Biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic (genetic variability), species (species diversity), and ecosystem (ecosystem diversity) level.[1]

Biodiversity is not distributed evenly on Earth, it is usually greater in the tropics as a result of the warm climate and high primary productivity in the region near the equator. These tropical forest ecosystems cover less than 10% of earth's surface and contain about 90% of the world's species. Marine biodiversity is usually higher along coasts in the Western Pacific, where sea surface temperature is highest, and in the mid-latitudinal band in all oceans. There are latitudinal gradients in species diversity. Biodiversity generally tends to cluster in hotspots, and has been increasing through time, but will be likely to slow in the future as a primary result of deforestation. It encompasses the evolutionary, ecological, and cultural processes that sustain life.

Rapid environmental changes typically cause mass extinctions. More than 99.9% of all species that ever lived on Earth, amounting to over five billion species, are estimated to be extinct. Estimates on the number of Earth's current species range from 10 million to 14 million, of which about 1.2 million have been documented and over 86% have not yet been described. The total amount of related DNA base pairs on Earth is estimated at 5.0 x 1037 and weighs 50 billion tonnes. In comparison, the total mass of the biosphere has been estimated to be as much as four trillion tons of carbon. In July 2016, scientists reported identifying a set of 355 genes from the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) of all organisms living on Earth.

The age of the Earth is about 4.54 billion years. The earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates at least from 3.5 billion years ago, during the Eoarchean Era after a geological crust started to solidify following the earlier molten Hadean Eon. There are microbial mat fossils found in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone discovered in Western Australia. Other early physical evidence of a biogenic substance is graphite in 3.7 billion-year-old meta-sedimentary rocks discovered in Western Greenland. More recently, in 2015, "remains of biotic life" were found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia. According to one of the researchers, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth...then it could be common in the universe."[2]

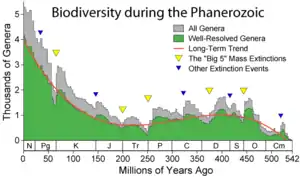

Since life began on Earth, five major mass extinctions and several minor events have led to large and sudden drops in biodiversity. The Phanerozoic aeon (the last 540 million years) marked a rapid growth in biodiversity via the Cambrian explosion—a period during which the majority of multicellular phyla first appeared. The next 400 million years included repeated, massive biodiversity losses classified as mass extinction events. In the Carboniferous, rainforest collapse led to a great loss of plant and animal life. The Permian–Triassic extinction event, 251 million years ago, was the worst; vertebrate recovery took 30 million years. The most recent, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, occurred 65 million years ago and has often attracted more attention than others because it resulted in the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs.

The period since the emergence of humans has displayed an ongoing biodiversity reduction and an accompanying loss of genetic diversity. Named the Holocene extinction, and often referred to as the sixth mass extinction, the reduction is caused primarily by human impacts, particularly habitat destruction. Conversely, biodiversity positively impacts human health in many ways, although a few negative effects are studied.

Naming and etymology

- 1916 – The term biological diversity was used first by J. Arthur Harris in "The Variable Desert," Scientific American: "The bare statement that the region contains a flora rich in genera and species and of diverse geographic origin or affinity is entirely inadequate as a description of its real biological diversity."[3]

- 1967 - Raymond F. Dasmann used the term biological diversity in reference to the richness of living nature that conservationists should protect in his book A Different Kind of Country.[4][5]

- 1974 – The term natural diversity was introduced by John Terborgh.[6]

- 1980 – Thomas Lovejoy introduced the term biological diversity to the scientific community in a book.[7] It rapidly became commonly used.[8]

- 1985 – According to Edward O. Wilson, the contracted form biodiversity was coined by W. G. Rosen: "The National Forum on BioDiversity ... was conceived by Walter G.Rosen ... Dr. Rosen represented the NRC/NAS throughout the planning stages of the project. Furthermore, he introduced the term biodiversity".[9]

- 1985 - The term "biodiversity" appears in the article, "A New Plan to Conserve the Earth's Biota" by Laura Tangley.[10]

- 1988 - The term biodiversity first appeared in publication.[11][12]

- The present – the term has achieved widespread use.

Definitions

"Biodiversity" is most commonly used to replace the more clearly-defined and long-established terms, species diversity and species richness.[13] Biologists most often define biodiversity as the "totality of genes, species and ecosystems of a region".[14][15] An advantage of this definition is that it presents a unified view of the traditional types of biological variety previously identified:

- taxonomic diversity (usually measured at the species diversity level)[16]

- ecological diversity (often viewed from the perspective of ecosystem diversity)[16]

- morphological diversity (which stems from genetic diversity and molecular diversity[17])

- functional diversity (which is a measure of the number of functionally disparate species within a population (e.g. different feeding mechanism, different motility, predator vs prey, etc.)[18]) This multilevel construct is consistent with Datman and Lovejoy.

Other definitions include:

- Wilcox 1982

- An explicit definition consistent with this interpretation was first given in a paper by Bruce A. Wilcox commissioned by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) for the 1982 World National Parks Conference.[19] Wilcox's definition was "Biological diversity is the variety of life forms...at all levels of biological systems (i.e., molecular, organismic, population, species and ecosystem)...".[19]

- Genetic

- Wilcox 1984

- Biodiversity can be defined genetically as the diversity of alleles, genes and organisms. They study processes such as mutation and gene transfer that drive evolution.[19]

- United Nations 1992

- The 1992 United Nations Earth Summit defined "biological diversity" as "the variability among living organisms from all sources, including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part: this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems".[20] This definition is used in the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity.[20]

- Gaston and Spicer 2004

- Gaston & Spicer's definition in their book "Biodiversity: an introduction" is "variation of life at all levels of biological organization".[21]

- Food and Agriculture Organization 2019

- The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines biodiversity as "the variability that exists among living organisms (both within and between species) and the ecosystems of which they are part."[22]

Forest biological biodiversity

Forest biological diversity is a broad term that refers to all life forms found within forested areas and the ecological roles they perform. As such, forest biological diversity encompasses not just trees, but the multitude of plants, animals and microorganisms that inhabit forest areas and their associated genetic diversity. Forest biological diversity can be considered at different levels, including ecosystem, landscape, species, population and genetic. Complex interactions can occur within and between these levels. In biologically diverse forests, this complexity allows organisms to adapt to continually changing environmental conditions and to maintain ecosystem functions.

In the annex to Decision II/9 (CBD, n.d.a), the Conference of the Parties to the CBD recognized that: "Forest biological diversity results from evolutionary processes over thousands and even millions of years which, in themselves, are driven by ecological forces such as climate, fire, competition and disturbance. Furthermore, the diversity of forest ecosystems (in both physical and biological features) results in high levels of adaptation, a feature of forest ecosystems which is an integral component of their biological diversity. Within specific forest ecosystems, the maintenance of ecological processes is dependent upon the maintenance of their biological diversity."[23]

Distribution

Biodiversity is not evenly distributed, rather it varies greatly across the globe as well as within regions. Among other factors, the diversity of all living things (biota) depends on temperature, precipitation, altitude, soils, geography and the presence of other species. The study of the spatial distribution of organisms, species and ecosystems, is the science of biogeography.[24][25]

Diversity consistently measures higher in the tropics and in other localized regions such as the Cape Floristic Region and lower in polar regions generally. Rain forests that have had wet climates for a long time, such as Yasuní National Park in Ecuador, have particularly high biodiversity.[26][27]

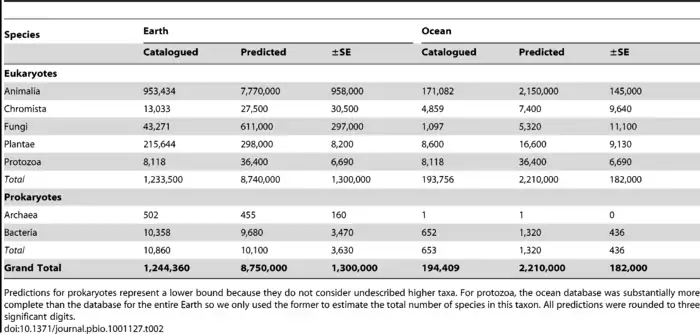

Terrestrial biodiversity is thought to be up to 25 times greater than ocean biodiversity.[28] Forests harbour most of Earth's terrestrial biodiversity. The conservation of the world's biodiversity is thus utterly dependent on the way in which we interact with and use the world's forests.[23] A new method used in 2011, put the total number of species on Earth at 8.7 million, of which 2.1 million were estimated to live in the ocean.[29] However, this estimate seems to under-represent the diversity of microorganisms.[30] Forests provide habitats for 80 percent of amphibian species, 75 percent of bird species and 68 percent of mammal species. About 60 percent of all vascular plants are found in tropical forests. Mangroves provide breeding grounds and nurseries for numerous species of fish and shellfish and help trap sediments that might otherwise adversely affect seagrass beds and coral reefs, which are habitats for many more marine species.[23]

The biodiversity of forests varies considerably according to factors such as forest type, geography, climate and soils – in addition to human use.[31] Most forest habitats in temperate regions support relatively few animal and plant species and species that tend to have large geographical distributions, while the montane forests of Africa, South America and Southeast Asia and lowland forests of Australia, coastal Brazil, the Caribbean islands, Central America and insular Southeast Asia have many species with small geographical distributions.[31] Areas with dense human populations and intense agricultural land use, such as Europe, parts of Bangladesh, China, India and North America, are less intact in terms of their biodiversity. Northern Africa, southern Australia, coastal Brazil, Madagascar and South Africa, are also identified as areas with striking losses in biodiversity intactness.[31]

Latitudinal gradients

Generally, there is an increase in biodiversity from the poles to the tropics. Thus localities at lower latitudes have more species than localities at higher latitudes. This is often referred to as the latitudinal gradient in species diversity. Several ecological factors may contribute to the gradient, but the ultimate factor behind many of them is the greater mean temperature at the equator compared to that of the poles.[32][33][34]

Even though terrestrial biodiversity declines from the equator to the poles,[35] some studies claim that this characteristic is unverified in aquatic ecosystems, especially in marine ecosystems.[36] The latitudinal distribution of parasites does not appear to follow this rule.[24]

In 2016, an alternative hypothesis ("the fractal biodiversity") was proposed to explain the biodiversity latitudinal gradient.[37] In this study, the species pool size and the fractal nature of ecosystems were combined to clarify some general patterns of this gradient. This hypothesis considers temperature, moisture, and net primary production (NPP) as the main variables of an ecosystem niche and as the axis of the ecological hypervolume. In this way, it is possible to build fractal hyper volumes, whose fractal dimension rises to three moving towards the equator.[38]

Biodiversity Hotspot

A biodiversity hotspot is a region with a high level of endemic species that have experienced great habitat loss.[39] The term hotspot was introduced in 1988 by Norman Myers.[40][41][42][43] While hotspots are spread all over the world, the majority are forest areas and most are located in the tropics.

Brazil's Atlantic Forest is considered one such hotspot, containing roughly 20,000 plant species, 1,350 vertebrates and millions of insects, about half of which occur nowhere else.[44][45] The island of Madagascar and India are also particularly notable. Colombia is characterized by high biodiversity, with the highest rate of species by area unit worldwide and it has the largest number of endemics (species that are not found naturally anywhere else) of any country. About 10% of the species of the Earth can be found in Colombia, including over 1,900 species of bird, more than in Europe and North America combined, Colombia has 10% of the world's mammals species, 14% of the amphibian species and 18% of the bird species of the world.[46] Madagascar dry deciduous forests and lowland rainforests possess a high ratio of endemism.[47][48] Since the island separated from mainland Africa 66 million years ago, many species and ecosystems have evolved independently.[49] Indonesia's 17,000 islands cover 735,355 square miles (1,904,560 km2) and contain 10% of the world's flowering plants, 12% of mammals and 17% of reptiles, amphibians and birds—along with nearly 240 million people.[50] Many regions of high biodiversity and/or endemism arise from specialized habitats which require unusual adaptations, for example, alpine environments in high mountains, or Northern European peat bogs.[48]

Accurately measuring differences in biodiversity can be difficult. Selection bias amongst researchers may contribute to biased empirical research for modern estimates of biodiversity. In 1768, Rev. Gilbert White succinctly observed of his Selborne, Hampshire "all nature is so full, that that district produces the most variety which is the most examined."[51]

Evolution

History

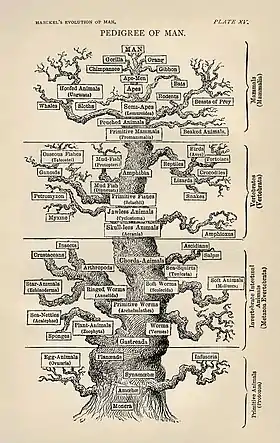

Biodiversity is the result of 3.5 billion years of evolution.[52] The origin of life has not been established by science, however, some evidence suggests that life may already have been well-established only a few hundred million years after the formation of the Earth. Until approximately 2.5 billion years ago, all life consisted of microorganisms – archaea, bacteria, and single-celled protozoans and protists.[30]

Life timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — | Water Single-celled life Photosynthesis H a d e a n |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(million years ago) *Ice Ages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The history of biodiversity during the Phanerozoic (the last 540 million years), starts with rapid growth during the Cambrian explosion—a period during which nearly every phylum of multicellular organisms first appeared.[54] Over the next 400 million years or so, invertebrate diversity showed little overall trend and vertebrate diversity shows an overall exponential trend.[16] This dramatic rise in diversity was marked by periodic, massive losses of diversity classified as mass extinction events.[16] A significant loss occurred when rainforests collapsed in the carboniferous.[55] The worst was the Permian-Triassic extinction event, 251 million years ago. Vertebrates took 30 million years to recover from this event.[56]

The biodivertisy of the past is called Paleobiodiversity. The fossil record suggests that the last few million years featured the greatest biodiversity in history.[16] However, not all scientists support this view, since there is uncertainty as to how strongly the fossil record is biased by the greater availability and preservation of recent geologic sections.[57] Some scientists believe that corrected for sampling artifacts, modern biodiversity may not be much different from biodiversity 300 million years ago,[54] whereas others consider the fossil record reasonably reflective of the diversification of life.[16] Estimates of the present global macroscopic species diversity vary from 2 million to 100 million, with a best estimate of somewhere near 9 million,[29] the vast majority arthropods.[58] Diversity appears to increase continually in the absence of natural selection.[59]

Diversification

The existence of a global carrying capacity, limiting the amount of life that can live at once, is debated, as is the question of whether such a limit would also cap the number of species. While records of life in the sea show a logistic pattern of growth, life on land (insects, plants and tetrapods) shows an exponential rise in diversity.[16] As one author states, "Tetrapods have not yet invaded 64 percent of potentially habitable modes and it could be that without human influence the ecological and taxonomic diversity of tetrapods would continue to increase exponentially until most or all of the available eco-space is filled."[16]

It also appears that the diversity continues to increase over time, especially after mass extinctions.[60]

On the other hand, changes through the Phanerozoic correlate much better with the hyperbolic model (widely used in population biology, demography and macrosociology, as well as fossil biodiversity) than with exponential and logistic models. The latter models imply that changes in diversity are guided by a first-order positive feedback (more ancestors, more descendants) and/or a negative feedback arising from resource limitation. Hyperbolic model implies a second-order positive feedback.[61] Differences in the strength of the second-order feedback due to different intensities of interspecific competition might explain the faster rediversification of ammonoids in comparison to bivalves after the end-Permian extinction.[61] The hyperbolic pattern of the world population growth arises from a second-order positive feedback between the population size and the rate of technological growth.[62] The hyperbolic character of biodiversity growth can be similarly accounted for by a feedback between diversity and community structure complexity.[62][63] The similarity between the curves of biodiversity and human population probably comes from the fact that both are derived from the interference of the hyperbolic trend with cyclical and stochastic dynamics.[62][63]

Most biologists agree however that the period since human emergence is part of a new mass extinction, named the Holocene extinction event, caused primarily by the impact humans are having on the environment.[64] It has been argued that the present rate of extinction is sufficient to eliminate most species on the planet Earth within 100 years.[65]

New species are regularly discovered (on average between 5–10,000 new species each year, most of them insects) and many, though discovered, are not yet classified (estimates are that nearly 90% of all arthropods are not yet classified).[58] Most of the terrestrial diversity is found in tropical forests and in general, the land has more species than the ocean; some 8.7 million species may exist on Earth, of which some 2.1 million live in the ocean.[29]

Ecosystem services

General ecosystem services

"Ecosystem services are the suite of benefits that ecosystems provide to humanity."[66] The natural species, or biota, are the caretakers of all ecosystems. It is as if the natural world is an enormous bank account of capital assets capable of paying life sustaining dividends indefinitely, but only if the capital is maintained.[67] These services come in three flavors:

- Provisioning services which involve the production of renewable resources (e.g.: food, wood, fresh water)[66]

- Regulating services which are those that lessen environmental change (e.g.: climate regulation, pest/disease control)[66]

- Cultural services represent human value and enjoyment (e.g.: landscape aesthetics, cultural heritage, outdoor recreation and spiritual significance)[68]

There have been many claims about biodiversity's effect on these ecosystem services, especially provisioning and regulating services.[66] After an exhaustive survey through peer-reviewed literature to evaluate 36 different claims about biodiversity's effect on ecosystem services, 14 of those claims have been validated, 6 demonstrate mixed support or are unsupported, 3 are incorrect and 13 lack enough evidence to draw definitive conclusions.[66]

Services enhanced

- Provisioning services

Greater species diversity

- of plants increases fodder yield (synthesis of 271 experimental studies).[25]

- of plants (i.e. diversity within a single species) increases overall crop yield (synthesis of 575 experimental studies).[69] Although another review of 100 experimental studies reports mixed evidence.[70]

- of trees increases overall wood production (Synthesis of 53 experimental studies).[71] However, there is not enough data to draw a conclusion about the effect of tree trait diversity on wood production.[66]

- Regulating services

Greater species diversity

- of fish increases the stability of fisheries yield (Synthesis of 8 observational studies)[66]

- of natural pest enemies decreases herbivorous pest populations (Data from two separate reviews; Synthesis of 266 experimental and observational studies;[72] Synthesis of 18 observational studies.[73][74] Although another review of 38 experimental studies found mixed support for this claim, suggesting that in cases where mutual intraguild predation occurs, a single predatory species is often more effective[75]

- of plants decreases disease prevalence on plants (Synthesis of 107 experimental studies)[76]

- of plants increases resistance to plant invasion (Data from two separate reviews; Synthesis of 105 experimental studies;[76] Synthesis of 15 experimental studies[77])

- of plants increases carbon sequestration, but note that this finding only relates to actual uptake of carbon dioxide and not long-term storage, see below; Synthesis of 479 experimental studies)[25]

- plants increases soil nutrient remineralization (Synthesis of 103 experimental studies)[76]

- of plants increases soil organic matter (Synthesis of 85 experimental studies)[76]

Services with mixed evidence

- Provisioning services

- None to date

- Regulating services

- Greater species diversity of plants may or may not decrease herbivorous pest populations. Data from two separate reviews suggest that greater diversity decreases pest populations (Synthesis of 40 observational studies;[78] Synthesis of 100 experimental studies).[70] One review found mixed evidence (Synthesis of 287 experimental studies[79]), while another found contrary evidence (Synthesis of 100 experimental studies[76])

- Greater species diversity of animals may or may not decrease disease prevalence on those animals (Synthesis of 45 experimental and observational studies),[80] although a 2013 study offers more support showing that biodiversity may in fact enhance disease resistance within animal communities, at least in amphibian frog ponds.[81] Many more studies must be published in support of diversity to sway the balance of evidence will be such that we can draw a general rule on this service.

- Greater species and trait diversity of plants may or may not increase long term carbon storage (Synthesis of 33 observational studies)[66]

- Greater pollinator diversity may or may not increase pollination (Synthesis of 7 observational studies),[66] but a publication from March 2013 suggests that increased native pollinator diversity enhances pollen deposition (although not necessarily fruit set as the authors would have you believe, for details explore their lengthy supplementary material).[82]

Services hindered

- Provisioning services

- Greater species diversity of plants reduces primary production (Synthesis of 7 experimental studies)[25]

- Regulating services

- greater genetic and species diversity of a number of organisms reduces freshwater purification (Synthesis of 8 experimental studies, although an attempt by the authors to investigate the effect of detritivore diversity on freshwater purification was unsuccessful due to a lack of available evidence (only 1 observational study was found[66]

- Effect of species diversity of plants on biofuel yield (In a survey of the literature, the investigators only found 3 studies)[66]

- Effect of species diversity of fish on fishery yield (In a survey of the literature, the investigators only found 4 experimental studies and 1 observational study)[66]

- Regulating services

- Effect of species diversity on the stability of biofuel yield (In a survey of the literature, the investigators did not find any studies)[66]

- Effect of species diversity of plants on the stability of fodder yield (In a survey of the literature, the investigators only found 2 studies)[66]

- Effect of species diversity of plants on the stability of crop yield (In a survey of the literature, the investigators only found 1 study)[66]

- Effect of genetic diversity of plants on the stability of crop yield (In a survey of the literature, the investigators only found 2 studies)[66]

- Effect of diversity on the stability of wood production (In a survey of the literature, the investigators could not find any studies)[66]

- Effect of species diversity of multiple taxa on erosion control (In a survey of the literature, the investigators could not find any studies – they did, however, find studies on the effect of species diversity and root biomass)[66]

- Effect of diversity on flood regulation (In a survey of the literature, the investigators could not find any studies)[66]

- Effect of species and trait diversity of plants on soil moisture (In a survey of the literature, the investigators only found 2 studies)[66]

Other sources have reported somewhat conflicting results and in 1997 Robert Costanza and his colleagues reported the estimated global value of ecosystem services (not captured in traditional markets) at an average of $33 trillion annually.[83]

Since the Stone Age, species loss has accelerated above the average basal rate, driven by human activity. Estimates of species losses are at a rate 100–10,000 times as fast as is typical in the fossil record.[84] Biodiversity also affords many non-material benefits including spiritual and aesthetic values, knowledge systems and education.[84]

Agriculture

Agricultural diversity can be divided into two categories: intraspecific diversity, which includes the genetic variation within a single species, like the potato (Solanum tuberosum) that is composed of many different forms and types (e.g. in the U.S. they might compare russet potatoes with new potatoes or purple potatoes, all different, but all part of the same species, S. tuberosum).

The other category of agricultural diversity is called interspecific diversity and refers to the number and types of different species. Thinking about this diversity we might note that many small vegetable farmers grow many different crops like potatoes and also carrots, peppers, lettuce, etc.

Agricultural diversity can also be divided by whether it is 'planned' diversity or 'associated' diversity. This is a functional classification that we impose and not an intrinsic feature of life or diversity. Planned diversity includes the crops which a farmer has encouraged, planted or raised (e.g. crops, covers, symbionts, and livestock, among others), which can be contrasted with the associated diversity that arrives among the crops, uninvited (e.g. herbivores, weed species and pathogens, among others).[85]

Associated biodiversity can be damaging or beneficial. The beneficial associated biodiversity include for instance wild pollinators such as wild bees and syrphid flies that pollinate crops[86] and natural enemies and antagonists to pests and pathogens. Beneficial associated biodiversity occurs abundantly in crop fields and provide multiple ecosystem services such as pest control, nutrient cycling and pollination that support crop production.[87]

The control of damaging associated biodiversity is one of the great agricultural challenges that farmers face. On monoculture farms, the approach is generally to suppress damaging associated diversity using a suite of biologically destructive pesticides, mechanized tools and transgenic engineering techniques, then to rotate crops. Although some polyculture farmers use the same techniques, they also employ integrated pest management strategies as well as more labor-intensive strategies, but generally less dependent on capital, biotechnology, and energy.

Interspecific crop diversity is, in part, responsible for offering variety in what we eat. Intraspecific diversity, the variety of alleles within a single species, also offers us a choice in our diets. If a crop fails in a monoculture, we rely on agricultural diversity to replant the land with something new. If a wheat crop is destroyed by a pest we may plant a hardier variety of wheat the next year, relying on intraspecific diversity. We may forgo wheat production in that area and plant a different species altogether, relying on interspecific diversity. Even an agricultural society that primarily grows monocultures relies on biodiversity at some point.

- The Irish potato blight of 1846 was a major factor in the deaths of one million people and the emigration of about two million. It was the result of planting only two potato varieties, both vulnerable to the blight, Phytophthora infestans, which arrived in 1845[85]

- When rice grassy stunt virus struck rice fields from Indonesia to India in the 1970s, 6,273 varieties were tested for resistance.[88] Only one was resistant, an Indian variety and known to science only since 1966.[88] This variety formed a hybrid with other varieties and is now widely grown.[88]

- Coffee rust attacked coffee plantations in Sri Lanka, Brazil and Central America in 1970. A resistant variety was found in Ethiopia.[89] The diseases are themselves a form of biodiversity.

Monoculture was a contributing factor to several agricultural disasters, including the European wine industry collapse in the late 19th century and the US southern corn leaf blight epidemic of 1970.[90]

Although about 80 percent of humans' food supply comes from just 20 kinds of plants,[91] humans use at least 40,000 species.[92] Earth's surviving biodiversity provides resources for increasing the range of food and other products suitable for human use, although the present extinction rate shrinks that potential.[65]

Human health

Biodiversity's relevance to human health is becoming an international political issue, as scientific evidence builds on the global health implications of biodiversity loss.[93][94][95] This issue is closely linked with the issue of climate change,[96] as many of the anticipated health risks of climate change are associated with changes in biodiversity (e.g. changes in populations and distribution of disease vectors, scarcity of fresh water, impacts on agricultural biodiversity and food resources etc.). This is because the species most likely to disappear are those that buffer against infectious disease transmission, while surviving species tend to be the ones that increase disease transmission, such as that of West Nile Virus, Lyme disease and Hantavirus, according to a study done co-authored by Felicia Keesing, an ecologist at Bard College and Drew Harvell, associate director for Environment of the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future (ACSF) at Cornell University.[97]

The growing demand and lack of drinkable water on the planet presents an additional challenge to the future of human health. Partly, the problem lies in the success of water suppliers to increase supplies and failure of groups promoting the preservation of water resources.[98] While the distribution of clean water increases, in some parts of the world it remains unequal. According to the World Health Organisation (2018), only 71% of the global population used a safely managed drinking-water service.[99]

Some of the health issues influenced by biodiversity include dietary health and nutrition security, infectious disease, medical science and medicinal resources, social and psychological health.[100] Biodiversity is also known to have an important role in reducing disaster risk and in post-disaster relief and recovery efforts.[101][102]

According to the United Nations Environment Programme a pathogen, like a virus, have more chances to meet resistance in a diverse population. Therefore, in a population genetically similar it expands more easily. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic had less chances to occur in a world with higher biodiversity.[103]

Biodiversity provides critical support for drug discovery and the availability of medicinal resources.[104][105] A significant proportion of drugs are derived, directly or indirectly, from biological sources: at least 50% of the pharmaceutical compounds on the US market are derived from plants, animals and microorganisms, while about 80% of the world population depends on medicines from nature (used in either modern or traditional medical practice) for primary healthcare.[94] Only a tiny fraction of wild species has been investigated for medical potential. Biodiversity has been critical to advances throughout the field of bionics. Evidence from market analysis and biodiversity science indicates that the decline in output from the pharmaceutical sector since the mid-1980s can be attributed to a move away from natural product exploration ("bioprospecting") in favour of genomics and synthetic chemistry, indeed claims about the value of undiscovered pharmaceuticals may not provide enough incentive for companies in free markets to search for them because of the high cost of development;[106] meanwhile, natural products have a long history of supporting significant economic and health innovation.[107][108] Marine ecosystems are particularly important,[109] although inappropriate bioprospecting can increase biodiversity loss, as well as violating the laws of the communities and states from which the resources are taken.[110][111][112]

Business and industry

.jpg.webp)

Many industrial materials derive directly from biological sources. These include building materials, fibers, dyes, rubber, and oil. Biodiversity is also important to the security of resources such as water, timber, paper, fiber, and food.[113][114][115] As a result, biodiversity loss is a significant risk factor in business development and a threat to long-term economic sustainability.[116][117]

Leisure, cultural and aesthetic value

Biodiversity enriches leisure activities such as birdwatching or natural history study.

Popular activities such as gardening and fishkeeping strongly depend on biodiversity. The number of species involved in such pursuits is in the tens of thousands, though the majority do not enter commerce.

The relationships between the original natural areas of these often exotic animals and plants and commercial collectors, suppliers, breeders, propagators and those who promote their understanding and enjoyment are complex and poorly understood. The general public responds well to exposure to rare and unusual organisms, reflecting their inherent value.

Philosophically it could be argued that biodiversity has intrinsic aesthetic and spiritual value to mankind in and of itself. This idea can be used as a counterweight to the notion that tropical forests and other ecological realms are only worthy of conservation because of the services they provide.[118]

Ecological services

Biodiversity supports many ecosystem services:

"There is now unequivocal evidence that biodiversity loss reduces the efficiency by which ecological communities capture biologically essential resources, produce biomass, decompose and recycle biologically essential nutrients... There is mounting evidence that biodiversity increases the stability of ecosystem functions through time... Diverse communities are more productive because they contain key species that have a large influence on productivity and differences in functional traits among organisms increase total resource capture... The impacts of diversity loss on ecological processes might be sufficiently large to rival the impacts of many other global drivers of environmental change... Maintaining multiple ecosystem processes at multiple places and times requires higher levels of biodiversity than does a single process at a single place and time."[66]

It plays a part in regulating the chemistry of our atmosphere and water supply. Biodiversity is directly involved in water purification, recycling nutrients and providing fertile soils. Experiments with controlled environments have shown that humans cannot easily build ecosystems to support human needs;[119] for example insect pollination cannot be mimicked, though there have been attempts to create artificial pollinators using unmanned aerial vehicles.[120] The economic activity of pollination alone represented between $2.1–14.6 billion in 2003.[121]

Number of species

According to Mora and colleagues, the total number of terrestrial species is estimated to be around 8.7 million while the number of oceanic species is much lower, estimated at 2.2 million. The authors note that these estimates are strongest for eukaryotic organisms and likely represent the lower bound of prokaryote diversity.[122] Other estimates include:

- 220,000 vascular plants, estimated using the species-area relation method[123]

- 0.7-1 million marine species[124]

- 10–30 million insects;[125] (of some 0.9 million we know today)[126]

- 5–10 million bacteria;[127]

- 1.5-3 million fungi, estimates based on data from the tropics, long-term non-tropical sites and molecular studies that have revealed cryptic speciation.[128] Some 0.075 million species of fungi had been documented by 2001;[129]

- 1 million mites[130]

- The number of microbial species is not reliably known, but the Global Ocean Sampling Expedition dramatically increased the estimates of genetic diversity by identifying an enormous number of new genes from near-surface plankton samples at various marine locations, initially over the 2004–2006 period.[131] The findings may eventually cause a significant change in the way science defines species and other taxonomic categories.[132][133]

Since the rate of extinction has increased, many extant species may become extinct before they are described.[134] Not surprisingly, in the animalia the most studied groups are birds and mammals, whereas fishes and arthropods are the least studied animals groups.[135]

Measuring biodiversity

A variety of objective means exist to empirically measure biodiversity. Each measure relates to a particular use of the data, and is likely to be associated with the variety of genes. Biodiversity is commonly measured in terms of taxonomic richness of a geographic area over a time interval.

Species loss rates

No longer do we have to justify the existence of humid tropical forests on the feeble grounds that they might carry plants with drugs that cure human disease. Gaia theory forces us to see that they offer much more than this. Through their capacity to evapotranspirate vast volumes of water vapor, they serve to keep the planet cool by wearing a sunshade of white reflecting cloud. Their replacement by cropland could precipitate a disaster that is global in scale.

During the last century, decreases in biodiversity have been increasingly observed. In 2007, German Federal Environment Minister Sigmar Gabriel cited estimates that up to 30% of all species will be extinct by 2050.[137] Of these, about one eighth of known plant species are threatened with extinction.[138] Estimates reach as high as 140,000 species per year (based on Species-area theory).[139] This figure indicates unsustainable ecological practices, because few species emerge each year. Almost all scientists acknowledge that the rate of species loss is greater now than at any time in human history, with extinctions occurring at rates hundreds of times higher than background extinction rates.[138][140][141] and expected to still grow in the upcoming years.[141][142][143] As of 2012, some studies suggest that 25% of all mammal species could be extinct in 20 years.[144]

In absolute terms, the planet has lost 58% of its biodiversity since 1970 according to a 2016 study by the World Wildlife Fund.[145] The Living Planet Report 2014 claims that "the number of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish across the globe is, on average, about half the size it was 40 years ago". Of that number, 39% accounts for the terrestrial wildlife gone, 39% for the marine wildlife gone and 76% for the freshwater wildlife gone. Biodiversity took the biggest hit in Latin America, plummeting 83 percent. High-income countries showed a 10% increase in biodiversity, which was canceled out by a loss in low-income countries. This is despite the fact that high-income countries use five times the ecological resources of low-income countries, which was explained as a result of a process whereby wealthy nations are outsourcing resource depletion to poorer nations, which are suffering the greatest ecosystem losses.[146]

A 2017 study published in PLOS One found that the biomass of insect life in Germany had declined by three-quarters in the last 25 years.[147] Dave Goulson of Sussex University stated that their study suggested that humans "appear to be making vast tracts of land inhospitable to most forms of life, and are currently on course for ecological Armageddon. If we lose the insects then everything is going to collapse."[148]

In 2020 the World Wildlife Foundation published a report saying that "biodiversity is being destroyed at a rate unprecedented in human history". The report claims that 68% of the population of the examined species were destroyed in the years 1970 – 2016.[149]

Threats

In 2006, many species were formally classified as rare or endangered or threatened; moreover, scientists have estimated that millions more species are at risk which have not been formally recognized. About 40 percent of the 40,177 species assessed using the IUCN Red List criteria are now listed as threatened with extinction—a total of 16,119.[151] The five main drivers to biodiversity loss are : habitat loss, invasive species, overexploitation (extreme hunting and fishing pressure), pollution, and climate change.

Jared Diamond describes an "Evil Quartet" of habitat destruction, overkill, introduced species and secondary extinctions.[152] Edward O. Wilson prefers the acronym HIPPO, standing for Habitat destruction, Invasive species, Pollution, human over-Population and Over-harvesting.[153][154]

According to the IUCN the main direct threats to conservation fall in 11 categories[155]

1. Residential & commercial development

- housing & urban areas (urban areas, suburbs, villages, vacation homes, shopping areas, offices, schools, hospitals)

- commercial & industrial areas (manufacturing plants, shopping centers, office parks, military bases, power plants, train & shipyards, airports)

- tourism & recreational areas (skiing, golf courses, sports fields, parks, campgrounds)

2. Farming activities

- agriculture (crop farms, orchards, vineyards, plantations, ranches)

- aquaculture (shrimp or finfish aquaculture, fish ponds on farms, hatchery salmon, seeded shellfish beds, artificial algal beds)

3. Energy production & mining

- renewable energy production (geothermal, solar, wind, & tidal farms)

- non-renewable energy production (oil and gas drilling)

- mining (fuel and minerals)

4. Transportation & service corridors

- service corridors (electrical & phone wires, aqueducts, oil & gas pipelines)

- transport corridors (roads, railroads, shipping lanes, and flight paths)

- collisions with the vehicles using the corridors

- associated accidents and catastrophes (oil spills, electrocution, fire)

5. Biological resource usages

- hunting (bushmeat, trophy, fur)

- persecution (predator control and pest control, superstitions)

- plant destruction or removal (human consumption, free-range livestock foraging, battling timber disease, orchid collection)

- logging or wood harvesting (selective or clear-cutting, firewood collection, charcoal production)

- fishing (trawling, whaling, live coral or seaweed or egg collection)

6. Human intrusions & activities that alter, destroy, simply disturb habitats and species from exhibiting natural behaviors

- recreational activities (off-road vehicles, motorboats, jet-skis, snowmobiles, ultralight planes, dive boats, whale watching, mountain bikes, hikers, birdwatchers, skiers, pets in recreational areas, temporary campsites, caving, rock-climbing)

- war, civil unrest, & military exercises (armed conflict, minefields, tanks & other military vehicles, training exercises & ranges, defoliation, munitions testing)

- illegal activities (smuggling, immigration, vandalism)

7. Natural system modifications

- fire suppression or creation (controlled burns, inappropriate fire management, escaped agricultural and campfires, arson)

- water management (dam construction & operation, wetland filling, surface water diversion, groundwater pumping)

- other modifications (land reclamation projects, shoreline rip-rap, lawn cultivation, beach construction and maintenance, tree-thinning in parks)

- removing/reducing human maintenance (mowing meadows, reduction in controlled burns, lack of indigenous management of key ecosystems, ceasing supplemental feeding of condors)

8. Invasive & problematic species, pathogens & genes

- invasive species (feral horses & household pets, zebra mussels, Miconia tree, kudzu, introduction for biocontrol)

- problematic native species (overabundant native deer or kangaroo, overabundant algae due to loss of native grazing fish, locust-type plagues)

- introduced genetic material (pesticide-resistant crops, genetically modified insects for biocontrol, genetically modified trees or salmon, escaped hatchery salmon, restoration projects using non-local seed stock)

- pathogens & microbes (plague affecting rodents or rabbits, Dutch elm disease or chestnut blight, Chytrid fungus affecting amphibians outside of Africa)

9. Pollution

- sewage (untreated sewage, discharges from poorly functioning sewage treatment plants, septic tanks, pit latrines, oil or sediment from roads, fertilizers and pesticides from lawns and golf courses, road salt)

- industrial & military effluents (toxic chemicals from factories, illegal dumping of chemicals, mine tailings, arsenic from gold mining, leakage from fuel tanks, PCBs in river sediments)

- agricultural & forestry effluents (nutrient loading from fertilizer run-off, herbicide run-off, manure from feedlots, nutrients from aquaculture, soil erosion)

- garbage & solid waste (municipal waste, litter & dumped possessions, flotsam & jetsam from recreational boats, waste that entangles wildlife, construction debris)

- air-borne pollutants (acid rain, smog from vehicle emissions, excess nitrogen deposition, radioactive fallout, wind dispersion of pollutants or sediments from farm fields, smoke from forest fires or wood stoves)

- excess energy (noise from highways or airplanes, sonar from submarines that disturbs whales, heated water from power plants, lamps attracting insects, beach lights disorienting turtles, atmospheric radiation from ozone holes)

10. Catastrophic geological events

- earthquakes, tsunamis, avalanches, landslides, & volcanic eruptions and gas emissions

11. Climate changes

- ecosystem encroachment (inundation of shoreline ecosystems & drowning of coral reefs from sea level rise, dune encroachment from desertification, woody encroachment into grasslands)

- changes in geochemical regimes (ocean acidification, changes in atmospheric CO2 affecting plant growth, loss of sediment leading to broad-scale subsidence)

- changes in temperature regimes (heat waves, cold spells, oceanic temperature changes, melting of glaciers/sea ice)

- changes in precipitation & hydrological regimes (droughts, rain timing, loss of snow cover, increased severity of floods)

- severe weather events (thunderstorms, tropical storms, hurricanes, cyclones, tornadoes, hailstorms, ice storms or blizzards, dust storms, erosion of beaches during storms)

Habitat destruction

Habitat destruction has played a key role in extinctions, especially in relation to tropical forest destruction.[156] Factors contributing to habitat loss include: overconsumption, overpopulation, land use change, deforestation,[157] pollution (air pollution, water pollution, soil contamination) and global warming or climate change.[158][159]

Habitat size and numbers of species are systematically related. Physically larger species and those living at lower latitudes or in forests or oceans are more sensitive to reduction in habitat area.[160] Conversion to "trivial" standardized ecosystems (e.g., monoculture following deforestation) effectively destroys habitat for the more diverse species that preceded the conversion. Even the simplest forms of agriculture affect diversity – through clearing/draining the land, discouraging weeds and "pests", and encouraging just a limited set of domesticated plant and animal species. In some countries, property rights[161] or lax law/regulatory enforcement are associated with deforestation and habitat loss.[162]

A 2007 study conducted by the National Science Foundation found that biodiversity and genetic diversity are codependent—that diversity among species requires diversity within a species and vice versa. "If anyone type is removed from the system, the cycle can break down and the community becomes dominated by a single species."[163] At present, the most threatened ecosystems occur in fresh water, according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005, which was confirmed by the "Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment" organised by the biodiversity platform and the French Institut de recherche pour le développement (MNHNP).[164]

Co-extinctions are a form of habitat destruction. Co-extinction occurs when the extinction or decline in one species accompanies similar processes in another, such as in plants and beetles.[165]

A 2019 report has revealed that bees and other pollinating insects have been wiped out of almost a quarter of their habitats across the United Kingdom. The population crashes have been happening since the 1980s and are affecting biodiversity. The increase in industrial farming and pesticide use, combined with diseases, invasive species, and climate change is threatening the future of these insects and the agriculture they support.[166]

In 2019, research was published showing that insects are destroyed by human activities like habitat destruction, pesticide poisoning, invasive species and climate change at a rate that will cause the collapse of ecological systems in the next 50 years if it cannot be stopped.[167]

Introduced and invasive species

Barriers such as large rivers, seas, oceans, mountains and deserts encourage diversity by enabling independent evolution on either side of the barrier, via the process of allopatric speciation. The term invasive species is applied to species that breach the natural barriers that would normally keep them constrained. Without barriers, such species occupy new territory, often supplanting native species by occupying their niches, or by using resources that would normally sustain native species.

The number of species invasions has been on the rise at least since the beginning of the 1900s. Species are increasingly being moved by humans (on purpose and accidentally). In some cases the invaders are causing drastic changes and damage to their new habitats (e.g.: zebra mussels and the emerald ash borer in the Great Lakes region and the lion fish along the North American Atlantic coast). Some evidence suggests that invasive species are competitive in their new habitats because they are subject to less pathogen disturbance.[168] Others report confounding evidence that occasionally suggest that species-rich communities harbor many native and exotic species simultaneously[169] while some say that diverse ecosystems are more resilient and resist invasive plants and animals.[170] An important question is, "do invasive species cause extinctions?" Many studies cite effects of invasive species on natives,[171] but not extinctions. Invasive species seem to increase local (i.e.: alpha diversity) diversity, which decreases turnover of diversity (i.e.: beta diversity). Overall gamma diversity may be lowered because species are going extinct because of other causes,[172] but even some of the most insidious invaders (e.g.: Dutch elm disease, emerald ash borer, chestnut blight in North America) have not caused their host species to become extinct. Extirpation, population decline and homogenization of regional biodiversity are much more common. Human activities have frequently been the cause of invasive species circumventing their barriers,[173] by introducing them for food and other purposes. Human activities therefore allow species to migrate to new areas (and thus become invasive) occurred on time scales much shorter than historically have been required for a species to extend its range.

Not all introduced species are invasive, nor all invasive species deliberately introduced. In cases such as the zebra mussel, invasion of US waterways was unintentional. In other cases, such as mongooses in Hawaii, the introduction is deliberate but ineffective (nocturnal rats were not vulnerable to the diurnal mongoose). In other cases, such as oil palms in Indonesia and Malaysia, the introduction produces substantial economic benefits, but the benefits are accompanied by costly unintended consequences.

Finally, an introduced species may unintentionally injure a species that depends on the species it replaces. In Belgium, Prunus spinosa from Eastern Europe leafs much sooner than its West European counterparts, disrupting the feeding habits of the Thecla betulae butterfly (which feeds on the leaves). Introducing new species often leaves endemic and other local species unable to compete with the exotic species and unable to survive. The exotic organisms may be predators, parasites, or may simply outcompete indigenous species for nutrients, water and light.

At present, several countries have already imported so many exotic species, particularly agricultural and ornamental plants, that their indigenous fauna/flora may be outnumbered. For example, the introduction of kudzu from Southeast Asia to Canada and the United States has threatened biodiversity in certain areas.[174] Nature offers effective ways to help mitigate climate change.[175]

Genetic pollution

Endemic species can be threatened with extinction[176] through the process of genetic pollution, i.e. uncontrolled hybridization, introgression and genetic swamping. Genetic pollution leads to homogenization or replacement of local genomes as a result of either a numerical and/or fitness advantage of an introduced species.[177] Hybridization and introgression are side-effects of introduction and invasion. These phenomena can be especially detrimental to rare species that come into contact with more abundant ones. The abundant species can interbreed with the rare species, swamping its gene pool. This problem is not always apparent from morphological (outward appearance) observations alone. Some degree of gene flow is normal adaptation and not all gene and genotype constellations can be preserved. However, hybridization with or without introgression may, nevertheless, threaten a rare species' existence.[178][179]

Overexploitation

Overexploitation occurs when a resource is consumed at an unsustainable rate. This occurs on land in the form of overhunting, excessive logging, poor soil conservation in agriculture and the illegal wildlife trade. Overexploitation can lead to resource destruction, including extinction. Artificially developed projects can cause damage to the surrounding environment

About 25% of world fisheries are now overfished to the point where their current biomass is less than the level that maximizes their sustainable yield.[180]

The overkill hypothesis, a pattern of large animal extinctions connected with human migration patterns, can be used to explain why megafaunal extinctions can occur within a relatively short time period.[181]

Hybridization, genetic pollution/erosion and food security

In agriculture and animal husbandry, the Green Revolution popularized the use of conventional hybridization to increase yield. Often hybridized breeds originated in developed countries and were further hybridized with local varieties in the developing world to create high yield strains resistant to local climate and diseases. Local governments and industry have been pushing hybridization. Formerly huge gene pools of various wild and indigenous breeds have collapsed causing widespread genetic erosion and genetic pollution. This has resulted in the loss of genetic diversity and biodiversity as a whole.[182]

Genetically modified organisms contain genetic material that is altered through genetic engineering. Genetically modified crops have become a common source for genetic pollution in not only wild varieties, but also in domesticated varieties derived from classical hybridization.[183][184][185][186][187]

Genetic erosion and genetic pollution have the potential to destroy unique genotypes, threatening future access to food security. A decrease in genetic diversity weakens the ability of crops and livestock to be hybridized to resist disease and survive changes in climate.[182]

Climate change

Global warming is a major threat to global biodiversity.[188][189] For example, coral reefs – which are biodiversity hotspots – will be lost within the century if global warming continues at the current rate.[190][191]

Climate change has proven to affect biodiversity and evidence supporting the altering effects is widespread. Increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide certainly affects plant morphology[192] and is acidifying oceans,[193] and temperature affects species ranges,[194][195][196] phenology,[197] and weather,[198] but, mercifully, the major impacts that have been predicted are still potential futures. We have not documented major extinctions yet, even as climate change drastically alters the biology of many species.

In 2004, an international collaborative study on four continents estimated that 10 percent of species would become extinct by 2050 because of global warming. "We need to limit climate change or we wind up with a lot of species in trouble, possibly extinct," said Dr. Lee Hannah, a co-author of the paper and chief climate change biologist at the Center for Applied Biodiversity Science at Conservation International.[199]

A recent study predicts that up to 35% of the world terrestrial carnivores and ungulates will be at higher risk of extinction by 2050 because of the joint effects of predicted climate and land-use change under business-as-usual human development scenarios.[200]

Climate change has advanced the time of evening when Brazilian free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) emerge to feed. This change is believed to be related to the drying of regions as temperatures rise. This earlier emergence exposes the bats to greater predation increased competition with other insectivores who feed in the twilight or daylight hours.[201]

Human overpopulation

The world's population numbered nearly 7.6 billion as of mid-2017 (which is approximately one billion more inhabitants compared to 2005) and is forecast to reach 11.1 billion in 2100.[202] Sir David King, former chief scientific adviser to the UK government, told a parliamentary inquiry: "It is self-evident that the massive growth in the human population through the 20th century has had more impact on biodiversity than any other single factor."[203][204] At least until the middle of the 21st century, worldwide losses of pristine biodiverse land will probably depend much on the worldwide human birth rate.[205]

Some top scientists have argued that population size and growth, along with overconsumption, are significant factors in biodiversity loss and soil degradation.[206][207] The 2019 IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services and biologists including Paul R. Ehrlich and Stuart Pimm have noted that human population growth and overconsumption are the main drivers of species decline.[208][209][210][211] E. O. Wilson, who contends that human population growth has been devastating to the planet's biodiversity, stated that the "pattern of human population growth in the 20th century was more bacterial than primate." He added that when Homo sapiens reached a population of six billion their biomass exceeded that of any other large land dwelling animal species that had ever existed by over 100 times, and that "we and the rest of life cannot afford another 100 years like that."[212]

According to a 2020 study by the World Wildlife Fund, the global human population already exceeds planet's biocapacity – it would take the equivalent of 1.56 Earths of biocapacity to meet our current demands.[213] The 2014 report further points that if everyone on the planet had the Footprint of the average resident of Qatar, we would need 4.8 Earths and if we lived the lifestyle of a typical resident of the US, we would need 3.9 Earths.[146]

The Holocene extinction

_relative_to_baseline_-_fcosc-01-615419-g001.jpg.webp)

Rates of decline in biodiversity in this sixth mass extinction match or exceed rates of loss in the five previous mass extinction events in the fossil record.[223] Loss of biodiversity results in the loss of natural capital that supplies ecosystem goods and services. From the perspective of the method known as Natural Economy the economic value of 17 ecosystem services for Earth's biosphere (calculated in 1997) has an estimated value of US$33 trillion (3.3x1013) per year.[224] Species today are being wiped out at a rate 100 to 1,000 times higher than baseline, and the rate of extinctions is increasing. This process destroys the resilience and adaptability of life on Earth.[225] The emergence of the sixth mass extinction is considered by conservation biologists, including Rodolfo Dirzo and Paul R. Ehrlich, to be "one of the most critical manifestations of the Anthropocene" and the continued decline of biodiversity constitutes "an unprecedented threat" to the continued existence of human civilization.[226]

In 2019, a summary for policymakers of the largest, most comprehensive study to date of biodiversity and ecosystem services, the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, was published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). The main conclusions:

1. Over the last 50 years, the state of nature has deteriorated at an unprecedented and accelerating rate.

2. The main drivers of this deterioration have been changes in land and sea use, exploitation of living beings, climate change, pollution, and invasive species. These five drivers, in turn, are caused by societal behaviors, from consumption to governance.

3. Damage to ecosystems undermines 35 of 44 selected UN targets, including the UN General Assembly's Sustainable Development Goals for poverty, hunger, health, water, cities' climate, oceans, and land. It can cause problems with food, water and humanity's air supply.

4. To fix the problem, humanity will need a transformative change, including sustainable agriculture, reductions in consumption and waste, fishing quotas and collaborative water management. On page 8 the report proposes on page 8 of the summary " enabling visions of a good quality of life that do not entail ever-increasing material consumption" as one of the main measures. The report states that "Some pathways chosen to achieve the goals related to energy, economic growth, industry and infrastructure and sustainable consumption and production (Sustainable Development Goals 7, 8, 9 and 12), as well as targets related to poverty, food security and cities (Sustainable Development Goals 1, 2 and 11), could have substantial positive or negative impacts on nature and therefore on the achievement of other Sustainable Development Goals".[227][228]

The October 2020 "Era of Pandemics" report by IPBES asserted that the same human activities which are the underlying drivers of climate change and biodiversity loss are also the same drivers of pandemics, including the COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Peter Daszak, Chair of the IPBES workshop, said "there is no great mystery about the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic – or of any modern pandemic . . . Changes in the way we use land; the expansion and intensification of agriculture; and unsustainable trade, production and consumption disrupt nature and increase contact between wildlife, livestock, pathogens and people. This is the path to pandemics."[229][230]

Conservation

Conservation biology matured in the mid-20th century as ecologists, naturalists and other scientists began to research and address issues pertaining to global biodiversity declines.[232][233][234]

The conservation ethic advocates management of natural resources for the purpose of sustaining biodiversity in species, ecosystems, the evolutionary process and human culture and society.[217][232][234][235][236]

Conservation biology is reforming around strategic plans to protect biodiversity.[232][237][238] Preserving global biodiversity is a priority in strategic conservation plans that are designed to engage public policy and concerns affecting local, regional and global scales of communities, ecosystems and cultures.[239] Action plans identify ways of sustaining human well-being, employing natural capital, market capital and ecosystem services.[240][241]

In the EU Directive 1999/22/EC zoos are described as having a role in the preservation of the biodiversity of wildlife animals by conducting research or participation in breeding programs.[242]

Protection and restoration techniques

Removal of exotic species will allow the species that they have negatively impacted to recover their ecological niches. Exotic species that have become pests can be identified taxonomically (e.g., with Digital Automated Identification SYstem (DAISY), using the barcode of life).[243][244] Removal is practical only given large groups of individuals due to the economic cost.

As sustainable populations of the remaining native species in an area become assured, "missing" species that are candidates for reintroduction can be identified using databases such as the Encyclopedia of Life and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

- Biodiversity banking places a monetary value on biodiversity. One example is the Australian Native Vegetation Management Framework.

- Gene banks are collections of specimens and genetic material. Some banks intend to reintroduce banked species to the ecosystem (e.g., via tree nurseries).[245]

- Reduction and better targeting of pesticides allows more species to survive in agricultural and urbanized areas.

- Location-specific approaches may be less useful for protecting migratory species. One approach is to create wildlife corridors that correspond to the animals' movements. National and other boundaries can complicate corridor creation.[246]

Protected areas

Protected areas, including forest reserves and biosphere reserves, serve many functions including for affording protection to wild animals and their habitat.[247] Protected areas have been set up all over the world with the specific aim of protecting and conserving plants and animals. Some scientists have called on the global community to designate as protected areas of 30 percent of the planet by 2030, and 50 percent by 2050, in order to mitigate biodiversity loss from anthropogenic causes.[248][249] In a study published 4 September 2020 in Science Advances researchers mapped out regions that can help meet critical conservation and climate goals.[250]

Protected areas safeguard nature and cultural resources and contribute to livelihoods, particularly at local level. There are over 238 563 designated protected areas worldwide, equivalent to 14.9 percent of the earth's land surface, varying in their extension, level of protection, and type of management (IUCN, 2018).[251]

Forest protected areas are a subset of all protected areas in which a significant portion of the area is forest.[23] This may be the whole or only a part of the protected area.[23] Globally, 18 percent of the world's forest area, or more than 700 million hectares, fall within legally established protected areas such as national parks, conservation areas and game reserves.[23]

The benefits of protected areas extend beyond their immediate environment and time. In addition to conserving nature, protected areas are crucial for securing the long-term delivery of ecosystem services. They provide numerous benefits including the conservation of genetic resources for food and agriculture, the provision of medicine and health benefits, the provision of water, recreation and tourism, and for acting as a buffer against disaster. Increasingly, there is acknowledgement of the wider socioeconomic values of these natural ecosystems and of the ecosystem services they can provide.[252]

Forest protected areas in particular play many important roles including as a provider of habitat, shelter, food and genetic materials, and as a buffer against disaster. They deliver stable supplies of many goods and environmental services. The role of protected areas, especially forest protected areas, in mitigating and adapting to climate change has increasingly been recognized over the last few years. Protected areas not only store and sequester carbon (i.e. the global network of protected areas stores at least 15 percent of terrestrial carbon), but also enable species to adapt to changing climate patterns by providing refuges and migration corridors. Protected areas also protect people from sudden climate events and reduce their vulnerability to weather-induced problems such as floods and droughts (UNEP–WCMC, 2016).

National parks

National park is a large natural or near natural areas set aside to protect large-scale ecological processes, which also provide a foundation for environmentally and culturally compatible, spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and visitor opportunities. These areas are selected by governments or private organizations to protect natural biodiversity along with its underlying ecological structure and supporting environmental processes, and to promote education and recreation. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and its World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA), has defined "National Park" as its Category II type of protected areas.[253]

National parks are usually owned and managed by national or state governments. In some cases, a limit is placed on the number of visitors permitted to enter certain fragile areas. Designated trails or roads are created. The visitors are allowed to enter only for study, cultural and recreation purposes. Forestry operations, grazing of animals and hunting of animals are regulated and the exploitation of habitat or wildlife is banned.

Wildlife sanctuary

Wildlife sanctuaries aim only at the conservation of species and have the following features:

- The boundaries of the sanctuaries are not limited by state legislation.

- The killing, hunting or capturing of any species is prohibited except by or under the control of the highest authority in the department which is responsible for the management of the sanctuary.

- Private ownership may be allowed.

- Forestry and other usages can also be permitted.

Forest reserves

There is an estimated 726 million ha of forest in protected areas worldwide. Of the six major world regions, South America has the highest share of forests in protected areas, 31 percent.[254]

The forests play a vital role in harboring more than 45,000 floral and 81,000 faunal species of which 5150 floral and 1837 faunal species are endemic.[255] In addition, there are 60,065 different tree species in the world.[256] Plant and animal species confined to a specific geographical area are called endemic species. In forest reserves, rights to activities like hunting and grazing are sometimes given to communities living on the fringes of the forest, who sustain their livelihood partially or wholly from forest resources or products. The unclassed forests cover 6.4 percent of the total forest area and they are marked by the following characteristics:

- They are large inaccessible forests.

- Many of these are unoccupied.

- They are ecologically and economically less important.

Steps to conserve the forest cover

- An extensive reforestation/afforestation programme should be followed.

- Alternative environment-friendly sources of fuel energy such as biogas other than wood should be used.

- Loss of biodiversity due to forest fire is a major problem, immediate steps to prevent forest fire need to be taken.

- Overgrazing by cattle can damage a forest seriously. Therefore, certain steps should be taken to prevent overgrazing by cattle.

- Hunting and poaching should be banned.

Zoological parks

In zoological parks or zoos, live animals are kept for public recreation, education and conservation purposes. Modern zoos offer veterinary facilities, provide opportunities for threatened species to breed in captivity and usually build environments that simulate the native habitats of the animals in their care. Zoos play a major role in creating awareness about the need to conserve nature.

Botanical gardens

In botanical gardens, plants are grown and displayed primarily for scientific and educational purposes. They consist of a collection of living plants, grown outdoors or under glass in greenhouses and conservatories. Also, a botanical garden may include a collection of dried plants or herbarium and such facilities as lecture rooms, laboratories, libraries, museums and experimental or research plantings.

Resource allocation

Focusing on limited areas of higher potential biodiversity promises greater immediate return on investment than spreading resources evenly or focusing on areas of little diversity but greater interest in biodiversity.[257]

A second strategy focuses on areas that retain most of their original diversity, which typically require little or no restoration. These are typically non-urbanized, non-agricultural areas. Tropical areas often fit both criteria, given their natively high diversity and relative lack of development.[258]

In society

In September 2020 scientists reported that "immediate efforts, consistent with the broader sustainability agenda but of unprecedented ambition and coordination, could enable the provision of food for the growing human population while reversing the global terrestrial biodiversity trends caused by habitat conversion" and recommend measures such as for addressing drivers of land-use change, and for increasing the extent of land under conservation management, efficiency in agriculture and the shares of plant-based diets.[259][260]

Citizen science

Citizen science, also known as public participation in scientific research, has been widely used in environmental sciences and is particularly popular in a biodiversity-related context. It has been used to enable scientists to involve the general public in biodiversity research, thereby enabling the scientists to collect data that they would otherwise not have been able to obtain. An online survey of 1,160 CS participants across 63 biodiversity citizen science projects in Europe, Australia and New Zealand reported positive changes in (a) content, process and nature of science knowledge, (b) skills of science inquiry, (c) self-efficacy for science and the environment, (d) interest in science and the environment, (e) motivation for science and the environment and (f) behaviour towards the environment.[261]

Volunteer observers have made significant contributions to on-the-ground knowledge about biodiversity, and recent improvements in technology have helped increase the flow and quality of occurrences from citizen sources. A 2016 study published in Biological Conservation[262] registers the massive contributions that citizen scientists already make to data mediated by the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). Despite some limitations of the dataset-level analysis, it's clear that nearly half of all occurrence records shared through the GBIF network come from datasets with significant volunteer contributions. Recording and sharing observations are enabled by several global-scale platforms, including iNaturalist and eBird.[263][264]

Legal status

International

- United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) and Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety;

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES);

- Ramsar Convention (Wetlands);

- Bonn Convention on Migratory Species;