Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (/ˌtæmɪl ˈnɑːduː/; Tamil: [ˈtamiɻ ˈnaːɽɯ] (![]() listen), abbr. TN) is a state in southern India. It is the tenth largest Indian state by area and the sixth largest by population. Its capital and largest city is Chennai. Tamil Nadu is the home of the Tamil people, whose Tamil language—one of the longest surviving classical languages in the world—is widely spoken in the state and serves as its official language.

listen), abbr. TN) is a state in southern India. It is the tenth largest Indian state by area and the sixth largest by population. Its capital and largest city is Chennai. Tamil Nadu is the home of the Tamil people, whose Tamil language—one of the longest surviving classical languages in the world—is widely spoken in the state and serves as its official language.

Tamil Nadu | |

|---|---|

_(14354574611).jpg.webp) .jpg.webp) _(37464519366).jpg.webp)    From top, left to right: Brihadisvara Temple, Shore Temple, Ranganathaswamy Temple, Nilgiri Mountains, Hogenakkal Falls and Thiruvalluvar Statue | |

Emblem | |

| Motto(s): Vāymaiyē vellum (Truth alone triumphs) | |

| Anthem: "Tamil Thai Valthu" (Invocation to Mother Tamil) | |

Location of Tamil Nadu in India | |

| Coordinates: 13.09°N 80.27°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | South India |

| Formation | 26 January 1950 |

| Capital and Largest City | Chennai |

| Largest Metro | Greater Chennai Metropolitan Area |

| Districts | 38 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Government of Tamil Nadu |

| • Governor | R. N. Ravi |

| • Chief Minister | M. K. Stalin (DMK) |

| • State Legislature | Unicameral (234 seats)[1] |

| • National Parliament | Lok Sabha (39 seats) Rajya Sabha (18 seats) |

| • High Court | Madras High Court |

| Area | |

| • Total | 130,058 km2 (50,216 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 10th |

| Population (2011)[2] | |

| • Total | 72,147,030 |

| • Rank | 6th |

| • Density | 550/km2 (1,400/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | |

| GDP (2021–2022) | |

| • Total | |

| • Per capita | |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Tamil[4] |

| • Additional official | English[4] |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-TN |

| Vehicle registration | TN |

| HDI (2019) | high · 11th |

| Literacy (2017) | |

| Sex ratio (2019) | 996 ♀/1000 ♂ |

| Coastline | 1,076 km (669 mi) |

| Website | www |

| Symbols of Tamil Nadu | |

| Emblem |  |

| Song | "Invocation to Goddess Tamil" |

| Dance | |

| Mammal | _female_head.jpg.webp) |

| Bird | |

| Butterfly | |

| Flower | |

| Fruit | |

| Tree | _-_Jardin_de_Nong-Nooch.jpg.webp) |

| Sport | |

| ^# Jana Gana Mana is the national anthem, while Invocation to Mother Tamil is the state song/anthem. ^† Established in 1773; Madras State was formed in 1950 and renamed as Tamil Nadu on 14 January 1969[6] | |

The state lies in the southernmost part of the Indian peninsula, and is bordered by the Indian union territory of Puducherry and the states of Kerala, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh, as well as an international maritime border with Sri Lanka. It is bounded by the Western Ghats in the west, the Eastern Ghats in the north, the Bay of Bengal in the east, the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Strait to the south-east, and the Indian Ocean in the south.

The at-large Tamilakam region that has been inhabited by Tamils was under several regimes, such as the Sangam era rulers of the Chera, Chola, and Pandya clans, the Pallava dynasty, and the later Vijayanagara Empire, all of which shaped the state's cuisine, culture, and architecture. After the fall of the Kingdom of Mysore, the British colonised the region and administered it as part of the Madras Presidency, headquartered at the city of Madras, now known as Chennai. After India's Independence in 1947, the Madras State came into existence, whose borders were linguistically redrawn by the States Reorganisation Act, 1956, losing territory to Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. The state was renamed as Tamil Nadu in 1969. It is home to a number of historic buildings, multi-religious pilgrimage sites, hill stations and three World Heritage Sites.[7][8][9]

The economy of Tamil Nadu is the second-largest in India, with a gross state domestic product (GSDP) of ₹24.85 lakh crore (US$310 billion) and has the country's 11th-highest GSDP per capita of ₹225,106 (US$2,800).[3] It ranks 11th among all Indian states in human development index.[5] Tamil Nadu is the most urbanised state in India, and one of the most industrialised states; the manufacturing sector accounts for more than one-third of the state's GDP.[10] Its tourism industry is the largest among the Indian states. The Tamil film industry plays an influential role in the state's popular culture.

History

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence points to this area being one of the longest continuous habitations in the Indian peninsula.[11] In Attirampakkam near Chennai, archaeologists from the Sharma Centre for Heritage Education excavated ancient stone tools which suggest that a humanlike population existed in the Tamil Nadu region somewhere around 1,000 years before homo sapiens arrived from Africa.[12][13] A Neolithic stone celt (a hand-held axe) with the Indus script on it was discovered at Sembian-Kandiyur near Mayiladuthurai in Tamil Nadu. According to epigraphist Iravatham Mahadevan, this was the first datable artefact bearing the Indus script to be found in Tamil Nadu. According to Mahadevan, the find was evidence of the use of the Harappan language, and therefore that the "Neolithic people of the Tamil country spoke a Harappan language". The date of the celt was estimated at between 1500 BCE and 2000 BCE.[14][15][16] In Adichanallur, 24 km (15 mi) from Tirunelveli, archaeologists from the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) unearthed 169 clay urns containing human skulls, skeletons, bones, husks, grains of rice, charred rice, and celts of the Neolithic period, 3,800 years ago.[17] The ASI archaeologists have proposed that the script used at that site, Tamil Brahmi, is "very rudimentary" and date it somewhere between the 5th century BCE and 3rd century BCE.[18][19] About 60 per cent of the total epigraphical inscriptions found by the ASI in India are from Tamil Nadu, and most of these are in the Tamil language.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27] In Keezhadi near Madurai, excavations have revealed a large urban settlement dating to the 6th century BCE, during the time of urbanisation in the Gangetic plain. During this dig, some potsherds were uncovered with a script similar to Indus script, leading some to conclude it was a transition between the Indus Valley script and Tamil Brahmi script used in the Sangam period.[28]

Sangam period (500 BCE–300 CE)

The early history of the people and rulers of Tamil Nadu is a topic in Tamil literary sources known as Sangam literature. Numismatic, archaeological and literary sources corroborate that the Sangam period lasted for about eight centuries, from 500 BCE to 300 CE. The recent excavations in Alagankulam archaeological site suggests that Alagankulam is one of the important trade centers or port cities of the Sangam Era.[30]

Ancient Tamil Nadu contained three monarchical states, headed by kings called Vendhar and several tribal chieftaincies, headed by the chiefs called by the general denomination Vel or Velir. Still lower at the local level there were clan chiefs called kizhar or mannar.[31] The kings were known as the Moovendar, the three crowned kings, and were the Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas. The Cheras controlled the western part of Tamilkam, what is today western Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The Pandyas controlled the south, what is today southern Tamil Nadu. The Cholas had their base in the Kaveri delta and controlled what is today northern Tamil Nadu. Although these dynasties were never conquered by outside powers, there were still significant diplomatic contacts between them and kingdoms to the north. They were mentioned on the pillars of Ashoka.[32]

These rulers sponsored some of the earliest Tamil literature. The oldest Sangam work we have knowledge of is the Tolkappiyam, a book of Tamil grammar. Most Sangam literature dealt with themes of love and war. In these poems, a glimpse of Tamil society at the time can be glimpsed. The land was fertile, and people pursued different occupations depending on what regions they were in. Their gods included figures such as Seyyon and Kotravai, who were worshipped at different places.[33] The rulers patronised Buddhism and Jainism, and starting in the CE period references to Vedic customs begin to grow.[34]

Significant trade was also undertaken with the outside world. Much commerce from the Romans and Han China converged in the Tamil region, and the seaports of Muziris and Korkai were very popular destinations.[35] One of the most prized goods from Tamilkam was spices such as black pepper, but other spices, pearls and silk were also widely traded there.[36]

Starting in 300, however, there was a significant drop in Sangam literature. Some have attributed this to the Kalabhras, a dynasty which conquered much of Tamilkam during that time. Historians have speculated these rulers were antagonistic towards the astika schools which were dominant in later centuries, which is why later texts always portray their rule in a bad light, if at all.[37] During their rule, Samanar traditions greatly impacted literature written during this time. Literacy was widespread and epics such as the Cilappatikaram were written. The most prominent of these works is the Tirukkuṟaḷ written by Valluvar, a collection of couplets covering all aspects of life from ethics to love. This text is still treated with great reverence by those in the present-day.[38] Around the 7th century CE, the Kalabhras were overthrown by the Pandyas and Cholas,[39] who continued to patronise Buddhists and Jains before the Saiva and Vaishnava revivalism in the Bhakti movement.[40]

Middle Kingdoms (600–1300 CE)

Kallanai or Grand Anicut, an ancient dam built on the Kaveri River in Thanjavur district by Karikala Chola around the 2nd century CE[41][42][43][44]

Kallanai or Grand Anicut, an ancient dam built on the Kaveri River in Thanjavur district by Karikala Chola around the 2nd century CE[41][42][43][44] Shore Temple built by the Pallavas at Mamallapuram during the 8th century, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Shore Temple built by the Pallavas at Mamallapuram during the 8th century, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.jpg.webp) Vettuvan Koil, the unfinished temple is believed to have been built during the 8th century by Pandyas in Kalugumalai, a panchayat town in Thoothukudi district.

Vettuvan Koil, the unfinished temple is believed to have been built during the 8th century by Pandyas in Kalugumalai, a panchayat town in Thoothukudi district.

During the 4th to 8th centuries, Tamil Nadu saw the rise of the Pallava dynasty under Mahendravarman I and his son Mamalla Narasimhavarman I.[45] The Pallavas ruled parts of South India with Kanchipuram as their capital. Tamil architecture reached its peak during Pallava rule. Narasimhavarman II built the Shore Temple which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Much later, the Pallavas were replaced by the Chola dynasty as the dominant kingdom in the 9th century and they in turn were replaced by the Pandyan Dynasty in the 13th century. The Pandyan capital Madurai was in the deep south away from the coast. They had extensive trade links with the southeast Asian maritime empires of Srivijaya and their successors, as well as contacts, even formal diplomatic contacts, reaching as far as the Roman Empire. During the 13th century, Marco Polo mentioned the Pandyas as the richest empire in existence. Temples such as the Meenakshi Amman Temple at Madurai and Nellaiappar Temple at Tirunelveli are the best examples of Pandyan temple architecture.[46] The Pandyas excelled in both trade and literature. They controlled the pearl fisheries along the south coast of India, between Sri Lanka and India, which produced some of the finest pearls in the known ancient world.

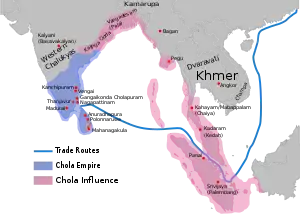

Chola Empire

During the 9th century, the Chola dynasty was once again revived by Vijayalaya Chola, who established Thanjavur as Chola's new capital by conquering central Tamil Nadu from Mutharaiyar and the Pandya King Varagunavarman II. Aditya I and his son Parantaka I expanded the kingdom to the northern parts of Tamil Nadu by defeating the last Pallava king, Aparajitavarman. Parantaka Chola II expanded the Chola empire into what is now interior Andhra Pradesh and coastal Karnataka, while under the great Rajaraja Chola and his son Rajendra Chola, the Cholas rose to a notable power in southeast Asia. Now the Chola Empire stretched as far as Bengal and Sri Lanka. At its peak, the empire spanned almost 3,600,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi). Rajaraja Chola conquered all of peninsular South India and parts of Sri Lanka. Rajendra Chola's navy went even further, occupying coasts from Burma (now) to Vietnam, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep, Sumatra, Java, Malaya, Philippines[47] in South East Asia and Pegu islands. He defeated Mahipala, the king of Bengal, and to commemorate his victory he built a new capital and named it Gangaikonda Cholapuram.

The Cholas were prolific temple builders right from the times of the first medieval King Vijayalaya Chola. These are the earliest specimen of Dravidian temples under the Cholas. His son Aditya I built several temples around the Kanchi and Kumbakonam regions. The Cholas went on to becoming a great power and built some of the most imposing religious structures in their lifetime and they also renovated temples and buildings of the Pallavas, acknowledging their common socio-religious and cultural heritage. The celebrated Nataraja temple at Chidambaram and the Ranganathaswamy Temple at Srirangam, Tiruchirappalli, held special significance for the Cholas which have been mentioned in their inscriptions as their tutelary deities. Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola built temples such as the Brihadeshvara Temple of Thanjavur and Brihadeshvara Temple of Gangaikonda Cholapuram, the Airavatesvara Temple of Darasuram and the Sarabeswara (Shiva) Temple, also called the Kampahareswarar Temple at Thirubhuvanam, the last two temples being located near Kumbakonam. The first three of the above four temples are titled Great Living Chola Temples among the UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

- Great Living Chola Temples

The granite gopuram (tower) of Brihadisvara Temple, 1010 CE

The granite gopuram (tower) of Brihadisvara Temple, 1010 CE Airavatesvara Temple built by Rajaraja Chola II in the 12th century CE

Airavatesvara Temple built by Rajaraja Chola II in the 12th century CE The pyramidal structure above the sanctum at Brihadisvara Temple, Gangaikonda Cholapuram

The pyramidal structure above the sanctum at Brihadisvara Temple, Gangaikonda Cholapuram Brihadisvara Temple Entrance Gopurams at Thanjavur

Brihadisvara Temple Entrance Gopurams at Thanjavur

Vijayanagar and Nayak period (1336–1646)

The Muslim invasions of southern India triggered the establishment of the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire with Vijayanagara in modern Karnataka as its capital. The Vijayanagara empire eventually conquered the entire Tamil country by c. 1370 and ruled for almost two centuries until its defeat in the Battle of Talikota in 1565 by a confederacy of Deccan sultanates. Subsequently, as the Vijayanagara Empire went into decline after the mid-16th century, many local rulers, called Nayaks, succeeded in gaining the trappings of independence. This eventually resulted in the further weakening of the empire; many Nayaks declared themselves independent, among whom the Nayaks of Madurai and Tanjore were the first to declare their independence, despite initially maintaining loose links with the Vijayanagara kingdom.[46] The Nayaks of Madurai and Nayaks of Thanjavur were the most prominent Nayaks of the 17th century. They reconstructed some of the well-known temples in Tamil Nadu such as the Meenakshi Temple.

Power struggles of the 18th century (1688–1802)

By the early 18th century, the political scene in Tamil Nadu saw a major change-over and was under the control of many minor rulers aspiring to be independent. The fall of the Vijayanagara empire and the Chandragiri Nayakas gave the sultanate of Golconda a chance to expand into the Tamil heartland. When the sultanate was incorporated into the Mughal Empire in 1688, the northern part of current-day Tamil Nadu was administrated by the Nawab of the Carnatic, who had his seat in Arcot from 1715 onward. Meanwhile, to the south, the fall of the Thanjavur Nayaks led to a short-lived Thanjavur Maratha kingdom. The fall of the Madurai Nayaks brought up many small Nayakars of southern Tamil Nadu, who ruled small parcels of land called Palayams. The chieftains of these Palayams were known as Palaiyakkarar (or 'polygar' as called by British) and were ruling under the nawabs of the Carnatic.

Europeans started to establish trade centers during the 17th century in the eastern coastal regions. Around 1609, the Dutch established a settlement in Pulicat,[48] while the Danes had their establishment in Tharangambadi also known as Tranquebar.[49] In 1639, the British, under the East India Company, established a settlement further south of Pulicat, in present-day Chennai. British constructed Fort St. George[50] and established a trading post at Madras.[51] The office of mayoralty of Madras was established in 1688. The French established trading posts at Pondichéry by 1693. The British and French were competing to expand the trade in the northern parts of Tamil Nadu which also witnessed many battles like Battle of Wandiwash as part of the Seven Years' War.[52] British reduced the French dominions in India to Puducherry. Nawabs of the Carnatic bestowed tax revenue collection rights on the East India Company for defeating the Kingdom of Mysore. Muhammad Ali Khan Wallajah surrendered much of his territory to the East India Company which firmly established the British in the northern parts. In 1762, a tripartite treaty was signed between Thanjavur Maratha, Carnatic, and the British by which Thanjavur became a vassal of the Nawab of the Carnatic which eventually ceded to the British.

In the south, Nawabs granted taxation rights to the British which led to conflicts between British and the Palaiyakkarar, which resulted in series of wars called Polygar war to establish independent states by the aspiring Palaiyakkarar. Puli Thevar was one of the earliest opponents of the British rule in South India.[53] Thevar's prominent exploits were his confrontations with Marudhanayagam, who later rebelled against the British in the late 1750s and early 1760s. Rani Velu Nachiyar, was the first woman freedom fighter of India and Queen of Sivagangai.[54] She was drawn to war after her husband Muthu Vaduganatha Thevar (1750–1772), King of Sivaganga was murdered at Kalayar Kovil temple by British. Before her death, Queen Velu Nachi granted powers to the Maruthu brothers to rule Sivaganga.[55] Kattabomman (1760–1799), Palaiyakkara chief of Panchalakurichi who fought the British in the First Polygar War.[56] He was captured by the British at the end of the war and hanged near Kayattar in 1799. Veeran Sundaralingam (1700–1800) was the General of Kattabomman Nayakan's palayam, who died in the process of blowing up a British ammunition dump in 1799 which killed more than 150 British soldiers to save Kattapomman Palace. Oomaithurai, younger brother of Kattabomman, took asylum under the Maruthu brothers, Periya Marudhu and Chinna Marudhu and raised an army.[57] They formed a coalition with Dheeran Chinnamalai and Kerala Varma Pazhassi Raja, which fought the British in Second Polygar Wars. Dheeran Chinnamalai (1756–1805), Polygar chieftain of Kongu and ally of Tipu Sultan who fought the British in the Second Polygar War. After winning the Polygar wars in 1801, the East India Company consolidated most of southern India into the Madras Presidency.

The Pudukkottai Thondaimans rose to power over the Pudukkottai area by the end of the 17th Century. The Pudukkottai kingdom has the distinction of being the only princely state in Tamil Nadu, and only became part of the Indian union in 1948 after independence.[58]

Vellore Mutiny and Indian Rebellion (1801–1947 CE)

At the beginning of the 19th century, the British firmly established governance over the entirety of Tamil Nadu. The Vellore mutiny on 10 July 1806 was the first instance of a large-scale mutiny by Indian sepoys against the British East India Company, predating the Indian Rebellion of 1857 by half a century.[59] The revolt, which took place in Vellore, was brief, lasting one full day, but brutal as mutineers broke into the Vellore fort and killed or wounded 200 British troops, before they were subdued by reinforcements from nearby Arcot.[60][61]

The British Raj was formed after the British crown took over the control governance from the company and the remainder of the 19th century did not witness any native resistance until the beginning of 20th century Indian Independence movement. During the administration of Governor George Harris (1854–1859) measures were taken to improve education and increase the representation of Indians in the administration. Legislative powers are given to the Governor's council under the Indian Councils Act 1861 and 1909 Minto-Morley Reforms eventually led to the establishment of the Madras Legislative Council. Failure of the summer monsoons and administrative shortcomings of the Ryotwari system resulted in two severe famines in the Madras Presidency, the Great Famine of 1876–78 and the Indian famine of 1896–97 killed millions of Tamils.[62] The famine led to the migration of many Tamil peasants as bonded labourers for the British to countries like Malaysia and Mauritius, which eventually formed the present Tamil diaspora.

Tamil Nadu provided a significant number of freedom fighters to the Independence struggle such as V. O. Chidambaram Pillai and Bharatiyar.[63] The Tamils (particularly Tamil Malaysians) formed a significant percentage of the members of the Indian National Army (INA), founded by Subhas Chandra Bose to fight the British colonial rule in India.[64][65] Lakshmi Sahgal from Tamil Nadu was a prominent leader in the INA's Rani of Jhansi Regiment.

In 1916 Dr. T.M. Nair and Rao Bahadur Thygaraya Chetty released the Non-Brahmin Manifesto[66] and helped to form the Justice Party, an organisation that sought to reduce Brahmin domination of the civil service. The party won the legislative assembly elections of 1921, which was boycotted by the Congress. This party implemented reservations in government jobs and education for non-Brahmins in 1926, and stayed in power for 13 years. The other main movement was the self-respect movement of E. V. Ramaswamy, better known as Periyar. Periyar campaigned for an end to what he saw as Aryan domination of culture and life in Tamil Nadu. To this end, he became an advocate of rationalism, and campaigned against the caste system, religion, and superstition.[66]

Further steps towards eventual self-rule were taken in 1935 when the British Government passed the Government of India Act 1935. Fresh local elections were held and in Tamil Nadu the Congress party captured power defeating the Justice party. In 1938, Periyar along with C. N. Annadurai launched an agitation against the Congress ministry's decision to introduce the teaching of Hindi in schools. Thereafter, the Justice party was taken over by Periyar who renamed it Dravidar Kazhagam and took it out of electoral politics. The group became an advocate for a separate Dravida Nadu (lit. land of the Dravidians) during discussions of the partition of India.[67]

Post-Independence (1947–present)

When India became independent in 1947, Madras presidency became Madras State, comprising present-day Tamil Nadu and coastal Andhra Pradesh, South Canara district of Karnataka, and parts of Kerala. The state was subsequently split up along linguistic lines. In 1969, Madras State was renamed Tamil Nadu, meaning "Tamil country".[68]

Geography

Tamil Nadu covers an area of 130,058 km2 (50,216 sq mi) , and is the tenth-largest state in India. The bordering states are Kerala to the west, Karnataka to the north-west and Andhra Pradesh to the north. To the east is the Bay of Bengal and the state encircles the union territory of Puducherry. The southernmost tip of the Indian Peninsula is Kanyakumari which is the meeting point of the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and the Indian Ocean.

The western, southern, and the northwestern parts are hilly and rich in vegetation. The Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats meet at the Nilgiri Hills. The Western Ghats traverse the entire western border with Kerala, effectively blocking much of the rain-bearing clouds of the south-west monsoon from entering the state. The eastern parts are fertile coastal plains and the northern parts are a mix of hills and plains. The central and the south-central regions are arid plains and receive less rainfall than the other regions.

Tamil Nadu has the country's third-longest coastline at about 906.9 km (563.5 mi).[69] Pamban Island and a group of smaller limestone shoals make up the northern portion of Ram Setu, which was formerly a natural bridge linking India with Sri Lanka. Tamil Nadu's coastline bore the brunt of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami when it hit India, which caused 7,793 direct deaths in the state. Tamil Nadu falls mostly in a region of low seismic hazard with the exception of the western border areas that lie in a low to moderate hazard zone; as per the 2002 Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) map, Tamil Nadu falls in Zones II and III. Historically, parts of this region have experienced seismic activity in the M5.0 range.[70]

Climate

Tamil Nadu is mostly dependent on monsoon rains and thereby is prone to droughts when the monsoons fail. The climate of the state ranges from dry sub-humid to semi-arid. The state has two distinct periods of rainfall:

- South west monsoon from June to September, with strong southwest winds;

- North east monsoon from October to December, with dominant northeast winds;

The annual rainfall of the state is about 945 mm (37.2 in) of which 48 per cent is through the northeast monsoon, and 32 per cent through the southwest monsoon. Since the state is entirely dependent on rains for recharging its water resources, monsoon failures lead to acute water scarcity and severe drought.[71] Tamil Nadu is divided into seven agro-climatic zones: northeast, northwest, west, southern, high rainfall, high altitude hilly, and Kaveri Delta (the most fertile agricultural zone).

Flora and fauna

There are about 2,000 species of wildlife that are native to Tamil Nadu. Protected areas provide safe habitat for large mammals including elephants, tigers, leopards, wild dogs, sloth bears, gaurs, lion-tailed macaques, Nilgiri langurs, Nilgiri tahrs, grizzled giant squirrels and sambar deer, resident and migratory birds such as cormorants, darters, herons, egrets, open-billed storks, spoonbills and white ibises, little grebes, Indian moorhen, black-winged stilts, a few migratory ducks and occasionally grey pelicans, marine species such as the dugongs, turtles, dolphins, Balanoglossus and a wide variety of fish and insects.

Indian Angiosperm diversity comprises 17,672 species with Tamil Nadu leading all states in the country, with 5640 species accounting for 1/3 of the total flora of India. This includes 1,559 species of medicinal plants, 533 endemic species, 260 species of wild relatives of cultivated plants and 230 red-listed species. The gymnosperm diversity of the country is 64 species of which Tamil Nadu has four indigenous species and about 60 introduced species. The Pteridophytes diversity of India includes 1,022 species of which Tamil Nadu has about 184 species. Vast numbers of bryophytes, lichen, fungi, algae, and bacteria are among the wild plant diversity of Tamil Nadu.

Common plant species include the state tree: palmyra palm, eucalyptus, rubber, cinchona, clumping bamboos (Bambusa arundinacea), common teak, Anogeissus latifolia, Indian laurel, grewia, and blooming trees like Indian laburnum, ardisia, and solanaceae. Rare and unique plant life includes Combretum ovalifolium, ebony (Diospyros nilagrica), Habenaria rariflora (orchid), Alsophila, Impatiens elegans, Ranunculus reniformis, and royal fern.[72]

National and state parks

Tamil Nadu has a wide range of biomes extending east from the South Western Ghats montane rain forests in the Western Ghats through the South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests and Deccan thorn scrub forests to tropical dry broadleaf forests and then to the beaches, estuaries, salt marshes, mangroves, seagrasses and coral reefs of the Bay of Bengal. The state has a range of flora and fauna with many species and habitats. To protect this diversity of wildlife there are Protected areas of Tamil Nadu as well as biospheres which protect larger areas of natural habitat often include one or more national parks. The Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve established in 1986 is a marine ecosystem with seaweed seagrass communities, coral reefs, salt marshes, and mangrove forests. The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve located in the Western Ghats and Nilgiri Hills comprises part of adjoining states of Kerala and Karnataka. The Agasthyamala Biosphere Reserve is in the southwest of the state bordering Kerala in the Western Ghats. Tamil Nadu is home to five declared national parks located in Anamalai, Mudumalai, Mukurthi, Gulf of Mannar, Guindy located in the center of Chennai City and Vandalur located in South Chennai. Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve, Mukurthi National Park and Kalakkad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve are the tiger reserves in the state.

Governance and administration

The governor is the constitutional head of the state while the chief minister is the head of the government and the head of the council of ministers.[73] The Chief Justice of the Madras High Court is the head of the judiciary.[73] The present governor, chief minister and the chief justice are R. N. Ravi,[74] M. K. Stalin[75] and Munishwar Nath Bhandari[76] respectively. Administratively the state is divided into 38 districts. Chennai, the capital of the state is the fourth largest urban agglomeration in India and is also one of the major metropolitan cities of India. The state comprises 39 Lok Sabha constituencies and 234 Legislative Assembly constituencies.[77]

Tamil Nadu had a bicameral legislature until 1986, when it was replaced with a unicameral legislature, like most other states in India. The term length of the government is five years. The present government is headed by M.K.Stalin of the DMK (Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam) party after his recent victory in the Tamil Nadu Legislative Elections in 2021 . The Tamil Nadu legislative assembly is housed at the Fort St. George in Chennai. The state had come under the President's rule on four occasions – first from 1976 to 1977, next for a short period in 1980, then from 1988 to 1989 and the latest in 1991.

Tamil Nadu has been a pioneering state of E-Governance initiatives in India. A large part of the government records like land ownership records are digitised and all major offices of the state government like Urban Local Bodies – all the corporations and municipal office activities – revenue collection, land registration offices, and transport offices have been computerised. Tamil Nadu is one of the states where law and order have been maintained largely successfully.[78] The Tamil Nadu Police Force is over 140 years old. It is the fifth-largest state police force in India (as of 2015, total police force of TN is 1,11,448) and has the highest proportion of women police personnel in the country (total women police personnel of TN is 13,842 which is about 12.42%) to specifically handled violence against women in Tamil Nadu.[79][80] In 2003, the state had a total police population ratio of 1:668, higher than the national average of 1:717.

Administrative subdivisions

Tamil Nadu is divided into four major divisions as per the ancient Tamil kings namely Pallava Nadu division, Chera Nadu division, Chola Nadu division and Pandya Nadu division and the four divisions are further subdivided into 38 districts, which are listed below. A district is administered by a District Collector who is mostly an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) member, appointed by State Government. Districts are further divided into 226 Taluks administrated by Tahsildars comprising 1127 Revenue blocks administrated by Revenue Inspector (RI). A District also has one or more Revenue Divisions (in total 76) administrated by Revenue Divisional Officer (RDO), constituted by many Revenue Blocks. 16,564 Revenue villages (Village Panchayat) are the primary grassroots level administrative units which in turn might include many villages and administered by a Village Administrative Officer (VAO), many of which form a Revenue Block. Cities and towns are administered by Municipal corporations and Municipalities respectively. The urban bodies include 15 city corporations, 152 municipalities and 529 town panchayats.[81][82][83] The rural bodies include 31 district panchayats, 385 panchayat unions and 12,524 village panchayats.[84][85][86]

Cities and towns

The state capital of Chennai is the most populous city in the state with more than 8,900,000 residents, followed by Coimbatore, Madurai, Trichy and Salem, respectively.[87][88] Chennai is also the sixth-most populous city in India according to the 2011 Indian census.

Largest cities or towns in Tamil Nadu As of the 2011 Census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||||||

Chennai  Coimbatore |

1 | Chennai | Chennai | 8,696,010 |  Madurai  Tiruchirappalli | ||||

| 2 | Coimbatore | Coimbatore | 2,151,466 | ||||||

| 3 | Madurai | Madurai | 1,462,420 | ||||||

| 4 | Tiruchirappalli | Tiruchirappalli | 1,021,717 | ||||||

| 5 | Tiruppur | Tiruppur | 962,982 | ||||||

| 6 | Salem | Salem | 919,150 | ||||||

| 7 | Erode | Erode | 521,776 | ||||||

| 8 | Vellore | Vellore | 504,079 | ||||||

| 9 | Tirunelveli | Tirunelveli | 498,984 | ||||||

| 10 | Thoothukudi | Thoothukudi | 410,760 | ||||||

Politics

Pre-Independence

Prior to Indian independence, Tamil Nadu was under British colonial rule as part of the Madras Presidency. The main party in Tamil Nadu at that time was the Indian National Congress (INC). Regional parties have dominated state politics since 1916. One of the earliest regional parties, the South Indian Welfare Association, a forerunner to Dravidian parties in Tamil Nadu, was started in 1916. The party was called after its English organ, Justice Party, by its opponents. Later, South Indian Liberal Federation was adopted as its official name. The reason for the victory of the Justice Party in elections was the non-participation of the INC, demanding complete independence of India.

The Justice Party which was under E. V. Ramasamy was renamed Dravidar Kazhagam in 1944. It was a non-political party which demanded the establishment of an independent state called Dravida Nadu. However, due to the differences between its two leaders E. V. Ramasamy and C. N. Annadurai, the party was split.

Post-Independence

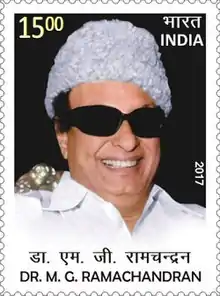

C. N. Annadurai left the party Dravida Kazhagam to form the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). The DMK decided to enter politics in 1956. After the demise of C. N. Annadurai, M. Karunanidhi became the leader of the party which was supported by majority leaders including then famous actor M. G. Ramachandran. As a breakaway faction of the DMK, in 1972, M. G. Ramachandran founded the new Dravidian party All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) named after his political mentor C. N. Annadurai popularly called "Anna". After the demise of M. G. Ramachandran, J. Jayalalithaa succeeded the leadership of the AIADMK party and was fondly called Amma (The Mother) by millions.[89]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 30,119,000 | — |

| 1961 | 33,687,000 | +11.8% |

| 1971 | 41,199,000 | +22.3% |

| 1981 | 48,408,000 | +17.5% |

| 1991 | 55,859,000 | +15.4% |

| 2001 | 62,406,000 | +11.7% |

| 2011 | 72,138,958 | +15.6% |

| Source:Census of India[90] | ||

Tamil Nadu is the seventh most populous state in India. 48.4 per cent of the state's population lives in urban areas, the third-highest percentage among large states in India. The state has registered the lowest fertility rate in India in the year 2005–06 with 1.7 children born for each woman, lower than required for population sustainability.[91][92]

At the 2011 India census, Tamil Nadu had a population of 72,147,030.[93] The sex ratio of the state is 995 with 36,137,975 males and 36,009,055 females. There are a total of 23,166,721 households.[93] The total children under the age of 6 is 7,423,832. A total of 14,438,445 people constituting 20.01 per cent of the total population belonged to Scheduled Castes (SC) and 794,697 people constituting 1.10 per cent of the population belonged to Scheduled tribes (ST).[93][94]

The state has 51,837,507 literates, making the literacy rate 80.33 per cent. There are a total of 27,878,282 workers, comprising 4,738,819 cultivators, 6,062,786 agricultural labourers, 1,261,059 in house hold industries, 11,695,119 other workers, 4,120,499 marginal workers, 377,220 marginal cultivators, 2,574,844 marginal agricultural labourers, 238,702 marginal workers in household industries and 929,733 other marginal workers.[95]

India has a human development index calculated as 0.619, while the corresponding figure for Tamil Nadu is 0.736, placing it among the top states in the country.[96][97] The life expectancy at birth for males is 65.2 years and for females it is 67.6 years.[98] However, it has a high level of poverty, especially in rural areas. In 2004–2005, the poverty line was set at ₹351.86/month for rural areas and ₹547.42/month for urban areas. Poverty in the state dropped from 51.7 per cent in 1983 to 21.1 per cent in 2001.[99] For the period 2004–2005, the Trend in Incidence of Poverty in the state was 22.5 per cent compared with the national figure of 27.5 per cent. The World Bank is currently assisting the state in reducing poverty, high drop-out and low completion of secondary schools continue to hinder the quality of training in the population. Other problems include class, gender, inter-district, and urban-rural disparities. Based on URP – Consumption for the period 2004–2005, the percentage of the state's population below the poverty line was 27.5 per cent. The Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative ranks Tamil Nadu to have a Multidimensional Poverty Index of 0.141, which is in the level of Ghana among the developing countries.[100] Corruption is a major problem in the state with Transparency International ranking it the second most corrupt among the states of India.[101]

Religion

According to the 2011 census, Hinduism is followed by the majority of the population of Tamil Nadu, around 88 percent. Christians are the largest religious minority in the state, at around 6.12 percent of the population, followed by Islam at 5.86 percent.[103]

Language

Tamil is the sole official language of Tamil Nadu, while English has been declared as the additional official language by the Government of Tamil Nadu.[4] When India adopted national standards, Tamil language was the first to be recognised as a classical language of India.[104] As of 2011 census report, Tamil is spoken as the first language by 88.35 percent of the state's population, followed by Telugu (5.87%), Kannada (1.58%), Urdu (1.75%), Malayalam (1%) and other languages (1.53%).[105]

LGBT rights

The Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights in Tamil Nadu are among the most progressive in India.[107][108] Chennai Rainbow Pride has been held in the Capital city of Chennai annually since 2009.[109] Tamil Nadu is also the first Indian state to ban conversion therapy, following the Madras High Court.[110] Tamil Nadu was the first Indian state to introduce a transgender welfare policy, wherein transgender people can avail free sex reassignment surgery in government hospitals. The state was also the first to ban forced sex-selective surgeries on intersex infants.[111][112]

In 2019, the Madras High Court ruled that the term "bride" under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 includes trans women and thereby legalising marriage between a man and a transgender woman.[113]

Education

Tamil Nadu is one of the most literate states in India.[114] Tamil Nadu has performed reasonably well in terms of literacy growth during the decade 2001–2011. A survey conducted by the industry body Assocham ranks Tamil Nadu top among Indian states with about 100 per cent gross enrolment ratio (GER) in primary and upper primary education. One of the basic limitations for improvement in education in the state is the rate of absence of teachers in public schools, which at 21.4 per cent is significant.[115] The analysis of primary school education in the state by Pratham shows a low drop-off rate but the poor quality of state education compared to other states.[116] Tamil Nadu has 37 universities, 552 engineering colleges[117] 449 polytechnic colleges[118] and 566 arts and science colleges, 34,335 elementary schools, 5,167 high schools, 5,054 higher secondary schools and 5,000 hospitals. Some of the notable educational institutes present in Tamil Nadu are Indian Institute of Technology Madras, University of Madras, Anna University, National Institute of Technology, Tiruchirappalli, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Indian Institute of Information Technology, Design and Manufacturing, Kancheepuram, Vellore Institute of Technology, Indian Institute of Management Tiruchirappalli, Annamalai University (Chidambaram), Loyola College, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Presidency College, Chennai, College of Engineering, Guindy, Madras Institute of Technology, PSG College of Technology, Coimbatore Institute of Technology, Government College of Technology, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu Dr. Ambedkar Law University, Tamil Nadu National Law University, Government Law College, Coimbatore, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Madras Medical College, Stanley Medical College, Madras Veterinary College, Coimbatore Medical College and Institute of Road and Transport Technology.

Tamil Nadu now has 69 per cent reservation in educational institutions for socially backward sections of society, the highest among all Indian states.[119] The Midday Meal Scheme programme in Tamil Nadu was first initiated by Kamaraj, then it was expanded by M G Ramachandran in 1983.

Economy

| Year | GSDP | Growth Rate | Share in India |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–01 | 1,420,650 | 5.87% | 7.62% |

| 2001–02 | 1,398,420 | −1.56% | 7.09% |

| 2002–03 | 1,422,950 | 1.75% | 6.95% |

| 2003–04 | 1,508,150 | 5.99% | 6.79% |

| 2004–05 | 2,190,030 | 11.45% | 7.37% |

| 2005–06 | 2,495,670 | 13.96% | 7.67% |

| 2006–07 | 2,875,300 | 15.21% | 8.07% |

| 2007–08 | 3,051,570 | 6.13% | 7.83% |

| 2008–09 | 3,217,930 | 5.45% | 7.74% |

| 2009–10 | 3,566,320 | 10.83% | 7.89% |

| 2010–11 | 4,034,160 | 13.12% | 8.20% |

| 2011–12 | 4,332,380 | 7.39% | 8.26% |

| 2012–13 | 4,479,440 | 3.39% | 8.17% |

| 2013–14 | 4,806,180 | 7.29% | 8.37% |

For the year 2014–15 Tamil Nadu's GSDP was ₹9.767 trillion (US$120 billion), and growth was 14.86.[121] It ranks third in foreign direct investment (FDI) approvals (cumulative 1991–2002) of ₹225.826 billion ($5,000 million), next only to Maharashtra and Delhi constituting 9.12 per cent of the total FDI in the country.[122] The per capita income in 2007–2008 for the state was ₹72,993 ranking third among states with a population over 10 million and has steadily been above the national average.[123]

According to the 2011 Census, Tamil Nadu is the most urbanised state in India (49 per cent), accounting for 9.6 per cent of the urban population while only comprising 6 per cent of India's total population.[124][125] Services contribute to 45 per cent of the economic activity in the state, followed by manufacturing at 34 per cent and agriculture at 21 per cent. The government is the major investor in the state with 51 per cent of total investments, followed by private Indian investors at 29.9 per cent and foreign private investors at 14.9 per cent. Tamil Nadu has a network of about 113 industrial parks and estates offering developed plots with supporting infrastructure. According to the publications of the Tamil Nadu government, the Gross State Domestic Product at Constant Prices (The base year 2004–2005) for the year 2011–2012 is ₹4.281 trillion (US$54 billion), an increase of 9.39 per cent over the previous year. The per capita income at the current price is ₹72,993.

Tamil Nadu has six Nationalized Home Banks which originated in this state; Two government-sector banks Indian Bank and Indian Overseas Bank in Chennai, and four private-sector banks City Union Bank in Kumbakonam, Karur Vysya Bank, Lakshmi Vilas Bank in Karur, and Tamilnad Mercantile Bank Limited in Tuticorin.

Agriculture

Tamil Nadu has historically been an agricultural state and is a leading producer of agricultural products in India. In 2008, Tamil Nadu was India's fifth biggest producer of rice. The total cultivated area in the state was 5.60 million hectares in 2009–10.[126] The Cauvery delta region is known as the Rice Bowl of Tamil Nadu.[127] In terms of production, Tamil Nadu accounts for 10 per cent in fruits and 6 per cent in vegetables, in India.[128] Annual food grains production in the year 2007–08 was 10035,000 mt.[126]

The state is the largest producer of bananas, turmeric, flowers,[128] tapioca,[128] the second largest producer of mango,[128] natural rubber,[129] coconut, groundnut and the third largest producer of coffee, sapota,[128] tea[130] and sugarcane. Tamil Nadu's sugarcane yield per hectare is the highest in India. The state has 17,000 hectares of land under oil palm cultivation, the second highest in India.[131]

Dr. M.S. Swaminathan, known as the "father of the Indian Green Revolution" was from Tamil Nadu.[132] Tamil Nadu Agricultural University with its seven colleges and thirty-two research stations spread over the entire state contributes to evolving new crop varieties and technologies and disseminating through various extension agencies. Among states in India, Tamil Nadu is one of the leaders in livestock, poultry, and fisheries production. Tamil Nadu had the second largest number of poultry amongst all the states and accounted for 17.7 per cent of the total poultry population in India.[133] In 2003–2004, Tamil Nadu had produced 3783.6 million of eggs, which was the second-highest in India representing 9.37 per cent of the total egg production in the country.[134] With the second-longest coastline in India, Tamil Nadu represented 27.54 per cent of the total value of fish and fishery products exported by India in 2006. Namakkal is also one of the major centers of egg production in India. Oddanchatram is one of the major centers for vegetable supply in Tamil Nadu and is also known as the vegetable city of Tamil Nadu.Coimbatore is one of the major centers for poultry production.[135][136]

Textiles and leather

Tamil Nadu is one of the leading states in the textile sector and it houses the country's largest spinning industry accounting for almost 80 per cent of the total installed capacity in India. When it comes to yarn production, the State contributes 40 per cent of the total production in the country. There are 2,614 Hand Processing Units (25 per cent of total units in the country) and 985 Power Processing Units (40 per cent of total units in the country) in Tamil Nadu. According to official data, the textile industry in Tamil Nadu accounts for 17 per cent of the total invested capital in all the industries.[137] Coimbatore is often referred to as the "Manchester of South India" due to its cotton production and textile industries.[138] Tirupur is the country's largest exporter of knitwear.[139][140][141] for its cotton production.

Tamil Nadu accounts for 60 per cent of leather tanning capacity in India[142] and 38 per cent of all leather footwear, garments and components. The state also accounts for 50 per cent of leather exports[143][144] from India, valued at around US$3.3 billion of the total US$6.5 billion from India. Hundreds of leather and tannery facilities are located around Vellore and its nearby towns.

Automobiles

Tamil Nadu has seen major investments in the automobile industry over many decades manufacturing cars, railway coaches, battle-tanks, tractors, motorcycles, automobile spare parts and accessories, tyres and heavy vehicles. Chennai is known as the Detroit of India.[145] Major global automobile companies including BMW, Ford, Robert Bosch, Renault-Nissan, Caterpillar, Hyundai, Mitsubishi Motors, and Michelin as well as Indian automobile majors like Mahindra & Mahindra, Ashok Leyland, Eicher Motors, Isuzu Motors, TI cycles, Hindustan Motors, TVS Motors, Irizar-TVS, Royal Enfield, MRF, Apollo Tyres, TAFE Tractors, Daimler AG Company invested ₹4 billion for establishing a new plant in Tamil Nadu.[146]

Heavy industries and engineering

Tamil Nadu is one of the highly industrialised states in India. Over 11% of the S&P CNX 500 conglomerates have corporate offices in Tamil Nadu.[147]

The state government owns Tamil Nadu Newsprint and Papers, in Karur.[148]

Coimbatore is also referred to as "the Pump City" as it supplies two-thirds of India's requirements of motors and pumps. The city is one of the largest exporters of wet grinders and auto components and the term "Coimbatore Wet Grinder" has been given a Geographical indication.[149]

Electronics and software

Electronics manufacturing is a growing industry in Tamil Nadu, with many international companies like Nokia, Flex, Motorola, Sony-Ericsson, Foxconn, Samsung, Cisco, Moser Baer, Lenovo, Dell, Sanmina-SCI, Bosch, Texas Instruments having chosen Chennai as their South Asian manufacturing hub. Products manufactured include circuit boards and cellular phone handsets.[150]

Tamil Nadu is the second largest software exporter by value in India. Software exports from Tamil Nadu grew from ₹76 billion ($1.6 billion) in 2003–04 to ₹207 billion {$5 billion} by 2006–07 according to NASSCOM[151] and to ₹366 billion in 2008–09 which shows 29 per cent growth in software exports according to STPI. Major national and global IT companies such as Atos Syntel, Infosys, Wipro, HCL Technologies, Tata Consultancy Services, Verizon, Hewlett-Packard Enterprise, Amazon.com, Capgemini, CGI, PayPal, IBM, NTT DATA, Accenture, Ramco Systems, Robert Bosch GmbH, DXC Technology, Cognizant, Tech Mahindra, Virtusa, LTI, Mphasis, Mindtree, Zoho, Mywebbee, and many others have offices in Tamil Nadu. The top engineering colleges in Tamil Nadu have been a major recruiting hub for the IT firms. According to estimates, about 50 per cent of the human resources required for the IT and ITES industry was being sourced from the state.[152] Coimbatore is the second largest software producer in the state, next to Chennai.[153]

Chennai has emerged as the SaaS Capital of India.[154][155][156][157] The SaaS sector in/around Chennai generates US$1 billion in revenue and employs about 10000 personnel.[157]

Transportation

Tamil Nadu has a transportation system that connects all parts of the state, via highway roads, railway lines, airports, and seaports.

Road

The state is served by an extensive road network, providing links between urban centers, agricultural market-places and rural areas. There are 29 national highways in the state, covering a total distance of 5,006.14 km (3,110.67 mi).[158][159] The state is also a terminus for the Golden Quadrilateral project that connects Indian metropolises like (New Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chennai and Kolkata). The state has a total road length of 167,000 km (104,000 mi), of which 60,628 km (37,672 mi) are maintained by the Highways Department. This is nearly 2.5 times higher than the density of all-India road network.[160] The major road junctions are Chennai, Vellore, Madurai, Trichy, Coimbatore, Tiruppur, Salem, Tirunelveli, Thoothukudi, Karur, Kumbakonam, Krishnagiri, Dindigul and Kanniyakumari. Road transport is provided by state owned Tamil Nadu State Transport Corporation and State Express Transport Corporation. Almost every part of the state is well connected by buses 24 hours a day. The state accounted for 13.6 per cent of all accidents in the country with 66,238 accidents in 2013, 11.3 per cent of all road accident deaths and 15 per cent of all road-related injuries, according to data provided by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. Although Tamil Nadu accounts for the highest number of road accidents in India, it also leads in having reduced the number of fatalities in accident-prone areas with deployment of personnel and a sustained awareness campaign. The number of deaths at areas decreased from 1,053 in 2011 to 881 in 2012 and 867 in 2013.[161]

Rail

Tamil Nadu has a well-developed rail network as part of Southern Railway. Headquartered at Chennai, the Southern Railway network extends over a large area of India's southern peninsula, covering the states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry, a small portion of Karnataka and a small portion of Andhra Pradesh. Express trains connect the state capital Chennai with Mumbai, Delhi, and Kolkata. Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. M.G. Ramachandran Central Railway Station is the gateway for trains towards the north whereas Chennai Egmore serves as the gateway for the south. Tamil Nadu has a total railway track length of 5,952 km (3,698 mi) and there are 532 railway stations in the state. The network connects the state with most major cities in India. The Nilgiri Mountain Railway (part of the Mountain Railways of India) is one of the UNESCO World Heritage Site connecting Ooty on the hills and Mettupalayam in the foothills which is in turn connected to Coimbatore. The centenary old Pamban Bridge over sea connecting Rameswaram in Pamban island to the mainland is an engineering marvel. It is one of the oldest cantilever bridges still in operation, the double-leaf bascule bridge section can be raised to let boats and small ships pass through the Palk Strait in the Indian Ocean. The government of Tamil Nadu created a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) for implementing the Chennai Metro Rail Project. This SPV named as "Chennai Metro Rail Limited" was incorporated on 3 December 2007 under the Companies Act. It has now been converted into a joint venture of the governments of India and of Tamil Nadu with equal equity holding. Chennai has a well-established suburban railway network and is constructing a Chennai Metro with phase1 operational since July 2015. Major railway junctions (four and above lines) in the state are Chennai, Coimbatore, Katpadi, Madurai, Salem, Erode, Dindigul, Karur, Nagercoil, Tiruchirapalli, and Tirunelveli. Chennai Central, Chennai Egmore, Coimbatore Junction, Tiruchirappalli Junction, Madurai Junction, Salem Junction and Katpadi Junction are upgraded to A1 grade level. Loco sheds are located at Erode, Arakkonam, Royapuram in Chennai and Tondaiyarpet in Chennai, Ponmalai (GOC) in Tiruchirappalli as Diesel Loco Shed. The loco shed at Erode is a huge composite electric and diesel Loco shed. MRTS which covers from Chennai Beach to Velachery, and metro rails also running from Washermenpet to Airport metro station and Central metro station to St.Thomas Mount metro station.

Airports

Tamil Nadu has three international airports, namely Chennai International Airport, Coimbatore International Airport, Tiruchirappalli International Airport. Madurai Airport is the only customs airport in the state. Salem Airport, Tuticorin Airport and Vellore Airport are the domestic airports. Chennai International Airport is a major international airport and aviation hub in South Asia. Besides civilian airports, the state has three air bases of the Indian Air Force namely Sulur Air Force Station, Thanjavur Air Force Station and Tambaram Air Force Station and two naval air stations INS Rajali and INS Parundu of Indian Navy. Neyveli Airport is being renovated since 2019[162] to start the service from mid 2020.

Seaports

Tamil Nadu has three major seaports located at Chennai, Ennore and Thoothukkudi, as well as seven other minor ports including Cuddalore and Nagapattinam.[126] Chennai Port is an artificial harbour situated on the Coromandel Coast and is the second principal port in the country for handling containers. Ennore Port handles all the coal and ore traffic in Tamil Nadu. The volume of cargo in the ports grew by 13 per cent during 2005.[163]

Spaceport

In Tamil Nadu, the Government of India is to set up a new Rocket launch pad near Kulasekharapatnam in Thoothukudi district for which the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) has begun work. The location was selected because of its nearness to the equator like the Sriharikota spaceport in the Satish Dhawan Space Centre.[164]

Infrastructure

Communication

Tamil Nadu has four mobile service providers namely BSNL,[165] Airtel,[166] Jio[167] and Vi (Vodafone Idea).[168] BSNL provides 2G and 3G mobile internet connections; Airtel and Vi provide 2G, 3G and 4G services and Jio offers only 4G across Tamil Nadu. Airtel Broadband,[169] Act Broadband[170] BSNL, Hathway[171] and few others are providing high speed Fiber Optic broadband connection in many cities and rural areas across Tamil Nadu.

Tamil Nadu government is planning to lay 55,000 km of optical fibre cable across the state and provide high-speed internet up to 1 Gbit/s and connect all the corporations, municipalities, town panchayats and village panchayats. This infrastructure would also benefit all the government departments, entrepreneurs and individual homes.[172]

Energy

Tamil Nadu has the third largest installed power generation capacity in the country. The Kalpakkam Nuclear Power Plant, Ennore Thermal Plant, Neyveli Lignite Power Plant, many hydroelectric plants including Mettur Dam, hundreds of windmills and the Narimanam Natural Gas Plants are major sources of Tamil Nadu's electricity. The state generates a significant proportion of its power needs from renewable sources with wind power installed capacity at over 7154 MW,[173] accounting for 38 per cent of total installed wind power in India .[174] It is presently adding the Koodankulam Nuclear Power Plant to its energy grid, which on completion would be the largest atomic power plant in the country with 2000MW installed capacity.[175] The total installed capacity of electricity in the state by January 2014 was 20,716 MW.[176] Tamil Nadu ranks first nationwide in diesel-based thermal electricity generation with a national market share of over 34 per cent.[177] From a power surplus state in 2005–06, Tamil Nadu has become a state facing severe power shortage over the recent years due to lack of new power generation projects and delay in commercial power generation at Kudankulam Atomic Power Project. The Tuticorin Thermal Power Station has five 210 megawatt generators. The first generator was commissioned in July 1979. The thermal power plants under construction include the coal-based 1000 MW NLC TNEB Power Plant. From the current 17MW installed solar power, Tamil Nadu state government's new policy aims to increase the installed capacity to 3000MW by 2016.[178] Kamuthi Solar Power Project was commissioned by Adani Power in Kamuthi, Ramanathapuram district.[179] With a generating capacity of 648 MWp at a single location, it is the world's sixth largest (as of 2018) solar park.[180][181]

Culture

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Tamil Nadu is known for its rich tradition of literature, art, music and dance which continue to flourish today. Tamil Nadu is a land most known for its monumental ancient Hindu temples and classical form of dance Bharata Natyam.[183] Unique cultural features like Bharatanatyam[184] (dance), Tanjore painting,[185] and Tamil architecture were developed and continue to be practised in Tamil Nadu.[186]

Literature

Tamil written literature has existed for over 2,300 years.[187] The earliest period of Tamil literature, Sangam literature, is roughly dated from ca. 300 BCE – 300 CE.[188][189] It is one of the oldest Indian literature amongst all others.[190] The earliest epigraphic records found on rock edicts and hero stones date from around the 3rd century BCE.[191][192]

Most early Tamil literary works are in verse form, with prose not becoming more common until later periods. The Sangam literature collection contains 2381 poems composed by 473 poets, some 102 of whom remain anonymous.[193] Sangam literature is primarily secular, dealing with everyday themes in a Tamilakam context.[194] The Sangam literature also deals with human relations and emotions.[195] The available literature from this period was categorised and compiled in the 10th century into two categories based roughly on chronology. The categories are: Pathinenmaelkanakku (The Major Eighteen Anthology Series) comprising Eṭṭuttokai (The Eight Anthologies) and the Pattupattu (Ten Idylls) and Pathinenkilkanakku (The Minor Eighteen Anthology Series).

Much of Tamil grammar is extensively described in the oldest known grammar book for the Tamil language, the Tolkāppiyam.Modern Tamil is largely based on the 13th-century grammar book Naṉṉūl which restated and clarified the rules of the Tolkāppiyam, with some modifications. Traditional Tamil grammar consists of five parts, namely eḻuttu, sol, poruḷ, yāppu, aṇi. Of these, the last two are mostly applied in poetry.[196] Notable example of Tamil poetry include the Tirukkural written by Tiruvalluvar.

In 1578, the Portuguese published a Tamil book in old Tamil script named 'Thambiraan Vanakkam', thus making Tamil the first Indian language to be printed and published.[197] Tamil Lexicon, published by the University of Madras, is the first among the dictionaries published in any Indian language.[198] During the Indian Independence Movement, many Tamil poets and writers sought to provoke national spirit, social equity and secularist thoughts among the common man, notably Subramanya Bharathy and Bharathidasan.

Festivals and traditions

Pongal, also called Tamizhar Thirunaal (festival of Tamils) or Makara Sankranti elsewhere in India, a four-day harvest festival is one of the most widely celebrated festivals throughout Tamil Nadu.[199] The Tamil language saying Thai Pirandhal Vazhi Pirakkum – literally meaning, the birth of the month of Thai will pave way for new opportunities – is often quoted with reference to this festival. The first day, Bhogi Pongal is celebrated by throwing away and destroying old clothes and materials by setting them on fire to mark the end of the old and emergence of the new. The second day, Surya Pongal is the main day which falls on the first day of the tenth Tamil month of Thai (14 January or 15 January in the western calendar). On the third day, Maattu Pongal is meant to offer thanks to the cattle, as they provide milk and are used to plough the lands. Jallikattu, a bull-taming contest, marks the main event of this day. Alanganallur is famous for its Jallikattu[200][201] contest usually held on the third day of Pongal. During this final day, Kaanum Pongal – the word kaanum, means 'to view' in Tamil. In 2011 the Madras High Court Bench ordered the cockfight at Santhapadi and Modakoor Melbegam villages permitted during the Pongal festival while disposing of a petition filed attempting to ban the cockfight.[202] The first month in the Tamil calendar is Chittirai and the first day of this month in mid-April is celebrated as Tamil New Year. The Thiruvalluvar calendar is 31 years ahead of the Gregorian calendar, i.e. Gregorian 2000 is Thiruvalluvar 2031. Aadi Perukku is celebrated on the 18th day of the Tamil month Aadi, which celebrates the rising of the water level in the river Kaveri. Apart from the major festivals, in every village and town of Tamil Nadu, the inhabitants celebrate festivals for the local gods once a year and the time varies from place to place. Most of these festivals are related to the goddess Maariyamman, the mother goddess of the rain. Other major Hindu festivals including Deepavali (Death of Narakasura), Ayudha Poojai, Saraswathi Poojai (Dasara), Ayya Vaikunda Avataram, Krishna Jayanthi and Vinayaka Chathurthi are also celebrated. Eid ul-Fitr, Bakrid, Milad un Nabi, Muharram are celebrated by Muslims whereas Christmas, Good Friday, Easter are celebrated by Christians in the state. Mahamagam a bathing festival at Kumbakonam in Tamil Nadu is celebrated once in 12 years. People from all the corners of the country come to Kumbakonam for the festival. This festival is also called Kumbamela of South.[203][204]

Cuisine

Thoothukudi is the place of origin of the Thoothukudi macaroon, Tirunelveli is known for its wheat Halva, Salem is renowned for its unique mangoes, Madurai is the place of origin of the milk dessert Jigarthanda while Palani is known for its Panchamirtham.[205] Idlis, dosas, and sambar are quite common throughout the state. Coffee and tea are the staple drinks.[206]

Media

Music

In terms of modern cine-music, Ilaiyaraaja was a prominent composer of film music in Tamil cinema during the late 1970s and 1980s. His work highlighted Tamil folk lyricism and introduced broader Western musical sensibilities to the south Indian musical mainstream. Tamil Nadu is also the home of the double Oscar winner A. R. Rahman[207][208][209] who has composed film music in Tamil, Telugu, Hindi, English and Chinese films. He was once referred to by Time magazine as "The Mozart of Madras".

Film industry

Tamil Nadu is also home to the Tamil film industry nicknamed as "Kollywood", which released the most films in India in 2013.[210] The term Kollywood is a blend of Kodambakkam and Hollywood.[211] Tamil cinema is one of the largest industries of film production in India.[212] In Tamil Nadu, cinema ticket prices are regulated by the government. Single screen theatres may charge a maximum of ₹50, while theatres with more than three screens may charge a maximum of ₹120 per ticket.[213] The first silent film in Tamil Keechaka Vadham, was made in 1916.[214] The first talkie was a multi-lingual film, Kalidas, which released on 31 October 1931, barely seven months after India's first talking picture Alam Ara.[215] Swamikannu Vincent, who had built the first cinema of South India in Coimbatore, introduced the concept of "Tent Cinema" in which a tent was erected on a stretch of open land close to a town or village to screen the films. The first of its kind was established in Madras, called "Edison's Grand Cinemamegaphone". This was due to the fact that electric carbons were used for motion picture projectors.[216]

Television industry

There are more than 30 television channels of various genres in Tamil. DD Podhigai, Doordarshan's Tamil language regional channel was launched on 14 April 1993.[217] The first private Tamil channel, Sun TV Network was founded in 1993. In Tamil Nadu, the television industry is influenced by politics and majority of the channels are owned by politicians or people with political links.[218] The government of Tamil Nadu distributed free televisions to families in 2006 at an estimated cost ₹3.6 billion (US$45 million) of which has led to high penetration of TV services.[219][220] Cable used to be the preferred mode of reaching homes controlled by government run operator Arasu Cable.[221] From the early 2010s, Direct to Home has become increasingly popular replacing cable television services.[222] Tamil television serials form a major prime time source of entertainment and are directed usually by one director unlike American television series, where often several directors and writers work together.[223]

Sports

Kabbadi, also known as Sadugudu, is recognised as the state game in Tamil Nadu.[224] The traditional sports of Tamil Nadu include Silambam,[225] a Tamil martial arts played with a long bamboo staff, cockfight, Jallikattu,[226] a bull taming sport famous on festival occasions, ox-wagon racing known as Rekkala,[227][225] kite flying also known as Pattam viduthal,[226] Goli, the game with marbles,[226] Aadu Puli, the "goat and tiger" game[226] and Kabaddi also known as Sadugudu.[226] Most of these traditional sports are associated with festivals of land like Thai Pongal and mostly played in rural areas.[226] S. Ilavazhagi carrom world champion from 2002 to 2016

The M. A. Chidambaram Stadium in Chennai is an international cricket ground with a capacity of 50,000 and houses the Tamil Nadu Cricket Association.[228] Srinivasaraghavan Venkataraghavan,[229] Krishnamachari Srikkanth,[230] Laxman Sivaramakrishnan, Sadagoppan Ramesh, Hemang Badani Laxmipathy Balaji,[231] Murali Vijay,[232] Ravichandran Ashwin,[233] Dinesh Karthik, Vijay Shankar, Murali Karthik, Washington Sundar, Subramaniam Badrinath, Abhinav Mukund, and T. Natarajan are some prominent cricketers from Tamil Nadu. The MRF Pace Foundation in Chennai is a popular fast bowling academy for pace bowlers all over the world. Cricket contests between local clubs, franchises and teams are popular in the state. Chennai Super Kings represent the city of Chennai in the Indian Premier League, a popular Twenty20 league. The Super Kings are the second most successful team in the league with four IPL and two CLT20 titles.[234]

- Notable sportspersons from Tamil Nadu

.jpg.webp) Ravichandran Ashwin – Cricket

Ravichandran Ashwin – Cricket Dinesh Karthik – Cricket

Dinesh Karthik – Cricket Adam Sinclair – Field hockey

Adam Sinclair – Field hockey

P. V. Nandhidhaa – Chess Woman Grandmaster

P. V. Nandhidhaa – Chess Woman Grandmaster_(27595402684).jpg.webp) Ramkumar Ramanathan – Tennis

Ramkumar Ramanathan – Tennis Raj Bharath – Motorsport

Raj Bharath – Motorsport.jpg.webp) Mariyappan Thangavelu (left most) – High jump

Mariyappan Thangavelu (left most) – High jump_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Ajay Jayaram – Badminton

Ajay Jayaram – Badminton_Achanta_Sarath_Kamal_%2526_Subhajit_Saha_of_India_won_the_Gold_medal%252C_at_Yamuna_Sports_Complex%252C_in_Delhi_on_October_13%252C_2010.jpg.webp) Sharath Kamal (left) – Table tennis

Sharath Kamal (left) – Table tennis Joshna Chinappa and Dipika Pallikal – Squash

Joshna Chinappa and Dipika Pallikal – Squash

Tennis is also a popular sport in Tamil Nadu with notable international players including Ramesh Krishnan,[235] Ramanathan Krishnan,[235] Vijay Amritraj[236] and Mahesh Bhupathi. Nirupama Vaidyanathan, the first Indian women to play in a grand slam tournament also hails from the state. The ATP Chennai Open tournament is held in Chennai every January. The Sports Development Authority of Tamil Nadu (SDAT) owns Nungambakkam tennis stadium which hosts Chennai Open and Davis Cup play-off tournaments.

The Tamil Nadu Hockey Association is the governing body of hockey in the state. Vasudevan Baskaran was the captain of the Indian team that won the gold medal in the 1980 Olympics in Moscow. The Mayor Radhakrishnan Stadium in Chennai hosts international hockey events and is regarded by the International Hockey Federation as one of the best in the world for its infrastructure.[237]

Tamil Nadu also has golf ground in Coimbatore, The Coimbatore Golf Club is an 18-hole golf course located in Chettipalayam in Coimbatore, located within the city limits in the state of Tamil Nadu in India. The club is also a popular venue for major golf tournaments held in India.

The Sports Development Authority of Tamil Nadu (SDAT), a government body, is vested with the responsibility of developing sports and related infrastructure in the state.[238] The SDAT owns and operates world-class stadiums and organises sporting events.[239] It also accommodates sporting events, both at the domestic and international level, organised by other sports associations at its venues. The YMCA College of Physical Education at Nandanam in Chennai was established in 1920 and was the first college for physical education in Asia. The Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium in Chennai is a multi-purpose stadium hosting football and track and field events. The Indian Triathlon Federation and the Volleyball Federation of India are headquartered in Chennai. Chennai hosted India's first-ever International Beach Volleyball Championship in 2008. The SDAT – TNSRA Squash Academy in Chennai is one of the very few academics in South Asia hosting international squash events. Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium in Coimbatore is a multi-purpose stadium in Coimbatore constructed in 1971 which is used to host I-League football matches.[240]

Tourism

The tourism industry of Tamil Nadu is the largest in India, with an annual growth rate of 16 per cent. Tourism in Tamil Nadu is promoted by Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation (TTDC), a government of Tamil Nadu undertaking. According to Ministry of Tourism statistics, 4.68 million foreign (20.1% share of the country) and 333.5 million domestic tourists (23.3% share of the country) visited the state in 2015 making it the most visited state in India both domestic and foreign tourists.[241] The state boasts some of the grand Hindu temples built-in Dravidian architecture. The Nilgiri Mountain Railway, Brihadishwara Temple in Thanjavur, Gangaikonda Cholapuram and the Airavatesvara Temple in Darasuram (Great Chola Temples) and the Shore Temple along with the collection of other monuments in Mamallapuram which have been declared as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[242][243]

See also

- Chronology of Tamil history

- History of Tamil Nadu

- List of countries where Tamil is an official language

- List of denotified communities of Tamil Nadu

- List of dams and reservoirs in Tamil Nadu

- Outline of Tamil Nadu

- Tamil Eelam

- Tamil inscriptions

- Tamil Muslim

- Tamizhi

Notes

- 1.^ The total sum of area of all districts from the data provided on the official Tamil Nadu Government website, https://www.tn.gov.in/district_view is 132,862 Sq.Km

References

Citations

- "Tamil Nadu: K. Shanmugam appointed as new Tamil Nadu Chief Secretary". The Hindu. Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- "Census of india 2011" (PDF). Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- . 15 April 2021 http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/press_releases_statements/State_wise_SDP_15_03_2021.xls. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "52nd report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2014 to June 2015)" (PDF). Ministry of Minority Affairs (Government of India). 29 March 2016. p. 132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly history 2012.

- UNESCO 2012.

- Press Information Bureau releases 2012.

- "The Living culture of the Tamils; The UNESCO Courier: a window open on the world" (PDF). The UNESCO Courier. XXXVII (3). March 1984. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- • Swaminathan, Padmini (28 May 1994), "Where Are the Entrepreneurs? What the Data Reveal for Tamil Nadu", Economic and Political Weekly, 29 (22): 64–74, ISSN 0012-9976, JSTOR 4401265

• Alagarsamy, R.; Srinivasan, Dr.R. (February 2013). "AN EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION INTO LOCAL PUBLIC OPINION ON SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONES IN SELECTED DISTRICTS IN TAMIL NADU" (PDF). Shanlax International. 1 (2): 62. ISSN 2319-961X. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

• Aiyappan, Ayinipalli, "Tamil Nadu", Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved 6 July 2020,Tamil Nadu is one of the most industrialised of the Indian states, and the manufacturing sector accounts for more than one-third of the state's gross product.

- Nobrega & Sinha 2008, p. 20.

- "Science News : Archaeology – Anthropology : Sharp stones found in India signal surprisingly early toolmaking advances". 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- "The Washington Post : Very old, very sophisticated tools found in India. The question is: Who made them?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- "Significance of Mayiladuthurai find". The Hindu. 1 May 2006. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- T, Saravanan (22 February 2018). "How a recent archaeological discovery throws light on the history of Tamil script".

- "the eternal harappan script". Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "Skeletons dating back 3,800 years throw light on evolution". The Times of India. 1 January 2006. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- "The Hindu: National: 'Rudimentary Tamil-Brahmi script' unearthed at Adichanallur". The Hindu. 17 December 2005. Archived from the original on 28 January 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "National: Skeletons, script found at ancient burial site in Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 26 May 2004. Archived from the original on 1 July 2004. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- Staff Reporter (22 November 2005). "Students get glimpse of heritage". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 18 May 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- Skeletons dating back 3,800 years throw light on evolution Archived 14 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. The Times of India.

- "The Hindu : National : 'Rudimentary Tamil-Brahmi script' unearthed at Adichanallur". Archived from the original on 28 January 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Caldwell 1974, p. 88.

- Ayyar 1991, pp. 498–499.

- K.A.N. Sashtri, A History of South India, pp 109–112

- K.A.N. Sastri, A History of South India, OUP (1955) p 124

- Kamil Veith Zvelebil, Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, p 12

- "Keezhadi sixth phase: What do the findings so far tell us?". The News Minute. 21 August 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2021.