Watkins Glen International

Watkins Glen International, nicknamed "The Glen", is an automobile race track located in the town of Dix just southwest of the village of Watkins Glen, New York, at the southern tip of Seneca Lake. It was long known around the world as the home of the Formula One United States Grand Prix, which it hosted for twenty consecutive years (1961–1980). In addition, the site has also been home to road racing of nearly every class, including the World Sportscar Championship, Trans-Am, Can-Am, NASCAR Cup Series, the International Motor Sports Association and the IndyCar Series. The facility is currently owned by NASCAR.

| "The Glen" | |

|---|---|

| |

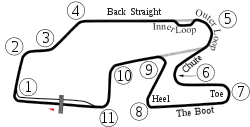

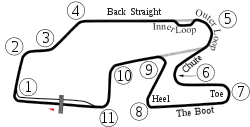

Long course at Watkins Glen International  Short course at Watkins Glen International | |

| Location | Watkins Glen, New York |

| Time zone | UTC−5 / −4 (DST) |

| Coordinates | 42°20′13″N 76°55′38″W |

| Capacity | 38,900[1] |

| FIA Grade | 2 |

| Owner | NASCAR |

| Operator | NASCAR |

| Opened | permanent circuit in 1956 |

| Former names | Watkins Glen Grand Prix Circuit (1956–1971) Watkins Glen International Raceway (1972–2000) |

| Major events | Current: IMSA SportsCar Championship 6 Hours of Watkins Glen (1956–1981, 1984–2019, 2021–present) NASCAR Cup Series Go Bowling at The Glen (1957, 1964–1965, 1986–2019, 2021–present) NASCAR Xfinity Series Sunoco Go Rewards 200 at The Glen (1991–2019, 2021–present) ARCA Menards Series General Tire Delivers 100 (1993–2004, 2008–2009, 2014–2019, 2021–present) GT World Challenge America (1992, 1996–1998, 2007–2010, 2018–2019, 2021–present)

Formula One United States Grand Prix (1961–1980) IndyCar Series Grand Prix at The Glen (1979–1981, 2005–2010, 2016–2017) NASCAR Camping World Truck Series United Rentals 176 (1996–2000, 2021) Stadium Super Trucks (2017) Crown Royal 200 at the Glen (1984–1991, 2001–2011, 2021) |

| Grand Prix Circuit (with Inner Loop Chicane) (1992–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt and concrete |

| Length | 3.450 miles (5.552 km) |

| Turns | 11 |

| Race lap record | 1:23.9166 ( |

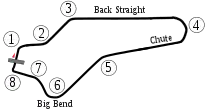

| Short Circuit (with Inner Loop Chicane) (1992–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.450 miles (3.943 km) |

| Turns | 8 |

| Race lap record | 59.920 ( |

| Short Circuit (with Esses Chicane) (1979–1991)[2] | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.428 miles (3.907 km) |

| Turns | 8 |

| Grand Prix Circuit (1971–1974, 1986–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 3.377 miles (5.435 km) |

| Turns | 11 |

| Race lap record | 1:35.600 ( |

| Grand Prix Circuit (with Esses Chicane) (1975–1985) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 3.377 miles (5.435 km) |

| Turns | 11 |

| Race lap record | 1:34.068 ( |

| Sports Car Circuit (1971) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.430 miles (3.911 km) |

| Turns | 7 |

| Race lap record | 1:06.083 ( |

| Original Grand Prix Circuit (1956–1970) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.350 miles (3.782 km) |

| Turns | 8 |

| Race lap record | 1:02.600 ( |

| Second Public Road Course (1953–1955) | |

| Surface | Asphalt, cobbles, concrete, wood, dirt, steel |

| Length | 4.600 miles (7.403 km) |

| Race lap record | 3:10.800 ( |

| Original Public Road Course (1948–1952) | |

| Surface | Asphalt, cobbles, concrete, wood, dirt, steel |

| Length | 6.600 miles (10.622 km) |

| Turns | 28 (approximately) |

| Race lap record | 5:13.500 ( |

| Website | www |

The course was opened in 1956 to host auto races previously held on public roads in and around the village. The circuit's current layout has more or less been the same since 1971, with minor modifications after the fatal crashes of François Cevert in 1973 and J.D. McDuffie in 1991.

The circuit is a Mecca of North American road racing and is a popular venue among fans and drivers.

The site has also hosted music concerts: the 1973 Summer Jam, featuring The Allman Brothers Band, the Grateful Dead and The Band and was attended by 600,000 fans;[3] and two Phish festivals: Super Ball IX in 2011 and Magnaball in 2015.

Layouts

The Watkins Glen International racecourse has undergone several changes over the years, with five general layouts widely recognized over its history. Currently, two distinct layouts are used: the "Boot" layout (long course) and the "NASCAR" layout (short course).

Public roads

The first races in Watkins Glen were organized by Cameron Argetsinger, whose family had a summer home in the area. With local Chamber of Commerce approval and SCCA sanction, the first Watkins Glen Grand Prix took place in 1948 on a 6.6-mile (10.6 km) course[4] over local public roads.[5] For the first few years, the races passed through the heart of the town with spectators lining the sidewalks. However, after a car driven by Fred Wacker left the road in the 1952 race, killing seven-year-old Frank Fazzari and injuring several others, the race was moved to a new location on a wooded hilltop southwest of town. The original 6.6-mile (10.6 km) course is listed in the New York State Register and National Register of Historic Places as the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Course, 1948–1952.[6]

The second layout 4.6-mile (7.4 km) began use in 1953 and also used existing roads. The Watkins Glen Grand Prix Corporation was formed to manage spectators, parking, and concessions. This arrangement lasted three years.

Grand Prix Course

The first permanent course, known as the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Race Course was constructed on 550 acres, overlapping part of the previous street course. It was designed by Bill Milliken and engineering professors from Cornell University. The layout measured 2.350-mile (3.782 km). This course was used from 1956 to 1970. In 1968 the sports car race was extended to six hours.

Short Course

The circuit underwent a major overhaul for the 1971 season. The "Big Bend" and the turns leading up to it were eliminated and replaced with a new pit straight. The pits and start/finish line were moved to this new straightaway. "The 90" now became Turn 1 instead of Turn 8.

When the 1971 Six Hours of Watkins Glen arrived in July 1971, the overall circuit renovations were still unfinished. The short course had been finished, but the Boot segments were not complete, nor was the new pit area. The 1971 Six Hours race was run on the short course layout. That layout colloquially became known as the 1971 Six Hours Course. In addition, for 1971 only, the cars used the original start/finish line and the old pits.

When NASCAR returned to the track in 1986, it used the short course layout. IMSA initially used the "Boot", but eventually, that series also began using the shorter 1971 layout.

The short course was slightly lengthened in 1992 (see "Inner Loop" below).

Long Course (The "Boot")

The most significant change to the track, a new segment known as "The Boot", was finished in time for the Formula One race in 1971. The start-finish line was moved to the new pit straight as planned. At the end of the backstretch, after the Loop-Chute, cars swept left into a new four-turn complex that departed from the old layout, curling left-hand downhill through the woods. The track followed the edge of the hillside to two uphill right-hand turns, over an exciting blind crest into a right-hand turn, down and up into a left-hand turn rejoining the old track.

The new layout measured 3.377 mi (5.435 km). With its intrinsic link to the Formula One race, it became known colloquially as the Grand Prix Circuit.

For 1972, the Six Hours sportscar race also began using the full "Boot" layout. By that time, nearly all facility improvements were completed. The pits and start/finish line were permanently moved to the new pit straight.

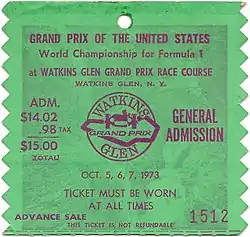

In 1973, French driver François Cevert, a previous winner at the Glen, died in a crash during practice at the 1973 United States Grand Prix. This led course officials in 1975 to add a fast right-left chicane to slow speeds in the turn 3-4 Esses section. Dubbed the "Scheckter Chicane", it was eliminated in 1985.

In the early 1990s, the IMSA sports cars bypassed the "Boot" in favor of the short course. NASCAR events have never used the Boot layout. The "Long/Boot" course was slightly lengthened in 1992 (see "Inner Loop" below). In the mid-2000s, the Boot segment, which had seen little use in many years, was repaved and upgraded. When the IndyCar Series returned to Watkins Glen starting in 2005, they used the Boot segment.

The entire course was repaved in 2015. There has been a renewed interest and appreciation of the full Grand Prix Course layout in recent years. Consideration had even been made for NASCAR to start using the Boot.[7]

Inner Loop

The most recent significant change to the course was made in 1992, after several serious crashes at the "Loop" at the end of the backstretch. During the 1989 Budweiser at the Glen, Geoff Bodine blew a tire at the end of the backstretch. He broke into a hard spin and sailed straight off the track, crashing head-on into the barrier. In 1991, during the IMSA Camel Continental VIII, Tommy Kendall's Intrepid RM-1 prototype crashed in the Loop, severely injuring his legs. Seven weeks later, NASCAR Winston Cup driver J. D. McDuffie died in an accident at the same site during the 1991 Budweiser at The Glen.

Before the 1992 season, track officials constructed a bus stop chicane along the back straight just before the Loop. Dubbed the "Inner Loop", it led into what was now being called the "Outer Loop." This addition slightly increased the lap distance for both layouts.

History

Watkins Glen Grand Prix

Along with the annual SCCA race, the track hosted its first professional race (NASCAR Grand National Division) in 1957. It hosted its first international event with the Formula Libre races from 1958 to 1960. Among the drivers participating were Jack Brabham, Stirling Moss, Phil Hill, and Dan Gurney.

United States Grand Prix

After two editions of the Formula One United States Grand Prix that were deemed less than successful (Sebring in 1959, and Riverside in 1960), promoters were looking for a new venue to become the permanent home for the United States Grand Prix.

In 1961, just six weeks before the scheduled date for another Formula Libre race that fall, Argetsinger was tapped to prepare Watkins Glen for the final round of the Formula One World Championship. While many of the necessary preparations had already been made, new pits were constructed to satisfy international standards of pit boxes with overhead cover.

Seven American drivers participated, and the 1961 United States Grand Prix was won by British driver Innes Ireland in a Lotus-Climax. American Dan Gurney driving a Porsche 718 placed second. Having already won both Driver's and Constructor's World Championships and still mourning the death of Wolfgang von Trips at the 1961 Italian Grand Prix, Ferrari decided not to compete in the United States GP. Ferrari's decision not to travel to the United States for the season's final round deprived Hill of participating in his home race as the newly crowned World Champion, and Hill appeared only as the event's Grand Marshal.

The United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen quickly became an autumnal tradition as huge crowds of knowledgeable racing fans flocked to Upstate New York each year amid the region's spectacular autumn leaf color. The race was also among the most popular on the global Grand Prix calendar with the teams and drivers because its starting and prize money often exceeded those of the other races combined. The race received the Grand Prix Drivers' Association award for the best organized and best staged GP of the season in 1965, 1970, and 1972.

One fixture of the USGP at Watkins Glen was the starter for the races, Richard Norman "Tex" Hopkins. Hopkins was the most recognizable starter in Grand Prix racing, wearing a lavender suit, clenching a big cigar in his mouth, and giving the job everything he had. Once the cars had taken their places, Hopkins strode across the front of the grid with his back to the field, turned, and jumped into the air while waving the national flag to start the race. He would similarly meet the winner at the finish, this time waving the checkered flag as the car crossed the line.

Before the 1971 race, the course underwent its most significant changes of the Grand Prix era, as it was extended from 2.35 mi (3.78 km) to 3.377 mi (5.435 km) by the addition of four corners in a new section called the 'Boot' or 'Anvil'. The new layout departed from the old course near the south end into a curling downhill left-hand turn through the woods. The track followed the edge of the hillside to two consecutive right-hand turns, over an exciting blind crest to a left-hand turn, and back onto the old track. In addition, the circuit was widened and resurfaced. The pits and start-finish line were moved back before the northwest right-angle corner known as "The 90". In 1975, a fast right-left chicane was added to slow speeds through the series of corners in the Esses section.

Despite the improvements, the circuit was unsafe for the increasingly faster and stiffer ground effect cars of the late 1970s. A few horrendous, sometimes fatal accidents occurred (such as those that claimed the lives of Helmut Koinigg and François Cevert). Increasingly rowdy segments of the crowd began to tarnish its image as well. Finally, in May 1981, several months after Alan Jones had won the 1980 race for Williams, the International Auto Sports Federation removed the race from its schedule because the track had failed to pay its $800,000 debt to the teams.[8]

American road-racing Mecca

The Glen hosted a variety of other events throughout the Grand Prix years: from Can-Am, Trans-Am, IROC, and Endurance Sports car racing, to Formula 5000 and the CART series, these races strengthened the circuit's reputation as the premier road racing facility in the United States. From 1968 through 1981, the "Six Hours at The Glen" endurance race featured top drivers such as Mario Andretti, Jacky Ickx, Pedro Rodríguez, and Derek Bell. Different races were sometimes featured together on the same weekend (e.g., Six Hours and Can-Am) and drew sizable crowds. However, without a Formula One race, the circuit struggled to survive. It finally declared bankruptcy and closed in 1981.

Renovation

The track was not well maintained for two years and hosted only a few SCCA meets without spectators. In 1983, Corning Enterprises, a subsidiary of nearby Corning, partnered with International Speedway Corporation to purchase the track and rename it Watkins Glen International.

The renovated track, with the chicane at the bottom of the Esses removed, reopened in 1984 with the return of IMSA with the Camel Continental I,[9] which would be conducted until 1995, with the last two years under the name "The Glen Continental" after Camel's withdrawal from IMSA. (The event was numbered with Roman numerals.)

In 1986, the top NASCAR series returned to Watkins Glen after a long layoff, holding one of only three road races on its schedule (two beginning in 1988), using the 1971 Six Hours course, raced when the new section off the Loop-Chute was not finished in time. As the cars come off the Loop-Chute, instead of making the downhill left into Turn 6, the cars shot straight through the straight and headed toward Turn 10, as was the case from 1961 until 1970.

NASCAR Busch Series (now called Xfinity Series) action would arrive in 1991 with a 150-mile (240 km) race on the weekend of the Camel Continental, won by Terry Labonte, who would be a master of the circuit during its Busch Series races, winning the inaugural race, and winning three consecutive races from 1995 until 1997. The 1995 race would be the first conducted as a 200-mile (320 km) race, and became the first Busch Series race to be televised on broadcast network television, as CBS broadcast the race live until TNN took over in 1997.

Only twice—1998 and 1999—did a Busch Series regular driver win the race. The first seven races were won by Winston Cup Series regular drivers, sometimes referred to as "Buschwhackers", during their off-week. In 1998, the race went against the Cup race in Sonoma, California, eliminating the idea, and stayed that way until 2000. In 2001, the race was run the day after the first Saturday in July.

However, the race was eliminated from the schedule after the 2001 season, only to return in 2005 as an undercard to the Nextel Cup race.

A pair of incidents in 1991 resulted in a massive overhaul of the circuit's safety. During the IMSA Camel Continental VIII, Tommy Kendall's prototype crashed in Turn 5, severely injuring his legs. Seven weeks later, NASCAR Cup Series driver J. D. McDuffie died in an accident at the same site in the 1991 Budweiser at the Glen. Track officials added a bus stop chicane to the back straight in Spring 1992.

In 1996, the Glen Continental reverted to a six-hour format, again called the Six Hours at the Glen with the IMSA format, and stayed there until a split in American sports car racing. In 1998, the race became an event sanctioned by the Sports Car Club of America under their United States Road Racing Championship. In 1999, the FIA GT series staged a 500 km race of three hours with some USRRC entrants after USRRC canceled the last two rounds of their season before their six-hour event at the track. The following year, the six-hour race returned once again with the newly founded Grand American Road Racing Association (Grand-Am) sanctioning the event. The event is now sanctioned by IMSA with the WeatherTech SportsCar Championship. The six-hour race is now the third part of the four-part North American Endurance Cup series.

In 1997, International Speedway Corporation became the sole owner of the course, as Corning Enterprises believed they had completed their intended goals to rebuild the race track and increase tourism in the southern Finger Lakes region of New York State.

The circuit annually hosts one of the nation's premier vintage events, the Zippo U.S. Vintage Grand Prix. When the fiftieth anniversary of road racing in Watkins Glen was celebrated during the 1998 racing season, this event was the climax, returning many original cars and drivers to the original 6.6-mile (10.6 km) street circuit through the village during the Grand Prix Festival Race Reenactment.

After a 25-year layoff, major-league open-wheel racing returned to the track as one of three road courses on the 2005 Indy Racing League schedule. In preparation, the circuit was overhauled again. Grandstands from Pennsylvania's Nazareth Speedway, which had closed, were installed, the gravel in The 90 was removed and replaced with a paved runoff area, and curbing was cut down for the Indy Racing League event. Previously, the high curbing in the chicane had become a place where Cup Series cars would bounce high off the curbing, creating an ideal opportunity for cars to lose control and to slow cars. Other areas of the track received improvements: the exits of turn 2 (the bottom of the esses), the chicane, turn 6 (the entrance to the boot), turn 9, and turn 11 all had additional runoff areas created and safety barrier upgrades. The carousel runoff was paved, and turn 1 (the 90), and the esses were paved in the winter of 2006–07. Augmenting what was already in place along the front stretch, additional high safety fences were installed on the overpasses crossing the service roads at the top of the esses and just out of the boot immediately after the exit of turn 9.

Another overhaul for 2006 made fundamental changes to the circuit for the first time since 1992. Officials installed a new control tower, which includes booths for the officials, timing and scoring, television and radio (the new position allows broadcasters to see more action from Turn 10 through the foot of the Esses), and the public address announcer on top of the new front stretch grandstand, moving the start-finish line farther ahead of the bridge, as the start-finish line is moved 380 feet (120 m) farther toward The 90 in order to accommodate the new timing and scoring post. The new start-finish line also meant the starting lights used for club races were moved farther ahead, creating more action off Turn 11 as tactics changed with the later finish line, where slingshot moves could become paramount to the finish. A new media center was constructed to replace the former building, which also had been the control tower with the 1971 improvements. The aging structure had been the bane of many professional media members during those years with many uncomplimentary things published and broadcast about its inadequacies, especially the lack of insulation, air conditioning, few (if any) amenities that other facilities had, which resulted in race control moving to the new control tower at the start-finish line in 2006. Plans were made to move the new media center back to allow an entire 43-car NASCAR grid. Other changes to the infrastructure included the purchase of adjoining property. Most of Bronson Hill Road was incorporated as a service road to the facility. A new section of Bronson Hill leading up from NY 414 was built as the main ingress road to the facility, bending south at Gate 6 and continuing to County Road 16, just south of the credentials and sheriff's office buildings.

Track safety also is constantly changing, and constant training is needed. Race Services Inc. provides the track with volunteers to work Fire-Rescue, Medical, Grid personnel, and Corner workers to help keep drivers and spectators safe.

The Argetsinger family is an advisor to the circuit. The track named the trophy for the inaugural Watkins Glen Indy Grand Prix presented by Argent in honor of the late patriarch, Cameron.

On Tuesday, March 6, 2007, just before 9 pm, a fire destroyed the recently remodeled Glen Club situated on top of the esses. Originally called the Onyx Club (named for the sponsor, Onyx Cologne), the Glen Club was used primarily as an upscale venue for race fans. After being recently remodeled, it was advertised as a social venue for locals for weddings, business meetings, etc. No cause could be determined, and the building was a total loss. The loss included irreplaceable, unique original motorsport artwork donated to the facility by several artists and other racing memorabilia. Glen officials were quoted in local media stories as being adamant that the loss of the Glen Club would not affect the 2007 racing schedule.

For 2007, Watkins Glen International again improved the facility, specifically the track surface. All of turns 1 (the "90"), 5 (the "Loop-Chute") and 6 (entry turn into the "Boot") were repaved. A temporary "Glen Club" replaced the permanent structure destroyed by fire at the races in 2007, which was replaced with another permanent building. New sponsors for both the INDY and NASCAR weekends were signed to multi-year deals. Camping World became the sponsor of the "Camping World Grand Prix" INDY weekend at the Glen through 2010. The NASCAR weekend at the Glen received a double shot—Zippo Manufacturing announced a three-year extension of the Busch-Nationwide Series race, the "Zippo 200". The NASCAR Cup Series race became known as "The Heluva Good! Sour Cream dips at the Glen". Additionally, Brad Penn lubricants of Pennsylvania (former Kendall Oil refinery) was announced as the sponsor of the annual vintage sports car weekend for 2007 and 2008. IndyCar took a six-year hiatus from the facility when the series pulled out of the Glen after 2010 due to a dispute with track owner ISC.

In June 2011, Tony Stewart and Lewis Hamilton participated in the "Mobil 1 Seat Swap". Stewart drove his No. 14 Mobil 1 Chevy for four laps around the circuit while Hamilton drove the MP4-23, Vodafone McLaren Mercedes's entry in the 2008 Formula One season. After some time, both drivers swapped cars and drove more laps around the circuit. The event was open to the public, and it was hoped that it would renew interest in the track. Before this event, the curbs on some of the turns were changed, the white rumble strips being replaced by the more common, red-white designs seen on most road courses around the world.

In July 2011, WGI hosted a Phish concert. This is the first concert that WGI has held since the Summer Jam.

In October 2012, the track suffered damage from Hurricane Sandy, with damage reported to be up to $50,000.[10]

Prior to the 2014 season, the track cleaned out a storage barn on track property when the original Dunlop Bridge was found. The bridge was initially used as a VIP area for Dunlop until being moved for use as the starters stand years later. It was taken down and replaced by a new starters stand during renovations in 2006. The bridge was put back up at the exit to the 90 near the original location where it once stood near the original start/finish line for the track and is now once again used for VIP use by companies on race weekends, with the company sponsoring the bridge.

After the 2014 racing season, it was announced that the 2015 racing season would conclude with the NASCAR weekend in early August. This was to allow for a complete repaving of the track. The repave involved removing the entire racing surface. In some places, the track was taken down to the dirt roadbed. This was funded not only by International Speedway Corporation but with a grant from New York State.

In March 2015, due to their previous concert's success, Phish said they would do another concert at WGI in late August.

In August 2015, with repaving already having taken place in the Boot, NASCAR announced that they are considering running the complete Grand Prix Course.[11] But as of 2022, NASCAR is still not using the Boot, and the use or not of the Boot is still a debate between NASCAR and fans.[12]

2016 would see the return of IndyCar racing to Watkins Glen, with the track being added to the schedule following the collapse of plans for a street race in Boston. It was held over the Labor Day weekend and used the full layout: ICS officials were also negotiating with WGI to race there permanently.[13]

No races were held in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lap Records

The official race lap records at Watkins Glen International are listed as:

| Category | Time | Driver | Vehicle | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Prix Circuit (with Inner Loop Chicane): 5.552 km (1992–present)[2] | ||||

| IndyCar | 1:23.9166 | Sébastien Bourdais | Dallara DW12 | 2017 IndyCar Grand Prix at The Glen |

| DPi | 1:29.657[14] | Olivier Pla | Mazda RT24-P | 2019 6 Hours of The Glen |

| LMP2 | 1:32.444[15] | Giedo van der Garde | Oreca 07 | 2022 6 Hours of The Glen |

| Indy Lights | 1:33.6921[16] | Dean Stoneman | Dallara IL-15 | 2016 Watkins Glen Indy Lights round |

| DP | 1:34.515[17] | Olivier Pla | Ligier JS P2 | 2016 6 Hours of The Glen |

| LMPC | 1:37.300[17] | Renger van der Zande | Oreca FLM09 | 2016 6 Hours of The Glen |

| IMSA GTP | 1:39.011[18] | Juan Manuel Fangio II | Eagle MkIII | 1993 Fay's Drugs Weekend at the Glen |

| LMP900 | 1:39.200[19] | Oliver Gavin | Lola B2K/10 | 2000 6 Hours of The Glen |

| WSC | 1:39.617[20] | Didier Theys | Ferrari 333 SP | 2001 6 Hours of The Glen |

| LMP3 | 1:39.967[21] | Colin Braun | Ligier JS P320 | 2021 WeatherTech 240 at The Glen |

| LM GTE | 1:41.563[14] | Antonio García | Chevrolet Corvette C7.R | 2019 6 Hours of The Glen |

| Pro Mazda | 1:43.573[22] | Victor Franzoni | Star Formula Mazda 'Pro' | 2017 Watkins Glen Pro Mazda round |

| GT1 (Prototype) | 1:43.580[23] | Thierry Boutsen | Porsche 911 GT1 Evo | 1998 First Union 6 Hours of The Glen |

| GT3 | 1:44.286[24] | Álvaro Parente | Bentley Continental GT3 | 2019 Watkins Glen GT World Challenge America round |

| LMP675 | 1:45.460[25] | Ralf Kelleners | Lola B2K/40 | 2002 6 Hours of The Glen |

| US F2000 | 1:46.785[26] | Rinus VeeKay | Tatuus USF-17 | 2017 Watkins Glen US F2000 round |

| GT1 (GTS) | 1:47.717[27] | Jean-Philippe Belloc | Chrysler Viper GTS-R | 1999 FIA GT Watkins Glen 3 Hours |

| IMSA GTP Lights | 1:48.300[18] | Parker Johnstone | Spice SE90P | 1993 Fay's Drugs Weekend at the Glen |

| Ferrari Challenge | 1:48.418[28] | Cooper MacNeil | Ferrari 488 Challenge Evo | 2021 Watkins Glen Ferrari Challenge North America round |

| IMSA GTS | 1:48.833[18] | Darin Brassfield | Oldsmobile Cutlass | 1993 Fay's Drugs Weekend at the Glen |

| American GT | 1:50.700[19] | Irv Hoerr | Chevrolet Camaro | 2000 6 Hours of The Glen |

| N-GT | 1:51.317[29] | John O'Steen | Porsche 911 GT2 | 1999 FIA GT Watkins Glen 3 Hours |

| GTO | 1:51.800[19] | Cort Wagner | Porsche 911 GT2 (996) | 2000 6 Hours of The Glen |

| GTU | 1:54.000[19] | David Murry | Porsche 911 GT3-R (996) | 2000 6 Hours of The Glen |

| GT4 | 1:54.077[30] | Devin Jones | BMW M4 GT4 | 2019 Tioga Downs Casino Resort 240 at The Glen |

| TCR Touring Car | 1:57.085[31] | Jonathan Morley | Audi RS 3 LMS TCR | 2021 Watkins Glen 120 |

| IMSA GTO | 1:57.100[32] | Brian DeVries | Oldsmobile Cutlass | 1994 The Glen Continental |

| IMSA GTU | 2:01.420[18] | Butch Leitzinger | Nissan 240SX | 1993 Fay's Drugs Weekend at the Glen |

| IMSA Supercar | 2:12.099[33] | Hans-Joachim Stuck | Porsche 911 Turbo (964) | 1993 Fay's Drugs Weekend at the Glen |

| Short Circuit (with Inner Loop Chicane): 3.943 km (1992–present) | ||||

| IMSA GTP | 59.920[34] | Davy Jones | Jaguar XJR-14 | 1992 Camel Continental |

| LMP900 | 1:03.676[35] | Didier Theys | Dallara SP1 | 2002 Bully Hill Vineyards 250 |

| DP | 1:05.349[36] | Scott Pruett | Riley MkXX | 2010 Crown Royal 200 at The Glen |

| LMP675 | 1:08.499[37] | Bruno St. Jacques | Lola B2K/40 | 2001 Bully Hill Vineyards 250 |

| IMSA GTP Lights | 1:09.020[34] | Parker Johnstone | Spice SE91P | 1992 Camel Continental |

| NASCAR Cup | 1:10.540[38] | Martin Truex Jr. | Toyota Camry | 2019 Go Bowling at The Glen |

| GT1 (GTS) | 1:10.939[37] | Ron Johnson | Saleen S7-R | 2001 Bully Hill Vineyards 250 |

| American GT | 1:11.899[35] | Chris Bingham | Chevrolet Corvette | 2002 Bully Hill Vineyards 250 |

| NASCAR Xfinity | 1:12.094[39] | William Byron | Chevrolet Camaro SS | 2022 Sunoco Go Rewards 200 at The Glen |

| GT | 1:13.541[35] | Bill Auberlen | Ferrari 360 GT | 2002 Bully Hill Vineyards 250 |

| NASCAR Truck | 1:14.933[40] | Austin Hill | Toyota Tundra | 2021 United Rentals 176 at The Glen |

| IMSA Supercar | 1:23.651[41] | Shawn Hendricks | Nissan 300ZX | 1994 Glen Contiental |

| Short Circuit (with Esses Chicane): 3.907 km (1979–1991) | ||||

| IMSA GTP | 59.920[42] | Davy Jones | Jaguar XJR-16 | 1991 Camel Continental |

| IMSA GTP Lights | 1:07.060[42] | Parker Johnstone | Spice SE90P | 1991 Camel Continental |

| IMSA Supercar | 1:21.350[43] | Hurley Haywood | Porsche 911 Turbo (964) | 1991 Camel Continental |

| Grand Prix Circuit: 5.435 km (1971–1974, 1986–present)[2] | ||||

| IMSA GTP | 1:35.600[44] | Chip Robinson | Nissan NPT-90 | 1990 Camel Continental |

| Group 7 | 1:39.571[45] | Mark Donohue | Porsche 917/30 TC | 1973 Watkins Glen Can-Am round |

| Formula One | 1:40.608 | Carlos Pace | Brabham BT44 | 1974 United States Grand Prix |

| Group 5 | 1:43.847[46] | François Cevert | Matra-Simca MS670B | 1973 Watkins Glen 6 Hours |

| IMSA GTP Lights | 1:45.100[44] | Ruggero Melgrati | Spice SE89P | 1990 Camel Continental |

| IMSA GTO | 1:47.150[47] | Hans-Joachim Stuck | Audi 90 Quattro | 1990 Kodak Copier 500 |

| IMSA GTU | 1:56.050[47] | Bob Leitzinger | Nissan 240SX | 1990 Kodak Copier 500 |

| IMSA AAC | 1:56.550[48] | Ray Kong | Oldsmobile Cutlass | 1991 Camel Continental |

| Trans-Am | 1:58.300[49] | Peter Gregg | Porsche Carrera RSR | 1974 Watkins Glen Trans-Am round |

| Grand Prix Circuit with Esses Chicane: 5.435 km (1975–1985)[2] | ||||

| Formula One | 1:34.068 | Alan Jones | Williams FW07B | 1980 United States Grand Prix |

| IMSA GTP | 1:40.260[50] | Klaus Ludwig | Ford Mustang Probe | 1985 Serengeti Drivers New York 500 |

| Can-Am | 1:40.746[51] | Geoff Brabham | Lola T530 | 1981 Watkins Glen Can-Am round |

| Group 6 | 1:45.956[52] | Gérard Larrousse | Alpine-Renault A442 Turbo | 1975 Watkins Glen 6 Hours |

| IMSA GTO | 1:51.380[50] | Darin Brassfield | Ford Thunderbird | 1985 Serengeti Drivers New York 500 |

| IMSA GTP Lights | 1:52.400[53] | Bill Alsup | Royale RP40 | 1985 Camel Continental |

| Group 5 | 1:52.831[54] | John Paul Jr. | Porsche 935 JLP-3 | 1981 Watkins Glen 6 Hours |

| Trans-Am | 1:54.402[55] | Wally Dallenbach Jr. | Chevrolet Camaro | 1984 Watkins Glen Trans-Am round |

| IMSA GTU | 2:00.370[56] | Elliot Forbes-Robinson | Porsche 924 Carrera | 1985 Camel Continental |

| Sports Car Circuit: 3.911 km (1971)[2] | ||||

| Group 7 (Can-Am) | 1:06.083[57] | Denny Hulme | McLaren M8F | 1971 Watkins Glen Can-Am round |

| Group 5 | 1:08.297[58] | Derek Bell | Porsche 917K | 1971 Watkins Glen 6 Hours |

| Trans-Am | 1:18.196[59] | George Follmer | Ford Mustang Boss 302 | 1971 Watkins Glen Trans-Am round |

| Original Grand Prix Circuit: 3.782 km (1956–1970)[2] | ||||

| Group 7 (Can-Am) | 1:02.600[60] | Denny Hulme | McLaren M8B | 1969 Watkins Glen Can-Am round |

| Formula One | 1:02.740 | Jacky Ickx | Ferrari 312B | 1970 United States Grand Prix |

| Group 5 | 1:04.900[61] | Pedro Rodríguez | Porsche 917K | 1970 Watkins Glen 6 Hours |

| Group 6 | 1:09.130[62] | Vic Elford | Porsche 908/02 | 1969 Watkins Glen 6 Hours |

| Group 4 | 1:11.100[63] | Jacky Ickx | Ford GT40 | 1968 Watkins Glen 6 Hours |

| Trans-Am | 1:14.650[64][65] | Parnelli Jones | Ford Mustang Boss 302 | 1970 Watkins Glen Trans-Am round |

| Stock car racing | 1:22.762[66] | Billy Wade | Mercury Marauder | 1964 The Glen 151.8 |

| Group 3 | 1:24.800[67] | Ken Miles | Shelby Cobra | 1964 Watkins Glen Sports Car Grand Prix |

| Second Public Road Course: 7.403 km (1953–1955) | ||||

| Sports car | 3:10.800[68] | Bill Spear | Ferrari 375 MM | 1954 Watkins Glen Grand Prix |

| Original Public Road Course: 10.622 km (1948–1952) | ||||

| Formula Libre | 5:13.500[69] | Phil Walters[70] | Healey-Cadillac Special | 1950 Watkins Glen Grand Prix |

Records

| Category | Driver(s) | Date | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIA Formula One Qualifying (GP Course) | Bruno Giacomelli | 1980 | 1:33.291 (130.315 mph; 209.722 km/h) |

| FIA Formula One Race (199.24 miles; 318.784 km) | Alan Jones | 1980 | 1:34:36 (126.367 mph; 203.368 km/h) |

| FIA Formula One Qualifying (2.35–mile course) | Jacky Ickx | 1970 | 1:03.07 (134.136 mph; 214.617 km/h) |

| FIA Formula One Race (253.8 miles; 408.2 km) | Emerson Fittipaldi | 1970 | 1:57:33.2 (129.541 mph; 207.265 km/h) |

| NASCAR Cup Series Qualifying | Marcos Ambrose | 2014 | 1:08.113 seconds (129.491 mph; 208.355 km/h)[71] |

| NASCAR Cup Series Race (220.5 miles; 354.860 km) | Martin Truex Jr. | 2017 | 2:26:17 (104.132 mph; 167.584 km/h) |

| NASCAR Xfinity Series Qualifying | William Byron | 2022 | 1:10.548 (125.021 mph; 197.266 km/h) |

| NASCAR Xfinity Series Race (200.9 miles; 323.317 km) | Terry Labonte | 1996 | 2:11:47 (91.468 mph; 146.348 km/h) |

| World Sportscar Championship (qualifying) | Brian Redman | 1970 | 1:06.3 |

| World Sportscar Championship (fastest lap) | Pedro Rodriguez | 1970 | 1:04.9 |

| FIA GT Championship (qualifying) | Olivier Beretta | 1999 | 1:47.576 |

| FIA GT Championship (fastest lap) | Olivier Beretta | 1999 | 1:47.717 |

| IndyCar Series Qualifying (GP Course) | Scott Dixon | 2017 | 1:22.4171 (147.202 mph; 236.898 km/h) |

| Indy Lights Qualifying (GP Course) | Santiago Urrutia | 2016 | 131.278 mph (211.271 km/h) |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Qualifying (DPi, GP Course) | Tom Blomqvist | 2022 | 1:29.580 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Qualifying (P, GP Course) | Luis Felipe Derani | 2017 | 1:34.405 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Qualifying (LMP2, GP Course) | Ben Keating | 2022 | 1:33.930 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Qualifying (PC, GP Course) | James French | 2017 | 1:40.049 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Qualifying (LMP3, GP Course) | Nicolás Varrone | 2022 | 1:40.028 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Qualifying (GTLM, GP Course) | Antonio García | 2021 | 1:40.944 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Qualifying (GTD, GP Course) | Jack Hawksworth | 2021 | 1:45.081 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Fastest Race Lap (DPi, GP Course) | Olivier Pla | 2019 | 1:29.657 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Fastest Race Lap (LMP2, GP Course) | Gabriel Aubry | 2021 | 1:32.918 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Fastest Race Lap (LMP3, GP Course) | Colin Braun | 2021 | 1:39.967 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Fastest Race Lap (GTLM, GP Course) | Antonio García | 2019 | 1:41.563 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Fastest Race Lap (GTD, GP Course) | Jack Hawksworth | 2017 | 1:44.786 |

| IMSA WeatherTech Championship Race (6 Hours, GP Course) | João Barbosa/Christian Fittipaldi/Felipe Albuquerque | 2017 | 200 laps, 680 mi (112.922 mph; 181.730 km/h) |

| Grand Am Rolex Sports Car Series (Short Course) Qualifying | Jon Fogarty | 2007 | 1:07.020 (131.603 mph; 211.794 km/h) |

| Grand-Am Crown Royal 200 at the Glen | Brian Frisselle | 2008 | 1:05.243[72] |

| Barber Saab Pro Series Qualifying (2.35–mile course) | Rino Mastronardi | 1997 | 1:15.041 |

| Barber Saab Pro Series Race | Derek Hill | 1997 | 1:15.296 |

| Atlantic Championship Race | Jimmy Simpson | 2014 | 1:40.634 |

NASCAR Cup Series records

| Most wins | 5 | Tony Stewart |

| Most top 5s | 12 | Mark Martin |

| Most top 10s | 16 | |

| Starts | 24 | Jeff Gordon |

| Poles | 4 | Jeff Gordon |

| Most laps completed | 2,075 | Jeff Gordon |

| Most laps led | 262 | Jeff Gordon |

| Avg. start* | 5.9 | Tony Stewart |

| Avg. finish* | 8.9 | Carl Edwards |

* from minimum 10 starts.

Deaths

See also

- List of Formula One circuits

- List of Champ Car circuits

- List of NASCAR race tracks

References

- "Watkins Glen International Track News, Records & Links". jayski.com. jayski.com. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- "Watkins Glen". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Santelli, Robert (1980). Aquarius Rising. New York: Dell. ISBN 978-0-440-50956-1., cited in Strycharz, Robb. "Watkins Glen "Summer Jam" Archive". Chronos. Archived from the original on 2 August 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Map of Original Watkins Glen Grand Prix Circuit, 1948 - 1952". www.grandprixfestival.com. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- 70 years of the SCCA - Racer Magazine, 30 January 2014

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "NASCAR may get 'the Boot' at Watkins Glen". nascar.com. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- "Watkins Glen Loses Race; Track Failed to Pay Debts". The New York Times. AP. 8 May 1981. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Nashville Network to carry race at Watkins Glen". Star-Gazette. Elmira, New York. June 21, 1984. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- Bandoim, Lana (2012-10-31). "Hurricane Sandy Affects NASCAR: Fan View". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- Reid Spencer. "NASCAR may get 'the Boot' at Watkins Glen". NASCAR.com. NASCAR Media Group, LLC. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- Swansey, Jack (2022-08-19). "(Don't) Run The Boot". www.frontstretch.com. Retrieved 2022-10-28.

- Cavin, Curt (May 13, 2016). "IndyCar series to race at Watkins Glen". The Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- "2019 Sahlen's Six Hours at The Glen Race Official Results" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "2022 Sahlen's Six Hours at The Glen Race Unofficial Results" (PDF). Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- "2016 Watkins Glen Indy Lights". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "2016 Sahlen's Six Hours at The Glen Race Official Results" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 500 Kilometres 1993". Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 2000". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 2001". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "WeatherTech 240 at The Glen Race Official Results (2 Hours 40 Minutes)" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "2017 Watkins Glen Pro Mazda Race 1 Statistics". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 1998". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "2019 Watkins Glen Blancpain GT World Challenge America RACE 1 - Classification - Final" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 2002". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "2017 Watkins Glen US F2000 Race Statistics". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "FIA GT Championship Watkins Glen 1999". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "2021 Ferrari Challenge North America Trofeo Pirelli Watkins Glen Race 2 Official Results (30 Minutes)" (PDF). Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- "I Watkins Glen 3 hours". Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- "2019 Tioga Downs Casino Resort 240 at The Glen Race Official Results (4 Hours)" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "2021 Watkins Glen 120 Race Official Results (2 Hours)" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 3 Hours 1994". Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- "IMSA Supercar Watkins Glen 1993". Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- "IMSA GTP Watkins Glen 1992". Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 250 Miles 2002". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "2010 Watkins Glen Grand-Am - Round 10". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 250 Miles 2001". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "NASCAR Cup 2019 Watkins Glen". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "NASCAR Xfinity 2022 Watkins Glen Statistics". Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- "NASCAR Truck 2021 Watkins Glen". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "IMSA Supercar Watkins Glen 1994". Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 500 Kilometres 1991". Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- "IMSA Supercar Watkins Glen 1991". Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 500 Kilometres 1990". Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- "Can-Am Watkins Glen 1973". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 1973". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 500 Kilometres 1989". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 500 Kilometres - Grand Touring 1991". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 1974". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 500 Kilometres".

- "Can-Am Watkins Glen 1981". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 1975". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 3 Hours 1985". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 1981". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Trans-Am Watkins Glen 1984". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 1984". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Can-Am Watkins Glen 1971". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 1971". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Trans-Am Watkins Glen 1971". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Can-Am Watkins Glen 1969". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 1970". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 1969". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen 6 Hours 1968". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "1970 Trans-Am - round 9 - Watkins Glen Trans-Am race". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Trans-Am Watkins Glen 1970". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "1964 THE GLEN 151.8". Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- "USRRC Watkins Glen - GT Race 1964". Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- "Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1954". Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- "Watkins Glen Grand Prix - Seneca Cup 1950". Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Ted Tappett's legend lives--Watkins Glen inducts Phil Walters as a 'driver of the decade'". 23 September 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Marcos Ambrose wins Cup pole". ESPN. Associated Press. 2013-08-10. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- "Frisselle, AIM Autosport to Start from Pole in Crown Royal 200". theglen.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

External links

- Watkins Glen International

- Watkins Glen International race results at Racing-Reference

- Short History of Road Racing at Watkins Glen

- GP Encyclopedia, Circuits: Watkins Glen

- Trackpedia guide to driving this track

- Watkins Glen International Page on NASCAR.com

- Watkins Glen Grand Prix Fest

- Track history and other info

- 1948–1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Circuit Map

- Photos from past and present events at Watkins Glen International

- Race Services Inc. The organization for the course workers at WGI