.Remouchamps and the avant-garde Ubu roi by A.Jarry.[42] For Jean-Marie Klinkenberg, "the dialectal culture is no more a sign of attachment to the past but a way to participate to a new synthesis".[43]

In French

Jean-Marie Klinkenberg (member of the Groupe µ) wrote that Wallonia, and literature in Wallonia, has been present in French language since its formation.[44] In their 'Histoire illustrée des lettres française de Belgique', Charlier and Hanse (editors), La Renaissance du livre, Bruxelles, 1958, published 247 pages (on 655 ), about the "French" literature in the Walloon provinces (or Walloon principalities of the Middle-Age, sometimes also Flemish provinces and principalities), for a period from the 11th to the 18th century. Among the works or the authors, the Sequence of Saint Eulalia (9th century), La Vie de Saint Léger (10th century), Jean Froissart (14th century in the County of Hainaut), Jean d'Outremeuse, Jean Lebel, Jean Lemaire de Belges (16th century from Bavay), the Prince of Ligne (18th century, Beloeil). There is a Walloon Surrealism,[45] especially in Hainaut Province. Charles Plisnier (1896–1952), born in Mons, won the Prix Goncourt in 1936, for his novel Mariages and for Faux Passeports (short stories denouncing Stalinism, in the same spirit as Arthur Koestler). He was the first foreigner to receive this honour. The Walloon Georges Simenon is likely the most widely read French-speaking writer in the world, according to the Tribune de Genève.[46][47] More than 500 million of his books have been sold, and they have been translated into 55 languages. There is a link between the Jean Louvet's work and the social issues in Wallonia.[48]

In Picard

Picard is spoken in Hainaut Province of western Belgium. Notable Belgian authors who wrote in Picard include Géo Libbrecht, Paul Mahieu, Paul André, Francis Couvreur and Florian Duc.

Mosan art, painting, architecture

Mosan art is a regional style of Romanesque art from the Meuse river valley in present-day Wallonia, and the Rhineland, with manuscript illumination, metalwork, and enamel work from the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries. Among them is the masterpiece of Renier de Huy and perhaps of the whole Mosan art Baptismal font at St Bartholomew's Church, Liège. The architecture of Roman churches of the Walloon country are also named mosan, exemplified by the Collegiate Church of Saint Gertrude in Nivelles, and the churches of Waha and Hastière, Dinant. The Ornamental brassware is also a part of the Mosan art and among these dinandiers Hugo d'Oignies and Nicholas of Verdun.

Jacques du Broeucq was a sculptor of the 16th century.

Flemish art was not confined to the boundaries of modern Flanders and several leading artists came from or worked in areas in which langues d'oïl were spoken, from the region of modern Wallonia, e.g. Robert Campin, Rogier van der Weyden (Rogier de la Pasture) and Jacques Daret. Joachim Patinir Henri Blès are generally called mosan painters. Lambert Lombard (Liège, 1505 – 1566) was a Renaissance painter, architect and theorist for the Prince-Bishopric of Liège. Gérard de Lairesse, Bertholet Flemalle were also important painters in the Prince-Bishopric of Liège.

Gustave Serrurier-Bovy (Liège, 1858 – Antwerp, 1910)[49] architect and furniture designer, credited (along with Paul Hankar, Victor Horta and Henry van de Velde) with creating the Art Nouveau style, coined as a style in Paris by Bing.[50] And in Liège also, principally Jean Del Cour, the sculptor of the Virgin in Vinâve d'Isle, Léon Mignon the sculptor of Li Tore and Louis Jéhotte of the statue of Charlemagne.

George Grard (1901—1984) was a Walloon sculptor, known above all for his representations of the female, in the manner of Pierre Renoir and Aristide Maillol, modelled in clay or plaster, and cast in bronze.

During the 19th and 20th centuries many original romantic, expressionist and surrealist Wallon painters emerged, including Félicien Rops, Paul Delvaux, Pierre Paulus, Fernand Verhaegen, Antoine Wiertz, René Magritte ... The avant-garde CoBrA movement appeared in the 1950s.

Music

There was an important musical life in Prince-Bishopric of Liège since the beginning. Between 1370 and 1468 flourished a school of music in Liège, with Johannes Brassart, Johannes de Sarto and firstly Johannes Ciconia, the third Master of Ars Nova.[51]

The vocal music of the so-called Franco-Flemish School developed in the southern part of the Low Countries and was an important contribution to Renaissance culture. Robert Wangermée and Philippe Mercier wrote in their encyclopedic book about the Walloon music that Liège, Cambrai and Hainaut Province played a leading part in the so-called Franco-Flemish School.[52]

Among them were Orlande de Lassus, Gilles Binchois, Guillaume Dufay In the 19th and 20th centuries, there was an emergence of major violinists, such as Henri Vieuxtemps, Eugène Ysaÿe (author of the unique opera in Walloon during the 20th century Piére li houyeû – Pierre the miner – based on a real incident which occurred in 1877 during a miners' strike in the Liège region), and Arthur Grumiaux, while Adolphe Sax (born in Dinant) invented the saxophone in 1846. The composer César Franck was born in Liège in 1822, Guillaume Lekeu in Verviers. More recently, André Souris (1899–1970) was associated with Surrealism. Zap Mama is a more international group.[53]

Henri Pousseur is generally regarded as a member of the Darmstadt School in the 1950s. Pousseur's music employs serialism, mobile forms, and aleatory, often mediating between or among seemingly irreconcilable styles, such as those of Schubert and Webern (Votre Faust), or Pousseur's own serial style and the protest song "We shall overcome" (Couleurs croisées). He was strongly linked to the social strikes in Liège during the 1960s.[54] He worked also with the French writer Michel Butor.

Cinema

Walloon films are often characterized by social realism. It is perhaps the reason why the documentary Misère au Borinage, and especially its co-director Henri Storck, is considered by Robert Stallaerts as the father of the Walloon cinema. He wrote: "Although a Fleming, he can be called the father of the Walloon cinema.".[55] For F. André between Misère au Borinage and the films like those of the Dardenne brothers (since 1979), there is Déjà s'envole la fleur maigre (1960) (also shot in the Borinage),[56] a film regarded as a point of reference in the history of the cinema.[57] Like those of the Dardenne brothers, Thierry Michel, Jean-Jacques Andrien, Benoît Mariage, or, e.g. the social documentaries of Patric Jean, the director of Les enfants du Borinage writing his film as a letter to Henri Storck. On the other hand, films such as Thierry Zéno's Vase de noces (1974), Mireille in the life of the others by Jean-Marie Buchet (1979), C'est arrivé près de chez vous (English title: Man bites dog) by Rémy Belvaux and André Bonzel (1992) and the works of Noël Godin and Jean-Jacques Rousseau are influenced by surrealism, absurdism and black comedy. The films of the Dardenne brothers are also inspired by the Bible and Le Fils for instance is regarded as one of the most spiritually significant films.[58]

Festivals

The Ducasse de Mons (Walloon French for Kermesse), is one of the UNESCO Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. It comprises two important parts: the procession, the descent and the ascent of the shrine of Waltrude, and the combat between Saint George and the dragon. The combat (after the procession), plays out on the Trinity Sunday between 12:30 pm and 1:00 pm on the Mons's central square. It represents the fight between Saint George (the good) and the dragon (the evil). The dragon is a mannequin carried and moved by the white men (fr:Hommes blancs). The dragon fights Saint George by attacking with his tail. Saint George on his horse turns clockwise and the dragon turns in the other direction. Saint George finally kills the dragon.

The Gilles of Binche and the giants' procession in Ath are also UNESCO Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Cuisine

Wallonia is famous for a number of different foods and drinks, a great many of which are specialties of certain cities or regions. The Liège waffle a rich, dense, sweet, and chewy waffle native to Liège, is the most popular type of waffle in Belgium, and can be found in stores and even vending machines throughout the country. Cougnou, or the bread of Jesus, is a sweet bread typically eaten around Christmas time and found throughout the region.

Other specialties include Herve cheese, an apple butter called sirop de Liège, the Garden strawberry of Wépion. Also notable is the Dinant specialty Flamiche: These cheese tarts are not found in window displays as they are meant to be eaten straight from the oven. As one restaurateur stated in a book about Walloon gastronomy "it is the client who waits for the flamiche, as the flamiche does not wait for the client".[59] There are also the Ardennes ham,[60] the tarte al djote from Nivelles, a dessert pie made with beet leaves and cheese,[61] while tarte au riz is a rice-pudding filled pie from Verviers. The Walloons of the Door Peninsula in Wisconsin have a tradition of making what is called a Belgian Pie but which is a flat pie more like a pizza covered with prune purée and topped with a thin cheese layer. These were made by the dozens in outdoor stone ovens for the many kermisses, in a tradition that dates back to immigration in the 1850s.

A signature Walloon sausage is called Belgian Trippe among the Walloon community of Northeastern Wisconsin on the Door Peninsula. It is a blend of pork and cabbage made differently from household to household and probably based on a traditional Walloon sausage such as Boudin Verte d'Orp. Cussette is a fresh cheese which gets it's airborne P. roqueforti culture from a tradition of making it in the kitchen. This is aged only one week at 30 degrees C, until it develops a faint blue cast and a tang. Walloon headcheese differs from the German in that it is more finely ground, includes bits of cartilage, and is allowed to sit for a month or two in a cool place before being eaten.

In terms of drink, Wallonia mirrors Belgium as a whole; beer and wine are both popular, and a great diversity of beers are made and enjoyed in Wallonia. Installed in Bierghes in the Senne valley, the Gueuzerie Tilquin is the only gueuze blendery in Wallonia. Wallonia boasts three of the seven Trappist beers (from Chimay, Orval and Rochefort) in addition to a great number of other locally brewed beers. Wallonia is also home to the last bastion of traditional rustic saison, most notably those produced at the Brasserie de Silly and the Brasserie Dupont (located in Tourpes, in the region of Western Hainaut Province historically known for its production of rustic farmhouse ales). Jupiler, the best-selling beer in Belgium, is brewed in Jupille-sur-Meuse in Liège. Wallonia also home to a Jenever called Peket, and a May wine called Maitrank.

Transportation

Airports

The two largest cities in Wallonia each have an airport. The Brussels South Charleroi Airport has become an important passenger airport, especially with low fares companies such as Ryanair or Wizzair. It serves as a low-cost alternative to Brussels Airport, and it saw 7 303 720 passengers in 2016. The Liège Airport is specialized in freight, although it also operates tourist-oriented charter flights. Today, Liège is the 8th airport for European freight and aims to reach the 5th rank in the next decade.

Railways, motorways, buses

TEC is the single public transit authority for all of Wallonia, operating buses and trams. Charleroi is the sole Walloon city to have a metro system, the Charleroi Pre-metro.

Wallonia has an extensive and well-developed rail network, served by the Belgian National Railway Company, SNCB.

Wallonia's numerous motorways fall within the scope of the TransEuropean Transport network programme (TEN-T). This priority programme run by the European Union provides more than 70,000 km of transport infrastructure, including motorways, express rail lines and roadways, and has been developed to carry substantial volumes of traffic.[62]

Waterways

With traffic of over 20 million tonnes and 26 kilometres of quays, the autonomous port of Liège (PAL) is the third largest inland port in Europe.[63] It carries out the management of 31 ports along the Meuse and the Albert Canal. It is accessible to sea and river transporters weighing up to 2,500 tonnes, and to push two-barge convoys (4,500 tonnes, soon to be raised to 9,000 tonnes). Even if Wallonia does not have direct access to the sea, it is very well connected to the major ports thanks to an extensive network of navigable waterways that pervades Belgium, and it has effective river connections to Antwerp, Rotterdam and Dunkirk.[64]

On the west side of Wallonia, in Hainaut Province, the Strépy-Thieu boat lift, permits river traffic of up to the new 1350-tonne standard to pass between the waterways of the Meuse and Scheldt rivers. Completed in 2002 at an estimated cost of €160 million (then 6.4 billion Belgian francs) the lift has increased river traffic from 256 kT in 2001 to 2,295 kT in 2006.

Brussels South Charleroi Airport

Brussels South Charleroi Airport Namur Railway Station

Namur Railway Station.jpg.webp) Charleroi Pre-metro

Charleroi Pre-metro.JPG.webp) TEC Bus in Liège

TEC Bus in Liège

International relations

Trade

The Walloon Export and Foreign Investment Agency (AWEX) is the Wallonia Region of Belgium's government agency in charge of foreign trade promotion and foreign investment attraction.[65]

The AWEX organizes regular trade missions to the promising market of Kazakhstan, where it has a representative office in Almaty. In 2017, the AWEX together with the Flanders Investment and Trade brought a delegation of 30 companies to Astana and Almaty, the two largest cities in Kazakhstan.[66]

See also

- History of coal mining

- Manifesto for Walloon culture

- Huguenots

References

- "be.STAT". Bestat.statbel.fgov.be.

- "Structuur van de bevolking | Statbel". Statbel.fgov.be.

- "Vlaamse overheid – Taalwetwijzer – Wetgeving". Vlaanderen.be.

- Walloon: Waloneye; German: Wallonien [vaˈloːni̯ən] (

listen) or Wallonie [valoˈniː]; Dutch: Wallonië [ʋɑˈloːnijə] (

listen) or Wallonie [valoˈniː]; Dutch: Wallonië [ʋɑˈloːnijə] ( listen)

listen) - The Belgian Constitution (PDF). Brussels, Belgium: Belgian House of Representatives. May 2014. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

Article 3: Belgium comprises three Regions: the Flemish Region, the Walloon Region and the Brussels Region. Article 4: Belgium comprises four linguistic regions: the Dutch-speaking region, the French-speaking region, the bilingual region of Brussels-Capital and the German-speaking region.

- "BBC – Languages – Languages". Bbc.co.uk.

- "Gouvernement de Wallonie". Wallonie.be. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- For example, the CIA World Factbook states Wallonia is the short form and Walloon Region is the long form. The Invest in Wallonia website Archived 2009-09-08 at the Wayback Machine and the Belgian federal government Archived 2009-02-21 at the Wayback Machine use the term Wallonia when referring to the Walloon Region.

- "Walloon". Etymonline.com.

- "Welsh | Etymology, origin and meaning of the name Welsh by etymonline". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- (French) Albert Henry, Histoire des mots Wallons et Wallonie, Institut Jules Destrée, Coll. «Notre histoire», Mont-sur-Marchienne, 1990, 3rd ed. (1st ed. 1965), foodnote 13 p. 86.

- Dawson, P. L. Kessler and Edward. "Kingdoms of the Barbarians - Celtic Tribes". Historyfiles.co.uk. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Footnote: In medieval French, the word Liégeois referred to all the inhabitants of the Principality vis-à-vis the other inhabitants of the Low-countries, the word Walloons being only used for the French-speaking inhabitants vis-à-vis the other inhabitants of the Principality. Stengers, Jean (1991). "Depuis quand les Liégeois sont-ils des Wallons?". In Hasquin, Hervé (ed.). Hommages à la Wallonie [mélanges offerts à Maurice Arnould et Pierre Ruelle] (in French). Brussels: éditions de l'ULB. pp. 431–447.

- (in French) Maurice Delbouille Romanité d'oïl Les origines : la langue – les plus anciens textes in La Wallonie, le pays et les hommes Tome I (Lettres, arts, culture), La Renaissance du Livre, Bruxelles,1977, pp.99–107.

- "A young region with a long history (from 57BC to 1831)". Gateway to the Walloon Region. Walloon Region. 2007-01-22. Archived from the original on 2008-05-01. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- Kramer, pg. 59, citing M. Gysseling (1962). "La genèse de la frontière linguistique dans le Nord de la Gaule". Revue du Nord (in French). 44 (173): 5–38, in particular 17. doi:10.3406/rnord.1962.2410.

- "Wallonie : une région en Europe" (in French). Ministère de la Région wallonne. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- "The region asserts itself (from 1840 to 1970)". Gateway to the Walloon Region. 2007-01-22. Archived from the original on 2008-05-01. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- "Belgium: largest cities and towns and statistics of their population". Archived from the original on March 28, 2006.

- "HOUILLE : Définition de HOUILLE". cnrtl.fr.

- Allan H. Kittel, "The Revolutionary Period of the Industrial Revolution", Journal of Social History, Vol. I, n° 2 (Winter 1967), pp. 129–130.

- Philippe Destatte, L'identité wallonne, Institut Destrée, Charleroi, 1997, pages 49–50 ISBN 2-87035-000-7

- "Welcome". erih.net. Archived from the original on 2013-07-31.

- "Walloon incentives - Portal Wallonia". Archived from the original on 2011-05-21. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- "Wallonia battles wasteland image". BBC News. October 6, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- According to La Libre Belgique on 26 August 2010: 9.8 million visitors in 2009 (2.8 in Brussels), 6% of the regional economy (15% in Brussels)

- "AGC Flat Glass: Leadership through innovation". Uwe.be.

- "Carmeuse: expansion through partnership and knowledge". Uwe.be. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- "IBA's growth still accelerating". Uwe.be. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- "Sonaca: Increasing visibility in North America". Uwe.be. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- "Official Website of the Walloon Region". Archived from the original on 2008-06-11. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- There is also a mention of Wallonie in 1825 : (in French) « les Germains, au contraire, réservant pour eux seuls le noble nom de Franks, s'obstinaient, dès le onzième siècle, à ne plus voir de Franks dans la Gaule, qu'ils nommaient dédaigneusement Wallonie, terre des Wallons ou des Welsches » Augustin Thierry, Histoire de la conquête de l'Angleterre par les Normands, Éd. Firmin Didot, Paris, 1825, tome 1, p. 155. read online

- (in French) Albert Henry, Histoire des mots Wallons et Wallonie, Institut Jules Destrée, Coll. «Notre histoire», Mont-sur-Marchienne, 1990, 3rd ed. (1st ed. 1965), p. 12.

- (in French) «C'est cette année-là [1886] que naît le mot Wallonie, dans son sens politique d'affirmation culturelle régionale, lorsque le Liégeois Albert Mockel crée une revue littéraire sous ce nom» Philippe Destatte, L'identité wallonne p. 32.

- La préhistoire latine du mot Wallonie in Luc Courtois, Jean-Pierre Delville, Françoise Rosart & Guy Zélis (editors), Images et paysages mentaux des XIXe et XXe siècles de la Wallonie à l'Outre-Mer, Hommage au professeur Jean Pirotte à l'occasion de son éméritat, Academia Bruylant, Presses Universitaires de l'UCL, Louvain-la-Neuve, 2007, pp. 35–48 ISBN 978-2-87209-857-6, p. 47

- "AllStates Flag Co., Inc". Allstates-flag.com. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- lesoir.be (28 January 2016). "75% des francophones revendiquent une identité religieuse". lesoir.be. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- "La Constitution belge (Art. 4)" (in French). the Belgian Senate. May 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

La Belgique comprend quatre régions linguistiques : la région de langue française, la région de langue néerlandaise, la région bilingue de Bruxelles-Capitale et la région de langue allemande.

- 'Switching Languages', Translingual Writers Reflect on Their Craft, Edited by Steven G. Kellman Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003, p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8032-2747-7

- "The Walloon language page". skynet.be.

- Joan Gross, Speaking in Other Voices: An Ethnography of Walloon Puppet Theaters. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Press, 2001, ISBN 1-58811-054-0

- Benoît Denis et Jean-Marie Klinkenberg, Littérature : entre insularité et activisme in Le Tournant des années 1970. Liège en effervescence, Les Impressions nouvelles, Bruxelles, 2010, pp. 237–253, p. 252. French : Ancion monte l'Ubu rwèen 1975 (...) la culture dialectalisante cesse d'être une marque de passéisme pour participer à une nouvelle synthèse...

- Histoire de la Wallonie, Privat Toulouse, 2004, ISBN 2-7089-4779-6 p. 220. French: Le latin apporté en Gaule par les légions romaines avait fini par éclater en de multiples dialectes (...) peu à peu, pour répondre aux besoins des pouvoirs publics et religieux se forme une langue standard. Dans ce processus qui aboutira à l'élaboration du français, la Wallonie est présente dès les premières heures.

- An Paenhuysen Surrealism in the Provinces. Flemish and Walloon Identity in the Interwar period in Image&Narrative, n° 13, Leuven November, 2005

- "L'écrivain français le plus dans le monde". Tdg.ch. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- "Maigret and his master". theage.com.au. 2003-09-14.

- Cody, Gabrielle H.; Sprinchorn, Evert (2007). The Columbia Encyclopedia of Modern Drama. ISBN 9780231144223.

- "Gustave Serrurier-Bovy | artnet". Artnet.com.

- Your Antique Furniture Guide, Art Nouveau in Belgium, Efi-costarica.com

- French Le troisième grand Maître de l'Ars Nova in Robert Wangermée et Philippe Mercier, La musique en Wallonie et à Bruxelles, La Renaissance du livre, Bruxelles, 1980, Tome I, pp. 37–40.

- Robert Wangermée et Philippe Mercier, La musique en Wallonie et à Bruxelles, La Renaissance du livre, Bruxelles, 1980, Tome I, p. 10.

- Wangermée, Robert (1995). Dictionnaire de la chanson en Wallonie et à Bruxelles. ISBN 9782870096000.

- The "Trois Visages de Liege", (...) full of provocative sound collages [evokes..] not only moments in sonic civic history, but the sounds of its historical events as well: wildcat strikes and their ensuing violence in 1960, protests against new laws being enacted, etc. See Acousmatrix 4: Scambi/Trois Visages de Liege/Paraboles Mix

- Historical dictionary of Belgium (Scarecrow press, 1999, p. 191 ISBN 0-8108-3603-3).

- Cinéma wallon et réalité particulière, in TOUDI, n° 49/50, septembre-octobre 2002, p.13.

- "les films repères dans l'histoire du cinéma". autourdu1ermai.fr.

- "The Arts & Faith Top 100 Films". Artsandfaith.com.

- "Dinant". Archived from the original on 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- "Ardenne Ham". Practicallyedible.com. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- The Simon and Schuster international pocket food guide, 1981.

- "AWEX". Investinwallonia.be. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- "Liege port authority". Liege.port-autonome.be. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- "Qui sommes-nous? – logistics in Wallonia". Logisticsinwallonia.be.

- "AWEX (WALLONIA FOREIGN TRADE AND INVESTMENT AGENCY)". Skywin.be.

- "Economic cooperation between Kazakhstan and Belgium discussed in Brussels". Mfa.kz.

- "ベルギー3地域と「友好交流及び相互協力に関する覚書」を締結". Pref.aichi.jp. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- "Maryland Sister States Program". Maryland Secretary of State. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

Further reading

- Johannes Kramer (1984). Zweisprachigkeit in den Benelux-ländern (in German). Buske Verlag. ISBN 978-3-87118-597-7.

External links

![]() Media related to Wallonia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wallonia at Wikimedia Commons