Wild boar

The wild boar (Sus scrofa), also known as the wild swine,[3] common wild pig,[4] Eurasian wild pig,[5] or simply wild pig,[6] is a suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The species is now one of the widest-ranging mammals in the world, as well as the most widespread suiform.[4] It has been assessed as least concern on the IUCN Red List due to its wide range, high numbers, and adaptability to a diversity of habitats.[1] It has become an invasive species in part of its introduced range. Wild boars probably originated in Southeast Asia during the Early Pleistocene[7] and outcompeted other suid species as they spread throughout the Old World.[8]

| Wild boar Temporal range: Early Pleistocene–Holocene | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Male Central European boar (S. s. scrofa) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Suidae |

| Genus: | Sus |

| Species: | S. scrofa |

| Binomial name | |

| Sus scrofa | |

| |

| Reconstructed range of wild boar (green) and introduced populations (blue): Not shown are smaller introduced populations in the Caribbean, New Zealand, sub-Saharan Africa, and elsewhere in Bermuda, North, Northeast, and Northwest Canada and Alaska.[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Species synonymy[2]

| |

As of 1990, up to 16 subspecies are recognized, which are divided into four regional groupings based on skull height and lacrimal bone length.[2] The species lives in matriarchal societies consisting of interrelated females and their young (both male and female). Fully grown males are usually solitary outside the breeding season.[9] The wolf is the wild boar's main predator in most of its natural range except in the Far East and the Lesser Sunda Islands, where it is replaced by the tiger and Komodo dragon respectively.[10][11] The wild boar has a long history of association with humans, having been the ancestor of most domestic pig breeds and a big-game animal for millennia. Boars have also re-hybridized in recent decades with feral pigs; these boar–pig hybrids have become a serious pest wild animal in the Americas and Australia.

Terminology

As true wild boars became extinct in Great Britain before the development of Modern English, the same terms are often used for both true wild boar and pigs, especially large or semi-wild ones. The English boar stems from the Old English bar, which is thought to be derived from the West Germanic bairaz, of unknown origin.[12] Boar is sometimes used specifically to refer to males, and may also be used to refer to male domesticated pigs, especially breeding males that have not been castrated.

Sow, the traditional name for a female, again comes from Old English and Germanic; it stems from Proto-Indo-European, and is related to the Latin: sus and Greek hus, and more closely to the New High German Sau. The young may be called piglets or boarlets.[13]

The animals' specific name scrofa is Latin for 'sow'.[14]

Hunting

In hunting terminology, boars are given different designations according to their age:[15]

| Designation | Age | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Squeaker | 0–10 months |  |

| Juvenile | 10–12 months | .jpg.webp) |

| Pig of the sounder | Two years | |

| Boar of the 4th/5th/6th year | 3–5 years |  |

| Old boar | Six years | |

| Grand old boar | Over seven years | _(cropped).jpg.webp) |

Taxonomy and evolution

MtDNA studies indicate that the wild boar originated from islands in Southeast Asia such as Indonesia and the Philippines, and subsequently spread onto mainland Eurasia and North Africa.[7] The earliest fossil finds of the species come from both Europe and Asia, and date back to the Early Pleistocene.[16] By the late Villafranchian, S. scrofa largely displaced the related S. strozzii, a large, possibly swamp-adapted suid ancestral to the modern S. verrucosus throughout the Eurasian mainland, restricting it to insular Asia.[8] Its closest wild relative is the bearded pig of Malacca and surrounding islands.[3]

Subspecies

As of 2005,[2] 16 subspecies are recognised, which are divided into four regional groupings:

- Western: Includes S. s. scrofa, S. s. meridionalis, S. s. algira, S. s. attila, S. s. lybicus and S. s. nigripes. These subspecies are typically high-skulled (though lybicus and some scrofa are low-skulled), with thick underwool and (excepting scrofa and attila) poorly developed manes.[17]

- Indian: Includes S. s. davidi and S. s. cristatus. These subspecies have sparse or absent underwool, with long manes and prominent bands on the snout and mouth. While S. s. cristatus is high-skulled, S. s. davidi is low-skulled.[17]

- Eastern: Includes S. s. sibiricus, S. s. ussuricus, S. s. leucomystax, S. s. riukiuanus, S. s. taivanus and S. s. moupinensis. These subspecies are characterised by a whitish streak extending from the corners of the mouth to the lower jaw. With the exception of S. s. ussuricus, most are high-skulled. The underwool is thick, except in S. s. moupinensis, and the mane is largely absent.[17]

- Indonesian: Represented solely by S. s. vittatus, it is characterised by its sparse body hair, lack of underwool, fairly long mane, a broad reddish band extending from the muzzle to the sides of the neck.[17] It is the most basal of the four groups, having the smallest relative brain size, more primitive dentition and unspecialised cranial structure.[18]

| Subspecies | Image | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central European boar S. s. scrofa Nominate subspecies |

.jpg.webp) |

Linnaeus, 1758 | A medium-sized, dark to rusty brown-haired subspecies with long and relatively narrow lacrimal bones[3] | Much of continental Europe and into Eurasia | anglicus (Reichenbach, 1846), aper (Erxleben, 1777), asiaticus (Sanson, 1878), bavaricus (Reichenbach, 1846), campanogallicus (Reichenbach, 1846), capensis (Reichenbach, 1846), castilianus (Thomas, 1911), celticus (Sanson, 1878), chinensis (Linnaeus, 1758), crispus (Fitzinger, 1858), deliciosus (Reichenbach, 1846), domesticus (Erxleben, 1777), europaeus (Pallas, 1811), fasciatus (von Schreber, 1790), ferox (Moore, 1870), ferus (Gmelin, 1788), gambianus (Gray, 1847), hispidus (von Schreber, 1790), hungaricus (Reichenbach, 1846), ibericus (Sanson, 1878), italicus (Reichenbach, 1846), juticus (Fitzinger, 1858), lusitanicus (Reichenbach, 1846), macrotis (Fitzinger, 1858), monungulus (G. Fischer [von Waldheim], 1814), moravicus (Reichenbach, 1846), nanus (Nehring, 1884), palustris (Rütimeyer, 1862), pliciceps (Gray, 1862), polonicus (Reichenbach, 1846), sardous (Reichenbach, 1846), scropha (Gray, 1827), sennaarensis (Fitzinger, 1858), sennaarensis (Gray, 1868), sennaariensis (Fitzinger, 1860), setosus (Boddaert, 1785), siamensis (von Schreber, 1790), sinensis (Erxleben, 1777), suevicus (Reichenbach, 1846), syrmiensis (Reichenbach, 1846), turcicus (Reichenbach, 1846), variegatus (Reichenbach, 1846), vulgaris (S. D. W., 1836), wittei (Reichenbach, 1846) |

| North African boar S. s. algira |

_(Sus_scrofa_algira).jpg.webp) |

Loche, 1867 | Sometimes considered a junior synonym of S. s. scrofa, but smaller and with proportionally longer tusks[19] | Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco | barbarus (Sclater, 1860) sahariensis (Heim de Balzac, 1937) |

| Carpathian boar S. s. attila |

|

Thomas, 1912 | A large-sized subspecies with long lacrimal bones and dark hair, though lighter-coloured than S. s. scrofa[3] | Romania, Hungary, Ukraine, the Balkans, the Caucasus, Transcaucasia, the Caspian coast, Asia Minor and northern Iran | falzfeini (Matschie, 1918) |

| Indian boar S. s. cristatus |

|

Wagner, 1839 | A long-maned subspecies with a coat that is brindled black unlike S. s. davidi,[20] it is more lightly built than S. s. scrofa. Its head is larger and more pointed than that of S. s. scrofa and its ears smaller and more pointed. The plane of the forehead is straight, while it is concave in S. s. scrofa.[21] | India, Nepal, Burma, western Thailand, Pakistan and Sri Lanka | affinis (Gray, 1847), aipomus (Gray, 1868), aipomus (Hodgson, 1842), bengalensis (Blyth, 1860), indicus (Gray, 1843), isonotus (Gray, 1868), isonotus (Hodgson, 1842), jubatus (Miller, 1906), typicus (Lydekker, 1900), zeylonensis (Blyth, 1851) |

| Central Asian boar S. s. davidi |

|

Groves, 1981 | A small, long-maned and light brown subspecies[20] | Pakistan and northwestern India to southeastern Iran | |

| Japanese boar S. s. leucomystax |

|

Temminck, 1842 | A small, almost maneless, yellowish-brown subspecies[20] | All of Japan, save for Hokkaido and the Ryukyu Islands | japonica (Nehring, 1885) nipponicus (Heude, 1899) |

| Anatolian boar S. s. libycus |

|

Gray, 1868 | A small, pale and almost maneless subspecies[20] | Transcaucasia, Turkey, Levant, and the former Yugoslavia | lybicus (Groves, 1981) mediterraneus (Ulmansky, 1911) |

| Maremman boar S. s. majori |

|

De Beaux and Festa, 1927 | Smaller than S. s. scrofa, with a higher and wider skull; since the 1950s, it has crossed extensively with S. s. scrofa, largely due to the two being kept together in meat farms and artificial introductions by hunters of S. s. scrofa specimens into S. s. majori habitats.[22] Its separation from S. s. scrofa is doubtful.[23] | Maremma (central Italy) | |

| Mediterranean boar S. s. meridionalis |

|

Forsyth Major, 1882 | The subspecies is significantly smaller than S. s. scrofa. The fur is dull olive-fawn, the underwool is sparse and individuals mostly lack a mane.[24] | Andalusia, Corsica and Sardinia | baeticus (Thomas, 1912) sardous (Ströbel, 1882) |

| Northern Chinese boar S. s. moupinensis |

_(6947132294).jpg.webp) |

Milne-Edwards, 1871 | There are significant variations within this subspecies and it is possible there are actually several subspecies involved.[20] | Coastal China south to Vietnam and west to Sichuan | acrocranius (Heude, 1892), chirodontus (Heude, 1888), chirodonticus (Heude, 1899), collinus (Heude, 1892), curtidens (Heude, 1892), dicrurus (Heude, 1888), flavescens (Heude, 1899), frontosus (Heude, 1892), laticeps (Heude, 1892), leucorhinus (Heude, 1888), melas (Heude, 1892), microdontus (Heude, 1892), oxyodontus (Heude, 1888), paludosus (Heude, 1892), palustris (Heude, 1888), planiceps (Heude, 1892), scrofoides (Heude, 1892), spatharius (Heude, 1892), taininensis (Heude, 1888) |

| Middle Asian boar S. s. nigripes |

Blanford, 1875 | A light coloured subspecies with black legs which, though varied in size, is generally quite large, the lacrimal bones and facial region of the skull are shorter than those of S. s. scrofa and S. s. attila.[3] | Middle Asia, Kazakhstan, the eastern Tien Shan, western Mongolia, Kashgar and possibly Afghanistan and southern Iran | ||

| Ryukyu boar S. s. riukiuanus |

|

Kuroda, 1924 | A small subspecies[20] | The Ryukyu Islands | |

| Trans-Baikal boar S. s. sibiricus |

Staffe, 1922 | The smallest subspecies of the former Soviet region, it has dark brown, almost black hair and a light grey patch extending from the cheeks to the ears. The skull is squarish and the lacrimal bones short.[3] | The Lake Baikal region, Transbaikalia, northern and northeastern Mongolia | raddeanus (Adlerberg, 1930) | |

| Formosan boar S. s. taivanus |

.JPG.webp) |

Swinhoe, 1863 | A small blackish subspecies[20] | Taiwan | |

| Ussuri boar S. s. ussuricus |

Heude, 1888 | The largest subspecies, it has usually dark hair and a white band extending from the corners of the mouth to the ears. The lacrimal bones are shortened, but longer than those of S. s. sibiricus.[3] | Eastern China, Ussuri and Amur Bay | canescens (Heude, 1888), continentalis (Nehring, 1889), coreanus (Heude, 1897), gigas (Heude, 1892), mandchuricus (Heude, 1897), songaricus (Heude, 1897) | |

| Banded pig S. s. vittatus |

_(8750051577).jpg.webp) |

Boie, 1828 | A small, short-faced and sparsely furred subspecies with a white band on the muzzle; it might be a separate species and shows some similarities with some other suid species in Southeast Asia.[20] | From Peninsular Malaysia, and in Indonesia from Sumatra and Java east to Komodo | andersoni (Thomas and Wroughton, 1909), jubatulus (Miller, 1906), milleri (Jentink, 1905), pallidiloris (Mees, 1957), peninsularis (Miller, 1906), rhionis (Miller, 1906), typicus (Heude, 1899) |

Domestication

With the exception of domestic pigs in Timor and Papua New Guinea (which appear to be of Sulawesi warty pig stock), the wild boar is the ancestor of most pig breeds.[18][26] Archaeological evidence suggests that pigs were domesticated from wild boar as early as 13,000–12,700 BCE in the Near East in the Tigris Basin,[27] being managed in the wild in a way similar to the way they are managed by some modern New Guineans.[28] Remains of pigs have been dated to earlier than 11,400 BCE in Cyprus. Those animals must have been introduced from the mainland, which suggests domestication in the adjacent mainland by then.[29] There was also a separate domestication in China, which took place about 8,000 years ago.[30][31]

DNA evidence from sub-fossil remains of teeth and jawbones of Neolithic pigs shows that the first domestic pigs in Europe had been brought from the Near East. This stimulated the domestication of local European wild boars, resulting in a third domestication event with the Near Eastern genes dying out in European pig stock. Modern domesticated pigs have involved complex exchanges, with European domesticated lines being exported in turn to the ancient Near East.[32][33] Historical records indicate that Asian pigs were introduced into Europe during the 18th and early 19th centuries.[30] Domestic pigs tend to have much more developed hindquarters than their wild boar ancestors, to the point where 70% of their body weight is concentrated in the posterior, which is the opposite of wild boar, where most of the muscles are concentrated on the head and shoulders.[34]

Synonymous species

The Heude's pig (Sus bucculentus), also known as the Indochinese warty pig or Vietnam warty pig, was an alleged pig species found in Laos and Vietnam. It was virtually unknown and was feared extinct, until the discovery of a skull from a recently killed individual in the Annamite Range, Laos, in 1995.[35] Recent evidence has suggested that the Heude's pig may be identical to (and consequently a synonym of) wild boars from Indochina east of the Mekong, and the American Society of Mammalogists now recognizes it as such.[5]

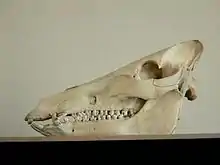

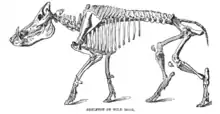

Description

The wild boar is a bulky, massively built suid with short and relatively thin legs. The trunk is short and robust, while the hindquarters are comparatively underdeveloped. The region behind the shoulder blades rises into a hump and the neck is short and thick to the point of being nearly immobile. The animal's head is very large, taking up to one-third of the body's entire length.[3] The structure of the head is well suited for digging. The head acts as a plough, while the powerful neck muscles allow the animal to upturn considerable amounts of soil:[36] it is capable of digging 8–10 cm (3.1–3.9 in) into frozen ground and can upturn rocks weighing 40–50 kg (88–110 lb).[10] The eyes are small and deep-set and the ears long and broad. The species has well developed canine teeth, which protrude from the mouths of adult males. The medial hooves are larger and more elongated than the lateral ones and are capable of quick movements.[3] The animal can run at a maximum speed of 40 km/h (25 mph) and jump at a height of 140–150 cm (55–59 in).[10]

Sexual dimorphism is very pronounced in the species, with males being typically 5–10% larger and 20–30% heavier than females. Males also sport a mane running down the back, which is particularly apparent during autumn and winter.[37] The canine teeth are also much more prominent in males and grow throughout life. The upper canines are relatively short and grow sideways early in life, though they gradually curve upwards. The lower canines are much sharper and longer, with the exposed parts measuring 10–12 cm (3.9–4.7 in) in length. In the breeding period, males develop a coating of subcutaneous tissue, which may be 2–3 cm (0.79–1.18 in) thick, extending from the shoulder blades to the rump, thus protecting vital organs during fights. Males sport a roughly egg-sized sack near the opening of the penis, which collects urine and emits a sharp odour. The function of this sack is not fully understood.[3]

Adult size and weight is largely determined by environmental factors; boars living in arid areas with little productivity tend to attain smaller sizes than their counterparts inhabiting areas with abundant food and water. In most of Europe, males average 75–100 kg (165–220 lb) in weight, 75–80 cm (30–31 in) in shoulder height and 150 cm (59 in) in body length, whereas females average 60–80 kg (130–180 lb) in weight, 70 cm (28 in) in shoulder height and 140 cm (55 in) in body length. In Europe's Mediterranean regions, males may reach average weights as low as 50 kg (110 lb) and females 45 kg (99 lb), with shoulder heights of 63–65 cm (25–26 in). In the more productive areas of Eastern Europe, males average 110–130 kg (240–290 lb) in weight, 95 cm (37 in) in shoulder height and 160 cm (63 in) in body length, while females weigh 95 kg (209 lb), reach 85–90 cm (33–35 in) in shoulder height, and reach 145 cm (57 in) in body length. In Western and Central Europe, the largest males weigh 200 kg (440 lb) and females 120 kg (260 lb). In Northeastern Asia, large males can reach brown bear-like sizes, weighing 270 kg (600 lb) and measuring 110–118 cm (43–46 in) in shoulder height. Some adult males in Ussuriland and Manchuria have been recorded to weigh 300–350 kg (660–770 lb) and measure 125 cm (49 in) in shoulder height. Adults of this size are generally immune from wolf predation.[38] Such giants are rare in modern times, due to past overhunting preventing animals from attaining their full growth.[3]

The winter coat consists of long, coarse bristles underlaid with short brown downy fur. The length of these bristles varies along the body, with the shortest being around the face and limbs and the longest running along the back. These back bristles form the aforementioned mane prominent in males and stand erect when the animal is agitated. Colour is highly variable; specimens around Lake Balkhash are very lightly coloured, and can even be white, while some boars from Belarus and Ussuriland can be black. Some subspecies sport a light-coloured patch running backward from the corners of the mouth. Coat colour also varies with age, with piglets having light brown or rusty-brown fur with pale bands extending from the flanks and back.[3]

The wild boar produces a number of different sounds which are divided into three categories:

- Contact calls: Grunting noises which differ in intensity according to the situation.[39] Adult males are usually silent, while females frequently grunt and piglets whine.[3] When feeding, boars express their contentment through purring. Studies have shown that piglets imitate the sounds of their mother, thus different litters may have unique vocalisations.[39]

- Alarm calls: Warning cries emitted in response to threats.[39] When frightened, boars make loud huffing ukh! ukh! sounds or emit screeches transcribed as gu-gu-gu.[3]

- Combat calls: High-pitched, piercing cries.[39]

Its sense of smell is very well developed to the point that the animal is used for drug detection in Germany.[40] Its hearing is also acute, though its eyesight is comparatively weak,[3] lacking color vision[40] and being unable to recognise a standing human 10–15 metres (33–49 ft) away.[10]

Pigs are one of four known mammalian taxa which possess mutations in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor that protect against snake venom. Mongooses, honey badgers, hedgehogs, and pigs all have modifications to the receptor pocket which prevents the snake venom α-neurotoxin from binding. These represent four separate, independent mutations.[41]

Social behaviour and life cycle

Boars are typically social animals, living in female-dominated sounders consisting of barren sows and mothers with young led by an old matriarch. Male boars leave their sounder at the age of 8–15 months, while females either remain with their mothers or establish new territories nearby. Subadult males may live in loosely knit groups, while adult and elderly males tend to be solitary outside the breeding season.[9][lower-alpha 1]

The breeding period in most areas lasts from November to January, though most mating only lasts a month and a half. Prior to mating, the males develop their subcutaneous armour in preparation for confronting rivals. The testicles double in size and the glands secrete a foamy yellowish liquid. Once ready to reproduce, males travel long distances in search of a sounder of sows, eating little on the way. Once a sounder has been located, the male drives off all young animals and persistently chases the sows. At this point, the male fiercely fights potential rivals.[3] A single male can mate with 5–10 sows.[10] By the end of the rut, males are often badly mauled and have lost 20% of their body weight,[3] with bite-induced injuries to the penis being common.[43] The gestation period varies according to the age of the expecting mother. For first-time breeders, it lasts 114–130 days, while it lasts 133–140 days in older sows. Farrowing occurs between March and May, with litter sizes depending on the age and nutrition of the mother. The average litter consists of 4–6 piglets, with the maximum being 10–12.[3][lower-alpha 2] The piglets are whelped in a nest constructed from twigs, grasses and leaves. Should the mother die prematurely, the piglets are adopted by the other sows in the sounder.[45]

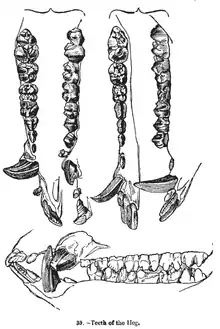

Newborn piglets weigh around 600–1,000 grams, lacking underfur and bearing a single milk incisor and canine on each half of the jaw.[3] There is intense competition between the piglets over the most milk-rich nipples, as the best-fed young grow faster and have stronger constitutions.[45] The piglets do not leave the lair for their first week of life. Should the mother be absent, the piglets lie closely pressed to each other. By two weeks of age, the piglets begin accompanying their mother on her journeys. Should danger be detected, the piglets take cover or stand immobile, relying on their camouflage to keep them hidden. The neonatal coat fades after three months, with adult colouration being attained at eight months. Although the lactation period lasts 2.5–3.5 months, the piglets begin displaying adult feeding behaviours at the age of 2–3 weeks. The permanent dentition is fully formed by 1–2 years. With the exception of the canines in males, the teeth stop growing during the middle of the fourth year. The canines in old males continue to grow throughout their lives, curving strongly as they age. Sows attain sexual maturity at the age of one year, with males attaining it a year later. However, estrus usually first occurs after two years in sows, while males begin participating in the rut after 4–5 years, as they are not permitted to mate by the older males.[3] The maximum lifespan in the wild is 10–14 years, though few specimens survive past 4–5 years.[46] Boars in captivity have lived for 20 years.[10]

Behaviour and ecology

Habitat and sheltering

The wild boar inhabits a diverse array of habitats from boreal taigas to deserts.[3] In mountainous regions, it can even occupy alpine zones, occurring up to 1,900 m (6,200 ft) in the Carpathians, 2,600 m (8,500 ft) in the Caucasus and up to 3,600–4,000 m (11,800–13,100 ft) in the mountains in Central Asia and Kazakhstan.[3] In order to survive in a given area, wild boars require a habitat fulfilling three conditions: heavily brushed areas providing shelter from predators, water for drinking and bathing purposes and an absence of regular snowfall.[47]

The main habitats favored by boars in Europe are deciduous and mixed forests, with the most favorable areas consisting of forest composed of oak and beech enclosing marshes and meadows. In the Białowieża Forest, the animal's primary habitat consists of well-developed broad-leaved and mixed forests, along with marshy mixed forests, with coniferous forests and undergrowths being of secondary importance. Forests made up entirely of oak groves and beeches are used only during the fruit-bearing season. This is in contrast to the Caucasian and Transcaucasian mountain areas, where boars will occupy such fruit-bearing forests year-round. In the mountainous areas of the Russian Far East, the species inhabits nutpine groves, hilly mixed forests where Mongolian oak and Korean pine are present, swampy mixed taiga and coastal oak forests. In Transbaikalia, boars are restricted to river valleys with nut pine and shrubs. Boars are regularly encountered in pistachio groves in winter in some areas of Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, while in spring they migrate to open deserts; boar have also colonized deserts in several areas they have been introduced to.[3][47][48]

On the islands of Komodo and Rinca, the boar mostly inhabits savanna or open monsoon forests, avoiding heavily forested areas unless pursued by humans.[11] Wild boar are known to be competent swimmers, capable of covering long distances. In 2013, one boar was reported to have completed the 11-kilometre (7 mi) swim from France to Alderney in the Channel Islands. Due to concerns about disease, it was shot and incinerated.[49]

Wild boar rest in shelters, which contain insulating material like spruce branches and dry hay. These resting places are occupied by whole families (though males lie separately) and are often located in the vicinity of streams, in swamp forests and in tall grass or shrub thickets. Boars never defecate in their shelters and will cover themselves with soil and pine needles when irritated by insects.[10]

Diet

.jpg.webp)

The wild boar is a highly versatile omnivore, whose diversity in choice of food is comparable to that of humans.[36] Their foods can be divided into four categories:

- Rhizomes, roots, tubers and bulbs, all of which are dug up throughout the year in the animal's whole range.[3]

- Nuts, berries and seeds, which are consumed when ripened and are dug up from the snow when necessary.[3]

- Leaves, bark, twigs and shoots, along with garbage.[3]

- Earthworms, insects, mollusks, fish, rodents, insectivores, bird eggs, lizards, snakes, frogs and carrion. Most of these prey items are taken in warm periods.[3]

A 50 kg (110 lb) boar needs around 4,000–4,500 calories of food per day, though this required amount increases during winter and pregnancy,[36] with the majority of its diet consisting of food items dug from the ground, like underground plant material and burrowing animals.[3] Acorns and beechnuts are invariably its most important food items in temperate zones,[50] as they are rich in the carbohydrates necessary for the buildup of fat reserves needed to survive lean periods.[36] In Western Europe, underground plant material favoured by boars includes bracken, willow herb, bulbs, meadow herb roots and bulbs and the bulbs of cultivated crops. Such food is favoured in early spring and summer, but may also be eaten in autumn and winter during beechnut and acorn crop failures. Should regular wild foods become scarce, boars will eat tree bark and fungi, as well as visit cultivated potato and artichoke fields.[3] Boar soil disturbance and foraging have been shown to facilitate invasive plants.[51][52] Boars of the vittatus subspecies in Ujung Kulon National Park in Java differ from most other populations by their primarily frugivorous diet, which consists of 50 different fruit species, especially figs, thus making them important seed dispersers.[4] The wild boar can consume numerous genera of poisonous plants without ill effect, including Aconitum, Anemone, Calla, Caltha, Ferula and Pteridium.[10]

Boars may occasionally prey on small vertebrates like newborn deer fawns, leporids and galliform chicks.[36] Boars inhabiting the Volga Delta and near some lakes and rivers of Kazakhstan have been recorded to feed extensively on fish like carp and Caspian roach. Boars in the former area will also feed on cormorant and heron chicks, bivalved molluscs, trapped muskrats and mice.[3] There is at least one record of a boar killing and eating a bonnet macaque in southern India's Bandipur National Park, though this may have been a case of intraguild predation, brought on by interspecific competition for human handouts.[53] There is also at least one recorded case of a group of wild boar attacking, killing, and eating an adult, healthy female axis deer (Axis axis) as a pack.[54]

Predators

Piglets are vulnerable to attack from medium-sized felids like Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), jungle cats (Felis chaus), and snow leopards (Panthera uncia), as well as other carnivorans like brown bears (Ursus arctos) and yellow-throated martens (Martes flavigula).[3]

The wolf (Canis lupus) is the main predator of wild boar throughout most of its range. A single wolf can kill around 50 to 80 boars of differing ages in one year.[3] In Italy[55] and Belarus' Belovezhskaya Pushcha National Park, boars are the wolf's primary prey, despite an abundance of alternative, less powerful ungulates.[55] Wolves are particularly threatening during the winter, when deep snow impedes the boars' movements. In the Baltic regions, heavy snowfall can allow wolves to eliminate boars from an area almost completely. Wolves primarily target piglets and subadults and only rarely attack adult sows. Adult males are usually avoided entirely.[3] Dholes (Cuon alpinus) may also prey on boars, to the point of keeping their numbers down in northwestern Bhutan, despite there being many more cattle in the area.[56]

Leopards (Panthera pardus) are predators of wild boar in the Caucasus (particularly Transcaucasia), the Russian Far East, India, China[57] and Iran. In most areas, boars constitute only a small part of the leopard's diet. However, in Iran's Sarigol National Park, boars are the second most frequently targeted prey species after mouflon (Ovis gmelini), though adult individuals are generally avoided, as they are above the leopard's preferred weight range of 10–40 kg (22–88 lb).[58] This dependence on wild boar is largely due in part to the local leopard subspecies' large size.[59]

Boars of all ages were once the primary prey of the tiger (Panthera tigris) in Transcaucasia, Kazakhstan, Middle Asia and the Far East up until the late 19th century. In modern times, tiger numbers are too low to have a limiting effect on boar populations. A single tiger can systematically destroy an entire sounder by preying on its members one by one, before moving on to another sounder. Tigers have been noted to chase boars for longer distances than with other prey. In two rare cases, boars were reported to gore a small tiger and a tigress to death in self-defense.[60] A "large male tiger" died of wounds inflicted by an old wild boar it had killed in "a battle royal" between the two animals.[61]: 500

In the Amur region, wild boars are one of the two most important prey species for Siberian tigers, alongside the Manchurian wapiti (Cervus canadensis xanthopygus), with the two species collectively comprising roughly 80% of the felid's prey.[62] In Sikhote Alin, a tiger can kill 30–34 boars a year.[10] Studies of tigers in India indicate that boars are usually secondary in preference to various cervids and bovids, though when boars are targeted, healthy adults are caught more frequently than young and sick specimens.[63]

On the islands of Komodo, Rinca and Flores, the boar's main predator is the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis).[11]

Distribution and habitat

Reconstructed range

The species originally occurred in North Africa and much of Eurasia; from the British Isles to Korea and the Sunda Islands. The northern limit of its range extended from southern Scandinavia to southern Siberia and Japan. Within this range, it was only absent in extremely dry deserts and alpine zones. It was once found in North Africa along the Nile valley up to Khartoum and north of the Sahara. The species occurs on a few Ionian and Aegean Islands, sometimes swimming between islands.[64] The reconstructed northern boundary of the animal's Asian range ran from Lake Ladoga (at 60°N) through the area of Novgorod and Moscow into the southern Urals, where it reached 52°N. From there, the boundary passed Ishim and farther east the Irtysh at 56°N. In the eastern Baraba steppe (near Novosibirsk) the boundary turned steep south, encircled the Altai Mountains and went again eastward including the Tannu-Ola Mountains and Lake Baikal. From here, the boundary went slightly north of the Amur River eastward to its lower reaches at the Sea of Okhotsk. On Sakhalin, there are only fossil reports of wild boar. The southern boundaries in Europe and Asia were almost invariably identical to the seashores of these continents. It is absent in the dry regions of Mongolia from 44 to 46°N southward, in China westward of Sichuan and in India north of the Himalayas. It is absent in the higher elevations of the Pamir and the Tian Shan, though they do occur in the Tarim basin and on the lower slopes of the Tien Shan.[3]

Present range

In recent centuries, the range of wild boar has changed dramatically, largely due to hunting by humans and more recently because of captive wild boar escaping into the wild. Prior to the 20th century, boar populations had declined in numerous areas, with British populations probably becoming extinct during the 13th century.[65] In the warm period after the ice age, wild boar lived in the southern parts of Sweden and Norway and north of Lake Ladoga in Karelia.[66] It was previously thought that the species did not live in Finland during prehistory because no prehistoric wild boar bones had been found within the borders of the country.[67][68] It was not until 2013, when a wild boar bone was found in Askola, that the species was found to have lived in Finland more than 8,000 years ago. It is believed, however, that man prevented its establishment by hunting.[69][70] In Denmark, the last boar was shot at the beginning of the 19th century, and by 1900 they were absent in Tunisia and Sudan and large areas of Germany, Austria and Italy. In Russia, they were extirpated in wide areas by the 1930s.[3] The last boar in Egypt reportedly died on 20 December 1912 in the Giza Zoo, with wild populations having disappeared by 1894–1902. Prince Kamal el Dine Hussein attempted to repopulate Wadi El Natrun with boars of Hungarian stock, but they were quickly exterminated by poachers.[71]

A revival of boar populations began in the middle of the 20th century. By 1950, wild boar had once again reached their original northern boundary in many parts of their Asiatic range. By 1960, they reached Leningrad and Moscow and by 1975, they were to be found in Archangelsk and Astrakhan. In the 1970s they again occurred in Denmark and Sweden, where captive animals escaped and now survive in the wild. In England, wild boar populations re-established themselves in the 1990s, after escaping from specialist farms that had imported European stock.[65]

Status in Great Britain

Wild boars were apparently already becoming rare by the 11th century; a 1087 forestry law enacted by William the Conqueror punished through blinding the unlawful killing of a boar. Charles I attempted to reintroduce the species into the New Forest, though this population was exterminated during the Civil War. Between their medieval extinction and the 1980s, when wild boar farming began, only a handful of captive wild boar, imported from the continent, were present in Britain. Occasional escapes of wild boar from wildlife parks have occurred as early as the 1970s, but since the early 1990s significant populations have re-established themselves after escapes from farms, the number of which has increased as the demand for meat from the species has grown. A 1998 MAFF (now DEFRA) study on wild boar living wild in Britain confirmed the presence of two populations of wild boar living in Britain; one in Kent/East Sussex and another in Dorset.[65]

Another DEFRA report, in February 2008,[72] confirmed the existence of these two sites as 'established breeding areas' and identified a third in Gloucestershire/Herefordshire; in the Forest of Dean/Ross on Wye area. A 'new breeding population' was also identified in Devon. There is another significant population in Dumfries and Galloway. Populations estimates were as follows:

- The largest population, in Kent/East Sussex, was then estimated at 200 animals in the core distribution area.

- The smallest, in west Dorset, was estimated to be fewer than 50 animals.

- Since winter 2005–2006 significant escapes/releases have also resulted in animals colonizing areas around the fringes of Dartmoor, in Devon. These are considered as an additional single 'new breeding population' and currently estimated to be up to 100 animals.

Population estimates for the Forest of Dean are disputed as, at the time that the DEFRA population estimate was 100, a photo of a boar sounder in the forest near Staunton with over 33 animals visible was published and at about the same time over 30 boar were seen in a field near the original escape location of Weston under Penyard many kilometres or miles away. In early 2010 the Forestry Commission embarked on a cull,[73] with the aim of reducing the boar population from an estimated 150 animals to 100. By August it was stated that efforts were being made to reduce the population from 200 to 90, but that only 25 had been killed.[74] The failure to meet cull targets was confirmed in February 2011.[75]

Wild boars have crossed the River Wye into Monmouthshire, Wales. Iolo Williams, the BBC Wales wildlife expert, attempted to film Welsh boar in late 2012.[76] Many other sightings, across the UK, have also been reported.[77] The effects of wild boar on the U.K.'s woodlands were discussed with Ralph Harmer of the Forestry Commission on the BBC Radio's Farming Today radio programme in 2011. The programme prompted activist writer George Monbiot to propose a thorough population study, followed by the introduction of permit-controlled culling.[78]

Introduction to North America

Wild boars are an invasive species in the Americas and cause problems including out-competing native species for food, destroying the nests of ground-nesting species, killing fawns and young domestic livestock, destroying agricultural crops, eating tree seeds and seedlings, destroying native vegetation and wetlands through wallowing, damaging water quality, coming into violent conflict with humans and pets and carrying pig and human diseases including brucellosis, trichinosis and pseudorabies. In some jurisdictions, it is illegal to import, breed, release, possess, sell, distribute, trade, transport, hunt, or trap Eurasian boars. Hunting and trapping is done systematically, to increase the chance of eradication and to remove the incentive to illegally release boars, which have mostly been spread deliberately by sport hunters.[79]

History

While domestic pigs, both captive and feral (popularly termed "razorbacks"), have been in North America since the earliest days of European colonization, pure wild boars were not introduced into the New World until the 19th century. The suids were released into the wild by wealthy landowners as big game animals. The initial introductions took place in fenced enclosures, though several escapes occurred, with the escapees sometimes intermixing with already established feral pig populations.

The first of these introductions occurred in New Hampshire in 1890. Thirteen wild boars from Germany were purchased by Austin Corbin from Carl Hagenbeck and released into a 9,500-hectare (23,000-acre) game preserve in Sullivan County. Several of these boars escaped, though they were quickly hunted down by locals. Two further introductions were made from the original stocking, with several escapes taking place due to breaches in the game preserve's fencing. These escapees have ranged widely, with some specimens having been observed crossing into Vermont.[80]

In 1902, 15–20 wild boar from Germany were released into a 3,200-hectare (7,900-acre) estate in Hamilton County, New York. Several specimens escaped six years later, dispersing into the William C. Whitney Wilderness Area, with their descendants surviving for at least 20 years.[80]

The most extensive boar introduction in the US took place in western North Carolina in 1912, when 13 boars of undetermined European origin were released into two fenced enclosures in a game preserve in Hooper Bald, Graham County. Most of the specimens remained in the preserve for the next decade, until a large-scale hunt caused the remaining animals to break through their confines and escape. Some of the boars migrated to Tennessee, where they intermixed with both free-ranging and feral pigs in the area. In 1924, a dozen Hooper Bald wild pigs were shipped to California and released in a property between Carmel Valley and the Los Padres National Forest. These hybrid boar were later used as breeding stock on various private and public lands throughout the state, as well as in other states like Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, West Virginia and Mississippi.[80]

Several wild boars from Leon Springs and the San Antonio, Saint Louis and San Diego Zoos were released in the Powder Horn Ranch in Calhoun County, Texas, in 1939. These specimens escaped and established themselves in surrounding ranchlands and coastal areas, with some crossing the Espiritu Santo Bay and colonizing Matagorda Island. Descendants of the Powder Horn Ranch boars were later released onto San José Island and the coast of Chalmette, Louisiana.[80]

Wild boar of unknown origin were stocked in a ranch in the Edwards Plateau in the 1940s, only to escape during a storm and hybridize with local feral pig populations, later spreading into neighboring counties.[80]

Starting in the mid-1980s, several boars purchased from the San Diego Zoo and Tierpark Berlin were released into the United States. A decade later, more specimens from farms in Canada and Białowieża Forest were let loose. In recent years, wild pig populations have been reported in 44 states within the US, most of which are likely wild boar–feral hog hybrids. Pure wild boar populations may still be present, but are extremely localized.[80]

Introduction and lack of control in South America

In South America, the European boar is believed to have been introduced for the first time in Argentina and Uruguay around the 20th century for breeding purposes.[81] In Brazil, the creation of wild boar and hybrids started on a large scale in the mid-1990s. With the invasion of wild boar that crossed the border and entered Rio Grande do Sul around 1989, and the escape and intentional release by several Brazilian breeders in the late 1990s – in response to a IBAMA decision against the import and breeding of wild boar in 1998 – numerous feral species formed a growing population, which progressively advances in Brazilian territory.[82][83] The species has no natural predators in Brazil, as it is an exotic species, in addition to breeding with the domestic pig, generating the so-called "javaporco" (neologism created to define this hybrid), factors that contribute to the exaggerated increase in the population.[82] With its population in continuous and uncontrolled growth, without predators, the wild boar causes environmental damage, contributing to the aggradation of river and stream springs, attacking native species feeding on eggs and puppies, causing damage to fauna, flora and to agriculture and livestock, since it also attacks farm animals and can carry various diseases, including zoonosis.

Pest control in Brazil

As a form of control for the wild boar population (which is considered a pest and harmful species), hunting and killing are allowed for Collectors, Shooters and Hunters (CACs)[84] duly registered by the environmental control agency, IBAMA, which, on the other hand, seeks to encourage the preservation of similar species of native peccaries, such as the "queixada" and the "caititu".[85][86][87]

Effect on other habitats

Wild boars negatively impact other habitats through the destruction of the environment, or homes of wildlife. When wild boars invade new areas, they adapt to the new area by trampling and rooting, as well as displacing many saplings/nutrients. This causes a decrease in growing of many plants and trees. Water is also affected negatively by wild boars. When wild boars are active in streams, or small pools of water, it causes increased turbidity (excessive silt and particle suspension).[88] In some cases, the fecal coliform concentration increases to dangerous levels because of wild boars. Aquatic wildlife is affected, more prominently fish, and amphibians. Wild boars have caused a great decrease in over 300 animal or plant species, 250 being endangered or threatened.[89]

The boars cause many habitats to become less diverse because of their feeding behaviors and predation. Wild boars will dig up eggs of species and eat them, as well as killing other wildlife for food. When these boars compete with other species for resources, they usually come out successful.[90] A study published in the Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology was conducted on the results of Feral Swine control. Only two years after the control started, the amount of turtle nests jumped from 57 to 143, and the turtle nest predation percent dropped from 74 to 15.[91] They kill and eat deers, lizards, birds, snakes, and more. These boars are called "opportunist omnivores," which means they eat almost anything. This means they can survive almost anywhere. A big surplus of food and the ability to adapt to any new place causes lots of breeding. All of these factors make it difficult to get rid of wild boars.[92] Wild boars also tend to carry diseases and numerous pathogens. This also adds to the decrease in diversity among species.

Diseases and parasites

Wild boars are known to host at least 20 different parasitic worm species, with maximum infections occurring in summer. Young animals are vulnerable to helminths like Metastrongylus, which are consumed by boars through earthworms and cause death by parasitising the lungs. Wild boar also carry parasites known to infect humans, including Gastrodiscoides, Trichinella spiralis, Taenia solium, Balantidium coli and Toxoplasma gondii.[93] Wild boar in southern regions are frequently infested with ticks (Dermacentor, Rhipicephalus, and Hyalomma) and hog lice. The species also suffers from blood-sucking flies, which it escapes by bathing frequently or hiding in dense shrubs.[3]

Swine plague spreads very quickly in wild boar, with epizootics being recorded in Germany, Poland, Hungary, Belarus, the Caucasus, the Far East, Kazakhstan and other regions. Foot-and-mouth disease can also take on epidemic proportions in boar populations. The species occasionally, but rarely contracts Pasteurellosis, hemorrhagic sepsis, tularemia, and anthrax. Wild boar may on occasion contract swine erysipelas through rodents or hog lice and ticks.[3]

Relationships with humans

In culture

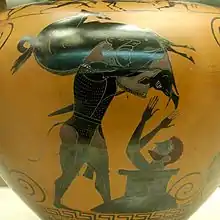

The wild boar features prominently in the cultures of Indo-European people, many of which saw the animal as embodying warrior virtues.[97] Cultures throughout Europe and Asia Minor saw the killing of a boar as proof of one's valor and strength. Neolithic hunter gatherers depicted reliefs of ferocious wild boars on their temple pillars at Göbekli Tepe some 11,600 years ago.[98][99] Virtually all heroes in Greek mythology fight or kill a boar at one point. The demigod Herakles' third labour involves the capture of the Erymanthian Boar, Theseus slays the wild sow Phaea, and a disguised Odysseus is recognised by his handmaiden Eurycleia by the scars inflicted on him by a boar during a hunt in his youth.[100] To the mythical Hyperboreans, the boar represented spiritual authority.[94] Several Greek myths use the boar as a symbol of darkness, death and winter.[101] One example is the story of the youthful Adonis, who is killed by a boar and is permitted by Zeus to depart from Hades only during the spring and summer period. This theme also occurs in Irish and Egyptian mythology, where the animal is explicitly linked to the month of October, therefore autumn. This association likely arose from aspects of the boar's actual nature. Its dark colour was linked to the night, while its solitary habits, proclivity to consume crops and nocturnal nature were associated with evil.[102] The foundation myth of Ephesus has the city being built over the site where Prince Androklos of Athens killed a boar.[103] Boars were frequently depicted on Greek funerary monuments alongside lions, representing gallant losers who have finally met their match, as opposed to victorious hunters as lions are. The theme of the doomed, yet valorous boar warrior also occurred in Hittite culture, where it was traditional to sacrifice a boar alongside a dog and a prisoner of war after a military defeat.[100]

The boar as a warrior also appears in Germanic cultures, with its image having been frequently engraved on shields and swords. They also feature on Germanic boar helmets, such as the Benty Grange helmet, where it was believed to offer protection to the wearer and has been theorised to have been used in spiritual transformations into swine, similar to berserkers. The boar features heavily in religious practice in Germanic paganism where it is closely associated with Freyr and has also been suggested to have been a totemic animal to the Swedes, especially to the Yngling royal dynasty who claimed descent from the god.[104]

According to Tacitus, the Baltic Aesti featured boars on their helmets and may have also worn boar masks. The boar and pig were held in particularly high esteem by the Celts, who considered them to be their most important sacred animal. Some Celtic deities linked to boars include Moccus and Veteris. It has been suggested that some early myths surrounding the Welsh hero Culhwch involved the character being the son of a boar god.[100] Nevertheless, the importance of the boar as a culinary item among Celtic tribes may have been exaggerated in popular culture by the Asterix series, as wild boar bones are rare among Celtic archaeological sites and the few that do occur show no signs of butchery, having probably been used in sacrificial rituals.[105]

The boar also appears in Vedic mythology and Hindu mythology. A story present in the Brahmanas has the god Indra slaying an avaricious boar, who has stolen the treasure of the asuras, then giving its carcass to the god Vishnu, who offered it as a sacrifice to the gods. In the story's retelling in the Charaka Samhita, the boar is described as a form of Prajapati and is credited with having raised the Earth from the primeval waters. In the Ramayana and the Puranas, the same boar is portrayed as Varaha, an avatar of Vishnu.[106]

In Japanese culture, the boar is widely seen as a fearsome and reckless animal, to the point that several words and expressions in Japanese referring to recklessness include references to boars. The boar is the last animal of the Oriental zodiac, with people born during the year of the Pig being said to embody the boar-like traits of determination and impetuosity. Among Japanese hunters, the boar's courage and defiance is a source of admiration and it is not uncommon for hunters and mountain people to name their sons after the animal inoshishi (猪). Boars are also seen as symbols of fertility and prosperity; in some regions, it is thought that boars are drawn to fields owned by families including pregnant women, and hunters with pregnant wives are thought to have greater chances of success when boar hunting. The animal's link to prosperity was illustrated by its inclusion on the ¥10 note during the Meiji period and it was once believed that a man could become wealthy by keeping a clump of boar hair in his wallet.[107]

In the folklore of the Mongol Altai Uriankhai tribe, the wild boar was associated with the watery underworld, as it was thought that the spirits of the dead entered the animal's head, to be ultimately transported to the water.[108] Prior to the conversion to Islam, the Kyrgyz people believed that they were descended from boars and thus did not eat pork. In Buryat mythology, the forefathers of the Buryats descended from heaven and were nourished by a boar.[109] In China, the boar is the emblem of the Miao people.[94]

The boar (sanglier) is frequently displayed in English, Scottish and Welsh heraldry. As with the lion, the boar is often shown as armed and langued. As with the bear, Scottish and Welsh heraldry displays the boar's head with the neck cropped, unlike the English version, which retains the neck.[110] The white boar served as the badge of King Richard III of England, who distributed it among his northern retainers during his tenure as Duke of Gloucester.[111]

As a game animal and food source

Humans have been hunting boar for millennia, the earliest artistic depictions of such activities dating back to the Upper Paleolithic.[100] The animal was seen as a source of food among the Ancient Greeks, as well as a sporting challenge and source of epic narratives. The Romans inherited this tradition, with one of its first practitioners being Scipio Aemilianus. Boar hunting became particularly popular among the young nobility during the 3rd century BC as preparation for manhood and battle. A typical Roman boar hunting tactic involved surrounding a given area with large nets, then flushing the boar with dogs and immobilizing it with smaller nets. The animal would then be dispatched with a venabulum, a short spear with a crossguard at the base of the blade. More than their Greek predecessors, the Romans extensively took inspiration from boar hunting in their art and sculpture. With the ascension of Constantine the Great, boar hunting took on Christian allegorical themes, with the animal being portrayed as a "black beast" analogous to the dragon of Saint George.[112]

Boar hunting continued after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, though the Germanic tribes considered the red deer to be a more noble and worthy quarry. The post-Roman nobility hunted boar as their predecessors did, but primarily as training for battle rather than sport. It was not uncommon for medieval hunters to deliberately hunt boars during the breeding season when the animals were more aggressive. During the Renaissance, when deforestation and the introduction of firearms reduced boar numbers, boar hunting became the sole prerogative of the nobility, one of many charges brought up against the rich during the German Peasants' War and the French Revolution.[112]

During the mid-20th century, 7,000–8,000 boars were caught in the Caucasus, 6,000–7,000 in Kazakhstan and about 5,000 in Central Asia during the Soviet period, primarily through the use of dogs and beats.[3] In Nepal, farmers and poachers eliminate boars by baiting balls of wheat flour containing explosives with kerosene oil, with the animals' chewing motions triggering the devices.[113]

Wild boar can thrive in captivity, though piglets grow slowly and poorly without their mothers. Products derived from wild boar include meat, hide and bristles.[3] Apicius devotes a whole chapter to the cooking of boar meat, providing 10 recipes involving roasting, boiling and what sauces to use. The Romans usually served boar meat with garum.[114] Boar's head was the centrepiece of most medieval Christmas celebrations among the nobility.[115] Although growing in popularity as a captive-bred source of food, the wild boar takes longer to mature than most domestic pigs and it is usually smaller and produces less meat. Nevertheless, wild boar meat is leaner and healthier than pork,[116] being of higher nutritional value and having a much higher concentration of essential amino acids.[117] Most meat-dressing organizations agree that a boar carcass should yield 50 kg (110 lb) of meat on average. Large specimens can yield 15–20 kg (33–44 lb) of fat, with some giants yielding 30 kg (66 lb) or more. A boar hide can measure 300 dm2 (4,700 sq in) and can yield 350–1,000 grams (12–35 oz) of bristle and 400 grams (14 oz) of underwool.[3]

Roman relief of a dog confronting a boar, Cologne

Roman relief of a dog confronting a boar, Cologne Southern Indian depiction of boar hunt, c. 1540

Southern Indian depiction of boar hunt, c. 1540_A._E._Wardrop_I.png.webp) Pig-sticking in British India

Pig-sticking in British India.jpg.webp) Boar shot in Volgograd Oblast, Russia

Boar shot in Volgograd Oblast, Russia The Boar Hunt – Hans Wertinger, c. 1530, the Danube Valley

The Boar Hunt – Hans Wertinger, c. 1530, the Danube Valley

Crop and garbage raiding

Boars can be damaging to agriculture in situations where their natural habitat is sparse. Populations living on the outskirts of towns or farms can dig up potatoes and damage melons, watermelons and maize. However, they generally only encroach upon farms when natural food is scarce. In the Belovezh forest for example, 34–47% of the local boar population will enter fields in years of moderate availability of natural foods. While the role of boars in damaging crops is often exaggerated,[3] cases are known of boar depredations causing famines, as was the case in Hachinohe, Japan in 1749, where 3,000 people died of what became known as the "wild boar famine". Still, within Japanese culture, the boar's status as vermin is expressed through its title as "king of pests" and the popular saying (addressed to young men in rural areas) "When you get married, choose a place with no wild boar."[107][118]

In Central Europe, farmers typically repel boars through distraction or fright, while in Kazakhstan it is usual to employ guard dogs in plantations. However, research shows that when compared with other mitigation tactics, hunting is the only strategy to significantly reduce crop damage by boars.[119] Although large boar populations can play an important role in limiting forest growth, they are also useful in keeping pest populations such as June bugs under control.[3] The growth of urban areas and the corresponding decline in natural boar habitats has led to some sounders entering human habitations in search of food. As in natural conditions, sounders in peri-urban areas are matriarchal, though males tend to be much less represented and adults of both sexes can be up to 35% heavier than their forest-dwelling counterparts. As of 2010, at least 44 cities in 15 countries have experienced problems of some kind relating to the presence of habituated wild boar.[120]

Attacks on humans

Actual attacks on humans are rare, but can be serious, resulting in penetrating injuries to the lower part of the body. They generally occur during the boars' rutting season from November to January, in agricultural areas bordering forests or on paths leading through forests. The animal typically attacks by charging and pointing its tusks towards the intended victim, with most injuries occurring on the thigh region. Once the initial attack is over, the boar steps back, takes position and attacks again if the victim is still moving, only ending once the victim is completely incapacitated.[121][122]

Boar attacks on humans have been documented throughout history. The Romans and Ancient Greeks wrote of these attacks (Odysseus was wounded by a boar and Adonis was killed by one). A 2012 study compiling recorded attacks from 1825 to 2012 found accounts of 665 human victims of both wild boars and feral pigs, with the majority (19%) of attacks in the animal's native range occurring in India. Most of the attacks occurred in rural areas during the winter months in non-hunting contexts and were committed by solitary males.[123]

Management

Managing wild boar is a pressing task in both native and invasive contexts as they can be disrupting to other systems when not addressed. Wild boar find their success through adaptation of daily patterns to circumvent threats. They avoid human contact through nocturnal lifestyles, despite the fact that they are not evolutionarily predisposed, and alter their diets substantially based on what is available.[124] These "adaptive generalists", can survive in a variety of landscapes, making the prediction of their movement patterns and any potential close contact areas crucial to limiting damage.[125] All of these qualities make them equally difficult to manage or limit.

Within Central Europe, the native habitat of the wild boar, there has been a push to re-evaluate interactions between wild boar and humans, with the priority of fostering positive engagement. Negative media and public perception of wild boar as "crop raiders" have made those living alongside them less willing to accept the economic damages of their behaviors, as wild boar are seen as pests. This media tone impacts management policy, with every 10 negative articles increasing wild boar policy activity by 6.7%.[126] Contrary to this portrayal, wild boar, when managed well within their natural environments, can be a crucial part of forest ecosystems.

Defining the limits of proper management is difficult, but the exclusion of wild boar from rare environments is generally agreed upon, as when not properly managed, they can damage agricultural ventures and harm vulnerable plant life.[127] These damages are estimated at $800 million yearly in environmental and financial costs for the United States alone.[127] The breadth of this damage is due to prior inattention and lack of management tactics for extended lengths of time.[126] Managing wild boar is a complex task, as it involves coordinating a combination of crop harvest techniques, fencing, toxic bait, corrals, and hunting. The most common tactic employed by private land owners in the United States is recreational hunting, however, this is generally not as effective on its own.[128] Management strategies are most successful when they take into account reproduction, dispersion, and the differences between ideal resources for males and females.[125]

See also

- Babirusa

- Boar-baiting

- Domestic pig

- Feral pig

- Peccary

- Indian boar

- Boars in heraldry

Notes

- It is from the male boar's solitary habits that the species gets its name in numerous Romance languages. Although the Latin word for "boar" was aper, the French sanglier and Italian cinghiale derive from singularis porcus, which is Latin for "solitary pig".[42]

- Thirteen has been observed in a captive specimen.[44]

References

- Keuling, O.; Leus, K. (2019). "Sus scrofa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T41775A44141833. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T41775A44141833.en. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Heptner, V. G.; Nasimovich, A. A.; Bannikov, A. G.; Hoffman, R. S. (1988). Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union]. Vol. I. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation. pp. 19–82.

- Oliver, W. L. R.; et al. (1993). "The Common Wild Pig (Sus scrofa)". In Oliver, W. L. R. (ed.). Pigs, Peccaries, and Hippos – 1993 Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN / SSC Pigs and Peccaries Specialist Group. pp. 112–121. ISBN 2-8317-0141-4.

- "Explore the Database". mammaldiversity.org. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- "Boar – mammal". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- Chen, K.; et al. (2007). "Genetic Resources, Genome Mapping and Evolutionary Genomics of the Pig (Sus scrofa)". Int J Biol Sci. 3 (3): 153–165. doi:10.7150/ijbs.3.153. PMC 1802013. PMID 17384734.

- Kurtén, Björn (1968). Pleistocene mammals of Europe. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 153–155

- Marsan & Mattioli 2013, pp. 75–76

- Baskin, L.; Danell, K. (2003). Ecology of Ungulates: A Handbook of Species in North, Central, and South America, Eastern Europe and Northern and Central Asia. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 15–38. ISBN 3-540-43804-1.

- Affenberg, W. (1981). The Behavioral Ecology of the Komodo Monitor. University Press of Florida. p. 248. ISBN 0-8130-0621-X.

- "Online Etymological Dictionary". Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- Magnier, Eileen (7 May 2020). "Wild boarlets born in Donegal believed to be first in 800 years". RTE. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- "Latin Dictionary and Grammar Resources". Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- Cabanau 2001, pp. 24

- Ruvinsky, A. et al. (2011). "Systematics and evolution of the pig". In: Ruvinsky A, Rothschild MF (eds), The Genetics of the Pig. 2nd ed. CAB International, Oxon. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-1-84593-756-0

- Groves, C. P. et al. 1993. The Eurasian Suids Sus and Babyrousa. In Oliver, W. L. R., ed., Pigs, Peccaries, and Hippos – 1993 Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, 107–108. IUCN/SSC Pigs and Peccaries Specialist Group, ISBN 2-8317-0141-4

- Hemmer, H. (1990), Domestication: The Decline of Environmental Appreciation, Cambridge University Press, pp. 55–59, ISBN 0-521-34178-7

- Kingdon, J. (1997). The Kingdon Guide to African Mammals. p. 329. Academic Press Limited. ISBN 0-12-408355-2

- Groves, C. (2008). Current views on the taxonomy and zoogeography of the genus Sus. pp. 15–29 in Albarella, U., Dobney, K, Ervynck, A. & Rowley-Conwy, P. Eds. (2008). Pigs and Humans: 10,000 Years of Interaction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920704-6

- Sterndale, R. A. (1884), Natural history of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon, Calcutta : Thacker, Spink, pp. 415–420

- Scheggi 1999, pp. 86–89

- Marsan & Mattioli 2013, pp. 14–15

- Wild Pig Specialist group. "LC – Eurasian Wild Pig". Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Clutton-Brock, J. (1999), A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals, Cambridge University Press, pp. 91–99, ISBN 0-521-63495-4

- The related collared peccary (Pecari tajacu) has been domesticated in the New World. "Commercial Farming of Collared Peccary: A Large-scale Commercial Farming of Collared Peccary (Tayassu tajacu) in North-eastern Brazil", 2007-4-30.

- Nelson, Sarah M. (1998). Ancestors for the Pigs: Pigs in prehistory. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. ISBN 9781931707091.

- Rosenberg M, Nesbitt R, Redding RW, Peasnall BL (1998). Hallan Çemi, pig husbandry, and post-Pleistocene adaptations along the Taurus-Zagros Arc (Turkey). Paléorient, 24(1):25–41.

- Vigne, JD; Zazzo, A; Saliège, JF; Poplin, F; Guilaine, J; Simmons, A (2009). "Pre-Neolithic wild boar management and introduction to Cyprus more than 11,400 years ago". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (38): 16135–8. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616135V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0905015106. PMC 2752532. PMID 19706455.

- Giuffra, E; Kijas, JM; Amarger, V; Carlborg, O; Jeon, JT; Andersson, L (2000). "The origin of the domestic pig: independent domestication and subsequent introgression". Genetics. 154 (4): 1785–91. doi:10.1093/genetics/154.4.1785. PMC 1461048. PMID 10747069.

- Jean-Denis Vigne; Anne Tresset & Jean-Pierre Digard (3 July 2012). History of domestication (PDF) (Speech).

- BBC News, "Pig DNA reveals farming history" 4 September 2007. The report concerns an article in the journal PNAS

- Larson, G; Albarella, U; Dobney, K; Rowley-Conwy, P; Schibler, J; Tresset, A; Vigne, JD; Edwards, CJ; et al. (2007). "Ancient DNA, pig domestication, and the spread of the Neolithic into Europe" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (39): 15276–81. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10415276L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703411104. PMC 1976408. PMID 17855556.

- Scheggi 1999, pp. 87

- Groves, C.P; Schaller, G.B.; Amato, G.; Khounboline, K. (March 1997). "Rediscovery of the wild pig Sus bucculentus". Nature. 386 (6623): 335. Bibcode:1997Natur.386..335G. doi:10.1038/386335a0. S2CID 4264868.

- Marsan & Mattioli 2013, pp. 70–72

- Marsan & Mattioli 2013, pp. 26

- Marsan & Mattioli 2013, pp. 28

- Cabanau 2001, pp. 29

- Cabanau 2001, pp. 28

- Drabeck, D.H.; Dean, A.M.; Jansa, S.A. (1 June 2015). "Why the honey badger don't care: Convergent evolution of venom-targeted nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mammals that survive venomous snake bites". Toxicon. 99: 68–72. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.03.007. PMID 25796346.

- Scheggi 1999, pp. 20–22

- Weiler, Ulrike; et al. (2016). "Penile Injuries in Wild and Domestic Pigs". Animals. 6 (4): 25. doi:10.3390/ani6040025. PMC 4846825. PMID 27023619.

- "Eight little piggies went a-marching". Whipsnade Zoo. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- Marsan & Mattioli 2013, pp. 83–86

- Marsan & Mattioli 2013, pp. 87–90

- Marsan & Mattioli 2013, pp. 55–58

- Long, J. L. (2003), Introduced Mammals of the World: Their History, Distribution and Influence, Cabi Publishing, ISBN 978-0-85199-748-3

- "Alderney wild boar that swam from France shot over disease fear". BBC News. 14 November 2013.

- FAO Ch.8

- Tierney, Trisha A.; Cushman, J. Hall (12 May 2006). "Temporal Changes in Native and Exotic Vegetation and Soil Characteristics following Disturbances by Feral Pigs in a California Grassland". Biological Invasions. 8 (5): 1073–1089. doi:10.1007/s10530-005-6829-7. S2CID 25706582.

- Oldfield, Callie A.; Evans, Jonathan P. (1 March 2016). "Twelve years of repeated wild hog activity promotes population maintenance of an invasive clonal plant in a coastal dune ecosystem". Ecology and Evolution. 6 (8): 2569–2578. doi:10.1002/ece3.2045. PMC 4834338. PMID 27110354.

- Gupta, S. et al. A wild boar hunting: predation on a bonnet macaque by a wild boar in the Bandipur National Park, southern India. Current Science. Vol. 106, No. 9. (10 May 2014)

- Behera, Satyaranian; Gupta, Rajendra Prasad (2007). "Predation on chital Axis axis by wild pig Sus scrofa in Bandhavgarh National Park". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 104 (3): 345–346.

- Marsan & Mattioli 2013, pp. 96–97

- Thinley, P; Kamler, JF; Wang, SW; Lham, K; Stenkewitz, U; et al. (2011). "Seasonal diet of dholes (Cuon alpinus) in northwestern Bhutan". Mammalian Biology. 76 (4): 518–520. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2011.02.003.

- Heptner, V. G. & Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Leopard". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 248–252.

- Taghdisi, M.; et al. (2013). "Diet and habitat use of the endangered Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in northeastern Iran". Turkish Journal of Zoology. 37: 554–561. doi:10.3906/zoo-1301-20.

- Sharbafi, Elmira; Farhadinia, Mohammad S.; Rezaie, Hamid R.; Braczkowski, Alex Richard (2016). "Prey of the Persian Leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in a mixed forest-steppe landscape in northeastern Iran (Mammalia: Felidae)". Zoology in the Middle East. 62 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/09397140.2016.1144286. S2CID 88354782.

- Heptner, V. G. & Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Tiger". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 174–185.

- Prynn, David (1980). "Tigers and Leopards in Russia's Far East". Oryx. Fauna & Flora International (CUP). 15 (5): 496–503. doi:10.1017/s0030605300029227. ISSN 0030-6053. S2CID 86199390.

- Miquelle, Dale G.; et al. (1996). "Food habits of Amur tigers in the Sikhote-Alin Zapovednik and the Russian Far East, and implications for conservation" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Research. 1 (2): 138. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2012.

- Schaller, G (1967). The deer and the tiger: a study of wildlife in India. p. 321. ISBN 9780226736570.

- Masseti, M. (2012), Atlas of terrestrial mammals of the Ionian and Aegean islands, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 139–141, ISBN 3-11-025458-1

- "Wild boar in Britain". Britishwildboar.org.uk. 21 October 1998. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- Nummi, Petri (1988). Suomeen istutetut riistaeläimet. Helsingin yliopisto, Maatalous- ja Metsäeläintieteen Laitos. pp. 37–38. ISBN 951-45-4760-8.

- Jääkauden jälkeläiset – Suomen nisäkkäiden varhainen historia Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish)

- Koivisto, M. (2004). Jääkaudet. WSOY. pp. 207–208. ISBN 951-0-29101-3.

- Tiedon jyvät – Villisika eli Suomessa jo kivikaudella. Helsingin Sanomat, 2014-12-05, p. B15.

- "Villisika eli Suomessa jo kivikaudella" (in Finnish). Suomen Luonto 4/2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Osborn, D.J.; Helmy, I. (1980). "Sus scrofa Linnaeus, 1758". The contemporary land mammals of Egypt (including Sinai). Field Museum of Natural History. pp. 475–477.

- Government supports local communities to manage wild boar. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 19 February 2008

- "Wild boar cull is given go ahead". BBC News. 2010.

- "Forest of Dean rangers battle to meet boar cull target". BBC News. 20 August 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- Cull failing to control wild boar. The Forester. 25 February 2011.

- "BBC Wales – Nature – Wildlife – Wild boar". BBC. 1970. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- "Wild Boar in Britain". Britishwildboar.org.uk. 31 December 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- Monbiot, George (16 September 2011). "How the UK's zoophobic legacy turned on wild boar". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

I was prompted to write this article by an item I heard on the BBC's Farming Today programme at the beginning of the week. It was an interview with Ralph Harmer, who works for the Forestry Commission, about whether or not the returning boars are damaging our woodlands. I was struck by what the item did not say. Not once did the programme mention that this is a native species. The boar was discussed as if it were an exotic invasive animal, such as the mink or the grey squirrel. […] Then, once we've found out how many boars, […] should be culled to allow a gentle expansion but not an explosion, permits to shoot them should be sold, and the money used to compensate farmers whose crops the boar have damaged. Other hunting should be banned. This is how they do it in France.

- "Eurasian Boar – NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation". dec.ny.gov.

- Mayer, J. J. et al. (2009), Wild Pigs: Biology, Damage, Control Techniques and Management Archived 24 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Savannah River National Laboratory Aiken, South Carolina, SRNL-RP-2009-00869

- Vininha F. Carvalho (19 January 2007). "As espécies invasoras representam um perigo á biodiversidade". animalivre.uol.com.br. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Felipe Pedrosaa, Rafael Salernob, Fabio Vinicius Borges Padilhac and Mauro Galetti (13 March 2015). "Current distribution of invasive feral pigs in Brazil: economic impacts and ecological uncertainty". naturezaeconservacao.com.br. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Carlos H. Salvador (3 July 2012). "Ecology and management of Eurasian wild boar (Sus scrofa L.) in South America". Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Murilo Souza and Cláudia Lemos (22 March 2021). "Projeto regulamenta a caça esportiva de animais no Brasil". Chamber of Deputies. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Débora Spitzcovsky (4 February 2013). "Brasil autoriza caça de javali-europeu em seu território". planetasustentavel.abril.com.br. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Fernanda Testa (13 September 2015). "Ameaça às lavouras, javalis são alvo de caça autorizada no interior de SP". g1.globo.com. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Bruna de Alencar, Vinicius Galera e Venilson Ferreira (10 February 2016). "Aberta a temporada de caça ao javali no Sul e Sudeste". revistagloborural.globo.com. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- State, Mississippi (11 November 2021). "Environmental Damage". Mississippi State University.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "FERAL SWINE: Impacts on Threatened and Endangered Species" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. May 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Lashley, Marcus. "Feral pigs harm wildlife and biodiversity as well as crops". The Conversation. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- "Hogs Gone Wild". National Wildlife Federation. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- By (1 July 2019). "Feral pigs are ruining ecosystems across 35 states and hunting is making it worse". Popular Science. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Jokelainen, P.; Velström, K.; Lassen, B. (2015). "Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in free-ranging wild boars hunted for human consumption in Estonia". Acta Vet Scand. 57: 42. doi:10.1186/s13028-015-0133-z. PMC 4524169. PMID 26239110.

- Cabanau 2001, pp. 63

- "FINLAND: Wet Threats". The New York Times. 14 December 1931.

- Suomen kunnallisvaakunat (in Finnish). Suomen Kunnallisliitto. 1982. p. 145. ISBN 951-773-085-3.

- Beresnevičius, Gintaras. "Aisčių mater deum klausimu". In: Liaudies kultūra 2006, Nr. 2, p. 6. ISSN 0236-0551 https://www.lituanistika.lt/content/4244

- Charles C. Mann, Göbekli Tepe: The Birth of Religion, National Geographic (June 2011)

- Sandra Scham The World's First Temple, Archaeology, Volume 61 Number 6, November/December 2008

- Mallory, J. P. & Adams, D. Q. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Taylor & Francis, pp. 426–428, ISBN 1-884964-98-2

- Smith, Evans Lansing (1997). The Hero Journey in Literature: Parables of Poesis. University Press of America. pp. 253–254. ISBN 978-0-761-80509-0.

- Scheggi 1999, pp. 14–15

- Scheggi 1999, pp. 16

- Kovářová, L. (2011). "The Swine in Old Nordic Religion and Worldview". Háskóla Íslands. S2CID 154250096. Retrieved 11 June 2022.