History of Paris

The oldest traces of human occupation in Paris, discovered in 2008 near the Rue Henri-Farman in the 15th arrondissement, are human bones and evidence of an encampment of hunter-gatherers dating from about 8000 BC, during the Mesolithic period.[1] Between 250 and 225 BC, the Parisii, a sub-tribe of the Celtic Senones, settled on the banks of the Seine, built bridges and a fort, minted coins, and began to trade with other river settlements in Europe.[2]

| History of Paris |

|---|

|

|

| See also |

|

|

|

Roman Republic 52–27 BC

Roman Empire 27 BC–AD 395

Western Roman Empire 395–476

Kingdom of Soissons 476–486

Francia 486–843

West Francia 843–987

Kingdom of France 987–1792

French First Republic 1792–1804

First French Empire 1804–1814

Kingdom of France 1814–1815

First French Empire 1815

Kingdom of France 1815–1830

July Monarchy 1830–1848

French Second Republic 1848–1852

Second French Empire 1852–1870

French Third Republic 1870–1940

Military Administration in France 1940–1944

∟ part of German-occupied Europe from 1940 to 1944

Provisional Government of the French Republic 1944–1946

French Fourth Republic 1946–1958

French Fifth Republic 1958–present

In 52 BC, a Roman army led by Titus Labienus defeated the Parisii and established a Gallo-Roman garrison town called Lutetia.[3] The town was Christianised in the 3rd century AD, and after the collapse of the Roman Empire, it was occupied by Clovis I, the King of the Franks, who made it his capital in 508.

During the Middle Ages, Paris was the largest city in Europe, an important religious and commercial centre, and the birthplace of the Gothic style of architecture. The University of Paris on the Left Bank, organised in the mid-13th century, was one of the first in Europe. It suffered from the Bubonic Plague in the 14th century and the Hundred Years' War in the 15th century, with recurrence of the plague. Between 1418 and 1436, the city was occupied by the Burgundians and English soldiers. In the 16th century, Paris became the book-publishing capital of Europe, though it was shaken by the French Wars of Religion between Catholics and Protestants. In the 18th century, Paris was the centre of the intellectual ferment known as the Enlightenment, and the main stage of the French Revolution from 1789, which is remembered every year on the 14th of July with a military parade.

In the 19th century, Napoleon embellished the city with monuments to military glory. It became the European capital of fashion and the scene of two more revolutions (in 1830 and 1848). Under Napoleon III and his Prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the centre of Paris was rebuilt between 1852 and 1870 with wide new avenues, squares and new parks, and the city was expanded to its present limits in 1860. In the latter part of the century, millions of tourists came to see the Paris International Expositions and the new Eiffel Tower.

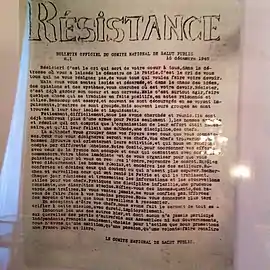

In the 20th century, Paris suffered bombardment in World War I and German occupation from 1940 until 1944 in World War II. Between the two wars, Paris was the capital of modern art and a magnet for intellectuals, writers and artists from around the world. The population reached its historic high of 2.1 million in 1921, but declined for the rest of the century. New museums (The Centre Pompidou, Musée Marmottan Monet and Musée d'Orsay) were opened, and the Louvre given its glass pyramid.

In the 21st century, Paris added new museums and a new concert hall, but in 2005 it also experienced violent unrest in the housing projects in the surrounding banlieues (suburbs), inhabited largely by first and second generation immigrants from France's former colonies in the Maghreb and Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2015, the city and the nation were shocked by two deadly terrorist attacks carried out by Islamic extremists. The population of the city declined steadily from 1921 until 2004, due to a decrease in family size and an exodus of the middle class to the suburbs; but it is increasing slowly once again, as young people and immigrants move into the city.

Prehistory

In 2008, archaeologists of the Institut national de recherches archéologiques préventives (INRAP) (administered by France's Ministry of Higher Education and Research) digging at n° 62 Rue Henri-Farman in the 15th arrondissement, not far from the Left Bank of the Seine, discovered the oldest human remains and traces of a hunter-gatherer settlement in Paris, dating to about 8000 BC, during the Mesolithic period.[1]

Other more recent traces of temporary settlements had been found at Bercy in 1991, dating from around 4500–4200 BC.[4] The excavations at Bercy found the fragments of three wooden canoes used by fishermen on the Seine, the oldest dating to 4800-4300 BC. They are now on display at the Carnavalet Museum.[5][6][7] Excavations at the Rue Henri-Farman site found traces of settlements from the middle Neolithic period (4200-3500 BC); the early Bronze Age (3500-1500 BC); and the first Iron Age (800-500 BC). The archaeologists found ceramics, animal bone fragments, and pieces of polished axes.[8] Hatchets made in eastern Europe were found at the Neolithic site in Bercy, showing that first Parisians were already trading with settlements in other parts of Europe.[9]

The Parisii and the Roman conquest (250–52 BC)

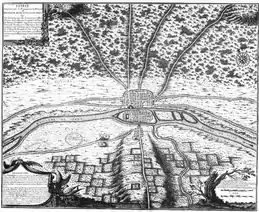

Between 250 and 225 BC, during the Iron Age, the Parisii, a sub-tribe of the Celtic Senones, settled on the banks of the Seine. At the beginning of the 2nd century BC, they built an oppidum, a walled fort, whose location is disputed. It may have been on the Île de la Cité, where bridges of an important trading route crossed the Seine. In his account of the Gallic wars, Julius Caesar recorded meeting with the leaders of the Parisii on an island in the Seine. Other historians cite an absence of traces of an early Gallic settlement on the island, and believe the oppidum was actually in Nanterre, in the Paris suburbs, where vestiges of a large settlement were discovered during construction of a highway in the 1980s.[10][2][11]

The settlement was called "Lucotocia" (according to the ancient Greek geographer Strabo) or "Leucotecia" (according to Roman geographer Ptolemy), and may have taken its name from the Celtic word lugo or luco, for a marsh or swamp.[12] It had a strategic position on the main trade route, via the Seine and Rhône rivers, between Britain and to the Roman colony of Provence and the Mediterranean Sea.[13][14] The location and the fees for crossing the bridge and passing along the river made the town prosperous,[15] so much so that it was able to mint its own gold coins.

Julius Caesar and his Roman army campaigned in Gaul between 58 and 53 BC under the pretext of protecting the territory from Germanic invaders, but in reality to conquer it and annex it to the Roman Republic.[16] In the summer of 53 BC, he visited the city and addressed the delegates of the Gallic tribes assembled before the temple to ask them to contribute soldiers and money to his campaign.[17] Wary of the Romans, the Parisii listened politely to Caesar, offered to provide some cavalry, but formed a secret alliance with the other Gallic tribes, under the leadership of Vercingetorix, and launched an uprising against the Romans in January 52 BC.[18]

Caesar responded quickly. He force-marched six legions north to Orléans, where the rebellion had begun, and then to Gergovia, the home of Vercingetorix. At the same time, he sent his deputy Titus Labienus with four legions to subdue the Parisii and their allies, the Senons. The Commander of the Parisii, Camulogene, burned the bridge that connected the oppidum to the left bank of the Seine, so the Romans were unable to approach the town. Then Labienus and the Romans went downstream, built their own pontoon bridge at Melun and approached Lutetia on the right bank. Camulogene responded by burning the bridge to the right bank and burning the town, before retreating to the left bank and making camp at what is now Saint-Germain-des-Prés.[3]

Labienus deceived the Parisii with a ruse. In the middle of the night he sent part of his army, making as much noise as possible, upstream to Melun. He left his most inexperienced soldiers in their camp on the right bank. With his best soldiers, he quietly crossed the Seine to the left bank and laid a trap for the Parisii. Camulogene, believing that the Romans were retreating, divided his own forces, some to capture the Roman camp, which he thought was abandoned, and others to pursue the Roman army. Instead he ran directly into the best two Roman legions on the plain of Grenelle, near the site of the modern Eiffel Tower and the École Militaire. The Parisii fought bravely and desperately in what became known as the Battle of Lutetia. Camulogene was killed and his soldiers were cut down by the disciplined Romans. Despite the defeat, the Parisii continued to resist the Romans. They sent eight thousand men to fight with Vercingetorix in his last stand against the Romans at the Battle of Alesia.[3]

Roman Lutetia (52 BC–486 AD)

-CNG.jpg.webp)

The Romans built an entirely new city as a base for their soldiers and the Gallic auxiliaries intended to keep an eye on the rebellious province. The new city was called Lutetia (Lutèce) or "Lutetia Parisiorum" ("Lutèce of the Parisii"). The name probably came from the Latin word luta, meaning mud or swamp[19] Caesar had described the great marsh, or marais, along the right bank of the Seine.[20] The major part of the city was on the left bank of the Seine, which was higher and less prone to flood. It was laid out following the traditional Roman town design along a north–south axis (known in Latin as the cardo maximus).[21]

On the left bank, the main Roman street followed the route of the modern day Rue Saint-Jacques. It crossed the Seine and traversed the Île de la Cité on two wooden bridges: the "Petit Pont" and the "Grand Pont" (today's Pont Notre-Dame). The port of the city, where the boats docked, was located on the island where the parvis of Notre Dame is today. On the right bank, it followed the modern Rue Saint-Martin.[21] On the left bank, the cardo was crossed by a less-important east–west decumanus, today's Rue Cujas, Rue Soufflot and Rue des Écoles.

The city was centered on the forum atop the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève between the Boulevard Saint-Michel and the Rue Saint-Jacques, where the Rue Soufflot is now located. The main building of the forum was one hundred meters long and contained a temple, a basilica used for civic functions and a square portico which covered shops. Nearby, on the slope of the hill, was an enormous amphitheatre built in the 1st century AD, which could seat ten to fifteen thousand spectators, though the population of the city was only six to eight thousand.[22]

Fresh drinking water was supplied to the city by an aqueduct sixteen kilometres long from the basin of Rungis and Wissous. The aqueduct also supplied water to the famous baths, or Thermes de Cluny, built near the forum at the end of the 2nd century or beginning of the 3rd century. Under Roman rule, the town was thoroughly Romanised and grew considerably.

Besides the Roman architecture and city design, the newcomers imported Roman cuisine: modern excavations have found amphorae of Italian wine and olive oil, shellfish, and a popular Roman sauce called garum.[21] Despite its commercial importance, Lutetia was only a medium-sized Roman city, considerably smaller than Lugdunum (Lyon) or Agedincum (Sens), which was the capital of the Roman province of Lugdunensis Quarta, in which Lutetia was located.[23]

Christianity was introduced into Paris in the middle of the 3rd century AD. According to tradition, it was brought by Saint Denis, the Bishop of the Parisii, who, along with two others, Rustique and Éleuthère, was arrested by the Roman prefect Fescennius. When he refused to renounce his faith, he was beheaded on Mount Mercury. According to the tradition, Saint Denis picked up his head and carried it to a secret Christian cemetery of Vicus Cattulliacus about six miles away. A different version of the legend says that a devout Christian woman, Catula, came at night to the site of the execution and took his remains to the cemetery. The hill where he was executed, Mount Mercury, later became the Mountain of Martyrs ("Mons Martyrum"), eventually Montmartre.[24] A church was built on the site of the grave of St. Denis, which later became the Basilica of Saint-Denis. By the 4th century, the city had its first recognized bishop, Victorinus (346 AD). By 392 AD, it had a cathedral.[25]

Late in the 3rd century AD, the invasion of Germanic tribes, beginning with the Alamans in 275 AD, caused many of the residents of the Left Bank to leave that part of the city and move to the safety of the Île de la Cité. Many of the monuments on the Left Bank were abandoned, and the stones used to build a wall around the Île de la Cité, the first city wall of Paris. A new basilica and baths were built on the island; their ruins were found beneath the square in front of the cathedral of Notre Dame.[26] Beginning in 305 AD, the name Lutetia was replaced on milestones by Civitas Parisiorum, or "City of the Parisii". By the period of the Late Roman Empire (the 3rd-5th centuries AD), it was known simply as "Parisius" in Latin and "Paris" in French.[27]

From 355 until 360, Paris was ruled by Julian, the nephew of Constantine the Great and the Caesar, or governor, of the western Roman provinces. When he was not campaigning with the army, he spent the winters of 357-358 and 358-359 in the city living in a palace on the site of the modern Palais de Justice, where he spent his time writing and establishing his reputation as a philosopher. In February 360, his soldiers proclaimed him Augustus, or Emperor, and for a brief time, Paris was the capital of the western Roman Empire, until he left in 363 and died fighting the Persians.[28][29] Two other emperors spent winters in the city near the end of the Roman Empire while trying to halt the tide of Barbarian invasions: Valentinian I (365–367) and Gratian in 383 AD.[25]

The gradual collapse of the Roman empire due to the increasing Germanic invasions of the 5th century, sent the city into a period of decline. In 451 AD, the city was threatened by the army of Attila the Hun, which had pillaged Treves, Metz and Reims. The Parisians were planning to abandon the city, but they were persuaded to resist by Saint Geneviève (422–502). Attila bypassed Paris and attacked Orléans. In 461, the city was threatened again by the Salian Franks led by Childeric I (436–481). The siege of the city lasted ten years. Once again, Geneviève organized the defense. She rescued the city by bringing wheat to the hungry city from Brie and Champagne on a flotilla of eleven barges. She became the patron saint of Paris shortly after her death.[30]

The Franks, a Germanic-speaking tribe, moved into northern Gaul as Roman influence declined. Frankish leaders were influenced by Rome, some even fought with Rome to defeat Atilla the Hun. The Franks worshipped the German gods such as Thor. Frankish laws and customs became the basis of French law and customs (Frankish laws were known as salic, meaning 'salt' or 'sea', law).[31]

Latin was no longer the language of everyday speech. The Franks became more politically influential and built up a large army. In 481, the son of Childeric, Clovis I, just sixteen years old, became the new ruler of the Franks. In 486, he defeated the last Roman armies, became the ruler of all of Gaul north of the river Loire and entered Paris. Before an important battle against the Burgundians, he took an oath to convert to Catholicism if he should win.[32]

He won the battle, and was converted to Christianity by his wife Clotilde, and was baptised at Reims in 496. His conversion to Christianity was likely seen as a title only, to improve his political position. He did not reject the pagan gods and their myths and rituals.[33] Clovis helped to drive the Visigoths out of Gaul. He was a king with no fixed capital and no central administration beyond his entourage. By deciding to be interred at Paris, Clovis gave the city symbolic weight. When his grandchildren divided royal power 50 years after his death in 511 , Paris was kept as a joint property and a fixed symbol of the dynasty.[34]

A model of the Thermes de Cluny, the Roman baths.

A model of the Thermes de Cluny, the Roman baths. The Roman baths today, now part of the Cluny Museum

The Roman baths today, now part of the Cluny Museum A Gallo-Roman toga clasp from the late 4th century. Lutetia was famous for its jewelers and craftsmen.

A Gallo-Roman toga clasp from the late 4th century. Lutetia was famous for its jewelers and craftsmen.

From Clovis to the Capetian kings (6th–11th centuries)

Clovis I and his successors of the Merovingian dynasty built a host of religious edifices in Paris: a basilica on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, near the site of the ancient Roman Forum; the cathedral of Saint-Étienne, where Notre Dame now stands; and several important monasteries, including one in the fields of the Left Bank that later became the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. They also built the Basilica of Saint-Denis, which became the necropolis of the kings of France. None of the Merovingian buildings survived, but there are four marble Merovingian columns in the church of Saint-Pierre de Montmartre.[35] The kings of the Merovingian dynasty were buried in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des Prés, however Dagobert I, the last king of the Merovingian dynasty, who died in 639, was the first Frankish king to be buried in the Basilica of Saint-Denis.

The kings of the Carolingian dynasty, who came to power in 751, moved the Frankish capital to Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) and paid little attention to Paris, though King Pepin the Short did build an impressive new sanctuary at Saint-Denis, which was consecrated in the presence of Charlemagne on 24 February 775.[36]

In the 9th century, the city was repeatedly attacked by the Vikings, who sailed up the Seine on great fleets of Viking ships. They demanded a ransom and ravaged the fields. In 857, Björn Ironside almost destroyed the city. In 885–886, they laid a one-year siege to Paris and tried again in 887 and in 889, but were unable to conquer the city, as it was protected by the Seine and the walls of the Île de la Cité.[37] The two bridges, vital to the city, were additionally protected by two massive stone fortresses, the Grand Châtelet on the Right Bank and the "Petit Châtelet" on the Left Bank, built on the initiative of Joscelin, the bishop of Paris. The Grand Châtelet gave its name to the modern Place du Châtelet on the same site.[38][37]

In the fall of 978, Paris was besieged by the Emperor Otto II during the Franco-German war of 978–980. At the end of the 10th century, a new dynasty of kings, the Capetians, founded by Hugh Capet in 987, came to power. Though they spent little time in the city, they restored the royal palace on the Île de la Cité and built a church where the Sainte-Chapelle stands today. Prosperity returned gradually to the city and the Right Bank began to be populated. On the Left Bank, the Capetians founded an important monastery: the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Its church was rebuilt in the 11th century. The monastery owed its fame to its scholarship and illuminated manuscripts.

Middle Ages (12th–15th centuries)

At the beginning of the 12th century, the French kings of the Capetian dynasty controlled little more than Paris and the surrounding region, but they did their best to build up Paris as the political, economic, religious and cultural capital of France.[37] The distinctive character of the city's districts continued to emerge at this time. The Île de la Cité was the site of the royal palace, and construction of the new Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris began in 1163.[39]

The Left Bank (south of the Seine) was the site of the new University of Paris established by the Church and royal court to train scholars in theology, mathematics and law, and the two great monasteries of Paris: the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés and the Abbey of Saint Geneviève.[40][39][37] The Right Bank (north of the Seine) became the centre of commerce and finance, where the port, the central market, workshops and the houses of merchants were located. A league of merchants, the Hanse parisienne, was established and quickly became a powerful force in the city's affairs.

The royal palace and the Louvre

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, the royal residence was on the Île de la Cité. Between 1190 and 1202, King Philip II built the massive fortress of the Louvre, which was designed to protect the Right Bank against an English attack from Normandy. The fortified castle was a great rectangle of 72 by 78 metres, with four towers, and surrounded by a moat. In the centre was a circular tower thirty meters high. The foundations can be seen today in the basement of the Louvre Museum.

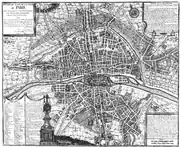

Before he departed for the Third Crusade, Philip II began construction of new fortifications for the city. He built a stone wall on the Left Bank, with thirty round towers. On the Right Bank, the wall extended for 2.8 kilometers, with forty towers to protect the new neighbourhoods of the growing medieval city. Many pieces of the wall can still be seen today, particularly in the Le Marais district. His third great project, much appreciated by the Parisians, was to pave the foul-smelling mud streets with stone. Over the Seine, he also rebuilt two wooden bridges in stone, the Petit-Pont and Grand-Pont, and he began construction on the Right Bank of a covered market, Les Halles.[41]

King Philip IV (r. 1285-1314) reconstructed the royal residence on the Île de la Cité, transforming it into a palace. Two of the great ceremonial halls still remain within the structure of the Palais de Justice. He also built a more sinister structure, the Gibbet of Montfaucon, near the modern Place du Colonel Fabien and the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, where the corpses of executed criminals were displayed. On 13 October 1307, he used his royal power to arrest the members of the Knights Templar, who, he felt, had grown too powerful, and on 18 March 1314, he had the Grand Master of the Order, Jacques de Molay, burned at the stake on the western point of the Île de la Cité.[42]

Between 1356 and 1383, King Charles V built a new wall of fortifications around the city: an important portion of this wall discovered during archaeological diggings in 1991-1992 can be seen within the Louvre complex, under the Place du Carrousel. He also built the Bastille, a large fortress guarding the Porte Saint-Antoine at the eastern end of Paris, and an imposing new fortress at Vincennes, east of city.[43] Charles V moved his official residence from the Île de la Cité to the Louvre, but preferred to live in the Hôtel Saint-Pol, his beloved residence.

Saint-Denis, Notre-Dame and the birth of the Gothic style

The flourishing of religious architecture in Paris was largely the work of Suger, the abbot of Saint-Denis from 1122–1151 and an advisor to Kings Louis VI and Louis VII. He rebuilt the façade of the old Carolingian Basilica of Saint Denis, dividing it into three horizontal levels and three vertical sections to symbolize the Holy Trinity. Then, from 1140 to 1144, he rebuilt the rear of the church with a majestic and dramatic wall of stained glass windows that flooded the church with light. This style, which later was named Gothic, was copied by other Paris churches: the Priory of Saint-Martin-des-Champs, Saint-Pierre de Montmartre, and Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and quickly spread to England and Germany.[44][45]

An even more ambitious building project, a new cathedral for Paris, was begun by bishop Maurice de Sully in about 1160, and it continued for two centuries. The first stone of the choir of the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris was laid in 1163, and the altar was consecrated in 1182. The façade was built between 1200 and 1225, and the two towers were built between 1225 and 1250. It was an immense structure, 125 metres long, with towers 63 meters high and seats for 1300 worshippers. The plan of the cathedral was copied on a smaller scale on the Left Bank of the Seine in the church of Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre.[46][47]

In the 13th century, King Louis IX (r. 1226–1270), known to history as "Saint Louis", built the Sainte-Chapelle, a masterpiece of Gothic architecture, especially to house relics from the crucifixion of Christ. Built between 1241 and 1248, it has the oldest stained glass windows preserved in Paris. At the same time that the Saint-Chapelle was built, the great stained glass rose windows, eighteen meters high, were added to the transept of the cathedral.[41]

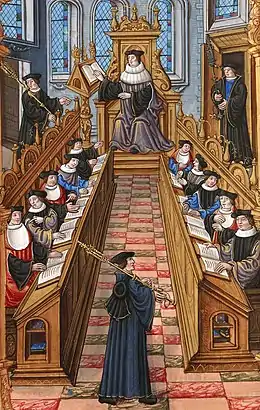

The University

Under Kings Louis VI and Louis VII, Paris became one of the principal centers of learning in Europe. Students, scholars and monks flocked to the city from England, Germany and Italy to engage in intellectual exchanges, to teach and be taught. They studied first in the different schools attached to Notre-Dame and the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The most famous teacher was Pierre Abelard (1079–1142), who taught five thousand students at the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. The University of Paris was originally organised in the mid-12th century as a guild or corporation of students and teachers. It was recognised by King Philip II in 1200 and officially recognised by Pope Innocent III, who had studied there, in 1215.[48]

Some twenty thousand students lived on the Left Bank, which became known as the Latin Quarter, because Latin was the language of instruction at the university and the common language in which the foreign students could converse. The poorer students lived in colleges (Collegia pauperum magistrorum), which were hotels where they were lodged and fed. In 1257, the chaplain of Louis IX, Robert de Sorbon, opened the oldest and most famous College of the University, which was later named after him, the Sorbonne.[48] From the 13th to the 15th century, the University of Paris was the most important school of Roman Catholic theology in western Europe. Its teachers included Roger Bacon from England, Saint Thomas Aquinas from Italy, and Saint Bonaventure from Germany.[37][44]

The Paris merchants

Beginning in the 11th century, Paris had been governed by a Royal Provost, appointed by the king, who lived in the fortress of Grand Châtelet. Saint Louis created a new position, the Provost of the Merchants (prévôt des marchands), to share authority with the Royal Provost and recognize the growing power and wealth of the merchants of Paris. The importance of guilds of craftsmen was reflected in the gesture of the city government to adapt its coat of arms, featuring a ship, from the symbol of the guild of the boatmen. Saint Louis created the first municipal council of Paris, with twenty-four members.

In 1328, Paris's population was about 200,000, which made it the most populous city in Europe. With the growth in population came growing social tensions; the first riots took place in December 1306 against the Provost of the Merchants, who was accused of raising rents. The houses of many merchants were burned, and twenty-eight rioters were hanged. In January 1357, Étienne Marcel, the Provost of Paris, led a merchants' revolt using violence (such as the killing of the councillors of the dauphin before his very eyes) in a bid to curb the power of the monarchy and obtain privileges for the city and the Estates General, which had met for the first time in Paris in 1347. After initial concessions by the Crown, the city was retaken by royalist forces in 1358. Marcel was killed and his followers dispersed (a number of which were later put to death).[49]

Plague and war

In the middle of the 14th century, Paris was struck by two great catastrophes: the Bubonic plague and the Hundred Years' War. In the first epidemic of the plague in 1348–1349, forty to fifty thousand Parisians died, a quarter of the population. The plague returned in 1360–61, 1363, and 1366–1368.[50][43] During the 16th and 17th centuries, plague visited the city almost one year out of three.[51]

The war was even more catastrophic. Beginning in 1346, the English army of King Edward III pillaged the countryside outside the walls of Paris. Ten years later, when King John II was captured by the English at the Battle of Poitiers, disbanded groups of mercenary soldiers looted and ravaged the surroundings of Paris.

More misfortunes followed. An English army and its allies from the Duchy of Burgundy invaded Paris during the night of 28–29 May 1418. Beginning in 1422, the north of France was ruled by John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, the regent for the infant King Henry VI of England, who was resident in Paris while King Charles VII of France only ruled France south of the Loire River. During her unsuccessful attempt at taking Paris on 8 September 1429, Joan of Arc was wounded just outside the Porte Saint-Honoré, the westernmost fortified entrance of the Wall of Charles V, not far from the Louvre.[43]

Due to the wars of Henry V on France, Paris fell to the English between 1420–1436, even the child king Henry VI was crowned the king of France there in 1431.[52] When the English left Paris in 1436, Charles VII was finally able to return. Many areas of the capital of his kingdom were in ruins, and a hundred thousand of its inhabitants, half the population, had left the city.

When Paris was again the capital of France, the succeeding monarchs chose to live in the Loire Valley and visited Paris only on special occasions.[53] King Francis I finally returned the royal residence to Paris in 1528.

Besides the Louvre, Notre-Dame and several churches, two large residences from the Middle Ages can still be seen in Paris: the Hôtel de Sens, built at the end of the 15th century as the residence of the Archbishop of Sens, and the Hôtel de Cluny, built in the years 1485–1510, which was the former residence of the abbot of the Cluny Monastery, but now houses the Museum of the Middle Ages. Both buildings were much modified in the centuries that followed. The oldest surviving house in Paris is the house of Nicolas Flamel built in 1407, which is located at 51 Rue de Montmorency. It was not a private home, but a hostel for the poor.[49]

16th century

By 1500, Paris had regained its former prosperity, and the population reached 250,000. Each new king of France added buildings, bridges and fountains to embellish his capital, most of them in the new Renaissance style imported from Italy.

King Louis XII rarely visited Paris, but he rebuilt the old wooden Pont Notre Dame, which had collapsed on 25 October 1499. The new bridge, opened in 1512, was made of dimension stone, paved with stone, and lined with sixty-eight houses and shops.[54] On 15 July 1533, King Francis I laid the foundation stone for the first Hôtel de Ville, the city hall of Paris. It was designed by his favourite Italian architect, Domenico da Cortona, who also designed the Château de Chambord in the Loire Valley for the king. The Hôtel de Ville was not finished until 1628.[55] Cortona also designed the first Renaissance church in Paris, the church of Saint-Eustache (1532) by covering a Gothic structure with flamboyant Renaissance detail and decoration. The first Renaissance house in Paris was the Hôtel Carnavalet, begun in 1545. It was modelled after the Grand Ferrare, a mansion in Fontainebleau designed by Italian architect Sebastiano Serlio. It is now the Carnavalet Museum.[56]

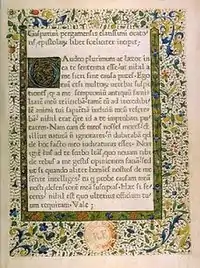

In 1534, Francis I became the first French king to make the Louvre his residence; he demolished the massive central tower to create an open courtyard. Near the end of his reign, Francis decided to build a new wing with a Renaissance façade in place of one wing built by King Philip II. The new wing was designed by Pierre Lescot, and it became a model for other Renaissance façades in France. Francis also reinforced the position of Paris as a center of learning and scholarship. In 1500, there were seventy-five printing houses in Paris, second only to Venice, and later in the 16th century, Paris brought out more books than any other European city. In 1530, Francis created a new faculty at the University of Paris with the mission of teaching Hebrew, Greek and mathematics. It became the Collège de France.[57]

Francis I died in 1547, and his son, Henry II, continued to decorate Paris in the French Renaissance style: the finest Renaissance fountain in the city, the Fontaine des Innocents, was built to celebrate Henry's official entrance into Paris in 1549. Henry II also added a new wing to the Louvre, the Pavillon du Roi, to the south along the Seine. The bedroom of the king was on the first floor of this new wing. He also built a magnificent hall for festivities and ceremonies, the Salle des Cariatides, in the Lescot Wing.[58]

Henry II died 10 July 1559 from wounds suffered while jousting at his residence at the Hôtel des Tournelles. His widow, Catherine de' Medici, had the old residence demolished in 1563, and between 1564 and 1572 constructed a new royal residence, the Tuileries Palace perpendicular to the Seine, just outside the Charles V wall of the city. To the west of the palace, she created a large Italian-style garden, the Jardin des Tuileries.

An ominous gulf was growing within Paris between the followers of the established Catholic church and those of Protestant Calvinism and Renaissance humanism. The Sorbonne and University of Paris, the major fortresses of Catholic orthodoxy, forcefully attacked the Protestant and humanist doctrines, and the scholar Étienne Dolet was burned at the stake, along with his books, on the Place Maubert in 1532 on the orders of the theology faculty of the Sorbonne; but the new doctrines continued to grow in popularity, particularly among the French upper classes. Beginning in 1562, repression and massacres of Protestants in Paris alternated with periods of tolerance and calm, during what became known as the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598). Paris was a stronghold of the Catholic League.[57][59][60][61]

On the night of 23–24 August 1572, while many prominent Protestants from all over France were in Paris on the occasion of the marriage of Henry of Navarre—the future King Henry IV—to Margaret of Valois, sister of Charles IX, the royal council decided to assassinate the leaders of the Protestants. The targeted killings quickly turned into a general slaughter of Protestants by Catholic mobs, known as St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, and it continued through August and September, spreading from Paris to the rest of the country. About three thousand Protestants were massacred in Paris and five to ten thousand elsewhere in France.[57][59][62][61]

King Henry III attempted to find a peaceful solution to the religious conflicts, but the Duke of Guise and his followers in the capital forced him to flee on 12 May 1588, the so-called Day of the Barricades. On 1 August 1589, Henry III was assassinated in the Château de Saint-Cloud by a Dominican friar, Jacques Clément. With the death of Henry III, the Valois line came to an end. Paris, along with the other towns of the Catholic League, held out until 1594 against Henry IV, who had succeeded Henry III.

After a victory over the Holy Union at the Battle of Ivry on 14 March 1590, Henry IV proceeded to lay siege to Paris. The siege was long and unsuccessful. Henry IV agreed to convert to Catholicism. On 14 March 1594, Henry IV entered Paris, after having been crowned King of France at the Cathedral of Chartres on 27 February 1594.

A faculty meeting at the University of Paris in the 16th century.

A faculty meeting at the University of Paris in the 16th century. Saint-Eustache (1532), the first Renaissance church in Paris

Saint-Eustache (1532), the first Renaissance church in Paris The Lescot wing of the Louvre, rebuilt by Francois I beginning in 1546 in the new French Renaissance style.

The Lescot wing of the Louvre, rebuilt by Francois I beginning in 1546 in the new French Renaissance style..JPG.webp) A handful of 16th–17th century houses can still be found in Paris. These houses are at 11 and 13 rue François-Miron in Le Marais.

A handful of 16th–17th century houses can still be found in Paris. These houses are at 11 and 13 rue François-Miron in Le Marais.

17th century

Paris suffered greatly during the wars of religion of the 16th century; a third of the Parisians fled, many houses were destroyed, and the grand projects of the Louvre, the Hôtel de Ville, and the Tuileries Palace were unfinished. Henry IV took away the independence of the city government and ruled Paris directly through royal officers. He relaunched the building projects and built a new wing of the Louvre along the Seine, the galerie du bord de l'eau, which connected the old Louvre with the new Tuileries Palace. The project of making the Louvre into a single great palace continued for the next three hundred years.[63]

Henry IV's building projects for Paris were managed by a Protestant, the Duke of Sully, his forceful superintendent of buildings and minister of finances who was named Grand Master of Artillery in 1599. Henry IV recommenced the construction of the Pont Neuf, started by Henry III in 1578, but left unfinished during the wars of religion. It was finished between 1600 and 1607. It was the first Paris bridge built without houses. Instead, it was uncovered and equipped with sidewalks. Near the bridge, he built "La Samaritaine" (1602–1608), a large pumping station which provided drinking water as well as water for the gardens of the Louvre and the Tuileries.[64]

To the south of the vacant site of the former royal residence of Henry II, the Hôtel des Tournelles, he built an elegant new residential square surrounded by brick houses and an arcade. It was built between 1605 and 1612 and named the "Place Royale". In 1800, it was renamed the Place des Vosges. In 1607, Henry began work on a new residential triangle, the Place Dauphine, lined by thirty-two brick and stone houses, at the western end of the Île de la Cité. It was his final project for the city of Paris. Henri IV was assassinated on 14 May 1610 by François Ravaillac, a Catholic fanatic. Four years later, a bronze equestrian statue of the murdered king was erected on the Pont Neuf that faced the Place Dauphine.[64]

Henry IV's widow Marie de Medicis decided to build her own residence, the Luxembourg Palace (1615–1630), modelled after the Pitti Palace in her native Florence. In the Italian gardens of her palace, she commissioned a Florentine fountain-maker, Tommaso Francini, to create the Medici Fountain. Water was scarce in the Left Bank, one reason it had grown more slowly than the Right Bank. To provide water for her gardens and fountains, Marie de Medicis had the old Roman aqueduct from Rungis reconstructed. In 1616, she also created the Cours-la-Reine west of the Tuileries Gardens along the Seine. It was another reminder of Florence, a long promenade lined with eighteen hundred elm trees.[65]

Louis XIII continued the Louvre project begun by Henri IV by creating the harmonious cour carrée, or square courtyard, in the heart of the Louvre. His chief minister, the Cardinal de Richelieu, added another important building in the centre of Paris. In 1624, he started construction of a grand new residence for himself, the "Palais-Cardinal", now known as the Palais-Royal. He began by buying several large mansions located on the Rue Saint-Honoré (next to the then still-existing Wall of Charles V), the (first) Hôtel de Rambouillet and adjacent Hôtel d'Armagnac, then expanding it with an enormous garden (three times larger than the present garden), with a fountain in the centre and long rows of trees on either side.[66]

In the first part of the 17th century, Richelieu helped introduce a new religious architectural style into Paris that was inspired by the famous churches in Rome, particularly the Church of the Gesù and the Basilica of Saint Peter. The first façade built in the Jesuit style was that of the church of Saint-Gervais (1616). The first church entirely built in the new style was Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis, on the Rue Saint-Antoine in Le Marais, between 1627–1647. It was not entirely in the Jesuit style, since the architects could not resist loading it with ornament, but it was appreciated by Kings Louis XIII and Louis XIV; the hearts of both kings were interred there.[67]

The dome of Saint Peter's in Rome inspired the dome of the chapel of the Sorbonne (1635–1642) commissioned by Cardinal Richelieu, who was the proviseur, or head of the college. The chapel became his final resting place. The plan was taken from another Roman church, San Carlo ai Catinari. The new style, sometimes called Flamboyant Gothic or French baroque, appeared in many other new churches, including Notre-Dame de Bonne-Nouvelle (1624), Notre-Dame-des-Victoires (1629), Saint-Sulpice (1646), and Saint-Roch (1653).[63]

The largest project in the new style was Val-de-Grâce, built by Anne of Austria, the widow of Louis XIII. Modeled after the Escorial in Spain, it combined a convent, a church, and royal apartments for the widowed queen. One of the architects of Val-de-Grâce and several of the other new churches was François Mansart, most famous for the sloping roof that became the signature feature of the buildings of the 17th century.[63]

During the first half of the 17th century, the population of Paris nearly doubled, reaching 400,000 at the end of the reign of Louis XIII in 1643.[68] To facilitate communication between the Right Bank and Left Bank, Louis XIII built five new bridges over the Seine, doubling the existing number. The nobility, government officials and the wealthy built elegant hôtels particuliers, or town residences, on the Right Bank in the new Faubourg Saint-Honoré, the Faubourg Saint-Jacques, and in the Marais near the Place des Vosges. The new residences featured two new and original specialized rooms: the dining-room and the salon. One good example in its original form, the Hôtel de Sully (1625–1630), between the Place des Vosges and Rue Saint-Antoine, can be seen today.[69]

The old ferryboat between the Louvre and the Rue de Bac on the Left Bank (bac designates a flat boat ferry) was replaced by a wooden and then a stone bridge, the Pont Royal, finished by Louis XIV. Near the end of new bridge on the Left Bank, a new fashionable neighborhood, the Faubourg Saint-Germain, soon appeared. Under Louis XIII, two small islands in the Seine, the Île Notre-Dame and the Île-aux-vaches, which had been used for grazing cattle and storing firewood, were combined to form the Île Saint-Louis, which became the site of the splendid hôtels particuliers of Parisian financiers.[69]

Under Louis XIII, Paris solidified its reputation as the cultural capital of Europe. Beginning in 1609, the Louvre Galerie was created, where painters, sculptors, and artisans lived and established their workshops. The Académie Française, modelled after the academies of Italian Renaissance princes, was created in 1635 by Cardinal Richelieu. The Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, later the Academy of Fine Arts, was founded in 1648. The first botanical garden in France, the Jardin du Roy, (renamed Jardin des plantes in 1793 after the monarchy was abolished during the French Revolution), was founded in 1633, both as a conservatory of medicinal plants and for botanical research. It was the first public garden in Paris. The first permanent theatre in Paris was created by Cardinal Richelieu in 1635 within his Palais-Cardinal.[70]

Richelieu died in 1642, and Louis XIII in 1643. At the death of his father, Louis XIV was only five years old, and his mother Anne of Austria became regent. Richelieu's successor, Cardinal Mazarin, tried to impose a new tax upon the Parlement of Paris, which consisted of a group of prominent nobles of the city. When they refused to pay, Mazarin had the leaders arrested. This marked the beginning a long uprising, known as the Fronde, that pitted the Parisian nobility against royal authority. It lasted from 1648 to 1653.[71]

At times, the young Louis XIV was held under virtual house arrest in the Palais-Royal. He and his mother were forced to flee the city twice, in 1649 and 1651, to the royal château at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, until the army could retake control of Paris. As a result of the Fronde, Louis XIV had a profound lifelong distrust of Paris. He moved his Paris residence from the Palais-Royal to the more secure Louvre and then, in 1671, he moved the royal residence out of the city to Versailles and came into Paris as seldom as possible.[71]

Despite the distrust of the king, Paris continued to grow and prosper, reaching a population of between 400,000 and 500,000. The king named Jean-Baptiste Colbert as his new Superintendent of Buildings, and Colbert began an ambitious building programme to make Paris the successor to ancient Rome. To make his intention clear, Louis XIV organised a festival in the carrousel of the Tuileries in January 1661, in which he appeared, on horseback, in the costume of a Roman Emperor, followed by the nobility of Paris. Louis XIV completed the Cour carrée of the Louvre and built a majestic row of columns along its east façade (1670). Inside the Louvre, his architect Louis Le Vau and his decorator Charles Le Brun created the Gallery of Apollo, the ceiling of which featured an allegoric figure of the young king steering the chariot of the sun across the sky. He enlarged the Tuileries Palace with a new north pavilion, and had André Le Nôtre, the royal gardener, remodel the gardens of the Tuileries.

Across the Seine from the Louvre, Louis XIV built the Collège des Quatre-Nations (College of the Four Nations) (1662–1672), an ensemble of four baroque palaces and a domed church, to house students coming to Paris from four provinces recently attached to France (today it is the Institut de France). He built a new hospital for Paris, the Salpêtrière, and, for wounded soldiers, a new hospital complex with two churches: Les Invalides (1674). In the centre of Paris, he constructed two monumental new squares, the Place des Victoires (1689) and the Place Vendôme (1698). Louis XIV declared that Paris was secure against any attack and no longer needed its walls. He demolished the main city walls, creating the space which eventually became the Grands Boulevards. To celebrate the destruction of the old walls, he built two small arches of triumph, the Porte Saint-Denis (1672) and the Porte Saint-Martin (1676).

The cultural life of the city also flourished; the city's future most famous theater, the Comédie Française, was created in 1681 on a former tennis court on the Rue Fossés Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The city's first café-restaurant, the Café Procope, was opened in 1686 by the Italian Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli.[72]

For the poor of Paris, life was very different. They were crowded into tall, narrow, five- or six-story high buildings that lined the winding streets on the Île de la Cité and other medieval quarters of the city. Crime in the dark streets was a serious problem. Metal lanterns were hung in the streets, and Colbert increased to four hundred the number of archers who acted as night watchmen. Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie was appointed the first lieutenant-general of police of Paris in 1667, a position he held for thirty years; his successors reported directly to the king.[73]

18th century

Louis XIV died on 1 September 1715. His nephew, Philippe d'Orléans, the regent for the five-year-old King Louis XV, moved the royal residence and government back to Paris, where it remained for seven years. The king lived in the Tuileries Palace, while the regent lived in his family's luxurious Parisian residence, the Palais-Royal (the former Palais-Cardinal of Cardinal Richelieu). The regent devoted his attention to theater, opera, costume balls, and the courtesans of Paris.[74]

He made one important contribution to Paris intellectual life. In 1719, he moved the Royal library to the Hôtel de Nevers near the Palais-Royal, where it eventually became part of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (National Library of France). On 15 June 1722, distrustful of the turbulence in Paris, the regent moved the court back to Versailles. Afterwards, Louis XV visited the city only on special occasions.[75]

One of the major building projects in Paris of Louis XV and his successor, Louis XVI, was the new church of Sainte Geneviève on top of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève on the Left Bank, the future Panthéon. The plans were approved by the king in 1757 and work continued until the French Revolution. Louis XV also built an elegant new military school, the École Militaire (1773), a new medical school, the École de Chirurgie (1775), and a new mint, the Hôtel des Monnaies (1768), all on the Left Bank.[76]

Expansion

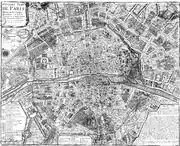

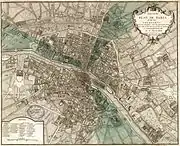

Under Louis XV, the city expanded westward. A new boulevard, the Champs-Élysées, was laid out from the Tuileries Garden to the Rond-Point on the Butte (now the Place de l'Étoile) and then to the Seine to create a straight line of avenues and monuments known as Paris historical axis. At the beginning of the boulevard, between the Cours-la-Reine and the Tuileries gardens, a large square was created between 1766 and 1775, with an equestrian statue of Louis XV in the center. It was first called "Place Louis XV", then the "Place de la Révolution" after 10 August 1792, and finally the Place de la Concorde in 1795 at the time of the Directoire.[77]

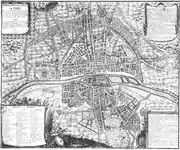

Between 1640 and 1789, Paris grew in population from 400,000 to 600,000. It was no longer the largest city in Europe; London passed it in population in about 1700, but it was still growing at a rapid rate, due largely to migration from the Paris basin and from the north and east of France. The center of the city became more and more crowded; building lots became smaller and buildings taller, up to four, five and even six stories. In 1784, the height of buildings was finally limited to nine toises, or about eighteen meters.[78]

Age of Enlightenment

In the 18th century, Paris was the center of an explosion of philosophic and scientific activity known as the Age of Enlightenment. Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert published their Encyclopédie in 1751–52. It provided intellectuals across Europe with a high quality survey of human knowledge. The Montgolfier brothers launched the first manned flight in a hot-air balloon on 21 November 1783, from the Château de la Muette, near the Bois de Boulogne. Paris was the financial capital of France and continental Europe, the primary European center of book publishing, fashion, and the manufacture of fine furniture and luxury goods.[79] Parisian bankers funded new inventions, theatres, gardens, and works of art. The successful Parisian playwright Pierre de Beaumarchais, the author of The Barber of Seville, helped fund the American Revolution.

The first café in Paris had been opened in 1672, and by the 1720s there were around 400 cafés in the city. They became meeting places for the city's writers and scholars. The Café Procope was frequented by Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Diderot and d’Alembert.[80] They became important centres for exchanging news, rumors and ideas, often more reliable than the newspapers of the day.[81]

By 1763, the Faubourg Saint-Germain had replaced Le Marais as the most fashionable residential neighborhood for the aristocracy and the wealthy, who built magnificent private mansions, most of which later became government residences or institutions: the Hôtel d'Évreux (1718–1720) became the Élysée Palace, the residence of the presidents of the French Republic; the Hôtel Matignon, the residence of the prime minister; the Palais Bourbon, the seat of the National Assembly; the Hôtel Salm, the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur; and the Hôtel de Biron eventually became the Rodin Museum.[82]

Architecture

The predominant architectural style in Paris from the mid-17th century until the regime of Louis Philippe was neo-classicism, based on the model of Greco-Roman architecture; the most classical example was the new church of La Madeleine, whose construction began in 1764. It was so widely used that it invited criticism. Just before the Revolution, the journalist Louis-Sébastien Mercier commented as follows: "How monotonous is the genius of our architects! How they live on copies, on eternal repetition! They don't know how to make the smallest building without columns... They all more or less resemble temples."[83]

Social problems and taxation

Historian Daniel Roche estimated that in 1700 there were between 150,000 and 200,000 indigent persons in Paris, or about a third of the population. The number grew in times of economic hardship. This included only those who were officially recognized and assisted by the churches and the city.[84]

Paris in the first half of the 18th century had many beautiful buildings, but many observers did not consider it a beautiful city. The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau described his disappointment when he first arrived in Paris from Lyon in 1742:

- "I expected a city as beautiful as it was grand, of an imposing appearance, where you saw only superb streets, and palaces of marble and gold. Instead, when I entered by the Faubourg Saint-Marceau, I saw only narrow, dirty and foul-smelling streets, and villainous black houses, with an air of unhealthiness; beggars, poverty; wagons-drivers, menders of old garments; and vendors of tea and old hats."[85]

In 1749, in his Embellissements de Paris, Voltaire observed this: "We blush with shame to see the public markets, set up in narrow streets, displaying their filth, spreading infection, and causing continual disorders....Immense neighbourhoods need public places. The centre of the city is dark, cramped, hideous, something from the time of the most shameful barbarism."[86]

The main working-class neighbourhood was the old Faubourg Saint-Antoine on the eastern side of the city, a centre for woodwork and furniture-making since the Middle Ages. Many of the artisans' workshops were located there, and it was the home of about ten percent of the population of Paris. The city continued to spread outwards, especially toward the semi-rural west and northwest, where one- and two-story stone and wooden houses were mingled with vegetable gardens, shacks, and workshops.[78]

The city had no mayor or single city government; its police chief reported to the king, the prévôt des marchands de Paris represented the merchants, and the Parlement de Paris, made up of nobles, was largely ceremonial and had little real authority: they struggled to provide the basic necessities to a growing population. For the first time, metal plates or stone were put up to indicate the names of streets, and each building was given a number. Rules for hygiene, safety and traffic circulation were codified by the Lieutenant-General of Police. The first oil lamps were installed on the streets late in the 18th century.[87]

Large steam pumps were built at Gros-Caillaux and Chaillot to distribute water to the neighbourhoods that could afford it. There were still no proper sewers; the river Bièvre served as an open sewer, discharging the sewage into the Seine. The first fire brigades were organised between 1729 and 1801, particularly after a large fire destroyed the opera house of the Palais-Royal in 1781. In the streets of Paris, the chairs in which the aristocrats and rich bourgeois were carried by their servants gradually disappeared and were replaced by horse-drawn carriages, both private and for hire. By 1750, there were more than ten thousand carriages for hire in Paris, the first Paris taxis.[87]

Louis XVI ascended the throne of France in 1774, and his new government in Versailles desperately needed money. The treasury had been drained by the Seven Years' War (1755–63), and the French intervention in the American Revolution would create even more serious financial problems after 1776. In order to raise revenues by charging taxes on merchandise coming into the city, Paris was encircled between 1784 and 1791 by a new wall that stopped merchants who wished to enter Paris. The wall, known as the Wall of the Ferme générale, was twenty-five kilometres long, four to five metres high, and had fifty-six gates at which taxes had to be paid. Portions of the wall can still be seen at the Place Denfert-Rochereau and the Place de la Nation, and one of the toll gates is still standing in the Parc Monceau. The wall and the taxes were highly unpopular, and, along with shortages of bread, fuelled the growing discontent which eventually exploded in the French Revolution.[87]

French Revolution (1789–1799)

In the summer of 1789, Paris became the center stage of the French Revolution and events that changed the history of France and Europe. In 1789, the population of Paris was between 600,000 and 640,000. Then as now, most wealthier Parisians lived in the western part of the city, the merchants in the center, and the workers and artisans in the southern and eastern parts, particularly the Faubourg Saint-Honoré. The population included about one hundred thousand extremely poor and unemployed persons, many of whom had recently moved to Paris to escape hunger in the countryside. Known as the sans-culottes, they made up as much as a third of the population of the eastern neighborhoods and became important actors in the Revolution.[88]

On 11 July 1789, soldiers of the Royal-Allemand regiment attacked a large but peaceful demonstration on the Place Louis XV organized to protest the dismissal by the king of his reformist finance minister Jacques Necker. The reform movement turned quickly into a revolution.[88] On 13 July, a crowd of Parisians occupied the Hôtel de Ville, and the Marquis de Lafayette organized the French National Guard to defend the city. On 14 July, a mob seized the arsenal at the Invalides, acquired thousands of guns, and stormed the Bastille, a prison that was a symbol of royal authority, but at that time held only seven prisoners. 87 revolutionaries were killed in the fighting. The governor of the Bastille, the Marquis de Launay, surrendered and then was killed, his head put on the end of a pike and carried around Paris. The provost of the merchants of Paris, Jacques de Flesselles, was also murdered.[89] The fortress itself was completely demolished by November, and the stones turned into souvenirs.[90]

The first independent Paris Commune, or city council, met in the Hôtel de Ville on 15 July and chose as the first mayor of Paris the astronomer Jean Sylvain Bailly.[91] Louis XVI came to Paris on 17 July, where he was welcomed by the new mayor and wore a tricolor cockade on his hat: red and blue, the colors of Paris, and white, the royal color.[92]

On 5 October 1789, a large crowd of Parisians marched to Versailles and, the following day, brought the royal family and government back to Paris, virtually as prisoners. The new government of France, the National Assembly, began to meet in the Salle du Manège near the Tuileries Palace on the outskirts of the Tuileries garden.[93]

On 21 May 1790, the Charter of the City of Paris was adopted, declaring the city independent of royal authority: it was divided into twelve municipalities, (later known as arrondissements), and forty-eight sections. It was governed by a mayor, sixteen administrators and thirty-two city council members. Bailly was formally elected mayor by the Parisians on 2 August 1790.[94]

A solemn ceremony, the Fête de la Fédération, was held on the Champ de Mars on 14 July 1790. The units of the National Guard, led by Lafayette, took an oath to defend "The Nation, the Law and the King" and swore to uphold the Constitution approved by the king.[93]

Louis XVI and his family fled Paris on 21 June 1791, but were captured in Varennes and brought back to Paris on 25 June. Hostility grew within Paris between the liberal aristocrats and merchants, who wanted a constitutional monarchy, and the more radical sans-culottes from the working-class and poor neighbourhoods, who wanted a republic and the abolition of the Ancien Régime, including the privileged classes: the aristocracy and the Church. Aristocrats continued to leave Paris for safety in the countryside or abroad. On 17 July 1791, the National Guard fired upon a gathering of petitioners on the Champs de Mars, killing dozens and widening the gulf between the more moderate and more radical revolutionaries.

Revolutionary life was centered around political clubs. The Jacobins had their headquarters in the former Dominican friary, the Couvent des Jacobins de la rue Saint-Honoré, while its most influential member, Robespierre, lived at 366 (now 398) Rue Saint-Honoré. The Left Bank, near the Odéon Theater, was the home of the club of Cordeliers, of which the principal members were Jean-Paul Marat, Georges Danton, Camille Desmoulins, and of the printers who published the newspapers and pamphlets that inflamed public opinion.

In April 1792, Austria declared war on France, and in June 1792, the Duke of Brunswick, commander of the army of the King of Prussia, threatened to destroy Paris unless the Parisians accepted the authority of their king.[95] In response to the threat from the Prussians, on 10 August the leaders of the sans-culottes deposed the Paris city government and established their own government, the Insurrectionary Commune, in the Hôtel-de-Ville. Upon learning that a mob of sans-culottes was approaching the Tuileries Palace, the royal family took refuge at the nearby Assembly. In the attack of the Tuileries Palace, the mob killed the last defenders of the king, his Swiss Guards, then ransacked the palace. Threatened by the sans-culottes, the Assembly "suspended" the power of the king and, on 11 August, declared that France would be governed by a National Convention. On 13 August, Louis XVI and his family were imprisoned in the Temple fortress. On 21 September, at its first meeting, the Convention abolished the monarchy, and the next day declared France to be a republic. The Convention moved its meeting place to a large hall, a former theatre, the Salle des Machines within the Tuileries Palace. The Committee of Public Safety, charged with hunting down the enemies of the Revolution, established its headquarters in the Pavillon de Flore, the south pavilion of the Tuileries, while the Tribunal, the revolutionary court, set up its courtroom within the old Palais de la Cité, the medieval royal residence on the Île-de-la-Cité, the site of today's Palais de Justice.[96]

The new government imposed a Reign of Terror upon France. From 2 to 6 September 1792, bands of sans-culottes broke into the prisons and murdered refractory priests, aristocrats and common criminals. On 21 January 1793, Louis XVI was guillotined on the Place de la Révolution. Marie Antoinette was executed on the same square on 16 October 1793. Bailly, the first Mayor of Paris, was guillotined the following November at the Champ de Mars. During the Reign of Terror, 16,594 persons were tried by the revolutionary tribune and executed by the guillotine.[97] Tens of thousands of others associated with the Ancien Régime were arrested and imprisoned. Property of the aristocracy and the Church was confiscated and declared Biens nationaux (national property). The churches were closed.

The French Republican Calendar, a new non-Christian calendar, was created, with the year 1792 becoming "Year One": 27 July 1794 was "9 Thermidor of the year II". Many street names were changed, and the revolutionary slogan, "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity", was engraved on the façades of government buildings. New forms of address were required:Monsieur and Madame were replaced by Citoyen ("citizen") and Citoyenne ("citizeness"), and the formal vous ("you") was replaced by the more proletarian tu.[98]

On order of the Legislative Assembly (in a decree of August 1792),[99] the sans-culottes knocked down the spire of Notre Dame Cathedral in 1792. A decree of 1 August 1793 was issued to commemorate the first anniversary of the fall of the monarchy by destroying the tombs at the royal necropolis of Saint-Denis.[100][101][102] On order of the Commune of Paris on 23 October 1793,[103] the sans-culottes attacked the façade of the cathedral, destroying the figures of the kings of the Old Testament, having been told they were statues of the kings of France. A number of prominent historic buildings, including the enclosure of the Temple, the Abbey of Montmartre, and most of the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, were nationalized and demolished. Many churches were sold as public property and were demolished for their stone and other construction material. Henri Grégoire, a priest and elected member of the Convention, invented a new word, "vandalism", to describe the destruction of property ordered by the government during the Revolution.[98]

A succession of revolutionary factions ruled Paris: on 1 June 1793, the Montagnards seized power from the Girondins, then were replaced by Georges Danton and his followers; in 1794, they were overthrown and guillotined by a new government led by Maximillien Robespierre. On 27 July 1794, Robespierre himself was arrested by a coalition of Montagnards and moderates. The following day, he was guillotined in the company of twenty-one of his political allies. His execution marked the end of the Reign of Terror. The executions then ceased and the prisons gradually emptied.[104]

A small group of scholars and historians collected statues and paintings from the demolished churches, and made a storeroom of the old Couvent des Petits-Augustins, in order to preserve them. The paintings went to the Louvre, where the Central Museum of the Arts was opened at the end of 1793. In October 1795, the collection at the Petits-Augustins became officially the Museum of French Monuments.[104]

A new government, the Directory, took the place of the Convention. It moved its headquarters to the Luxembourg Palace and limited the autonomy of Paris. When the authority of the Directory was challenged by a royalist uprising on 13 Vendémiaire, Year IV (5 October 1795), the Directory called upon a young general, Napoléon Bonaparte, for help. Bonaparte used cannon and grapeshot to clear the streets of demonstrators. On 18 Brumaire, Year VIII (9 November 1799), he organised a coup d'état that overthrew the Directory and replaced it by the Consulate with Bonaparte as First Consul. This event marked the end of the French Revolution and opened the way to the First French Empire.[105]

The population of Paris had dropped to 570,000 by 1797,[106] but building still continued. A new bridge over the Seine, the modern Pont de la Concorde, which had been started under Louis XVI, was completed in 1792. Other landmarks were converted to new purposes: the Panthéon was transformed from a church into a mausoleum for notable Frenchmen, the Louvre became a museum, and the Palais-Bourbon, a former residence of the royal family, became the home of the National Assembly. The two first covered commercial streets in Paris, the Passage du Caire and the Passage des Panoramas, were opened in 1799.

Under Napoleon I (1800–1815)

First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte moved into the Tuileries Palace on 19 February 1800 and immediately began to re-establish calm and order after the years of uncertainty and terror of the Revolution. He made peace with the Catholic church by signing the Concordat of 1801 with Pope Pius VII; masses were held again in all churches in Paris (and in the whole of France), priests were allowed to wear ecclesiastical clothing again, and churches were permitted to ring their bells.[107] To re-establish order in the unruly city, he abolished the elected position of the Mayor of Paris, and replaced it with a Prefect of the Seine appointed by him on 17 February 1800. The first prefect, Louis Nicolas Dubois, was appointed on 8 March 1800 and held his position until 1810. Each of the twelve arrondissements had its own mayor, but their power was limited to enforcing the decrees of Napoleon's ministers.[108]

After he crowned himself Emperor on 2 December 1804, Napoleon began a series of projects to make Paris into an imperial capital to rival ancient Rome. He began construction of the Rue de Rivoli, from the Place de la Concorde to the Place des Pyramides. The old convent of the Capucines was demolished, and he built a new street that connected Place Vendôme to the Grands Boulevards. The street was called the "Rue Napoléon", later renamed the Rue de la Paix.[109]

In 1802, Napoleon built a revolutionary iron bridge, the Pont des Arts, across the Seine. It was decorated with two greenhouses of exotic plants and rows of orange trees. Passage across the bridge cost one sou.[109] He gave the names of his victories to two new bridges, the Pont d'Austerlitz (1802) and the Pont d'Iéna (1807)[110]

In 1806, in imitation of Ancient Rome, Napoleon ordered the construction of a series of monuments dedicated to the military glory of France. The first and largest was the Arc de Triomphe, built at the western edge of the city at the Barrière d'Étoile, and finished only in July 1836 during the July Monarchy. He ordered the building of the smaller Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel (1806–1808), copied from the arch of Arch of Septimius Severus and Constantine in Rome, in line with the center of the Tuileries Palace. It was crowned with a team of bronze horses that he took from the façade of St Mark's Basilica in Venice. The Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel is the easternmost monument of the historical axis of Paris. Napoleon's soldiers celebrated his victories with grand parades around the Carrousel. He also commissioned the building of the Vendôme Column (1806–10), copied from Trajan's Column in Rome, made of the iron of cannon captured from the Russians and Austrians in 1805. At the end of the Rue de la Concorde (given again its former name of Rue Royale on 27 April 1814), he took the foundations of an unfinished church, the Madeleine, which had been started in 1763, and transformed it into the Temple de la Gloire, a military shrine to display the statues of France's most famous generals.[111]

Napoleon also looked after the infrastructure of the city, which had been neglected for years. In 1802, he began construction of the Canal de l'Ourcq to bring fresh water to the city and built the Bassin de la Villette to serve as a reservoir. To distribute the fresh water to the Parisians, he built a series of monumental fountains, the largest of which was the Fontaine du Palmier, on the Place du Châtelet. He also began construction of the Canal Saint-Martin to further river transportation within the city.[111]

Napoleon's last public project, begun in 1810, was the construction of the Elephant of the Bastille, a fountain in the shape of an colossal bronze elephant, twenty-four meters high, which was intended for the center of the Place de la Bastille, but he did not have time to finish it. An enormous plaster mockup of the elephant stood in the square for many years after the emperor's final defeat and exile. In 1811, Napoleon decreed the building of an immense palace on the Chaillot Hill across the river from the Champ de Mars. It was intended to eclipse every palace in Europe in size and luxury, but only the foundations had been laid before Napoleon's fall from power brought an end to the project.[112]

Restoration (1815–1830)

Following the downfall of Napoleon after the defeat of Waterloo on 18 June 1815, 300,000 soldiers of the Seventh Coalition armies from England, Austria, Russia and Prussia occupied Paris and remained until December 1815. Louis XVIII returned to the city and moved into the former apartments of Napoleon at the Tuileries Palace.[113] The Pont de la Concorde was renamed "Pont Louis XVI", a new statue of Henry IV was put back on the empty pedestal on the Pont Neuf, and the white flag of the Bourbons flew from the top of the column in Place Vendôme.[114]

The aristocrats who had emigrated returned to their town houses in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, and the cultural life of the city quickly resumed, though on a less extravagant scale. A new opera house was constructed on Rue Le Peletier. The Louvre was expanded in 1827 with nine new galleries that put on display the antiquities collected during Napoleon's conquest of Egypt.

Work continued on the Arc de Triomphe, and the new churches in the neoclassical style were constructed to replace those destroyed during the Revolution: Saint-Pierre-du-Gros-Caillou (1822–1830); Notre-Dame-de-Lorette (1823–1836); Notre-Dame de Bonne-Nouvelle (1828–1830); Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (1824–1844) and Saint-Denys-du-Saint-Sacrement (1826–1835). The Temple of Glory (1807) created by Napoleon to celebrate military heroes was turned back into a church, the church of La Madeleine. King Louis XVIII also built the Chapelle expiatoire, a chapel devoted to Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, on the site of the small Madeleine cemetery, where their remains (now in the Basilica of Saint-Denis) were buried following their execution.[115]

Paris grew quickly, and passed 800,000 in 1830.[116] Between 1828 and 1860, the city built a horse-drawn omnibus system that was the world's first mass public transit system. It greatly speeded the movement of people inside the city and became a model for other cities.[117] The old Paris street names, carved into stone on walls, were replaced by royal blue metal plates with the street names in white letters, the model still in use today. Fashionable new neighborhoods were built on the right bank around the church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, the church of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, and the Place de l’Europe. The "New Athens" neighbourhood became, during the Restoration and the July Monarchy, the home of artists and writers: the actor François-Joseph Talma lived at number 9 Rue de la Tour-des-Dames; the painter Eugène Delacroix lived at 54 Rue Notre-Dame de-Lorette; the novelist George Sand lived in the Square d'Orléans. The latter was a private community that opened at 80 Rue Taitbout, which had forty-six apartments and three artists' studios. Sand lived on the first floor of number 5, while Frédéric Chopin lived for a time on the ground floor of number 9.[118]

Louis XVIII was succeeded by his brother Charles X in 1824, but new the government became increasingly unpopular with both the upper classes and the general population of Paris. The play Hernani (1830) by the twenty-eight-year-old Victor Hugo, caused disturbances and fights in the theater audience because of its calls for freedom of expression. On 26 July, Charles X signed decrees limiting freedom of the press and dissolving the Parliament, provoking demonstrations which turned into riots which turned into a general uprising. After three days, known as the ‘’Trois Glorieuses’’, the army joined the demonstrators. Charles X, his family and the court left the Château de Saint-Cloud, and, on 31 July, the Marquis de Lafayette and the new constitutional monarch Louis-Philippe raised the tricolor flag again before cheering crowds at the Hôtel de Ville.[116]

Under Louis-Philippe (1830–1848)

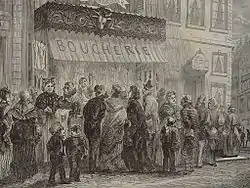

The Paris of King Louis-Philippe was the city described in the novels of Honoré de Balzac and Victor Hugo. The population of Paris increased from 785,000 in 1831 to 1,053,000 in 1848, as the city grew to the north and west, but the poorest neighborhoods in the center became even more densely crowded.[119]

The heart the city, around the Île de la Cité, was a maze of narrow, winding streets and crumbling buildings from earlier centuries; it was picturesque, but dark, crowded, unhealthy and dangerous. Water was distributed by porters carrying buckets from a pole on their shoulders, and the sewers emptied directly into the Seine. A cholera outbreak in 1832 killed twenty thousand people. The Comte de Rambuteau, the Prefect of the Seine for fifteen years under Louis-Philippe, made tentative efforts to improve the center of the city: he paved the quays of the Seine with stone paths and planted trees along the river. He built a new street (now the Rue Rambuteau) to connect the Le Marais district with the markets and began construction of Les Halles, the famous central market of Paris, which was finished by Napoleon III.[120]

Louis-Philippe lived in the ancestral Orléans family residence of the House of Orléans, the Palais-Royal, until 1832, before moving to the Tuileries Palace. His chief contribution to the monuments of Paris was the completion of the Place de la Concorde in 1836: the huge square was decorated with two fountains, one representing fluvial commerce, Fontaine des Fleuves, and the other maritime commerce, Fontaine des Mers, and eight statues of women representing eight great cities of France: Brest and Rouen (by Jean-Pierre Cortot), Lyon and Marseille (by Pierre Petitot), Bordeaux and Nantes (by Louis-Denis Caillouette), Lille and Strasbourg (by James Pradier). The statue of Strasbourg was a likeness of Juliette Drouet, the mistress of Victor Hugo. The Place de la Concorde was further embellished on 25 October 1836 by the placement of the Luxor Obelisk, weighing two hundred fifty tons, which was carried to France from Egypt on a specially-built ship. In the same year, at the westernmost end of the Champs-Élysées, Louis-Philippe completed and dedicated the Arc de Triomphe, which had been begun by Napoleon.[120]

The ashes of Napoleon were returned to Paris from Saint Helena in a solemn ceremony on 15 December 1840 at the Invalides. Louis-Philippe also placed the statue of Napoleon atop the column in the Place Vendôme. In 1840, he completed a column in the Place de la Bastille dedicated to the July 1830 revolution that had brought him to power. He also began the restoration of the churches of Paris damaged during the French Revolution, a project carried out by the architectural historian Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, beginning with the church of the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Between 1837 and 1841, he built a new Hôtel de Ville with an interior salon decorated by Eugène Delacroix.[121]

The first railway stations in Paris were built under Louis-Philippe. Each belonged to a different company. They were not connected to each other and were outside the center of the city. The first, called the Embarcadère de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, was opened on 24 August 1837 on the Place de l'Europe. An early version of the Gare Saint-Lazare was begun in 1842, and the first lines Paris-Orléans and Paris-Rouen were inaugurated on 1 and 2 May 1843.[122]