Circuit de Monaco

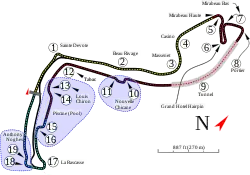

Circuit de Monaco is a 3.337 km (2.074 mi) street circuit laid out on the city streets of Monte Carlo and La Condamine around the harbour of the Principality of Monaco. It is commonly, and even officially,[1] referred to as "Monte Carlo" because it is largely inside the Monte Carlo neighbourhood of Monaco.

| |

| Location | La Condamine and Monte Carlo, Monaco |

|---|---|

| Time zone | Central European time |

| Coordinates | 43°44′5″N 7°25′14″E |

| Capacity | 37,000 |

| FIA Grade | 1 (GP) 3E (Formula E) |

| Opened | 14 April 1929 |

| Major events | Current: Formula One Monaco Grand Prix (1950, 1955–2019, 2021–present) Formula E Monaco ePrix (biennial 2015–2019, 2021–present) FIA F2 (2017–2019, 2021–present) FREC (2021–present) Historic Grand Prix of Monaco (1997, biennial 2000–2018, 2021–present) Porsche Supercup (1993–2019, 2021–present) Future: FIA F3 (2023) Former: Jaguar I-Pace eTrophy (2019) GP2 (2005–2016) GP3 (2012) Formula Renault Eurocup (2016–2019) World Series by Renault (2005–2015) F3 Euro Series (2005) F3000 (1998–2004) European Formula 3 (1975) |

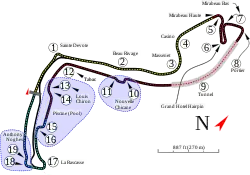

| Grand Prix Circuit (2015–present) (Tabac slightly moved) | |

| Length | 3.337 km (2.074 miles) |

| Turns | 19 |

| Race lap record | 1:12.909 ( |

| Extended Formula E Circuit (2021) (changes in Nouvelle Chicane) | |

| Length | 3.318 km (2.062 miles) |

| Turns | 19 |

| Race lap record | 1:34.428 ( |

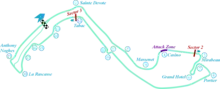

| Original Formula E Circuit (2015–2019) | |

| Length | 1.765 km (1.097 miles) |

| Turns | 12 |

| Race lap record | 0:52.385 ( |

| 6th Variation (2003–2014) (tightened, slower chicane at exit of swimming pool section) | |

| Length | 3.340 km (2.075 miles) |

| Turns | 19 |

| Race lap record | 1:14.439 ( |

| 5th Variation (1997–2002) (redesigned swimming pool section) | |

| Length | 3.370 km (2.094 miles) |

| Turns | 18 |

| Race lap record | 1:18.023 ( |

| 4th Variation (1986–1996) (Nouvelle chicane added) | |

| Length | 3.328 km (2.068 miles) |

| Turns | 20 |

| Race lap record | 1:21.076 ( |

| 3rd Variation (1976–1985) (using tighter curves of Sainte Devote and Anthony Noghes) | |

| Length | 3.312 km (2.058 miles) |

| Turns | 20 |

| Race lap record | 1:22.637 ( |

| 2nd Variation (1973–1975) (redesigned with new tunnel, swimming pool section) | |

| Length | 3.278 km (2.037 miles) |

| Turns | 17 |

| Race lap record | 1:27.900 ( |

| 1st Variation (1972) (chicane in the port moved further away from the tunnel) | |

| Length | 3.145 km (1.954 miles) |

| Turns | 13 |

| Race lap record | 1:32.700 ( |

| Original Circuit (1929–1971) | |

| Length | 3.145 km (1.954 miles) |

| Turns | 14 |

| Race lap record | 1:22.200 ( |

The circuit is annually used on three weekends in April–May for Formula One Monaco Grand Prix, Formula E Monaco ePrix and Historic Grand Prix of Monaco. Formula One's respective feeder series over the years – Formula 3000, GP2 Series and today the Formula 2 championship and Porsche Supercup – also visit the circuit concurrently with Formula One. The Monaco Grand Prix is one of the three events victories in which count towards the Triple Crown of Motorsport.

History

The idea for a Grand Prix race around the streets of Monaco came from Antony Noghès, the president of the Monegasque motor club, Automobile Club de Monaco, and close friend of the ruling Grimaldi family. The inaugural race was held in 1929 and was won by William Grover-Williams in a Bugatti.

To date, only three local drivers have won a race at the circuit. Louis Chiron did it at the non-championship 1931 Monaco Grand Prix; 82 years later, Stefano Coletti crossed the line in first position at the sprint race of the 2013 Monaco GP2 Series round. The third driver to do so was Stéphane Richelmi at the sprint race of the 2014 Monaco GP2 Series round.

Evolution of the circuit

The track has remained substantially unchanged since its creation in 1929: as a city circuit, its conformation is closely linked to that of the principality's road system. The changes were almost entirely connected to redefinitions of the ordinary roads of the town.

In the first editions of the Grand Prix, the start and finish were placed on Boulevard Albert 1er (the innermost straight, which leads to the Sainte Dévote curve). In 1955 the start and finish were moved to the opposite straight, overlooking the promenade (that now houses the pit lane). At the time, neither the Piscine complex nor the "La Rascasse" hairpin existed: after the "Tabac" curve, the route proceeded in the lane that is parallel to today's starting straight: the two sections (separated only by a row of trees) were joined by a single narrow hairpin called the "Gasometer". As can be seen from the period films, in the second half of the 1950s the only existing lane after the Tabac was the one mentioned; in fact, in those years, the lane that we now call "promenade" with the two "Piscine" chicanes was not yet defined, and only in the 1960s images we can notice the progress of the landfilling about that portion of the bay, including the Piscine area which will be completed shortly thereafter.

In 1963 the starting line was again moved to Boulevard Albert 1er (opposite the promenade), without changes to the track from the "Tabac" to the "Gasometer" (incidentally, the swimming pool and the waterfront lane that 10 years later will become part of the circuit, had already been created).

In 1972 the boxes were moved near the chicane area of the port, therefore was created a "new" chicane that was closer to the "Tabac" curve. After this chicane, the track continued on the usual straight (parallel to the starting lane) using the "Gasometer" curve for the last time. This solution lasted only a year and, in the following months, the main works were completed in time for the 1973 Grand Prix with the construction of a new section that still connects the "Tabac" curve to "Piscine" (Stade Nautique). This change will result in the addition of 0.133 km (0.083 mi) to the circuit – whose total length increased to 3.278 km (2.037 mi) – adding the new portion along the harbour, which followed the layout of the swimming pool and ended in a new chicane around the "La Rascasse" restaurant and then joined (with a slight climb to the Anthony Noghes curve) to the starting straight. The boxes were reinstalled in the old lane (now free). The layout took on its current appearance with the double chicane "Piscine", abandoning (by the 1973 GP) the old "Gasometer" curve (where the entrance to the new boxes was created). 1972 was also the last year for the passage under the old tunnel.

In 1973, as anticipated, the track was modified at various points also due to the construction of new civil buildings. In particular, a new hotel was under construction in the "Old Station" hairpin area (Hotel Loews, later renamed Fairmont), resulting in an extension of the tunnel towards the "Portier" curve. The 1973 images show the unusual passage under the new long tunnel, above which the pillars of the Loews hotel are being built. At the exit of the tunnel there was the traditional port chicane and, after the "Tabac" curve, the new path adjacent to the swimming pools (two "S" left–right and right–left connected by a short straight) and "La Rascasse" hairpin. It was the first year for the new garages in an independent lane, with an entrance just after "La Rascasse", where an asphalt slide was installed to overcome the difference in level from the roadway.

In 1976 the "Sainte Dévote" and "Anthony Noghes" corners were modified: in order to slow down the transit of the cars, curbs and protections were repositioned.

In 1986, thanks to the expansion of the roadway implemented in the chicane area of the port, the chicane itself was modified and made slower: instead of the previously existing fast change of direction, deemed too dangerous, new curbs were installed to design a double turn at 90 degrees. It was then renamed "Nouvelle Chicane".

In 1997 the first "Piscine" corner was modified: the shifting of the track edge protections improved the visibility for the pilots and allowed a higher speed. A year later (at the request of Pasquale Lattuneddu, chief operating officer of Formula One Management), the whole area of the paddock was surrounded with shatterproof fences, in order to reduce and better manage the people authorised to access them.

In 2003 the second "Piscine" curve underwent a treatment similar to that of the first curve, with the shifting of the barriers to improve visibility, while the arrangement of new temporary curbs went to slow down the passage of the cars. However, the most important novelty was the widening of the port lane: in this way the segment between "Piscine" and "La Rascasse" could be rectified, becoming faster and less demanding. The extra space also allowed for the installation of new grandstands and the expansion of the pit lane, which was also equipped with semi-permanent two-storey buildings (instead of the previous tiny prefabricated structures) to better accommodate the teams, the technicians and the material.

Before the 2007 season, the internal curb of the "Grand Hotel" hairpin was significantly lowered and widened, in order to allow the single-seaters to climb on it and eventually face the curve with a narrower trajectory.

Since the 2003 edition, the traffic divider at the "Sainte Dévote" curve has been removed in order to widen the track: the track design is now left to the curb only. This has meant, for safety reasons, an extension of the exit lane from the pits: in practice, once the "proper" pit lane has been left, the drivers must remain in the yellow line that "cuts" the "Sainte Dévote".

The pit lane was further revised in 2004 by reversing the position of the pits with respect to the lane itself, building a much larger and more welcoming structure. Monte Carlo has thus become the only Formula 1 circuit in which the pits are not facing the track, but rather physically separate it from the pit lane.

In 2011, after some accidents that occurred during the race weekend (the Mexican driver Sergio Pérez suffered a rather serious one), the drivers urged a change in the sector between the exit of the tunnel and the "Nouvelle Chicane", complaining (above all) about the disconnection of the road surface and incorrect positioning of the guard rail in the escape route opposite the tunnel. However, these requests were not followed up.

In 2015 the "Tabac" curve was re-profiled, slightly anticipating the entrance and thus shortening the track by three metres (from 3.340 km (2.075 mi) to 3.337 km (2.074 mi) today).

Characteristics

The building of the circuit takes six weeks, and the dismantling after the race another three weeks. The race circuit is narrow, with many elevation shifts and tight corners. These features make it perhaps the most demanding track in Formula One racing. Although the course has changed many times during its history, it is still considered the ultimate test of driving skills in Formula One.[2] It contains both the slowest corner in Formula One (the Fairmont Hairpin, taken at just 48 km/h or 30 mph) and one of the quickest (the flat out kink in the tunnel, three turns beyond the hairpin, taken at 260 km/h or 160 mph).

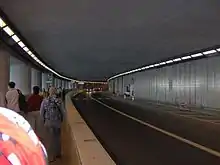

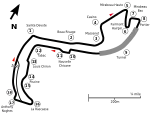

Due to the tight and twisty nature of the circuit, it favours the skill of the drivers over the power of the cars. However, there is very little overtaking as the course is so narrow and dangerous, as demonstrated by the 2021 Monaco Grand Prix having only one overtake in a 78 lap race (when Mick Schumacher overtook his teammate Nikita Mazepin on the opening lap). Nelson Piquet likened racing round the course to "riding a bicycle around your living room".[3] Prior to 1987, the number of cars starting the race was limited to 20, compared to 26 at other circuits. The famous tunnel section (running under the Fairmont Hotel, marked in grey in the circuit diagram above) is said to be difficult for drivers to cope with due to the quick switch from light to dark, then back to light again, at one of the fastest points of the course. As a result, race outcomes tend to be decided by grid positions as well as pit strategies, and the race is extremely hard on gearboxes and brakes.

Several attempts have been made to improve cramped conditions in the pit garages. In 2002, a substantial amount of land was reclaimed from the harbour to slightly change the shape of one section of the circuit; this left more space for new pit garages, which debuted in the 2004 event.

The circuit is generally recognized to be less safe than other circuits used for Formula One. Driver and former winner Michael Schumacher stated before the 2012 Grand Prix that the additional risk is "justifiable once a year".[4] If it were not already an existing Grand Prix, it would not be permitted to be added to the Formula One schedule, for safety reasons.[5]

In January 2009, the circuit was voted top of the "Seven Sporting Wonders of the World" in a poll of 3,500 British sports fans.[6]

A lap of the modern-day circuit

.jpg.webp)

The lap starts with a short sprint up Boulevard Albert Ier, to the tight Sainte-Dévote corner, named after Sainte-Dévote Chapel, a small church just beyond the barriers. This is a nearly 90-degree right-hand bend usually taken in first or second gear.[7] This corner has seen many first lap accidents, although these are less common since the removal of the mini roundabout on the apex of the corner before the 2003 event, making the entrance to the corner wider. The cars then head uphill along Avenue d'Ostende, before changing down for the long left-hander at Massenet. The maximum gradient in this part of the circuit is around 12%.

Out of Massenet, the cars drive past the famous casino, Monte Carlo Casino, before quickly reaching the aptly named Casino Square. This part of the track is 44 m (144 ft) higher than the lowest part. The cars snake down Avenue des Beaux Arts, the next short straight, avoiding an enormous bump on the left of the track, a reminder of the unique nature of the circuit. This leads to the tight Mirabeau corner, which is followed by a short downhill burst to the even tighter Fairmont Hairpin (was known as the Station Hairpin before the hotel was opened on the site in 1973; the hairpin's name changed depending on the name on the hotel).[8] It is a corner which has been used for many overtaking manoeuvres in the past. However, it would be almost physically impossible for two modern F1 cars to go round side by side, as the drivers must use full steering lock to get around. It is so tight that many Formula 1 teams must redesign their steering and suspension specifically to negotiate this corner.

After the hairpin, the cars head downhill again to a double right-hander called Portier, named after the region of Monaco, before heading into the famous tunnel, a unique feature of a Formula One circuit. (Until 2009 only one other circuit, Detroit in 1982–1988, featured a tunnel, but the F1 series now includes racing at the Yas Marina Circuit in Abu Dhabi, which presents a shorter tunnel at the exit of the pit lane.) As well as the change of light making visibility poor,[9] a car can lose 20–30% of its downforce due to the unique aerodynamic properties of the tunnel.[9] The tunnel also presents a unique problem when it rains. As it is virtually indoors, the tunnel usually remains dry while the rest of the track is wet, with only the cars bringing in water from their tyres. Famously before the very wet 1984 race, Formula One boss Bernie Ecclestone had local fire crews wet down the road in the tunnel to give it the same surface grip as the rest of the track. This was done at the request of McLaren driver Niki Lauda.

Out of the tunnel, the cars have to brake hard for the tight left–right–left Nouvelle Chicane. This has been the scene of several large accidents, including that of Karl Wendlinger in 1994, Jenson Button in 2003 and Sergio Pérez in 2011. The chicane is generally the only place on the circuit where overtaking can be attempted. There is a short straight to Tabac, so called as there used to be a tobacconist on the outside of the corner. Tabac is a tight fourth-gear corner which is taken at about 195 km/h (121 mph).[10] Accelerating up to 225 km/h (140 mph),[10] the cars reach Piscine, a fast left–right followed by a slower right–left chicane which takes the cars past the Rainier III Nautical Stadium, its swimming pool gives its name to the corner.

Following Piscine, there is a short straight followed by heavy braking for a quick left which is immediately followed by the tight 135-degree right-hander called La Rascasse. This is another corner that requires full steering lock; it will be remembered for a long time as the location of one of the most suspicious manoeuvres in recent Formula One history during the 2006 season when Michael Schumacher appeared to deliberately stop his car in qualifying so as to prevent Fernando Alonso and Mark Webber – who were both following and were on flying laps – from out-qualifying him. The Rascasse takes the cars into a short straight that precedes the final corner, Virage Antony Noghès. Named after the organiser of the first Monaco Grand Prix, the corner is a tight right-hander which brings the cars back onto the start-finish straight, and across the line to start a new lap.

Monaco is one of the three circuits which have only one DRS zone, the others being Suzuka and Imola. During the race, it is active along the pit straight from Antony Noghès to Sainte-Dévote, for a total of 510 m (560 yd).[11]

Mechanical adaptations

Monaco's street circuit places very different demands on the cars in comparison to the majority of the other circuits used during a Championship season. The cars are set up with high downforce; not as is popularly believed to increase cornering speeds, as many of the corners are taken at such a low speed to negate any aerodynamic effect, but instead to shorten braking times and keep the cars stable under acceleration.[12] Many teams use special wing assemblies incorporating extra active planes in addition to those in use for other circuits. The Jordan and Arrows teams tried to use new mid-wings in 2001. The Arrows wing was similar in design to a normal rear wing but smaller and suspended above the nose cone. Jordan had a small wing suspended on a short pole just in front of the driver. Both were designed to improve downforce, but, after testing them during Thursday practice, the FIA banned both.

Brake wear is not a problem during a race in Monaco. Instead, the low speeds mean the issue is keeping the brakes up to working temperature. The only heavy braking points are at the chicane after the tunnel, and to a lesser extent into the Sainte-Dévote and Mirabeau corners. With a lack of temperature, brake bite becomes a problem, as the surface of the carbon brake disc becomes smooth as glass, reducing friction between the pads and the disk, hence lessening braking power. To combat this, in 2006 Juan Pablo Montoya adopted discs with radial grooves that increased the bite rate between disk and pads, increasing the average temperature of the brakes.

Conversely, cooling the cars' engines is a major concern. Formula One cars do not incorporate any form of forced cooling, relying solely on air moving over the car to remove heat from the radiator elements. In the past many teams used to adjust the radiator intakes to allow for extra airflow, creating the once-common "Monaco nose". Before 2014, teams also used closer ratio gears, as there are hardly any long straights in Monaco and acceleration is at a premium (starting from the 2014 season, the same gear ratios must be used throughout the season). A special steering rack with a larger pinion gear is also fitted to allow the cars to be driven around the tightest corners.

In other motorsport

FIA World Rally Championship

The circuit has been used as a special stage during the WRC Monte Carlo Rally, for example in 2008.

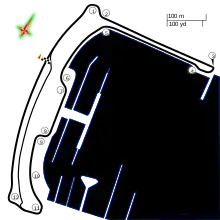

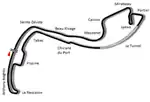

FIA Formula E Championship

On 18 September 2014 it was announced the Formula E would be racing on a shorter 1.760 km (1.094 mi) version of the Monaco Grand Prix circuit, which was subsequently used for the 2014–15, 2016–17 and 2018–19 seasons.[13] This layout omitted the regular section of the track between the climb up the hill at Beau Rivage and the Nouvelle Chicane at the exit of the tunnel, instead turning right immediately after Saint Devote to head downhill, before rejoining the regular layout by way of a 180 degree turn at the chicane.

Monaco was not scheduled to be on the calendar for the second season of Formula E because it took the slot on the calendar filled by the Historic Grand Prix at Monaco every other year. The inaugural Paris ePrix took its spot on the calendar for season two, with the Monaco ePrix reinstated for season three.[14] This biennial agreement will continue at least into Formula E's fifth season.[15]

A new track layout was used only for the 2021 Monaco ePrix: the layout is similar to the Formula One layout, with only slight differences at turns 1 (Sainte Devote) and 11 (Nouvelle Chicane). This new layout has a length of 3.318 km (2.062 mi); the distance of the track being increased due to the increase in car performance and range of Gen2 cars.[16] The 2022 Monaco ePrix would instead see the race run on the full track layout.

Events

- Current

- April: Formula E Monaco ePrix

- May: Formula One Monaco Grand Prix, FIA Formula 2 Championship, Formula Regional European Championship, Porsche Supercup, Historic Grand Prix of Monaco

- Former

- FIA European Formula 3 Championship (1975)

- Formula 3 Euro Series (2005)

- Formula Renault Eurocup (2016–2019)

- GP2 Series Monaco GP2 round (2005–2016)

- GP3 Series (2012)

- International Formula 3000 Monaco F3000 round (1998–2004)

- Jaguar I-Pace eTrophy (2019)

- World Series by Renault (2005–2015)

Criticism

Several commentators and drivers have criticised the circuit's design, saying that it creates boring races. Criticism has been directed towards how few overtake attempts are performed, the slow speeds at which the cars take the Fairmont Hairpin, as well as how frequently the driver who sets the pole position wins.[17][18][19] Fernando Alonso has said that the race is “the most boring race ever,” and Lewis Hamilton stated that the 2022 Grand Prix “wasn’t really racing.”[20][21]

Deaths from crashes

Major race results

Further information, see Monaco race results

Layout history and lap records

The layout history and official race lap records at the Circuit de Monaco are listed as:

| Circuit configuration | Circuit map | Class/category | Event | Time | Driver | Vehicle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Prix circuit (2015–present) (Tabac moved slightly) 3.337 km (2.074 mi) |

|

Formula One | 2021 Monaco Grand Prix | 1:12.909 | Mercedes-AMG F1 W12 E Performance | |

| GP2 | 2016 Monaco GP2 Series round | 1:21.554 | Dallara GP2/11 | |||

| Formula 2 | 2017 Monte Carlo Formula 2 round | 1:21.562 | Dallara GP2/11 | |||

| Formula Renault 3.5 Series | 2015 Monaco Formula Renault 3.5 Series round | 1:24.517[24] | Dallara T12 | |||

| FREC | 2022 Monte Carlo FREC round | 1:29.265[25] | Tatuus F.3 T-318 | |||

| Historic Formula One | 2022 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:30.946 | McLaren M23 | |||

| Formula Renault Eurocup | 2017 Monaco Formula Renault Eurocup round | 1:31.222[26] | Tatuus FR2.0/13 | |||

| Formula E | 2022 Monaco ePrix | 1:32.707 | Audi e-tron FE07 | |||

| Porsche Supercup | 2021 Monaco Porsche Supercup round | 1:34.118[27] | Porsche 911 (992) GT3 Cup | |||

| Historic Formula 2 | 2018 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:53.633 | Lotus 16 | |||

| Pre-war Grand Prix | 2022 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 2:00.103 | ERA R3A | |||

| Historic Sports Cars | 2022 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 2:00.286 | Cooper T38 (Mk2) | |||

| Extended Formula E circuit (2021) (changes in Nouvelle Chicane) 3.318 km (2.062 mi) |

|

Formula E | 2021 Monaco ePrix | 1:34.428 | Mercedes-EQ Silver Arrow 02 | |

| Short Formula E circuit (2015–2019) 1.765 km (1.097 mi) |

|

Formula E | 2019 Monaco ePrix | 0:52.385 | Mahindra M5Electro | |

| Jaguar I-Pace eTrophy | 2019 Monaco Jaguar I-Pace eTrophy round | 1:04.817[28] | Jaguar I-Pace eTrophy (racecar) | |||

| Grand Prix circuit (2003–2014) (tightened, slower chicane at exit of swimming pool section) 3.340 km (2.075 mi) |

|

Formula One | 2004 Monaco Grand Prix | 1:14.439 | Ferrari F2004 | |

| GP2 | 2008 Monaco GP2 Series round | 1:21.338 | Dallara GP2/08 | |||

| Formula Renault 3.5 Series | 2012 Monaco Formula Renault 3.5 Series round | 1:22.916[29] | Dallara T12 | |||

| F3000 | 2004 Monaco F3000 round | 1:26.911[30] | Lola B02/50 | |||

| Formula 3 | 2005 Monaco Grand Prix Formula Three | 1:28.017[31] | Dallara F305 | |||

| GP3 | 2012 Monaco GP3 Series round | 1:28.747 | Dallara GP3/10 | |||

| Historic Formula One | 2010 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:32.989 | McLaren M26 | |||

| Porsche Supercup | 2014 Monaco Porsche Supercup round | 1:37.616[32] | Porsche 911 GT3 Cup (991) | |||

| Historic Formula 3 2000cc | 2012 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:40.555 | Lola T670 | |||

| Historic Formula 2 | 2012 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:53.113 | Lotus 16 | |||

| Formula Junior | 2006 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:54.730 | Merlyn Mk5/7 | |||

| Historic Formula 3 1000cc | 2010 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:57.181 | Chevron B17 | |||

| Pre-war Grand Prix | 2014 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:59.058 | Alfa Romeo P3 | |||

| Historic Sports Cars | 2014 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:59.920 | Jaguar C-Type | |||

| Grand Prix circuit (1997–2002) (redesigned swimming pool section) 3.370 km (2.094 mi) |

|

Formula One | 2002 Monaco Grand Prix | 1:18.023 | Ferrari F2002 | |

| F3000 | 2002 Monaco F3000 round | 1:28.964[33] | Lola B02/50 | |||

| Formula 3 | 1997 Monaco Grand Prix Formula Three | 1:32.935[34] | Dallara F397 | |||

| Porsche Supercup | 2002 Monaco Porsche Supercup round | 1:43.903[35] | Porsche 911 GT3 Cup (996) | |||

| Historic Formula One | 2002 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:44.182 | Tyrrell 008 | |||

| Formula Junior | 2002 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 1:56.997 | Merlyn | |||

| Historic Sports Cars | 1997 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 2:02.703 | Maserati Tipo 61 | |||

| Pre-war Grand Prix | 2000 Historic Grand Prix of Monaco | 2:11.899 | Bugatti Type 35B | |||

| Grand Prix circuit (1986–1996) (Nouvelle Chicane added) 3.328 km (2.068 mi) |

|

Formula One | 1994 Monaco Grand Prix | 1:21.076 | Benetton B194 | |

| Formula 3 | 1996 Monaco Grand Prix Formula Three | 1:34.654[36] | Dallara F395 | |||

| Jaguar Intercontinental Challenge | 1991 Monaco Jaguar Intercontinental Challenge round | 1:48.642[37] | Jaguar XJR-15 | |||

| Grand Prix circuit (1976–1985) (using tighter curves of Sainte Devote and Anthony Noghes) 3.312 km (2.058 mi) |

|

Formula One | 1985 Monaco Grand Prix | 1:22.637 | Ferrari 156/85 | |

| Formula 3 | 1984 Monaco Grand Prix Formula Three | 1:33.617[38] | Ralt RT3 | |||

| Grand Prix circuit (1973–1975) (redesigned with new tunnel, swimming pool section) 3.278 km (2.037 mi) |

|

Formula One | 1974 Monaco Grand Prix | 1:27.900 | Lotus 72E | |

| Formula 3 | 1975 Monaco European F3 round | 1:34.600[39] | Modus M1 | |||

| Grand Prix circuit (1972) (chicane in the port moved further away from the tunnel) 3.145 km (1.954 mi) |

|

Formula 3 | 1972 Monaco Grand Prix Formula Three | 1:32.700[40] | Ensign LNF3/71 | |

| Formula One | 1972 Monaco Grand Prix | 1:40.000 | BRM P160B | |||

| Original Grand Prix circuit (1929–1971) 3.145 km (1.954 mi) |

|

Formula One | 1971 Monaco Grand Prix | 1:22.200 | Tyrrell 004 | |

| Formula 3 | 1969 Monaco Grand Prix Formula Three | 1:32.300[41] | Chevron B15 | |||

| Formula Junior | 1963 Monaco Grand Prix Formula Junior | 1:39.500[42] | Brabham BT6 |

Weather

The Monaco Grand Prix is run on the final Sunday of May, in a transition between spring and summer. Monaco, in general, has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa), although since the track is only used for a brief period in May, when it is being used it has a narrower temperature range than the principality itself has throughout the year. For the Monaco Grand Prix, temperatures are usually around 20 °C (68 °F) in terms of ambient conditions, whereas sun exposure can make the track itself a bit warmer than that. Still, soft tyre compounds often tend to hold up well around Monaco courtesy of surface temperatures being fairly moderate. The maritime moderation make May heatwaves rather unlikely.

Although the Mediterranean precipitation pattern leads to Monaco being quite dry by late May, due to the urban and narrow nature of the circuit, rainfall combined with the painted areas and the long tunnel makes wet racing extremely challenging. This was demonstrated by the 1984, 1996, 1997, 2008 and 2016 events. The 1984 event was red-flagged due to track conditions being deemed too dangerous with the race not being restarted. In 1996, the mixed-weather conditions caused carnage, paving way for Olivier Panis' shock win in an unfancied Ligier. The following year, the 1997 race winner Michael Schumacher got the chequered flag after just 62 of the planned 78 laps due to the very slow pace of half a minute slower than dry-weather lap times on the very wet track seeing the clock hit the two hours of maximum time well before the race distance was completed.

The tunnel can be sprinkled under wet conditions to provide for consistent track conditions, although during a full-wet race the tunnel gets drier throughout.

| Climate data for Monaco (1981–2010 averages, extremes 1966–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

23.2 (73.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

30.3 (86.5) |

32.5 (90.5) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.5 (94.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

29.0 (84.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

34.5 (94.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.9 (80.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.4 (61.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.4 (45.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

9.1 (48.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.2 (52.2) |

8.5 (47.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.5 (50.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 67.7 (2.67) |

48.4 (1.91) |

41.2 (1.62) |

71.3 (2.81) |

49.0 (1.93) |

32.6 (1.28) |

13.7 (0.54) |

26.5 (1.04) |

72.5 (2.85) |

128.7 (5.07) |

103.2 (4.06) |

88.8 (3.50) |

743.6 (29.28) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.0 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 62.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 149.8 | 158.9 | 185.5 | 210.0 | 248.1 | 281.1 | 329.3 | 296.7 | 224.7 | 199.0 | 155.2 | 136.5 | 2,574.7 |

| Source 1: Météo France[43] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Monaco website (sun only)[44] | |||||||||||||

See also

- The Chatham – a former bar near the Beau Rivage corner on the Circuit de Monaco that was popular with motor racing personalities

References

- In FIA official Formula 1 race documents, as well as in official broadcasts.

- "Monaco Grand Prix 2014: It's scary but cool. That's why it's the best track". telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- Widdows, Rob (24 May 2011). "Monaco challenge remains unique". Motor Sport. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- Benson, Andrew. "BBC Sport – Michael Schumacher says risk of racing at Monaco is "justifiable"". BBC. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Mansell, Nigel; Allsop, Derick (1989). In the Driving Seat: A Guide to the Grand Prix Circuits. Stanley Paul & Co. p. 32. ISBN 0-09-173818-0. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Monaco tops Seven Sporting Wonders". autosport.com. 29 January 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- Smith, B. (31 December 1995). Reliant Motors Formula 1 Annual. Words on Sport Limited. ISBN 978-1-898351-25-2. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Schleicher, Robert (3 November 2002). Slot Car Bible. Voyageur Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7603-1153-0. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- In The Driving Seat, Page 42

- In The Driving Seat, Page 43

- "McLaren Formula 1 – 2016 Monaco Grand Prix preview". mclaren.com. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- "Monaco – a Formula One set-up guide". www.formula1.com. 19 May 2009. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2018. [aerodynamics section]

- "Formula E set to race on shorter version of Monaco circuit". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- Smith, Topher (2 July 2016). "Season three calendar officially confirmed". e-racing.net.

- Smith, Sam (2 March 2018). "Full Monaco Grand Prix Circuit to Be Used in 2019". www.e-racing365.com. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- "Formula E, FIA and ACM reveal new track layout for Monaco E-Prix". 16 April 2021.

- Oliver Harden (22 May 2014). "Why the Monaco Grand Prix Is F1's Most Boring Race | News, Scores, Highlights, Stats, and Rumors". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Clancy, Rebecca. "Formula One: 'Boring' Monaco GP at risk of being downgraded to a biennial event". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- Brown, Oliver (20 May 2021). "The Monaco Grand Prix is the most boring race on the F1 circuit - only money gives it meaning". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- "Lewis Hamilton's damning rant on 'boring' Monaco GP: 'Thank god that's over' | F1 | Sport | Express.co.uk". www.express.co.uk. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- "Alonso says Monaco GP "the most boring F1 race ever"". us.motorsport.com. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- Biswas, Sabyasachi (28 August 2021). "Ranking the Top 10 Most Risky f1 Circuits in the World". 7up Sports. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- David Hayhoe; David Holland; Steve Rider (29 March 2006). Grand Prix Data Book: A Complete Statistical Record of the Formula 1 World Championship Since 1950. Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84425-223-7. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "2015 Monaco Formula Renault 3.5 Race Statistics". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "2022 Monaco FREC Race 2 Statistics". Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- "2017 Monaco Formula Renault Eurocup Race 2 Statistics". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "2021 Monaco Porsche Supercup Race Statistics". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "Jaguar I-PACE eTROPHY Series Round 7 - Monaco ePrix Race (25' +1 Lap) Final Classification". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "2012 Monaco Formula Renault 3.5 Race Statistics". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "2004 Monaco F3000". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "2005 Monaco F3". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "Champagne shower for Kuba Giermaziak in Monaco". Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- "2002 Monaco F3000". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "39e Grand Prix de Monaco F3 Ergebnis Rennen" (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- "2002 Porsche Supercup". Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- "38e Grand Prix de Monaco F3 Ergebnis Rennen" (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- "Jaguar Challenge Monaco 1991". Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- "26e Grand Prix de Monaco F3 Ergebnis Rennen" (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- "1975 Monaco F3". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "14e Grand Prix de Monaco F3 Ergebnis Vorlauf 1" (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- "11e Grand Prix de Monaco F3 Ergebnis Finalrennen" (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- "5e Grand Prix de Monaco Formula Junior Ergebnis Finalrennen" (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- "Monaco (99)" (PDF). Fiche Climatologique: Statistiques 1981–2010 et records (in French). Meteo France. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Climatological information for Monaco" (in French). Monaco Tourist Authority. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.