Falklands War

The Falklands War (Spanish: Guerra de las Malvinas) was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and its territorial dependency, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

| Falklands War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

From top right and in clockwise direction: HMS Hermes and HMS Broadsword of the British Task Force; Argentinian ARA General Belgrano sinking; Argentinian Army POWs in Stanley; British HMS Antelope after being hit (later sank); two Super Étendards of the Argentinian Navy; Argentinian forces at Port Stanley, 2 April 1982 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

The conflict began on 2 April, when Argentina invaded and occupied the Falkland Islands, followed by the invasion of South Georgia the next day. On 5 April, the British government dispatched a naval task force to engage the Argentine Navy and Air Force before making an amphibious assault on the islands. The conflict lasted 74 days and ended with an Argentine surrender on 14 June, returning the islands to British control. In total, 649 Argentine military personnel, 255 British military personnel, and three Falkland Islanders died during the hostilities.

The conflict was a major episode in the protracted dispute over the territories' sovereignty. Argentina asserted (and maintains) that the islands are Argentine territory,[4] and the Argentine government thus characterised its military action as the reclamation of its own territory. The British government regarded the action as an invasion of a territory that had been a Crown colony since 1841. Falkland Islanders, who have inhabited the islands since the early 19th century, are predominantly descendants of British settlers, and strongly favour British sovereignty. Neither state officially declared war, although both governments declared the islands a war zone.

The conflict has had a strong effect in both countries and has been the subject of various books, articles, films, and songs. Patriotic sentiment ran high in Argentina, but the unfavourable outcome prompted large protests against the ruling military government, hastening its downfall and the democratisation of the country. In the United Kingdom, the Conservative government, bolstered by the successful outcome, was re-elected with an increased majority the following year. The cultural and political effect of the conflict has been less in the UK than in Argentina, where it has remained a common topic for discussion.[5]

Diplomatic relations between the United Kingdom and Argentina were restored in 1989 following a meeting in Madrid, at which the two governments issued a joint statement.[6] No change in either country's position regarding the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands was made explicit. In 1994, Argentina adopted a new constitution,[7] which declared the Falkland Islands as part of one of its provinces by law.[8] However, the islands continue to operate as a self-governing British Overseas Territory.[9]

Prelude

Failed diplomacy

In 1965, the United Nations called upon Argentina and the United Kingdom to reach a settlement of the sovereignty dispute. The UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) regarded the islands as a nuisance and barrier to UK trade in South America. Therefore, while confident of British sovereignty, the FCO was prepared to cede the islands to Argentina. When news of a proposed transfer broke in 1968, elements sympathetic with the plight of the islanders were able to organise an effective parliamentary lobby to frustrate the FCO plans. Negotiations continued, but in general failed to make meaningful progress; the islanders steadfastly refused to consider Argentine sovereignty on one side, whilst Argentina would not compromise over sovereignty on the other.[10] The FCO then sought to make the islands dependent on Argentina, hoping this would make the islanders more amenable to Argentine sovereignty. A Communications Agreement signed in 1971 created an airlink and later YPF, the Argentine oil company, was given a monopoly in the islands.

In 1977, British prime minister James Callaghan, in response to heightened tensions in the region and the Argentinian occupation of Southern Thule, secretly sent a force of two frigates and a nuclear-powered submarine, HMS Dreadnought, to the South Atlantic, codenamed Operation Journeyman.[11] It is unclear whether the Argentinians were aware of their presence, but British sources state that they were advised through informal channels. Nevertheless, talks with Argentina on Falklands sovereignty and economic cooperation opened in December of that year, but were inconclusive.[12]

In 1980, a new U.K. Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Nicholas Ridley, went to the Falklands trying to sell the islanders the benefits of a leaseback scheme, which met with strong opposition from the islanders. On returning to London in December 1980, he reported to parliament but was viciously attacked at what was seen as a sellout. (It was unlikely that leaseback could have succeeded since the British had sought a long-term lease of 99 years, whereas Argentina was pressing for a much shorter period of only ten years.) At a private committee meeting that evening, it was reported that Ridley said: "If we don't do something, they will invade. And there is nothing we could do."[13]

The Argentine junta

In the period leading up to the war—and, in particular, following the transfer of power between the military dictators General Jorge Rafael Videla and General Roberto Eduardo Viola late in March 1981—Argentina had been in the midst of devastating economic stagnation and large-scale civil unrest against the military junta that had been governing the country since 1976.[17][18]

In December 1981 there was a further change in the Argentine military regime, bringing to office a new junta headed by General Leopoldo Galtieri (acting president), Air Brigadier Basilio Lami Dozo and Admiral Jorge Anaya. Anaya was the main architect and supporter of a military solution for the long-standing claim over the islands,[19] calculating that the United Kingdom would never respond militarily.[20]

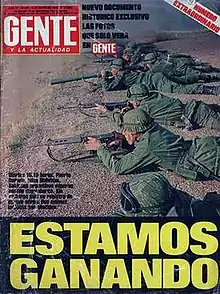

By opting for military action, the Galtieri government hoped to mobilise the long-standing patriotic feelings of Argentines towards the islands, diverting public attention from the chronic economic problems and the ongoing human rights violations of its Dirty War,[21] bolstering the junta's dwindling legitimacy. The newspaper La Prensa speculated on a step-by-step plan beginning with cutting off supplies to the islands, ending in direct actions late in 1982, if the UN talks were fruitless.[22]

The ongoing tension between the two countries over the islands increased on 19 March, when a group of Argentine scrap metal merchants (which had been infiltrated by Argentine Marines)[23] raised the Argentine flag at South Georgia Island, an act that would later be seen as the first offensive action in the war. The Royal Navy ice patrol vessel HMS Endurance was dispatched from Stanley to South Georgia on the 25th in response. The Argentine military junta, suspecting that the UK would reinforce its South Atlantic Forces, ordered the invasion of the Falkland Islands to be brought forward to 2 April.

The UK was initially taken by surprise by the Argentine attack on the South Atlantic islands, despite repeated warnings by Royal Navy captain Nicholas Barker (Commanding Officer of the Endurance) and others. Barker believed that Defence Secretary John Nott's 1981 Defence White Paper (in which Nott described plans to withdraw the Endurance, the UK's only naval presence in the South Atlantic) had sent a signal to the Argentines that the UK was unwilling, and would soon be unable, to defend its territories and subjects in the Falklands.[24][25]

Argentine invasion

On 2 April 1982 Argentine forces mounted amphibious landings, known as Operation Rosario,[26] on the Falkland Islands.[27] The invasion was met with a fierce but brief defence organised by the Falkland Islands' Governor Sir Rex Hunt, giving command to Major Mike Norman of the Royal Marines. The garrison consisted of 68 marines and eleven naval hydrographers,[28] They were assisted by 23 volunteers of the Falkland Islands Defence Force (FIDF), who had few weapons and were used as lookouts.[29] The invasion started with the landing of Lieutenant Commander Guillermo Sanchez-Sabarots' Amphibious Commandos Group, who attacked the empty Moody Brook barracks and then moved on Government House in Stanley. When the 2nd Marine Infantry Battalion with Assault Amphibious Vehicles arrived, the governor ordered a cease fire and surrendered.[30] The governor, his family and the British military personnel were flown to Argentina that afternoon and later repatriated to the United Kingdom.[31]

Initial British response

The British had already taken action prior to the 2 April invasion. In response to events on South Georgia, on 29 March, Ministers decided to send the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) Fort Austin south from the Mediterranean to support HMS Endurance, and the nuclear-powered fleet submarine HMS Spartan from Gibraltar, with HMS Splendid ordered south from Scotland the following day.[32]: 75 [33] Lord Carrington had wished to send a third submarine, but the decision was deferred due to concerns about the impact on operational commitments.[33] Coincidentally, on 26 March, the submarine HMS Superb left Gibraltar and it was assumed in the press she was heading south. There has since been speculation that the effect of those reports was to panic the Argentine junta into invading the Falklands before submarines could be deployed;[33] however, post-war research has established that the final decision to proceed was made at a junta meeting in Buenos Aires on 23 March.[34]

The following day, during a crisis meeting headed by the Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, the Chief of the Naval Staff Admiral Sir Henry Leach, advised them that "Britain could and should send a task force if the islands are invaded". On 1 April, Leach sent orders to a Royal Navy force carrying out exercises in the Mediterranean to prepare to sail south. Following the invasion on 2 April, after an emergency meeting of the cabinet, approval was given to form a task force to retake the islands. This was backed in an emergency sitting of the House of Commons the next day.[35]

Word of the invasion first reached the UK from Argentine sources.[36] A Ministry of Defence operative in London had a short telex conversation with Governor Hunt's telex operator, who confirmed that Argentines were on the island and in control.[36][37] Later that day, BBC journalist Laurie Margolis spoke with an islander at Goose Green via amateur radio, who confirmed the presence of a large Argentine fleet and that Argentine forces had taken control of the island.[36] British military operations in the Falklands War were given the codename Operation Corporate, and the commander of the task force was Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse. Operations lasted from 1 April 1982 to 20 June 1982.[38]

On 6 April, the British Government set up a War Cabinet to provide day-to-day political oversight of the campaign.[39] This was the critical instrument of crisis management for the British with its remit being to "keep under review political and military developments relating to the South Atlantic, and to report as necessary to the Defence and Overseas Policy Committee". The War Cabinet met at least daily until it was dissolved on 12 August. Although Margaret Thatcher is described as dominating the War Cabinet, Lawrence Freedman notes in the Official History of the Falklands Campaign that she did not ignore opposition or fail to consult others. However, once a decision was reached she "did not look back".[39]

United Nations Security Council Resolution 502

On 31 March 1982, the Argentine ambassador to the UN, Eduardo Roca, began attempting to garner support against a British military build-up designed to thwart earlier UN resolutions calling for both countries to resolve the Falklands dispute through discussion.[32]: 134 On 2 April, the night of the invasion, a banquet was held at Roca's official residence for the US ambassador to the UN, Jeane Kirkpatrick, and several high-ranking officials of the United States Department of State and the United States Department of Defense. This led British diplomats to view Kirkpatrick, who had earlier called for closer relationships with South American dictatorships, with considerable suspicion.[40]

On 1 April, London told the UK ambassador to the UN, Sir Anthony Parsons, that an invasion was imminent and he should call an urgent meeting of the Security Council to get a favourable resolution against Argentina.[41] Parsons had to get nine affirmative votes from the 15 Council members (not a simple majority) and to avoid a blocking vote from any of the other four permanent members. The meeting took place at 11:00 am on 3 April, New York time (4:00 pm in London). United Nations Security Council Resolution 502 was adopted by 10 to 1 (with Panama voting against) and 4 abstentions. Significantly, the Soviet Union and China both abstained.[42][43][44] The resolution stated that the UN Security Council was:

Deeply disturbed at reports of an invasion on 2 April 1982 by armed forces of Argentina;

Determining that there exists a breach of the peace in the region of the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas),

Demands an immediate cessation of hostilities;

Demands an immediate withdrawal of all Argentine forces from the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)

Calls on the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom to seek a diplomatic solution to their differences and to respect fully the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

This was a significant win for the UK, giving it the upper hand diplomatically. The draft resolution Parsons submitted had avoided any reference to the sovereignty dispute (which might have worked against the UK): instead it focused on Argentina's breach of Chapter VII of the UN Charter which forbids the threat or use of force to settle disputes.[45] The resolution called for the removal only of Argentine forces: this freed Britain to retake the islands militarily, if Argentina did not leave, by exercising its right to self-defence, that was allowed under the UN Charter.[32]: 141

Argentine occupation

The Argentine Army unit earmarked for the occupation was the 25th Infantry Regiment, a unit of 1,000 conscripts specially selected to represent all the regions of Argentina; it was flown into Stanley Airport as soon as the runway had been cleared.[46] Once it became clear that the British were sending an amphibious task force, there was a general recall of reservists and two brigades of eight infantry regiments and their supporting units were dispatched to the islands. The total Argentinian garrison numbered some 13,000 troops by the beginning of May. The conscripts born in 1963 had only recently been called-up, so they were supplemented by the recall of the previous year's intake. Brigadier General Mario Benjamín Menéndez was appointed Military Governor of the Malvinas.[47]

During the conflict, there was no widespread abuse of the civilian population.[48] Argentine military police arrived with detailed files on many islanders,[49] allowing intelligence officer Major Patricio Dowling to arrest and interrogate islanders who he suspected might lead opposition to the occupation.[49] Initially, Islanders suspected of holding anti-Argentine views were expelled,[49] including the Luxton family[49] (who had lived in the islands since the 1840s) and David Colville,[50] editor of the Falkland's Times. This proved to be counter-productive, as those expelled gave interviews to the press. Subsequently, fourteen other community leaders, including the senior medical officer, were interned at Fox Bay on West Falkland.[51] Concerned by Dowling's actions, senior Argentine officers had him removed from the islands.[49] For almost a month, the civilian population of Goose Green was detained in the village hall in squalid conditions.[48] Less well known is that similar detentions took place in other outlying settlements, and in one case led to the death of an islander denied access to his medication. In the closing moments of the war, some troops began to place booby traps in civilian homes,[52] defiled homes with excrement,[53] destroyed civilian property and committed arson against civilian properties.[54]

Argentine officers and NCO have been accused of torturing their own conscript and volunteer soldiers. Food parcels sent by families were stolen, and troops were starved, and punished for minor misdeeds by being staked to the ground or made to lie in pools of freezing water for hours; many were reported to have died of mistreatment by their own officers. Soldiers were made to sign non-disclosure documents on their return from the Islands.[55]

Shuttle diplomacy

On 8 April, Alexander Haig, the United States Secretary of State, arrived in London on a shuttle diplomacy mission from President Ronald Reagan to broker a peace deal based on an interim authority taking control of the islands pending negotiations. After hearing from Thatcher that the task force would not be withdrawn unless the Argentinians evacuated their troops, Haig headed for Buenos Aires.[56] There he met the Junta and Nicanor Costa Méndez, the foreign minister. Haig was treated coolly and told that Argentinian sovereignty must be a pre-condition of any talks. Returning to London on 11 April, he found the British cabinet in no mood for compromise. Haig flew back to Washington before returning to Buenos Aires for a final protracted round of talks. These made little progress, but just as Haig and his mission were leaving, they were told that Galtieri would meet them at the airport VIP lounge to make an important concession; however, this was cancelled at the last minute. On 30 April, the Reagan administration announced that they would be publicly supporting the United Kingdom.[57]

British task force

_1982.jpg.webp)

_underway_c1981.jpg.webp)

The British government had no contingency plan for an invasion of the islands, and the task force was rapidly put together from whatever vessels were available.[58]

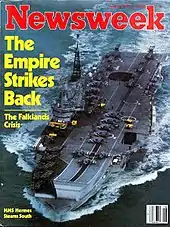

The nuclear-powered submarine Conqueror set sail from Faslane, Scotland on 4 April. The two aircraft carriers Invincible and Hermes and their escort vessels left Portsmouth, England only a day later.[35] On its return to Southampton from a world cruise on 7 April, the ocean liner SS Canberra was requisitioned and set sail two days later with the 3 Commando Brigade aboard.[35] The ocean liner Queen Elizabeth 2 was also requisitioned, and left Southampton on 12 May, with the 5th Infantry Brigade on board.[35] The whole task force eventually comprised 127 ships: 43 Royal Navy vessels, 22 Royal Fleet Auxiliary ships, and 62 merchant ships.[58]

The retaking of the Falkland Islands was considered extremely difficult. The chances of a British counter-invasion succeeding were assessed by the US Navy, according to historian Arthur L. Herman, as "a military impossibility".[59] Firstly, the British were significantly constrained by the disparity in deployable air cover.[60] The British had 42 aircraft (28 Sea Harriers and 14 Harrier GR.3s) available for air combat operations,[61] against approximately 122 serviceable jet fighters, of which about 50 were used as air superiority fighters and the remainder as strike aircraft, in Argentina's air forces during the war.[62] Crucially, the British lacked airborne early warning and control (AEW) aircraft. Planning also considered the Argentine surface fleet and the threat posed by Exocet-equipped vessels or the two Type 209 submarines.[63]

By mid-April, the Royal Air Force had set up an airbase on RAF Ascension Island, co-located with Wideawake Airfield, on the mid-Atlantic British overseas territory of Ascension Island. They included a sizeable force of Avro Vulcan B Mk 2 bombers, Handley Page Victor K Mk 2 refuelling aircraft, and McDonnell Douglas Phantom FGR Mk 2 fighters to protect them. Meanwhile, the main British naval task force arrived at Ascension to prepare for active service. A small force had already been sent south to recapture South Georgia.

Encounters began in April; the British Task Force was shadowed by Boeing 707 aircraft of the Argentine Air Force during their travel to the south.[64] Several of these flights were intercepted by Sea Harriers outside the British-imposed Total Exclusion Zone; the unarmed 707s were not attacked because diplomatic moves were still in progress and the UK had not yet decided to commit itself to armed force. On 23 April, a Brazilian commercial Douglas DC-10 from VARIG Airlines en route to South Africa was intercepted by British Harriers who visually identified the civilian plane.[65]

Recapture of South Georgia and the attack on Santa Fe

The South Georgia force, Operation Paraquet, under the command of Major Guy Sheridan RM, consisted of Marines from 42 Commando, a troop of the Special Air Service (SAS) and Special Boat Service (SBS) troops who were intended to land as reconnaissance forces for an invasion by the Royal Marines, a total of 240 men. All were embarked on RFA Tidespring. First to arrive was the Churchill-class submarine HMS Conqueror on 19 April, and the island was over-flown by a Handley Page Victor aircraft with radar-mapping equipment on 20 April, to establish that no Argentinian ships were in the vicinity.[66]

The first landings of SAS and SBS troops took place on 21 April, but a mission to establish an observation post on the Fortuna Glacier had to be withdrawn after two helicopters crashed in fog and high winds. On 23 April, a submarine alert was sounded and operations were halted, with Tidespring being withdrawn to deeper water to avoid interception. On 24 April, British forces regrouped and headed in to attack.[67]

On 25 April, after resupplying the Argentine garrison in South Georgia, the submarine ARA Santa Fe was spotted on the surface[68] by a Westland Wessex HAS Mk 3 helicopter from HMS Antrim, which attacked the Argentine submarine with depth charges. HMS Plymouth launched a Westland Wasp HAS.Mk.1 helicopter, and HMS Brilliant launched a Westland Lynx HAS Mk 2. The Lynx launched a torpedo, and strafed the submarine with its pintle-mounted general purpose machine gun; the Wessex also fired on Santa Fe with its GPMG. The Wasp from HMS Plymouth as well as two other Wasps launched from HMS Endurance fired AS-12 ASM antiship missiles at the submarine, scoring hits. Santa Fe was damaged badly enough to prevent her from diving. The crew abandoned the submarine at the jetty at King Edward Point on South Georgia.[69]

With Tidespring now far out to sea and the Argentine forces augmented by the submarine's crew, Major Sheridan decided to gather the 76 men he had and make a direct assault that day. After a short forced march by the British troops and a naval bombardment demonstration by two Royal Navy vessels (Antrim and Plymouth), the Argentine forces, a total of 190 men, surrendered without resistance.[70] The message sent from the naval force at South Georgia to London was, "Be pleased to inform Her Majesty that the White Ensign flies alongside the Union Jack in South Georgia. God Save the Queen." The Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, broke the news to the media, telling them to "Just rejoice at that news, and congratulate our forces and the Marines!"[71]

Black Buck raids

On 1 May British operations on the Falklands opened with the "Black Buck 1" attack (of a series of five) on the airfield at Stanley. A Vulcan bomber from Ascension flew an 8,000-nautical-mile (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) round trip, dropping conventional bombs across the runway at Stanley. The mission required repeated refuelling using several Victor K2 tanker aircraft operating in concert, including tanker-to-tanker refuelling.[72] The overall effect of the raids on the war is difficult to determine. The runway was cratered by only one of the twenty one bombs, but as a result, the Argentines realised that their mainland was vulnerable and fighter aircraft were redeployed from the theatre to bases further north.[73]

Historian Lawrence Freedman, who was given access to official sources, comments that the significance of the Vulcan raids remains a subject of controversy.[74] Although they took pressure off the small Sea Harrier force, the raids were costly and used a great deal of resources. The single hit in the centre of the runway was probably the best that could have been expected, but it did reduce the capability of the runway to operate fast jets and caused the Argentine air force to deploy Mirage IIIs to defend the capital.[75] Argentine sources confirm that the Vulcan raids influenced Argentina to shift some of its Mirage IIIs from southern Argentina to the Buenos Aires Defence Zone.[76][77][78] This dissuasive effect was watered down when British officials made clear that there would not be strikes on air bases in Argentina.[79] The raids were later dismissed as propaganda by Falklands veteran Commander Nigel Ward.[80]

Of the five Black Buck raids, three were against Stanley Airfield, with the other two being anti-radar missions using Shrike anti-radiation missiles.[81]

Escalation of the air war

The Falklands had only three airfields. The longest and only paved runway was at the capital, Stanley, and even that was too short to support fast jets. Therefore, the Argentines were forced to launch their major strikes from the mainland, severely hampering their efforts at forward staging, combat air patrols, and close air support over the islands. The effective loiter time of incoming Argentine aircraft was low, limiting the ability of fighters to protect attack aircraft, which were often compelled to attack the first target of opportunity, rather than selecting the most lucrative target.[82]

The first major Argentine strike force comprised 36 aircraft (A-4 Skyhawks, IAI Daggers, English Electric Canberras, and Mirage III escorts), and was sent on 1 May, in the belief that the British invasion was imminent or landings had already taken place. Only a section of Grupo 6 (flying IAI Dagger aircraft) found ships, which were firing at Argentine defences near the islands. The Daggers managed to attack the ships and return safely. This greatly boosted the morale of the Argentine pilots, who now knew they could survive an attack against modern warships, protected by radar ground clutter from the islands and by using a late pop up profile. Meanwhile, other Argentine aircraft were intercepted by BAE Sea Harriers operating from HMS Invincible. A Dagger[83] and a Canberra were shot down.[84]

Combat broke out between Sea Harrier FRS Mk 1 fighters of No. 801 Naval Air Squadron and Mirage III fighters of Grupo 8. Both sides refused to fight at the other's best altitude, until two Mirages finally descended to engage. One was shot down by an AIM-9L Sidewinder air-to-air missile (AAM), while the other escaped but was damaged and without enough fuel to return to its mainland airbase. The plane made for Stanley, where it fell victim to friendly fire from the Argentine defenders.[85]

As a result of this experience, Argentine Air Force staff decided to employ A-4 Skyhawks and Daggers only as strike units, the Canberras only during the night, and Mirage IIIs (without air refuelling capability or any capable AAM) as decoys to lure away the British Sea Harriers. The decoying would be later extended with the formation of the Escuadrón Fénix, a squadron of civilian jets flying 24 hours a day, simulating strike aircraft preparing to attack the fleet. On one of these flights on 7 June, an Air Force Learjet 35A was shot down, killing the squadron commander, Vice Commodore Rodolfo De La Colina, the highest-ranking Argentine officer to die in the war.[86][87]

Stanley was used as an Argentine strongpoint throughout the conflict. Despite the Black Buck and Harrier raids on Stanley airfield (no fast jets were stationed there for air defence) and overnight shelling by detached ships, it was never out of action entirely. Stanley was defended by a mixture of surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems (Franco-German Roland and British Tigercat) and light anti-aircraft guns, including Swiss-built Oerlikon 35 mm twin anti-aircraft cannons and 30 mm Hispano-Suiza cannon and German Rheinmetall 20 mm twin anti-aircraft cannons. More of the anti-aircraft guns were deployed to the airstrip at Goose Green.[88][89] Lockheed Hercules transport night flights brought supplies, weapons, vehicles, and fuel, and airlifted out the wounded up until the end of the conflict.[90]

The only Argentine Hercules shot down by the British was lost on 1 June when TC-63 was intercepted by a Sea Harrier in daylight[91][92] when it was searching for the British fleet north-east of the islands after the Argentine Navy retired its last SP-2H Neptune due to unreliability.[93]

Various options to attack the home base of the five Argentine Étendards at Río Grande were examined and discounted (Operation Mikado); subsequently five Royal Navy submarines lined up, submerged, on the edge of Argentina's 12-nautical-mile (22 km; 14 mi) territorial limit to provide early warning of bombing raids on the British task force.[94]

Sinking of ARA General Belgrano

.jpg.webp)

On 30 April, the British government had brought into force a 200 nautical mile (370 km; 230 mi) Total Exclusion Zone (TEZ) to replace the previous Maritime Exclusion Zone; aircraft as well as ships of any nation were liable to attack inside it, if they were aiding the Argentinian occupation. Admiral Woodward's carrier battle group of twelve warships and three supply ships entered the TEZ on 1 May, shortly before the first Black Buck raid, intending to degrade Argentinian air and sea forces before the arrival of the amphibious group two weeks later.[95] In anticipation, Admiral Anaya had deployed all his available warships into three task groups. The first was centred around the aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo with two old but missile-armed destroyers, and a second comprised three modern frigates. Both these groups were intended to approach the TEZ from the north. A third group approaching from the south was led by the Second World War-vintage Argentine light cruiser ARA General Belgrano;[96] although old, her large guns and heavy armour made her a serious threat, and she was escorted by two modern Type 42 guided-missile destroyers, armed with Exocet missiles.[97]

On 1 May, the British nuclear-powered submarine HMS Conqueror (one of three patrolling the TEZ) located the Belgrano group and followed it until the following day, when it was about 12 hours away from the Task Force and just outside the Total Exclusion Zone. Admiral Woodward was aware of the Argentinian carrier group approaching from the other direction, and ordered the cruiser to be attacked to avoid being caught in a pincer movement; he was unaware that the Veinticinco de Mayo had failed to gain enough headwind to launch her aircraft. The order to sink the cruiser was confirmed by the War Cabinet in London and the General Belgrano was hit by two torpedoes at 4 pm local time on 2 May, sinking an hour later.[98] 321 members of General Belgrano's crew, along with two civilians on board the ship, died in the incident. More than 700 men were eventually rescued from the open ocean despite cold seas and stormy weather, enduring up to 30 hours in overcrowded life rafts.[99] The loss of General Belgrano drew heavy criticism from Latin American countries and from opponents of the war in Britain; support for the British cause wavered amongst some European allies, but critically, the United States remained supportive.[100]

Regardless of controversies over the sinking — including disagreement about the exact nature of the exclusion zone and whether General Belgrano had been returning to port at the time of the sinking — it had a crucial strategic effect: the elimination of the Argentine naval threat. After her loss, the entire Argentine fleet, with the exception of the diesel-powered submarine ARA San Luis,[68] returned to port and did not leave again during the fighting. This had the secondary effect of allowing the British to redeploy their nuclear submarines to the coast of Argentina, where they were able to provide early warning of outgoing air attacks leaving mainland bases.[101] However, settling the controversy in 2003, the ship's captain Hector Bonzo confirmed that General Belgrano had actually been manoeuvering, not sailing away from the exclusion zone, and that the captain had orders to sink any British ship he could find.[102]

In a separate incident later that night, British forces engaged an Argentine patrol gunboat, the ARA Alferez Sobral, that was searching for the crew of an Argentine Air Force Canberra light bomber shot down on 1 May. Two Royal Navy Lynx helicopters, from HMS Coventry and HMS Glasgow, fired four Sea Skua missiles at her. Badly damaged and with eight crew dead, Alferez Sobral managed to return to Puerto Deseado two days later.[103] The Canberra's crew were never found.[104]

Sinking of HMS Sheffield

.jpg.webp)

On 4 May, two days after the sinking of General Belgrano, the British lost the Type 42 destroyer HMS Sheffield to fire following an Exocet missile strike from the Argentine 2nd Naval Air Fighter/Attack Squadron.[105]

Sheffield had been ordered forward with two other Type 42s to provide a long-range radar and medium-high altitude missile picket far from the British carriers. She was struck amidships, with devastating effect, ultimately killing 20 crew members and severely injuring 24 others. The ship was abandoned several hours later, gutted and deformed by fires. For four days she was kept afloat for inspections and the hope that she might attract Argentinian submarines which could be hunted by helicopter. The decision was then taken to tow her to Ascension, but while under tow by HMS Yarmouth, she finally sank east of the Falklands on 10 May.[106]

The incident is described in detail by Admiral Sandy Woodward in his book One Hundred Days, in Chapter One. Woodward was a former commanding officer of Sheffield.[107] The destruction of Sheffield, the first Royal Navy ship sunk in action since the Second World War, had a profound impact on the War Cabinet and the British public as a whole, bringing home the fact that the conflict was now an actual shooting war.[108]

Diplomatic activity

The tempo of operations increased throughout the first half of May as the United Nations' attempts to mediate a peace were rejected by the Argentines. The final British negotiating position was presented to Argentina by UN Secretary General Pérez de Cuéllar on 18 May 1982. In it, the British abandoned their previous "red-line" that British administration of the islands should be restored on the withdrawal of Argentine forces, as supported by United Nations Security Council Resolution 502.[109]

Instead, it proposed a UN administrator should supervise the mutual withdrawal of both Argentine and British forces, then govern the islands in consultation with the representative institutions of the islands, including Argentines, although no Argentines lived there. Reference to "self-determination" of the islanders was dropped and the British proposed that future negotiations over the sovereignty of the islands should be conducted by the UN.[110] However, the proposals were rejected by the Argentinians on the same day.[111]

Special forces operations

Given the threat to the British fleet posed by the Étendard-Exocet combination, plans were made to use C-130s to fly in some SAS troops to attack the home base of the five Étendards at Río Grande, Tierra del Fuego. The operation was codenamed "Mikado". The operation was later scrapped, after acknowledging that its chances of success were limited, and replaced with a plan to use the submarine HMS Onyx to drop SAS operatives several miles offshore at night for them to make their way to the coast aboard rubber inflatables and proceed to destroy Argentina's remaining Exocet stockpile.[112]

An SAS reconnaissance team was dispatched to carry out preparations for a seaborne infiltration. A Westland Sea King helicopter carrying the assigned team took off from HMS Invincible on the night of 17 May, but bad weather forced it to land 50 miles (80 km) from its target and the mission was aborted.[113] The pilot flew to Chile, landed south of Punta Arenas, and dropped off the SAS team. The helicopter's crew of three then destroyed the aircraft, surrendered to Chilean police on 25 May, and were repatriated to the UK after interrogation. The discovery of the burnt-out helicopter attracted considerable international attention. Meanwhile, the SAS team crossed the border and penetrated into Argentina, but cancelled their mission after the Argentines suspected an SAS operation and deployed some 2,000 troops to search for them. The SAS men were able to return to Chile, and took a civilian flight back to the UK.[114]

On 14 May the SAS carried out a raid on Pebble Island on the Falklands, where the Argentine Navy had taken over a grass airstrip map for FMA IA 58 Pucará light ground-attack aircraft and Beechcraft T-34 Mentors, which resulted in the destruction of several aircraft.[nb 1][115]

On 15 May, SBS teams were inserted by HMS Brilliant at Grantham Sound to reconnoitre and observe the landing beaches at San Carlos Bay.[116] On the evening of 20 May, the day before the main landings, an SBS troop and artillery observers were landed by Wessex helicopters for an assault on an Argentinian observation post at Fanning Head which overlooked the entrance the bay; meanwhile, the SAS conducted a diversionary raid at Darwin.[117]

Air attacks

_underway_in_the_Atlantic_Ocean%252C_circa_in_1981_(6417242).jpg.webp)

In the landing zone, the limitations of the British ships' anti-aircraft defences were demonstrated in the sinking of HMS Ardent on 21 May which was hit by nine bombs,[118] and HMS Antelope (F170) on 24 May when attempts to defuse unexploded bombs failed.[119] Out at sea with the carrier battle group, MV Atlantic Conveyor was struck by an air-launched Exocet on 25 May, which caused the loss of three out of four Chinook and five Wessex helicopters as well as their maintenance equipment and facilities, together with runway-building equipment and tents. This was a severe blow from a logistical perspective. Twelve of her crew members were killed.[120]

Also lost on 25 May was HMS Coventry, a sister to Sheffield, whilst in company with HMS Broadsword after being ordered to act as a decoy to draw away Argentine aircraft from other ships at San Carlos Bay.[121] HMS Argonaut and HMS Brilliant were moderately damaged.[62] However, many British ships escaped being sunk because of limitations imposed by circumstances on Argentine pilots. To avoid the highest concentration of British air defences, Argentine pilots released bombs at very low altitude, and hence those bomb fuzes did not have sufficient time to arm before impact. The low release of the retarded bombs (some of which the British had sold to the Argentines years earlier) meant that many never exploded, as there was insufficient time in the air for them to arm themselves.[nb 2] The pilots would have been aware of this—but due to the high concentration required to avoid surface-to-air missiles, anti-Aircraft Artillery (AAA), and British Sea Harriers, many failed to climb to the necessary release point. The Argentine forces solved the problem by fitting improvised retarding devices, allowing the pilots to effectively employ low-level bombing attacks on 8 June.

.jpg.webp)

Thirteen bombs hit British ships without detonating.[122] Lord Craig, the retired Marshal of the Royal Air Force, is said to have remarked: "Six better fuses and we would have lost"[123] although Ardent and Antelope were both lost despite the failure of bombs to explode, and Argonaut was out of action. The fuzes were functioning correctly, and the bombs were simply released from too low an altitude.[124][125] The Argentines lost 22 aircraft in the attacks.[nb 3]

In his autobiographical account of the Falklands War, Admiral Woodward blamed the BBC World Service for disclosing information that led the Argentines to change the retarding devices on the bombs. The World Service reported the lack of detonations after receiving a briefing on the matter from a Ministry of Defence official. He describes the BBC as being more concerned with being "fearless seekers after truth" than with the lives of British servicemen.[124] Colonel 'H'. Jones levelled similar accusations against the BBC after they disclosed the impending British attack on Goose Green by 2 Para.[126]

On 30 May, two Super Étendards, one carrying Argentina's last remaining Exocet, escorted by four A-4C Skyhawks each with two 500 lb bombs, took off to attack Invincible.[127] Argentine intelligence had sought to determine the position of the carriers from analysis of aircraft flight routes from the task force to the islands.[127] However, the British had a standing order that all aircraft conduct a low level transit when leaving or returning to the carriers to disguise their position.[128] This tactic compromised the Argentine attack, which focused on a group of escorts 40 miles (64 km) south of the carrier group.[129] Two of the attacking Skyhawks[129] were shot down by Sea Dart missiles fired by HMS Exeter,[127] with HMS Avenger claiming to have shot down the Exocet missile with her 4.5" gun (although this claim is disputed).[130] No damage was caused to any British vessels.[127] During the war, Argentina claimed to have damaged Invincible and continues to do so to this day,[131] although no evidence of any such damage has been produced or uncovered.[62][132]

Land battles

San Carlos – Bomb Alley

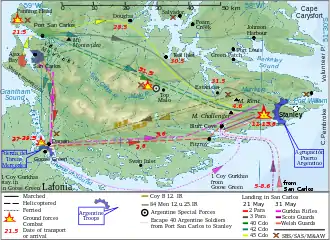

During the night of 21 May, the British Amphibious Task Group under the command of Commodore Michael Clapp (Commodore, Amphibious Warfare – COMAW) mounted Operation Sutton, the amphibious landing on beaches around San Carlos Water,[nb 4] on the northwestern coast of East Falkland facing onto Falkland Sound. The bay, known as Bomb Alley by British forces, was the scene of repeated air attacks by low-flying Argentine jets.[133][134]

The 4,000 men of 3 Commando Brigade were put ashore as follows: 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment (2 Para) from the RORO ferry Norland and 40 Commando Royal Marines from the amphibious ship HMS Fearless were landed at San Carlos (Blue Beach), 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment (3 Para) from the amphibious ship HMS Intrepid was landed at Port San Carlos (Green Beach) and 45 Commando from RFA Stromness was landed at Ajax Bay (Red Beach).[135] Notably, the waves of eight LCUs and eight LCVPs were led by Major Ewen Southby-Tailyour, who had commanded the Falklands detachment NP8901 from March 1978 to 1979. 42 Commando on the ocean liner SS Canberra was a tactical reserve. Units from the Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers, etc. and armoured reconnaissance vehicles were also put ashore with the landing craft, the Round Table class LSL and mexeflote barges. Rapier missile launchers were carried as underslung loads of Sea Kings for rapid deployment.[136]

By dawn the next day, they had established a secure beachhead from which to conduct offensive operations. Brigadier Julian Thompson established his brigade headquarters in dugouts near San Carlos Settlement.[137]

Goose Green

From early on 27 May until 28 May, 2 Para approached and attacked Darwin and Goose Green, which was held by the Argentine 12th Infantry Regiment. 2 Para’s 500 men had naval gunfire support from HMS Arrow[85] and artillery support from 8 Commando Battery and the Royal Artillery. After a tough struggle that lasted all night and into the next day, the British won the battle; in all, 18 British and 47 Argentine soldiers were killed. A total of 961 Argentine troops (including 202 Argentine Air Force personnel of the Condor airfield) were taken prisoner.

The BBC announced the taking of Goose Green on the BBC World Service before it had actually happened. During this attack Lieutenant Colonel H. Jones, the commanding officer of 2 Para, was killed at the head of his battalion while charging into the well-prepared Argentine positions. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

With the sizeable Argentine force at Goose Green out of the way, British forces were now able to break out of the San Carlos beachhead. On 27 May, men of 45 Cdo and 3 Para started a loaded march across East Falkland towards the coastal settlement of Teal Inlet.

Special forces on Mount Kent

Meanwhile, 42 Commando prepared to move by helicopter to Mount Kent.[nb 5] Unknown to senior British officers, the Argentine generals were determined to tie down the British troops in the Mount Kent area, and on 27 and 28 May they sent transport aircraft loaded with Blowpipe surface-to-air missiles and commandos (602nd Commando Company and 601st National Gendarmerie Special Forces Squadron) to Stanley. This operation was known as Autoimpuesta ("Self-imposed").

For the next week, the SAS and the Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre (M&AWC) of 3 Commando Brigade waged intense patrol battles with patrols of the volunteers' 602nd Commando Company under Major Aldo Rico, normally second in Command of the 22nd Mountain Infantry Regiment. Throughout 30 May, Royal Air Force Harriers were active over Mount Kent. One of them, Harrier XZ963, flown by Squadron Leader Jerry Pook—in responding to a call for help from D Squadron, attacked Mount Kent's eastern lower slopes, which led to its loss through small-arms fire. Pook was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.[138] On 31 May, the M&AWC defeated Argentine Special Forces at the skirmish at Top Malo House. A 13-strong Argentine Army Commando detachment (Captain José Vercesi's 1st Assault Section, 602nd Commando Company) found itself trapped in a small shepherd's house at Top Malo. The Argentine commandos fired from windows and doorways and then took refuge in a stream bed 200 metres (700 ft) from the burning house. Completely surrounded, they fought 19 M&AWC marines under Captain Rod Boswell for 45 minutes until, with their ammunition almost exhausted, they elected to surrender.

Three Cadre members were badly wounded. On the Argentine side, there were two dead, including Lieutenant Ernesto Espinoza and Sergeant Mateo Sbert (who were posthumously decorated for their bravery). Only five Argentines were left unscathed. As the British mopped up Top Malo House, Lieutenant Fraser Haddow's M&AWC patrol came down from Malo Hill, brandishing a large Union Flag. One wounded Argentine soldier, Lieutenant Horacio Losito, commented that their escape route would have taken them through Haddow's position.[139]

601st Commando tried to move forward to rescue 602nd Commando Company on Estancia Mountain. Spotted by 42 Commando, they were engaged with L16 81mm mortars and forced to withdraw to Two Sisters mountain. The leader of 602nd Commando Company on Estancia Mountain realised his position had become untenable and after conferring with fellow officers ordered a withdrawal.[140]

The Argentine operation also saw the extensive use of helicopter support to position and extract patrols; the 601st Combat Aviation Battalion also suffered casualties. At about 11:00 am on 30 May, an Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma helicopter was brought down by a shoulder-launched FIM-92 Stinger surface-to-air missile (SAM) fired by the SAS in the vicinity of Mount Kent. Six Argentine National Gendarmerie Special Forces were killed and eight more wounded in the crash.[141]

As Brigadier Thompson commented, "It was fortunate that I had ignored the views expressed by Northwood HQ that reconnaissance of Mount Kent before insertion of 42 Commando was superfluous. Had D Squadron not been there, the Argentine Special Forces would have caught the Commando before de-planing and, in the darkness and confusion on a strange landing zone, inflicted heavy casualties on men and helicopters."[142]

Bluff Cove and Fitzroy

By 1 June, with the arrival of a further 5,000 British troops of the 5th Infantry Brigade, the new British divisional commander, Major General Jeremy Moore RM, had sufficient force to start planning an offensive against Stanley. During this build-up, the Argentine air assaults on the British naval forces continued, killing 56. Of the dead, 32 were from the Welsh Guards on RFA Sir Galahad and RFA Sir Tristram on 8 June. According to Surgeon-Commander Rick Jolly of the Falklands Field Hospital, more than 150 men suffered burns and injuries of some kind in the attack, including Simon Weston.[143]

The Guards were sent to support an advance along the southern approach to Stanley. On 2 June, a small advance party of 2 Para moved to Swan Inlet house in a number of Army Westland Scout helicopters. Telephoning ahead to Fitzroy, they discovered that the area was clear of Argentines and (exceeding their authority) commandeered the one remaining RAF Chinook helicopter to frantically ferry another contingent of 2 Para ahead to Fitzroy (a settlement on Port Pleasant) and Bluff Cove (a settlement on Port Fitzroy).[144]

This uncoordinated advance caused great difficulties in planning for the commanders of the combined operation, as they now found themselves with 30 miles (48 km) of indefensible positions, strung along their southern flank. Support could not be sent by air as the single remaining Chinook was already heavily oversubscribed. The soldiers could march, but their equipment and heavy supplies would need to be ferried by sea.

Plans were drawn up for half the Welsh Guards to march light on the night of 2 June, whilst the Scots Guards and the second half of the Welsh Guards were to be ferried from San Carlos Water in the Landing Ship Logistics (LSL) Sir Tristram and the landing platform dock (LPD) Intrepid on the night of 5 June. Intrepid was planned to stay one day and unload itself and as much of Sir Tristram as possible, leaving the next evening for the relative safety of San Carlos. Escorts would be provided for this day, after which Sir Tristram would be left to unload using a Mexeflote (a powered raft) for as long as it took to finish.[145]

Political pressure from above to not risk the LPD forced Commodore Michael Clapp to alter this plan. Two lower-value LSLs would be sent, but with no suitable beaches to land on, Intrepid's landing craft would need to accompany them to unload. A complicated operation across several nights with Intrepid and her sister ship Fearless sailing half-way to dispatch their craft was devised.[146]

The attempted overland march by half the Welsh Guards failed, possibly as they refused to march light and attempted to carry their equipment.[147] They returned to San Carlos and landed directly at Bluff Cove when Fearless dispatched her landing craft. Sir Tristram sailed on the night of 6 June and was joined by Sir Galahad at dawn on 7 June. Anchored 1,200 feet (370 m) apart in Port Pleasant, the landing ships were near Fitzroy, the designated landing point. The landing craft should have been able to unload the ships to that point relatively quickly, but confusion over the ordered disembarkation point (the first half of the Guards going direct to Bluff Cove) resulted in the senior Welsh Guards infantry officer aboard insisting that his troops should be ferried the far longer distance directly to Port Fitzroy/Bluff Cove. The alternative was for the infantrymen to march via the recently repaired Bluff Cove bridge (destroyed by retreating Argentine combat engineers) to their destination, a journey of around seven miles (11 km).[148]

On Sir Galahad's stern ramp there was an argument about what to do. The officers on board were told that they could not sail to Bluff Cove that day. They were told that they had to get their men off ship and onto the beach as soon as possible as the ships were vulnerable to enemy aircraft. It would take 20 minutes to transport the men to shore using the LCU and Mexeflote. They would then have the choice of walking the seven miles to Bluff Cove or wait until dark to sail there. The officers on board said that they would remain on board until dark and then sail. They refused to take their men off the ship. They possibly doubted that the bridge had been repaired due to the presence on board Sir Galahad of the Royal Engineer Troop whose job it was to repair the bridge. The Welsh Guards were keen to rejoin the rest of their Battalion, who were potentially facing the enemy without their support. They had also not seen any enemy aircraft since landing at San Carlos and may have been overconfident in the air defences. Ewen Southby-Tailyour gave a direct order for the men to leave the ship and go to the beach; the order was ignored.[149]

The longer journey time of the landing craft taking the troops directly to Bluff Cove and the squabbling over how the landing was to be performed caused an enormous delay in unloading. This had disastrous consequences, since the ships were visible to Argentinian troops on Mount Harriet, some ten miles (16 km) distant.[150] Without escorts, having not yet established their air defence, and still almost fully laden, the two LSLs in Port Pleasant were sitting targets for eight Argentine A-4 Skyhawks. A coordinated sortie by six Daggers attacked HMS Plymouth, which had the effect of drawing off the patrolling Sea Harriers. At 17.00, the Skyhawks attacked from seaward, hitting Sir Galahad with three bombs; although none exploded, they caused fierce fires which quickly grew out of control. Two bombs hit Sir Tristram, also starting fires and causing the ship to be abandoned, but the damage was not as serious. Three Sea King and a Wessex helicopter ferried the wounded to an advanced dressing station which was set up on the shore.[151]

British casualties were 48 killed and 115 wounded.[152] Three Argentine pilots were also killed. The air strike delayed the scheduled British ground attack on Stanley by two days.[153] The British casualties amounted to two infantry companies, but it was decided not to release detailed casualty figures because intelligence indicated that Argentinian commanders believed that a much more severe reverse had been inflicted. However, the disaster at Port Pleasant (although often known as Bluff Cove) would provide the world with some of the most sobering images of the war as ITV News video showed helicopters hovering in thick smoke to winch survivors from the burning landing ships.[154]

Fall of Stanley

On the night of 11 June, after several days of painstaking reconnaissance and logistic build-up, British forces launched a brigade-sized night attack against the heavily defended ring of high ground surrounding Stanley. Units of 3 Commando Brigade, supported by naval gunfire from several Royal Navy ships, simultaneously attacked in the Battle of Mount Harriet, Battle of Two Sisters, and Battle of Mount Longdon. Mount Harriet was taken at a cost of 2 British and 18 Argentine soldiers. At Two Sisters, the British faced both enemy resistance and friendly fire, but managed to capture their objectives. The toughest battle was at Mount Longdon. British forces were bogged down by rifle, mortar, machine gun, artillery and sniper fire, and ambushes. Despite this, the British continued their advance.[155]

During this battle, 14 were killed when HMS Glamorgan, straying too close to shore while returning from the gun line, was struck by an improvised trailer-based Exocet MM38 launcher taken from the destroyer ARA Seguí by Argentine Navy technicians.[156] On the same day, Sergeant Ian McKay of 4 Platoon, B Company, 3 Para died in a grenade attack on an Argentine bunker; he received a posthumous Victoria Cross for his actions.[157] After a night of fierce fighting, all objectives were secured. Both sides suffered heavy losses.[158]

The second phase of attacks began on the night of 13 June, and the momentum of the initial assault was maintained. 2 Para, with light armour support from the Blues and Royals, captured Wireless Ridge, with the loss of 3 British and 25 Argentine lives, and the 2nd Battalion, Scots Guards captured Mount Tumbledown at the Battle of Mount Tumbledown, which cost 10 British and 30 Argentine lives.[159] A simultaneous special forces raid by the SAS and SBS in fast boats to attack the oil tanks in Stanley Harbour was beaten off by anti-aircraft guns.[160]

With the last natural defence line at Mount Tumbledown breached, the Argentine town defences of Stanley began to falter. In the morning gloom, one company commander got lost and his junior officers became despondent. Private Santiago Carrizo of the 3rd Regiment described how a platoon commander ordered them to take up positions in the houses and "if a Kelper resists, shoot him", but the entire company did nothing of the kind.[161] A daylight attack on Mount William by the Gurkhas, delayed from the previous night by the fighting at Tumbledown, ended in anticlimax when the Argentinian positions were found to be deserted.[162]

A ceasefire was declared on 14 June and Thatcher announced the commencement of surrender negotiations. The commander of the Argentine garrison in Stanley, Brigade General Mario Menéndez, surrendered to Major General Jeremy Moore the same day.[163]

Recapture of South Sandwich Islands

On 20 June, the British retook the South Sandwich Islands, which involved accepting the surrender of the Southern Thule Garrison at the Corbeta Uruguay base, and declared hostilities over. Argentina had established Corbeta Uruguay in 1976, but prior to 1982 the United Kingdom had contested the existence of the Argentine base only through diplomatic channels.[164]

Position of third-party countries

Commonwealth

The UK received political support from member countries of the Commonwealth of Nations. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand withdrew their diplomats from Buenos Aires.[165]

New Zealand

The New Zealand government expelled the Argentine ambassador following the invasion. The Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon, was in London when the war broke out[166] and in an opinion piece published in The Times he said: "The military rulers of Argentina must not be appeased … New Zealand will back Britain all the way." Broadcasting on the BBC World Service, he told the Falkland Islanders: "This is Rob Muldoon. We are thinking of you and we are giving our full and total support to the British Government in its endeavours to rectify this situation and get rid of the people who have invaded your country."[167] On 20 May 1982, he announced that New Zealand would make HMNZS Canterbury, a Leander-class frigate, available for use where the British thought fit to release a Royal Navy vessel for the Falklands.[168] In the House of Commons afterwards, Margaret Thatcher said: "…the New Zealand Government and people have been absolutely magnificent in their support for this country [and] the Falkland Islanders, for the rule of liberty and of law".[167][169]

Australia

Embarrassed by the generous response of New Zealand, the Australian prime minister, Malcolm Fraser, was rushed into offering to cancel the intended purchase of HMS Invincible, which was quickly accepted by the British. However, this left the Royal Australian Navy without a replacement for their only aircraft carrier, HMAS Melbourne (R21), which was in the process of decommissioning.[170]

France

The French president, François Mitterrand, declared an embargo on French arms sales and assistance to Argentina.[171] In addition, France allowed UK aircraft and warships use of its port and airfield facilities at Dakar in Senegal[172] and France provided dissimilar aircraft training so that Harrier pilots could train against the French aircraft used by Argentina.[173] French intelligence also cooperated with Britain to prevent Argentina from obtaining more Exocet missiles on the international market.[174] In a 2002 interview, and in reference to this support, John Nott, the then British Defence Secretary, had described France as Britain's 'greatest ally'. In 2012, it came to light that while this support was taking place, a French technical team, employed by Dassault and already in Argentina, remained there throughout the war despite the presidential decree. The team had provided material support to the Argentines, identifying and fixing faults in Exocet missile launchers. John Nott said he had known the French team was there but said its work was thought not to be of any importance. An adviser to the then French government denied any knowledge at the time that the technical team was there. The French DGSE did know the team was there as they had an informant in the team but decried any assistance the team gave: "It's bordering on an act of treason, or disobedience to an embargo". John Nott, when asked if he felt let down by the French said "If you're asking me: 'Are the French duplicitous people?' the answer is: 'Of course they are, and they always have been".[171]

United States

Declassified cables show the U.S. felt that Thatcher had not considered diplomatic options, and also feared that a protracted conflict could draw the Soviet Union on Argentina's side,[175] and initially tried to mediate an end to the conflict through "shuttle diplomacy". However, when Argentina refused the U.S. peace overtures, U.S. Secretary of State Alexander Haig announced that the United States would prohibit arms sales to Argentina and provide material support for British operations. Both houses of the U.S. Congress passed resolutions supporting the U.S. action siding with the United Kingdom.[176]

The U.S. provided the United Kingdom with 200 Sidewinder missiles for use by the Harrier jets,[177][178] eight Stinger surface to air missile systems, Harpoon anti-ship missiles and mortar bombs.[179] On Ascension Island, the underground fuel tanks were empty when the British Task Force arrived in mid-April 1982 and the leading assault ship, HMS Fearless, did not have enough fuel to dock when it arrived off Ascension. The United States diverted a supertanker to replenish the fuel tanks of ships there at anchor as well as for storage tanks on the island – approximately 2 million gallons of fuel were supplied.[180] The Pentagon further committed to providing additional support in the event of the war dragging on into the southern hemisphere winter: in this scenario the U.S. committed to providing tanker aircraft to support Royal Air Force missions in Europe, releasing RAF aircraft to support operations over the Falklands.[181]

The United States allowed the United Kingdom to use U.S. communication satellites to allow secure communications between submarines in the Southern Ocean and Naval HQ in Britain. The U.S. also passed on satellite imagery (which it publicly denied[182]) and weather forecast data to the British Fleet.[183]

President Ronald Reagan approved the Royal Navy's request to borrow a Sea Harrier-capable Iwo Jima-class amphibious assault ship (the US Navy had earmarked USS Guam (LPH-9) for this[184]) if the British lost an aircraft carrier. The United States Navy developed a plan to help the British man the ship with American military contractors, likely retired sailors with knowledge of the ship's systems.[185]

Cuba

Argentina itself was politically backed by a number of countries in Latin America (though, notably, not Chile). Several members of the Non-Aligned Movement also backed Argentina's position; notably, Cuba and Nicaragua led a diplomatic effort to rally non-aligned countries from Africa and Asia towards Argentina's position. This initiative came as a surprise to Western observers, as Cuba had no diplomatic relations with Argentina's right-leaning military junta. British diplomats complained that Cuba had "cynically exploited" the crisis to pursue its normalization of relations with Latin American countries; Argentina eventually resumed relations with Cuba in 1983, followed by Brazil in 1986.[186]

Peru

Peru attempted to purchase 12 Exocet missiles from France to be delivered to Argentina, in a failed secret operation.[187][188] Peru also openly sent "Mirages, pilots and missiles" to Argentina during the war.[189] Peru had earlier transferred ten Hercules transport planes to Argentina soon after the British Task Force had set sail in April 1982.[190] Nick van der Bijl records that, after the Argentine defeat at Goose Green, Venezuela and Guatemala offered to send paratroopers to the Falklands.[191]

Chile

At the outbreak of the war, Chile was in negotiations with Argentina for control over the Beagle Channel and feared Argentina would use similar tactics to secure the channel.[192] During this conflict, Argentina had already rejected two attempts at international mediation and tried to exert military pressure on Chile with an operation to occupy the disputed territory. Considering this, Chile refused to support the Argentine position during the war.[193] and gave support to the UK in the form of intelligence about the Argentine military and early warning intelligence on Argentine air movements.[194][195] Throughout the war, Argentina was afraid of a Chilean military intervention in Patagonia and kept some of its best mountain regiments away from the Falklands near the Chilean border as a precaution.[196] The Chilean government also allowed the United Kingdom to requisition the refuelling vessel RFA Tidepool, which Chile had recently purchased and which had arrived at Arica in Chile on 4 April. The ship left port soon afterwards, bound for Ascension Island through the Panama Canal and stopping at Curaçao en route.[197][198][199]

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union described the Falklands as "a disputed territory," recognising Argentina's ambitions over the islands and called for restraint on all sides. Significantly, however, they refrained from vetoing and thus made possible the UN Security Council Resolution 502 demanding the immediate withdrawal of all Argentine troops from the Falklands. The Soviet Union did mount some clandestine logistics operations in favour of the Argentinians.[200] Soviet media frequently criticised the UK and US during the war. Days after the invasion by the Argentinian forces, the Soviets launched additional intelligence satellites into low Earth orbit covering the southern Atlantic Ocean. There are conflicting reports on whether Soviet ocean surveillance data might have played a role in the sinking of HMS Sheffield and HMS Coventry.[201][202][203]

Spain

Spain's position was one of ambiguity, underpinning the basic dilemma of the Spanish foreign policy regarding the articulation of relationships with Latin America and the European Communities.[204] On 2 April 1982, the Council of Ministers issued an official note defending principles of decolonisation and against the use of force.[205] Spain abstained in the vote of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 502, a position justified by the Spanish representative before the UN Jaime de Piniés on the basis that the resolution made no mention to the underlying problem of decolonisation.[205] The Spanish stance throughout the conflict contrasted with those of the countries in its immediate vicinity (EEC members and Portugal).[206]

The Spanish authorities also foiled a covert Argentinian attack on British shipping. The Argentinian Naval Intelligence Service planned an attack on British warships at Gibraltar, code named Operation Algeciras. Three frogmen, recruited from a former anti-government insurgent group, were to plant mines on the ships' hulls. The divers travelled to Spain through France, where the French security services noted their military diving equipment and alerted their Spanish counterparts. They were covertly monitored as they moved from the Argentinian embassy in Madrid to Algeciras, where they were arrested on 17 May by the Guardia Civil and deported.[207]

EEC

The European Economic Community provided economic support by imposing economic sanctions on Argentina. In a meeting on Good Friday, 9 April, at the Egmont Palace, the EEC Political Committee proposed a total import ban from Argentina. Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Luxembourg and Ireland agreed immediately; France, Germany and the Netherlands were persuaded before the meeting ended. Italy, which had close cultural ties with Argentina, consented on the next day.[208]

Ireland

Ireland's position altered during the war. As a rotating member of the United Nations Security Council, it supported Resolution 502. However, on 4 May the Fianna Fáil government led by Charles Haughey decided to oppose EEC sanctions and called for a ceasefire. Haughey justified this as complying with Irish neutrality. Historians have suggested it was an opportunistic appeal to anti-British sentiment and reaction to Haughey's being sidelined during the 1981 republican hunger strike. The strain on British–Irish relations eased when Haughey's government fell in November 1982.[209][210][211]

Israel

According to the book Operation Israel, advisers from Israel Aerospace Industries were already in Argentina and continued their work during the conflict. The book also claims that Israel sold weapons and drop tanks to Argentina in a secret operation via Peru.[212][213]

Sierra Leone

The Sierra Leonian government allowed British task force ships to refuel at Freetown.[214]

The Gambia

VC10 transport aircraft landed at Banjul in The Gambia while flying between the UK and Ascension Island.[172]

Libya

Through Libya, under Muammar Gaddafi, Argentina received 20 launchers and 60 SA-7 missiles (which Argentina later described as "not effective"), as well as machine guns, mortars and mines; all in all, the load of four trips of two Boeing 707s of the AAF, refuelled in Recife with the knowledge and consent of the Brazilian government.[215]

South Africa

The UK had terminated the Simonstown Agreement in 1975, thereby effectively denying the Royal Navy access to ports in South Africa, and instead forcing them to use Ascension Island as a staging post.[216]

Casualties

In total, 907 were killed during the 74 days of the conflict:

- Argentina – 649[217]

- Ejército Argentino (Army) – 194 (16 officers, 35 non-commissioned officers (NCO) and 143 conscript privates)[218]

- Armada de la República Argentina (Navy) – 341 (including 321 in ARA General Belgrano and 4 naval aviators)

- IMARA (Marines) – 34[219]

- Fuerza Aérea Argentina (Air Force) – 55 (including 31 pilots and 14 ground crew)[220]

- Gendarmería Nacional Argentina (Border Guard) – 7

- Prefectura Naval Argentina (Coast Guard) – 2

- United Kingdom – A total of 255 British servicemen and 3 female Falkland Island civilians were killed during the Falklands War.[221]

- Royal Navy – 86 + 2 Hong Kong laundrymen (see below)[222]

- Royal Marines – 27 (2 officers, 14 NCOs and 11 marines)[223]

- Royal Fleet Auxiliary – 4 + 6 Hong Kong sailors[224][225]

- Merchant Navy – 6[224]

- British Army – 123 (7 officers, 40 NCOs and 76 privates)[226][227][228]

- Royal Air Force – 1 (1 officer)[224]

- Falkland Islands civilians – 3 women accidentally killed by British shelling during the night of 11/12 June. The military command identified those killed as Susan Whitley, 30, a British citizen, and Falkland Islands natives Doreen Bonner, 36 and Mary Goodwin, 82.[229][224][230]

Of the 86 Royal Navy personnel, 22 were lost in HMS Ardent, 19 + 1 lost in HMS Sheffield, 19 + 1 lost in HMS Coventry and 13 lost in HMS Glamorgan. Fourteen naval cooks were among the dead, the largest number from any one branch in the Royal Navy.

Thirty-three of the British Army's dead came from the Welsh Guards (32 of whom died on the RFA Sir Galahad in the Bluff Cove Air Attacks), 21 from the 3rd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, 18 from the 2nd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, 19 from the Special Air Service, 3 each from Royal Signals and Royal Army Medical Corps and 8 from each of the Scots Guards and Royal Engineers. The 1st battalion/7th Duke of Edinburgh's Own Gurkha Rifles lost one man.

There were 1,188 Argentine and 777 British injured or wounded.

Red Cross Box

Before British offensive operations began, the British and Argentine governments agreed to establish an area on the high seas where both sides could station hospital ships without fear of attack by the other side. This area, a circle 20 nautical miles in diameter, was referred to as the Red Cross Box (48°30′S 53°45′W), about 45 miles (72 km) north of Falkland Sound.[231] Ultimately, the British stationed four ships (HMS Hydra, HMS Hecla and HMS Herald and the primary hospital ship SS Uganda) within the box,[232] while the Argentines stationed three (ARA Almirante Irízar, ARA Bahía Paraíso and Puerto Deseado).

The hospital ships were non-warships converted to serve as hospital ships.[233] The three British naval vessels were survey vessels and Uganda was a passenger liner. Almirante Irizar was an icebreaker, Bahia Paraiso was an Antarctic supply transport and Puerto Deseado was a survey ship. The British and Argentine vessels operating within the Box were in radio contact and there was some transfer of patients between the hospital ships. For example, the Uganda on four occasions transferred patients to an Argentine hospital ship.[234] Hydra worked with Hecla and Herald to take casualties from Uganda to Montevideo, Uruguay, where a fleet of Uruguayan ambulances met them. RAF VC10 aircraft then flew the casualties to the UK for transfer to the Princess Alexandra Hospital at RAF Wroughton, near Swindon.[235]

Throughout the conflict officials of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) conducted inspections to verify that all concerned were abiding by the rules of the Geneva Conventions. Argentine naval officers also inspected the British casualty ferries in the estuary of the River Plate.

Aftermath

This brief war brought many consequences for all the parties involved, besides the considerable casualty rate and large materiel loss, especially of shipping and aircraft, relative to the deployed military strengths of the opposing sides.

In the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher's popularity increased. The success of the Falklands campaign was widely regarded as a factor in the turnaround in fortunes for the Conservative government, who had been trailing behind the SDP–Liberal Alliance in the opinion polls for months before the conflict began, but following the success in the Falklands the Conservatives returned to the top of the opinion polls by a wide margin and went on to win the following year's general election by a landslide.[236] Subsequently, Defence Secretary Nott's proposed cuts to the Royal Navy were abandoned.

The islanders subsequently had full British citizenship restored in 1983, their quality of life was improved by investments the UK made after the war and by the economic liberalisation that had been stalled through fear of angering Argentina. In 1985, a new constitution was enacted promoting self-government, which has continued to devolve power to the islanders.

In Argentina, defeat in the Falklands War meant that a possible war with Chile was avoided. Further, Argentina returned to a democratic government in the 1983 general election, the first free general election since 1973. It also had a major social impact, destroying the military's image as the "moral reserve of the nation" that they had maintained through most of the 20th century.

A detailed study[237] of 21,432 British veterans of the war commissioned by the UK Ministry of Defence found that between 1982 and 2012 only 95 had died from "intentional self-harm and events of undetermined intent (suicides and open verdict deaths)", a proportion lower than would be expected within the general population over the same period.[238] However, a study of British combat veterans conducted five years after the conflict, found that half of the sample group had suffered some symptoms of Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while 22% were assessed to have the complete syndrome.[239]

"Fortress Falklands"

In the immediate aftermath of the conflict, the British government embarked on a long-term policy of providing the islands with a viable military garrison, known informally as "Fortress Falklands". Initially, an aircraft carrier was kept in the area until the runway at Stanley Airport could be improved to take conventional RAF fighters. A permanent military complex with a runway designed to take long-haul airliners was constructed in the south of East Falkland, RAF Mount Pleasant, which opened in 1985; an associated deep-water port at Mare Harbour was also constructed. A small military outpost was established at King Edward Point on South Georgia, but it was closed in 2001.[240]

Military analysis

Militarily, the Falklands conflict remains one of the largest air-naval combat operations between modern forces since the end of the Second World War. As such, it has been the subject of intense study by military analysts and historians. The most significant "lessons learned" include: the vulnerability of surface ships to anti-ship missiles and submarines, the challenges of co-ordinating logistical support for a long-distance projection of power, and reconfirmation of the importance of tactical air power, including the use of helicopters.

In 1986, the BBC broadcast the Horizon programme, In the Wake of HMS Sheffield, which discussed lessons learned from the conflict, and measures since taken to implement them, such as incorporating greater stealth capabilities and providing better close-in weapon systems for the Fleet. The principal British military responses to the Falklands War were the measures adopted in the December 1982 Defence White Paper.[241]

Memorials

.jpg.webp)

There are several memorials on the Falkland Islands themselves, the most notable of which is the 1982 Liberation Memorial, unveiled in 1984 on the second anniversary of the end of the war. It lists the names of the 255 British military personnel who died during the war and is located in front of the Secretariat Building in Stanley, overlooking Stanley Harbour. The Memorial was funded entirely by the Islanders and is inscribed with the words "In Memory of Those Who Liberated Us".[242]