Stereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, involves the study of the relative spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation.[1] The study of stereochemistry focuses on stereoisomers, which by definition have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in space. For this reason, it is also known as 3D chemistry—the prefix "stereo-" means "three-dimensionality".[2]

An important branch of stereochemistry is the study of chiral molecules.[3] Stereochemistry spans the entire spectrum of organic, inorganic, biological, physical and especially supramolecular chemistry. Stereochemistry includes methods for determining and describing these relationships; the effect on the physical or biological properties these relationships impart upon the molecules in question, and the manner in which these relationships influence the reactivity of the molecules in question (dynamic stereochemistry).

History

Louis Pasteur could rightly be described as the first stereochemist, having observed in 1842 that salts of tartaric acid collected from wine production vessels could rotate the plane of polarized light, but that salts from other sources did not. This property, the only physical property in which the two types of tartrate salts differed, is due to optical isomerism. In 1874, Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Joseph Le Bel explained optical activity in terms of the tetrahedral arrangement of the atoms bound to carbon. Kekulé used tetrahedral models earlier in 1862 but never published these; Emanuele Paternò probably knew of these but was the first to draw and discuss three dimensional structures, such as of 1,2-dibromoethane in the Giornale di Scienze Naturali ed Economiche in 1869.[4] The term "chiral" was introduced by Lord Kelvin in 1904. Arthur Robertson Cushny, Scottish Pharmacologist, in 1908, first offered a definite example of a bioactivity difference between enantiomers of a chiral molecule viz. (-)-Adrenaline is two times more potent than the (±)- form as a vasoconstrictor and in 1926 laid the foundation for chiral pharmacology/stereo-pharmacology[5][6] (biological relations of optically isomeric substances). Later in 1966, the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog nomenclature or Sequence rule was devised to assign absolute configuration to stereogenic/chiral center (R- and S- notation) [7] and extended to be applied across olefinic bonds (E- and Z- notation).

Significance

Cahn–Ingold–Prelog priority rules are part of a system for describing a molecule's stereochemistry. They rank the atoms around a stereocenter in a standard way, allowing the relative position of these atoms in the molecule to be described unambiguously. A Fischer projection is a simplified way to depict the stereochemistry around a stereocenter.

Thalidomide example

An often cited example of the importance of stereochemistry relates to the thalidomide disaster. Thalidomide is a pharmaceutical drug, first prepared in 1957 in Germany, prescribed for treating morning sickness in pregnant women. The drug was discovered to be teratogenic, causing serious genetic damage to early embryonic growth and development, leading to limb deformation in babies. Some of the several proposed mechanisms of teratogenicity involve a different biological function for the (R)- and the (S)-thalidomide enantiomers.[8] In the human body however, thalidomide undergoes racemization: even if only one of the two enantiomers is administered as a drug, the other enantiomer is produced as a result of metabolism.[9] Accordingly, it is incorrect to state that one stereoisomer is safe while the other is teratogenic.[10] Thalidomide is currently used for the treatment of other diseases, notably cancer and leprosy. Strict regulations and controls have been enabled to avoid its use by pregnant women and prevent developmental deformations. This disaster was a driving force behind requiring strict testing of drugs before making them available to the public.

Definitions

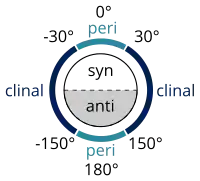

Many definitions that describe a specific conformer (IUPAC Gold Book) exist, developed by William Klyne and Vladimir Prelog, constituting their Klyne–Prelog system of nomenclature:

- a torsion angle of ±60° is called gauche[11]

- a torsion angle between 0° and ±90° is called syn (s)

- a torsion angle between ±90° and 180° is called anti (a)

- a torsion angle between 30° and 150° or between –30° and –150° is called clinal

- a torsion angle between 0° and 30° or 150° and 180° is called periplanar (p)

- a torsion angle between 0° to 30° is called synperiplanar or syn- or cis-conformation (sp)

- a torsion angle between 30° to 90° and –30° to –90° is called synclinal or gauche or skew (sc)[12]

- a torsion angle between 90° to 150°, and –90° to –150° is called anticlinal (ac)

- a torsion angle between ±150° to 180° is called antiperiplanar or anti or trans (ap).

Torsional strain results from resistance to twisting about a bond.

Types

- Atropisomerism

- Cis–trans isomerism

- Conformational isomerism

- Diastereomers

- Enantiomers

See also

- Alkane stereochemistry

- Chiral resolution, which often involves crystallization

- Chirality (chemistry) (R/S, d/l)

- Chiral switch

- Solid-state chemistry

- VSEPR theory

- Skeletal formula#Stereochemistry which describes how stereochemistry is denoted in skeletal formulae.

References

- Ernest Eliel Basic Organic Stereochemistry ,2001 ISBN 0471374997; Bernard Testa and John Caldwell Organic Stereochemistry: Guiding Principles and Biomedicinal Relevance 2014 ISBN 3906390691; Hua-Jie Zhu Organic Stereochemistry: Experimental and Computational Methods 2015 ISBN 3527338225; László Poppe, Mihály Nógrádi, József Nagy, Gábor Hornyánszky, Zoltán Boros Stereochemistry and Stereoselective Synthesis: An Introduction 2016 ISBN 3527339019

- "the definition of stereo-". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2010-06-09.

- March, Jerry (1985), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (3rd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-85472-7

- Paternò, Emanuele (1869). "Intorno all'azione del percloruro di fosforo sul clorale". Giorn. Sci. Nat. Econ. 5: 117–122.

- Smith, Silas W. (2009-05-04). "Chiral Toxicology: It's the Same Thing…Only Different". Toxicological Sciences. 110 (1): 4–30. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp097. ISSN 1096-6080. PMID 19414517.

- Patočka, Jiří; Dvořák, Aleš (2004-07-31). "Biomedical aspects of chiral molecules". Journal of Applied Biomedicine. 2 (2): 95–100. doi:10.32725/jab.2004.011.

- Cahn, R. S.; Ingold, Christopher; Prelog, V. (April 1966). "Specification of Molecular Chirality". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 5 (4): 385–415. doi:10.1002/anie.196603851. ISSN 0570-0833.

- Stephens TD, Bunde CJ, Fillmore BJ (June 2000). "Mechanism of action in thalidomide teratogenesis". Biochemical Pharmacology. 59 (12): 1489–99. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00388-3. PMID 10799645.

- Teo SK, Colburn WA, Tracewell WG, Kook KA, Stirling DI, Jaworsky MS, Scheffler MA, Thomas SD, Laskin OL (2004). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of thalidomide". Clin. Pharmacokinet. 43 (5): 311–327. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443050-00004. PMID 15080764. S2CID 37728304.

- Francl, Michelle (2010). "Urban legends of chemistry". Nature Chemistry. 2 (8): 600–601. Bibcode:2010NatCh...2..600F. doi:10.1038/nchem.750. PMID 20651711.

- Anslyn, Eric V. and Dougherty, Dennis A. Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science (2005), 1083 pp. ISBN 1-891389-31-9

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "gauche". doi:10.1351/goldbook.G02593