Turkish people

The Turkish people, or simply Turks (Turkish: Türkler), are the world's largest Turkic ethnic group; they speak various dialects of the Turkish language and form a majority in Turkey and Northern Cyprus. In addition, centuries-old ethnic Turkish communities still live across other former territories of the Ottoman Empire. The ethnic Turks can therefore be distinguished by a number of cultural and regional variants, but do not function as separate ethnic groups.[97][81] In particular, the culture of the Anatolian Turks in Asia Minor underlies the Turkish nationalist ideology.[97] Other Turkish groups include the Rumelian Turks historically in the Balkans, today mostly living in Turkey;[81][98] Turkish Cypriots on the island of Cyprus, Meskhetian Turks originally based in Meskheti, Georgia;[99] and ethnic Turkish people across the Middle East,[81] where they are also called "Turkmen" or "Turkoman" in the Levant (e.g., Iraqi Turkmen, Syrian Turkmen, Lebanese Turkmen, etc.).[100] Consequently, the Turks form the largest minority group in Bulgaria,[61] the second largest minority group in Iraq,[46] Libya,[101] North Macedonia,[64] and Syria,[94] and the third largest minority group in Kosovo.[73] They also form substantial communities in the Western Thrace region of Greece, the Dobruja region of Romania, the Akkar region in Lebanon, as well as minority groups in other post-Ottoman Balkan and Middle Eastern countries. Mass immigration due to fleeing ethnic cleansing after the persecution of Muslims during Ottoman contraction has led to mass migrations from the 19th century onward; these Turkish communities have all contributed to the formation of a Turkish diaspora outside the former Ottoman lands. Approximately 2 million Turks were massacred between 1870–1923 and those who escaped it settled in Turkey as muhacirs.[102][103][104][105] The mass immigration of Turks also led to them forming the largest ethnic minority group in Austria,[106] Denmark,[107] Germany,[108] and the Netherlands.[108] There are also Turkish communities in other parts of Europe as well as in North America, Australia and the Post-Soviet states. Turks are the 13th largest ethnic group in the world.

Türkler | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 80 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Modern Turkish diaspora: | |

| 3,000,000 to over 7,000,000[4][5][6][7] | |

| 500,000 to over 2,000,000[8][9][10][11] | |

| over 1,000,000[12][13][14] | |

| over 1,000,000[15][16] | |

| 500,000b[17][18] | |

| 360,000–500,000[19][20] | |

| 250,000–500,000[21][22] | |

| 320,000c[23][24] | |

| 250,000d[25] | |

| 185,000e[26][27][28] | |

| 109,883–150,000[29][30] | |

| 130,000d[25] | |

| 120,000[31] | |

| over 100,000[32] | |

| 70,000–75,000[33][34] | |

| 55,000d[25] | |

| 50,000[35] | |

| 25,000d[25] | |

| 16,500[36] | |

| 8,844–15,000[37][25] | |

| 13,000[38] | |

| 10,000[39] | |

| 5,000[40] | |

| 3,600–4,600f[41][24] | |

| 2,000–3,000[42] | |

| 2,000-6,300[43][44] | |

| 1,000[45] | |

| Turkish minorities in the Middle East: | |

| 3,000,000–5,000,000[46][47][48] | |

| 1,000,000–1,700,000g[49][50] | |

| 1,000,000–1,400,000h[51][52] | |

| 100,000–1,500,000[53] | |

| 280,000i[54][55] | |

| 270,000–350,000[56][57] | |

| 10,000-100,000[58] | |

| 50,000[59] | |

| Turkish minorities in the Balkans: | |

| 588,318–800,000[60][61][62] | |

| 77,959–200,000[63][64] | |

| 49,000–130,000[65][66][67][68] | |

| 28,226–80,000[69][70][71] | |

| 18,738–60,000[72][73][74] | |

| 1,108[75] | |

| 714[76] | |

| 647[77] | |

| 367[78] | |

| 104[79] | |

| Languages | |

| Turkish | |

| Religion | |

| Mainly Islam (practising and non-practising), mostly Sunni, followed by Alevi or non-denominational. Minority Christianity and Judaism. Many also irreligious. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Azerbaijanis,[80] Turkmens[80] Gagauz people[80] | |

a Approximately 200,000 are Turkish Cypriots and the remainder are Turkish settlers.[81] b Turkish Cypriots form 300,000[82] to 400,000[83] of the Turkish-British population. Mainland Turks are the next largest group, followed by Turkish Bulgarians and Turkish Romanians.[84] Turkish minorities have also settled from Iraq,[85] Greece,[86] etc. c Turkish Australians include 200,000 mainland Turks,[23] 120,000 Turkish Cypriots,[24] and smaller Turkish groups from Bulgaria,[87] Greece,[88] North Macedonia,[88] Syria,[89] and Western Europe.[88] d These figures only include Turkish Meskhetians. Official censuses are considered unreliable because many Turks have incorrectly been registered as "Azeri",[90][91] "Kazakh",[92] "Kyrgyz",[93] and "Uzbek".[93] e The Turkish Swedish community includes 150,000 mainland Turks,[26] 30,000 Turkish Bulgarians,[27] 5,000 Turkish Macedonians,[28] and smaller groups from Iraq and Syria. f Including 2,000–3,000 mainland Turks[41] and 1,600 Turkish Cypriots.[24] g This includes the Turkish-speaking minority only (i.e. 30% of Syrian Turks).[94] Estimates including the Arabized Turks range between 3.5 to 6 million.[95] h Includes the Kouloughlis who are descendants of the old Turkish ruling class.[96] i Includes 80,000 Turkish Lebanese[54] and 200,000 recent refugees from Syria.[55] | |

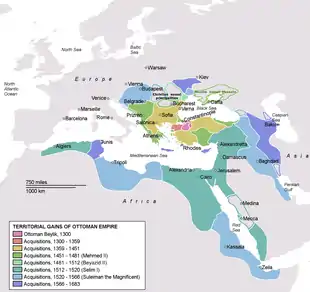

Turks from Central Asia settled in Anatolia in the 11th century, through the conquests of the Seljuk Turks. This began the transformation of the region, which had been a largely Greek-speaking region after previously being Hellenized, into a Turkish Muslim one.[109][110][111] The Ottoman Empire came to rule much of the Balkans, the South Caucasus, the Middle East (excluding Iran, even though they controlled parts of it), and North Africa over the course of several centuries. The empire lasted until the end of the First World War, when it was defeated by the Allies and partitioned. Following the Turkish War of Independence that ended with the Turkish National Movement retaking much of the territory lost to the Allies, the Movement ended the Ottoman Empire on 1 November 1922 and proclaimed the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923.

Article 66 of the Turkish Constitution defines a "Turk" as: "Anyone who is bound to the Turkish state through the bond of citizenship." While the legal use of the term "Turkish" as it pertains to a citizen of Turkey is different from the term's ethnic definition,[112][113] the majority of the Turkish population (an estimated 70 to 75 percent) are of Turkish ethnicity.[114][115] The vast majority of Turks are Muslims and follow the Sunni and Alevi faith.[81]

Etymology and definition

Etymology

The first definite references to the "Turks" mainly come from Chinese sources which date back to the sixth century. In these sources, "Turk" appears as "Tujue" (Chinese: 突厥; Wade–Giles: T’u-chüe), which referred to the Göktürks.[116][117]

There are several theories regarding the origin of the ethnonym "Turk". There is a claim that it may be connected to Herodotus's (c. 484–425 BC) reference to Targitaos, a king of the Scythians;[118] however, Mayrhofer (apud Lincoln) assigned Iranian etymology for Ταργιτάος Targitaos from Old Iranian *darga-tavah-, meaning "he whose strength is long-lasting".[119] During the first century AD., Pomponius Mela refers to the "Turcae" in the forests north of the Sea of Azov, and Pliny the Elder lists the "Tyrcae" among the people of the same area.;[118] yet English archaeologist Ellis Minns contended that Tyrcae Τῦρκαι is "a false correction" for Ἱύρκαι Iyrcae/Iyrkai, a people who dwelt beyond the Thyssagetae, according to Herodotus (Histories, iv. 22)[120] There are references to certain groups in antiquity whose names might have been foreign transcriptions of Tür(ü)k such as Togarma, Turukha/Turuška, Turukku and so on; but according to American historian Peter B. Golden, while any connection of some of these ancient peoples to Turks is possible, it is rather unlikely.[121]

Definition

In the 19th century, the word Türk referred to Anatolian peasants. The Ottoman ruling class identified themselves as Ottomans, not as Turks.[122][123] In the late 19th century, as the Ottoman upper classes adopted European ideas of nationalism, the term Türk took on a more positive connotation.[124]

During Ottoman times, the millet system defined communities on a religious basis, and today some regard only those who profess the Sunni faith as true Turks. Turkish Jews, Christians, and Alevis are not considered Turks by some.[123] In the early 20th century, the Young Turks abandoned Ottoman nationalism in favor of Turkish nationalism, while adopting the name Turks, which was finally used in the name of the new Turkish Republic.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk defined the Turkish nation as the "people (halk) who established the Turkish republic". Further, "the natural and historical facts which effected the establishment (teessüs) of the Turkish nation" were "(a) unity in political existence, (b) unity in language, (c) unity in homeland, (d) unity in race and origin (menşe), (e) to be historically related and (f) to be morally related".[125]

Article 66 of the Turkish Constitution defines a "Turk" as anyone who is "bound to the Turkish state through the bond of citizenship."[126]

History

Prehistory, Ancient era, and Early Middle Ages

Anatolia was first inhabited by hunter-gatherers during the Paleolithic era, and in antiquity was inhabited by various ancient Anatolian peoples.[127][a] After Alexander the Great's conquest in 334 BC, the area was Hellenized, and by the first century BC it is generally thought that the native Anatolian languages, themselves earlier newcomers to the area, following the Indo-European migrations, became extinct.[128][129]

The early Turkic peoples descended from agricultural communities in Northeast Asia who moved westwards into the Mongolian Plateau in the late 3rd millennium BC, where they adopted a pastoral lifestyle.[130][131][132][133][134] By the early 1st millennium BC, these peoples had become equestrian nomads.[130] In subsequent centuries, the steppe populations of Central Asia appear to have been progressively replaced and Turkified by East Asian nomadic Turks, moving out of the Mongolian Plateau.[135][136] In Central Asia, the earliest surviving Turkic language texts, found on the eighth-century Orkhon inscription monuments, were erected by the Göktürks in the sixth century CE, and include words not common to Turkic but found in unrelated Inner Asian languages.[137] Although the ancient Turks were nomadic, they traded wool, leather, carpets, and horses for wood, silk, vegetables and grain, as well as having large ironworking stations in the south of the Altai Mountains during the 600s CE. Most of the Turkic peoples were followers of Tengrism, sharing the cult of the sky god Tengri, although there were also adherents of Manichaeism, Nestorian Christianity, and Buddhism.[138][118] However, during the Muslim conquests, the Turks entered the Muslim world proper as slaves, the booty of Arab raids and conquests.[118] The Turks began converting to Islam after the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana through the efforts of missionaries, Sufis, and merchants. Although initiated by the Arabs, the conversion of the Turks to Islam was filtered through Persian and Central Asian culture. Under the Umayyads, most were domestic servants, whilst under the Abbasid Caliphate, increasing numbers were trained as soldiers.[118] By the ninth century, Turkish commanders were leading the caliphs’ Turkish troops into battle. As the Abbasid Caliphate declined, Turkish officers assumed more military and political power by taking over or establishing provincial dynasties with their own corps of Turkish troops.[118]

Seljuk era

During the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks, who were influenced by Persian civilization in many ways, grew in strength and succeeded in taking the eastern province of the Abbasid Empire. By 1055, the Seljuks captured Baghdad and began to make their first incursions into Anatolia.[139] When they won the Battle of Manzikert against the Byzantine Empire in 1071, it opened the gates of Anatolia to them.[140] Although ethnically Turkish, the Seljuk Turks appreciated and became carriers of Persian culture rather than Turkish culture.[141][142] Nonetheless, the Turkish language and Islam were introduced and gradually spread over the region and the slow transition from a predominantly Christian and Greek-speaking Anatolia to a predominantly Muslim and Turkish-speaking one was underway.[140]

In dire straits, the Byzantine Empire turned to the West for help, setting in motion the pleas that led to the First Crusade.[143] Once the Crusaders took Iznik, the Seljuk Turks established the Sultanate of Rum from their new capital, Konya, in 1097.[140] By the 12th century, Europeans had begun to call the Anatolian region "Turchia" or "Turkey", the land of the Turks.[144] The Turkish society in Anatolia was divided into urban, rural and nomadic populations;[145] other Turkoman (Turkmen) tribes who had arrived into Anatolia at the same time as the Seljuks kept their nomadic ways.[140] These tribes were more numerous than the Seljuks, and rejecting the sedentary lifestyle, adhered to an Islam impregnated with animism and shamanism from their Central Asian steppeland origins, which then mixed with new Christian influences. From this popular and syncretist Islam, with its mystical and revolutionary aspects, sects such as the Alevis and Bektashis emerged.[140] Furthermore, intermarriage between the Turks and local inhabitants, as well as the conversion of many to Islam, also increased the Turkish-speaking Muslim population in Anatolia.[140][146]

By 1243, at the Battle of Köse Dağ, the Mongols defeated the Seljuk Turks and became the new rulers of Anatolia, and in 1256, the second Mongol invasion of Anatolia caused widespread destruction. Particularly after 1277, political stability within the Seljuk territories rapidly disintegrated, leading to the strengthening of Turkoman principalities in the western and southern parts of Anatolia called the "beyliks".[147]

Beyliks era

When the Mongols defeated the Seljuk Turks and conquered Anatolia, the Turks became the vassals of the Ilkhans who established their own empire in the vast area which stretched from present-day Afghanistan to present-day Turkey.[148] As the Mongols occupied more lands in Asia Minor, the Turks moved further into western Anatolia and settled in the Seljuk-Byzantine frontier.[148] By the last decades of the 13th century, the Ilkhans and their Seljuk vassals lost control over much of Anatolia to these Turkoman peoples.[148] A number of Turkish lords managed to establish themselves as rulers of various principalities, known as "Beyliks" or emirates. Amongst these beyliks, along the Aegean coast, from north to south, stretched the beyliks of Karasi, Saruhan, Aydin, Menteşe, and Teke. Inland from Teke was Hamid and east of Karasi was the beylik of Germiyan.

To the northwest of Anatolia, around Söğüt, was the small and, at this stage, insignificant, Ottoman beylik. It was hemmed into the east by other more substantial powers like Karaman on Iconium, which ruled from the Kızılırmak River to the Mediterranean. Although the Ottomans was only a small principality among the numerous Turkish beyliks, and thus posed the smallest threat to the Byzantine authority, their location in north-western Anatolia, in the former Byzantine province of Bithynia, became a fortunate position for their future conquests. The Latins, who had conquered the city of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, established a Latin Empire (1204–1261), divided the former Byzantine territories in the Balkans and the Aegean among themselves, and forced the Byzantine Emperors into exile at Nicaea (present-day Iznik). From 1261 onwards, the Byzantines were largely preoccupied with regaining their control in the Balkans.[148] Toward the end of the 13th century, as Mongol power began to decline, the Turkoman chiefs assumed greater independence.[149]

Ottoman Empire

Under its founder, Osman I, the nomadic Ottoman beylik expanded along the Sakarya River and westward towards the Sea of Marmara. Thus, the population of western Asia Minor had largely become Turkish-speaking and Muslim in religion.[148] It was under his son, Orhan I, who had attacked and conquered the important urban center of Bursa in 1326, proclaiming it as the Ottoman capital, that the Ottoman Empire developed considerably. In 1354, the Ottomans crossed into Europe and established a foothold on the Gallipoli Peninsula while at the same time pushing east and taking Ankara.[150][151] Many Turks from Anatolia began to settle in the region which had been abandoned by the inhabitants who had fled Thrace before the Ottoman invasion.[152] However, the Byzantines were not the only ones to suffer from the Ottoman advance for, in the mid-1330s, Orhan annexed the Turkish beylik of Karasi. This advancement was maintained by Murad I who more than tripled the territories under his direct rule, reaching some 100,000 square miles (260,000 km2), evenly distributed in Europe and Asia Minor.[153] Gains in Anatolia were matched by those in Europe; once the Ottoman forces took Edirne (Adrianople), which became the capital of the Ottoman Empire in 1365, they opened their way into Bulgaria and Macedonia in 1371 at the Battle of Maritsa.[154] With the conquests of Thrace, Macedonia, and Bulgaria, significant numbers of Turkish emigrants settled in these regions.[152] This form of Ottoman-Turkish colonization became a very effective method to consolidate their position and power in the Balkans. The settlers consisted of soldiers, nomads, farmers, artisans and merchants, dervishes, preachers and other religious functionaries, and administrative personnel.[155]

In 1453, Ottoman armies, under Sultan Mehmed II, conquered Constantinople.[153] Mehmed reconstructed and repopulated the city, and made it the new Ottoman capital.[156] After the Fall of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire entered a long period of conquest and expansion with its borders eventually going deep into Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.[157] Selim I dramatically expanded the empire's eastern and southern frontiers in the Battle of Chaldiran and gained recognition as the guardian of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.[158] His successor, Suleiman the Magnificent, further expanded the conquests after capturing Belgrade in 1521 and using its territorial base to conquer Hungary, and other Central European territories, after his victory in the Battle of Mohács as well as also pushing the frontiers of the empire to the east.[159] Following Suleiman's death, Ottoman victories continued, albeit less frequently than before. The island of Cyprus was conquered, in 1571, bolstering Ottoman dominance over the sea routes of the eastern Mediterranean.[160] However, after its defeat at the Battle of Vienna, in 1683, the Ottoman army was met by ambushes and further defeats; the 1699 Treaty of Karlowitz, which granted Austria the provinces of Hungary and Transylvania, marked the first time in history that the Ottoman Empire actually relinquished territory.[161]

By the 19th century, the empire began to decline when ethno-nationalist uprisings occurred across the empire. Thus, the last quarter of the 19th and the early part of the 20th century saw some 7–9 million Muslim refugees (Turks and some Circassians, Bosnians, Georgians, etc.) from the lost territories of the Caucasus, Crimea, Balkans, and the Mediterranean islands migrate to Anatolia and Eastern Thrace.[162] By 1913, the government of the Committee of Union and Progress started a program of forcible Turkification of non-Turkish minorities.[163][164] By 1914, the World War I broke out, and the Turks scored some success in Gallipoli during the Battle of the Dardanelles in 1915. During World War I, the government of the Committee of Union and Progress continued to implement its Turkification policies, which affected non-Turkish minorities, such as the Armenians during the Armenian genocide and the Greeks during various campaigns of ethnic cleansing and expulsion.[165][166][167][168][169] In 1918, the Ottoman Government agreed to the Mudros Armistice with the Allies.

In addition to non-Turkish minorities experiencing ethnic cleansing under the Young Turks, Turkish populations in Balkans, Caucasus and Anatolia were ethnically cleansed in what is known as the Persecution of Muslims during Ottoman contraction, where an estimated 2 million Turkish people were killed or deported.[170][171][172] Paul Mojzes has called the Balkan Wars an ''unrecognized genocide''.[173]

The Treaty of Sèvres —signed in 1920 by the government of Mehmet VI— dismantled the Ottoman Empire. The Turks, under Mustafa Kemal Pasha, rejected the treaty and fought the Turkish War of Independence, resulting in the abortion of that text, never ratified,[174] and the abolition of the Sultanate. Thus, the 623-year-old Ottoman Empire ended.[175]

Modern era

.jpg.webp)

Once Mustafa Kemal led the Turkish War of Independence against the Allied forces that occupied the former Ottoman Empire, he united the Turkish Muslim majority and successfully led them from 1919 to 1922 in overthrowing the occupying forces out of what the Turkish National Movement considered the Turkish homeland.[176] The Turkish identity became the unifying force when, in 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed and the newly founded Republic of Turkey was formally established. Atatürk's presidency was marked by a series of radical political and social reforms that transformed Turkey into a secular, modern republic with civil and political equality for sectarian minorities and women.[177]

Throughout the 1920s and the 1930s, Turks, as well as other Muslims, from the Balkans, the Black Sea, the Aegean islands, the island of Cyprus, the Sanjak of Alexandretta (Hatay), the Middle East, and the Soviet Union continued to arrive in Turkey, most of whom settled in urban north-western Anatolia.[178][179] The bulk of these immigrants, known as "Muhacirs", were the Balkan Turks who faced harassment and discrimination in their homelands.[178] However, there were still remnants of a Turkish population in many of these countries because the Turkish government wanted to preserve these communities so that the Turkish character of these neighbouring territories could be maintained.[180] One of the last stages of ethnic Turks immigrating to Turkey was between 1940 and 1990 when about 700,000 Turks arrived from Bulgaria. Today, between a third and a quarter of Turkey's population are the descendants of these immigrants.[179]

Geographic distribution

Turkey

.jpg.webp)

The ethnic Turks are the largest ethnic group in Turkey and number approximately 60 million[1] to 65 million.[2] Due to differing historical Turkish migrations to the region, dating from the Seljuk conquests in the 11th century to the continuous Turkish migrations which have persisted to the present day (especially Turkish refugees from neighboring countries), there are various accents and customs which can distinguish the ethnic Turks by geographic sub-groups.[97] For example, the most significant are the Anatolian Turks in the central core of Asiatic Turkey whose culture was influential in underlining the roots of the Turkish nationalist ideology.[97] There are also nomadic Turkic tribes who descend directly from Central Asia, such as the Yörüks;[97] the Black Sea Turks in the north whose "speech largely lacks the vowel harmony valued elsewhere";[97] the descendants of muhacirs (Turkish refugees) who fled persecution from former Ottoman territories in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries;[97] and more recent refugees who have continued to flee discrimination and persecution since the mid-1900s.

Initially, muhacirs who arrived in Eastern Thrace and Anatolia came fleeing from former Ottoman territories which had been annexed by European colonial powers (such as France in Algeria or Russia in Crimea); however, the largest waves of ethnic Turkish migration came from the Balkans during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the Balkan Wars led to most of the region becoming independent from Ottoman control.[181] The largest waves of muhacirs came from the Balkans (especially Bulgaria, Greece, Romania and Yugoslavia); however, substantial numbers also came from Cyprus,[182] the Sanjak of Alexandretta,[182] the Middle East (including Trans-Jordan[182] and Yemen[182]) North African (such as Algeria[183] and Libya[184]) and the Soviet Union (especially from Meskheti).[182]

The Turks who remained in the former Ottoman territories continued to face discrimination and persecution thereafter leading many to seek refuge in Turkey, especially Turkish Meskhetians deported by Joseph Stalin in 1944; Turkish minorities in Yugoslavia (i.e., Turkish Bosnians, Turkish Croatians, Turkish Kosovars, Turkish Macedonians, Turkish Montenegrins and Turkish Serbians) fleeing Josip Broz Tito's regime in the 1950s;[185] Turkish Cypriots fleeing the Cypriot intercommunal violence of 1955–74;[186] Turkish Iraqis fleeing discrimination during the rise of Arab nationalism in the 1950s and 1970s followed by the Iran–Iraq War of 1980–88;[187] Turkish Bulgarians fleeing the Bulgarisation policies of the so-called "Revival Process" under the communist ruler Todor Zivkov in the 1980s;[87] and Turkish Kosovars fleeing the Kosovo War of 1998–99.[188]

Today, approximately 15–20 million Turks living in Turkey are the descendants of refugees from the Balkans;[189] there are also 1.5 million descendants from Meskheti[190] and over 600,000 descendants from Cyprus.[191] The Republic of Turkey continues to be a land of migration for ethnic Turkish people fleeing persecution and wars. For example, there are approximately 1 million Syrian Turkmen living in Turkey due to the current Syrian civil war.[192]

Cyprus

The Turkish Cypriots are the ethnic Turks whose Ottoman Turkish forebears colonized the island of Cyprus in 1571. About 30,000 Turkish soldiers were given land once they settled in Cyprus, which bequeathed a significant Turkish community. In 1960, a census by the new Republic's government revealed that the Turkish Cypriots formed 18.2% of the island's population.[193] However, once inter-communal fighting and ethnic tensions between 1963 and 1974 occurred between the Turkish and Greek Cypriots, known as the "Cyprus conflict", the Greek Cypriot government conducted a census in 1973, albeit without the Turkish Cypriot populace. A year later, in 1974, the Cypriot government's Department of Statistics and Research estimated the Turkish Cypriot population was 118,000 (or 18.4%).[194] A coup d'état in Cyprus on 15 July 1974 by Greeks and Greek Cypriots favoring union with Greece (also known as "Enosis") was followed by military intervention by Turkey whose troops established Turkish Cypriot control over the northern part of the island.[195] Hence, census's conducted by the Republic of Cyprus have excluded the Turkish Cypriot population that had settled in the unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.[194] Between 1975 and 1981, Turkey encouraged its own citizens to settle in Northern Cyprus; a report by CIA suggests that 200,000 of the residents of Cyprus are Turkish.

Balkans

Ethnic Turks continue to inhabit certain regions of Greece, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Romania, and Bulgaria since they first settled there during the Ottoman period. As of 2019, the Turkish population in the Balkans is over 1 million.[196] Majority of Balkan Turks were killed or deported in the Muslim Persecution during Ottoman Contraction and arrived to Turkey as Muhacirs.[197][198]

The majority of the Rumelian/Balkan Turks are the descendants of Ottoman settlers. However, the first significant wave of Anatolian Turkish settlement to the Balkans dates back to the mass migration of sedentary and nomadic subjects of the Seljuk sultan Kaykaus II (b. 1237 – d. 1279/80) who had fled to the court of Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1262.[199]

Albania

The Turkish Albanians are one of the smallest Turkish communities in the Balkans. Once Albania came under Ottoman rule, Turkish colonization was scarce there; however, some Anatolian Turkish settlers did arrive in 1415–30 and were given timar estates.[200] According to the 2011 census, the Turkish language was the sixth most spoken language in the country (after Albanian, Greek, Macedonian, Romani, and Aromanian).[76]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Turkish Bosnians have lived in the region since the Ottoman rule of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Thus, the Turks form the oldest ethnic minority in the country.[201] The Turkish Bosnian community decreased dramatically due to mass emigration to Turkey when Bosnia and Herzegovina came under Austro-Hungarian rule.[201]

In 2003 the Parliamentary Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted the "Law on the Protection of Rights of Members of National Minorities" which officially protected the Turkish minority's cultural, religious, educational, social, economic, and political freedoms.[202]

Bulgaria

.png.webp)

The Turks of Bulgaria form the largest Turkish community in the Balkans as well as the largest ethnic minority group in Bulgaria. According to the 2011 census, they form a majority in the Kardzhali Province (66.2%) and the Razgrad Province (50.02%), as well as substantial communities in the Silistra Province (36.09%), the Targovishte Province (35.80%), and the Shumen Province (30.29%). They were ethnically cleansed during the Muslim Persecution during Ottoman Contraction and subsequently targeted during the Revival Process that aimed to assimilate them into a Bulgarian identity.[197][203]

Croatia

The Turkish Croatians began to settle in the region during the various Croatian–Ottoman wars. Despite being a small minority, the Turks are among the 22 officially recognized national minorities in Croatia.[204]

Kosovo

The Turkish Kosovars are the third largest ethnic minority in Kosovo (after the Serbs and Bosniaks). They form a majority in the town and municipality of Mamuša.

Montenegro

The Turkish Montenegrins form the smallest Turkish minority group in the Balkans. They began to settle in the region following the Ottoman rule of Montenegro. A historical event took place in 1707 which involved the killing of the Turks in Montenegro as well as the murder of all Muslims. This early example of ethnic cleaning features in the epic poem The Mountain Wreath (1846).[205] After the Ottoman withdrawal, the majority of the remaining Turks emigrated to Istanbul and Izmir.[206] Today, the remaining Turkish Montenegrins predominately live in the coastal town of Bar.

North Macedonia

The Turkish Macedonians form the second largest Turkish community in the Balkans as well as the second largest minority ethnic group in North Macedonia. They form a majority in the Centar Župa Municipality and the Plasnica Municipality as well as substantial communities in the Mavrovo and Rostuša Municipality, the Studeničani Municipality, the Dolneni Municipality, the Karbinci Municipality, and the Vasilevo Municipality.

Romania

The Turkish Romanians are centered in the Northern Dobruja region. The only settlement which still has a Turkish majority population is in Dobromir located in the Constanța County. Historically, Turkish Romanians also formed a majority in other regions, such as the island of Ada Kaleh which was destroyed and flooded by the Romanian government for the construction of the Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station.

Serbia

The Turkish Serbians have lived in Serbia since the Ottoman conquests in the region. They have traditionally lived in the urban areas of Serbia. In 1830, when the Principality of Serbia was granted autonomy, most Turks emigrated as "muhacirs" (refugees) to Ottoman Turkey, and by 1862 almost all of the remaining Turks left Central Serbia, including 3,000 from Belgrade.[207] Today, the remaining community mostly live in Belgrade and Sandžak.

Azerbaijan

The Turkish Azerbaijanis began to settle in the region during the Ottoman rule, which lasted between 1578 and 1603. By 1615, the Safavid ruler, Shah Abbas I, solidified control of the region and then deported thousands of people from Azerbaijan.[208] In 1998, there was still approximately 19,000 Turks living in Azerbaijan who descended from the original Ottoman settlers; they are distinguishable from the rest of Azeri society because they practice Sunni Islam (rather than the dominant Shia sect in the country).[209]

Since the Second World War, the Turkish Azerbaijani community has increased significantly due to the mass wave of Turkish Meskhetian refugees who arrived during the Soviet rule.

Abkhazia

The Turkish Abkhazians began to live in Abkhazia during the sixteenth century under Ottoman rule.[210] Today, there are still Turks who continue to live in the region.[211]

Meskheti

Prior to the Ottoman conquest of Meskheti in Georgia, hundreds of thousands of Turkic invaders had settled in the region from the thirteenth century.[212] At this time, the main town, Akhaltsikhe, was mentioned in sources by the Turkish name "Ak-sika", or "White Fortress". Thus, this accounts for the present day Turkish designation of the region as "Ahıska".[212] Local leaders were given the Turkish title "Atabek" from which came the fifteenth century name of one of the four kingdoms of what had been Georgia, Samtskhe-Saatabago, "the land of the Atabek called Samtskhe [Meskhetia]".[212] In 1555 the Ottomans gained the western part of Meskheti after the Peace of Amasya treaty, whilst the Safavids took the eastern part.[213] Then in 1578 the Ottomans attacked the Safavid controlled area which initiated the Ottoman–Safavid War (1578–1590). Meskheti was fully secured into the Ottoman Empire in 1639 after a treaty signed with Iran brought an end to Iranian attempts to take the region. With the arrival of more Turkish colonizers, the Turkish Meskhetian community increased significantly.[214]

However, once the Ottomans lost control of the region in 1883, many Turkish Meskhetians migrated from Georgia to Turkey. Migrations to Turkey continued after the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) followed by the Bolshevik Revolution (1917), and then after Georgia was incorporated into the Soviet Union.[214] During this period, some members of the community also relocated to other Soviet borders, and those who remained in Georgia were targeted by the Sovietisation campaigns.[214] Thereafter, during World War II, the Soviet administration initiated a mass deportation of the remaining 115,000 Turkish Meskhetians in 1944,[215] forcing them to resettle in the Caucasus and the Central Asian Soviet republics.[214]

Thus, today hundreds of thousands of Turkish Meskhetians are scattered throughout the Post Soviet states (especially in Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Ukraine). Moreover, many have settled in Turkey and the United States. Attempts to repatriate them back to Georgia saw Georgian authorities receive applications covering 9,350 individuals within the a two-year application period (up until 1 January 2010).[216]

Iraq

Commonly referred to as the Iraqi Turkmens, the Turks are the second largest ethnic minority group in Iraq (i.e. after the Kurds). The majority are the descendants of Ottoman settlers (e.g. soldiers, traders and civil servants) who were brought into Iraq from Anatolia.[217] Today, most Iraqi Turkmen live in a region they refer to as "Turkmeneli" which stretches from the northwest to the east at the middle of Iraq with Kirkuk placed as their cultural capital.

Historically, Turkic migrations to Iraq date back to the 7th century when Turks were recruited in the Umayyad armies of Ubayd-Allah ibn Ziyad followed by thousands more Turkmen warriors arriving under the Abbasid rule. However, most of these Turks became assimilated into the local Arab population.[217] The next large scale migration occurred under the Great Seljuq Empire after Sultan Tuğrul Bey's invasion in 1055.[217] For the next 150 years, the Seljuk Turks placed large Turkmen communities along the most valuable routes of northern Iraq.[218] Yet, the largest wave of Turkish migrations occurred under the four centuries of Ottoman rule (1535–1919).[217][219] In 1534, Suleiman the Magnificent secured Mosul within the Ottoman Empire and it became the chief province (eyalet) responsible for administrative districts in the region. The Ottomans encouraged migration from Anatolia and the settlement of Turks along northern Iraq.[220] After 89 years of peace, the Ottoman–Safavid War (1623–1639) saw Murad IV recapturing Baghdad and taking permanent control over Iraq which resulted in the influx of continuous Turkish settlers until Ottoman rule came to an end in 1919.[219][218][221]

After the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, the Iraqi Turkmens initially sought for Turkey to annex the Mosul Vilayet.[219] However, they participated in elections for the Constituent Assembly with the condition of preserving the Turkish character in Kirkuk's administration and the recognition of Turkish as the liwa's official language.[222] Although they were recognized as a constitutive entity of Iraq, alongside the Arabs and Kurds, in the constitution of 1925, the Iraqi Turkmen were later denied this status.[219] Thereafter, the Iraqi Turkmen found themselves increasingly discriminated against from the policies of successive regimes, such as the Kirkuk Massacre of 1923, 1947, 1959 and in 1979 when the Ba'th Party discriminated against the community.[219]

Thus, the position of the Iraqi Turkmens has changed from historically being administrative and business classes of the Ottoman Empire to an increasingly discriminated minority.[219] Arabization and Kurdification policies have seen Iraqi Turkmens pushed out of their homeland and thus various degrees of suppression and assimilation have ranged from political persecution and exile to terror and ethnic cleansing.[223] Many Iraqi Turkmen have consequently sought refuge in Turkey whilst there has also been increasing migration to Western Europe (especially Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom) as well as Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

Egypt

The Turkish Egyptians are mostly the descendants of Turkish settlers who arrived during the Ottoman rule of Egypt (1517–1867 and 1867–1914). However, with the exception of the Fatimid rule of Egypt, the region was ruled from the Tulunid period (868–905) until 1952 by a succession of individuals who were either of Turkish origin or who had been raised according to the traditions of the Turkish state.[224] Hence, during the Mamluk Sultanate, Arabic sources show that the Bahri period referred to its dynasty as the State of the Turks (Arabic: دولة الاتراك, Dawlat al-Atrāk; دولة الترك, Dawlat al-Turk) or the State of Turkey (الدولة التركية, al-Dawla al-Turkiyya).[225][226] Nonetheless, the Ottoman legacy has been the most significance in the preservation of the Turkish culture in Egypt which still remains visible today.[227]

Lebanon

The Lebanese Turkmen are ethnic Turkmens who constitute one of the ethnic groups in Lebanon. The historic rule of several Turkic dynasties in the region saw continuous Turkish migration waves to Lebanon during the Tulunid rule (868–905), Ikhshidid rule (935–969), Seljuk rule (1037–1194), Mamluk rule (1291–1515), and Ottoman rule (1516–1918). Today, most of the Turkish Lebanese community are the descendants of the Ottoman Turkish settlers to Lebanon from Anatolia. However, with the declining territories of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, ethnic Turkish minorities from other parts of the former Ottoman territories found refuge in Ottoman Lebanon, especially Algerian Turks after the French colonization of North Africa in 1830,[183] and Cretan Turks in 1897 due to unrest in Greece.

Syria

The Turkish-speaking Syrian Turkmen form the second largest ethnic minority group in Syria (i.e., after the Kurds);[94] however, some estimates indicated that if Arabized Turks who no longer speaking Turkish are taken into account then they collectively form the largest ethnic minority in the country.[94] The majority of Syrian Turkmen are the descendants of Anatolian Turkish settlers who arrived in the region during the Ottoman rule (1516–1918). Today, they mostly live near the Syria–Turkey border, stretching from the northwestern governorates of Idlib and Aleppo to the Raqqa Governorate. Many also reside in the Turkmen Mountain near Latakia, the city of Homs and its vicinity until Hama, Damascus, and the southwestern governorates of Dera'a (bordering Jordan) and Quneitra (bordering Israel).[94]

Turkic migrations to Syria began in the 11th century, especially after the Seljuk Turks opened the way for mass migration of Turkish nomads once they entered northern Syria in 1071 and after they took Damascus in 1078 and Aleppo in 1086.[228] By the 12th century the Turkic Zengid dynasty continued to settle Turkmes in Aleppo to confront attacks from the Crusaders.[229] Further migrations occurred once the Mamluks entered Syria in 1260. However, the largest Turkmen migrations occurred after the Ottoman sultan Selim I conquered Syria in 1516. Turkish migration from Anatolia to Ottoman Syria was continuous for almost 400 years, until Ottoman rule ended in 1918.[230]

In 1921 the Treaty of Ankara established Alexandretta (present-day Hatay) under an autonomous regime under French Mandate of Syria. Article 7 declared that the Turkish language would be an officially recognized language.[231] However, once France announced that it would grant full independence to Syria, Mustafa Kemal demanded that Alexandretta be given its independence. Consequently, the Hatay State was established in 1938 and then petitioned for Ankara to unify Hatay with the Republic of Turkey. France agreed to the Turkish annexation on 23 July 1939.[232]

Thereafter, Arabization policies saw the names of Turkish villages in Syria renamed with Arabic names and some Turkmen lands were nationalized and resettled with Arabs near the Turkish border.[233] A mass exodus of Syrian Turkmen took place between 1945 and 1953, many of which settled in southern Turkey.[234] Since the Syrian Civil War (2011–present), many Syrian Turkmen have been internally displaced and many have sought asylum in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon and northern Iraq,[235] as well as several Western European countries[236] and Australia.[89]

Maghreb

The Ottomans took control of Algeria in 1515 and Tunisia in 1534 (but took full control of the latter in 1574) which lead to the settlement of Turks in the region, particularly around the coastal towns. Once these regions came under French colonialism, the French classified the populations under their rule as either "Arab" or "Berber", despite the fact that these countries had diverse populations, which were also composed of ethnic Turks and Kouloughlis (i.e., people of partial Turkish origin). Jane E Goodman has said that:

From early on, the French viewed North Africa through a Manichean lens. Arab and Berber became the primary ethnic categories through which the French classified the population (Lorcin 1995: 2). This occurred despite the fact that a diverse and fragmented populace comprised not only various Arab and Berber tribal groups but also Turks, Andalusians (descended from Moors exiled from Spain during the Crusades), Kouloughlis (offspring of Turkish men and North African women), blacks (mostly slaves or former slaves), and Jews.[237]

Algeria

According to the U.S. Department of State "Algeria's population, [is] a mixture of Arab, Berber, and Turkish in origin";[238] meanwhile, Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs has reported that the demographics of Algeria (as well as that of Tunisia) includes a "strong Turkish admixture".[239]

Today, Turkish descended families in Algeria continue to practice the Hanafi school of Islam (in contrast to the ethnic Arabs and Berbers who practice the Maliki school); moreover, many retain their Turkish-origin surnames — which mostly expresses a provenance or ethnic Turkish origin from Anatolia.[240][241]

Libya

The Turkish Libyans form the second largest ethnic minority group in Libya (i.e. after the Berbers) and mostly live in Misrata, Tripoli, Zawiya, Benghazi and Derna.[101] Some Turkish Libyans also live in more remote areas of the country, such as the Turkish neighborhood of Hay al-Atrak in the town of Awbari.[242] They are the descendants of Turkish settlers who were encouraged to migrate from Anatolia to Libya during the Ottoman rule which lasted between 1555 and 1911.[243]

Today, the city of Misrata is considered to be the "main center of the Turkish-origin community in Libya";[244] in total, the Turks form approximately two-thirds (est. 270,000[245]) of Misrata's 400,000 inhabitants.[245] Consequently, since the Libyan Civil War erupted in 2011, Misrata became "the bastion of resistance" and Turkish Libyans figured prominently in the war.[184] In 2014 a former Gaddafi officer reported to the New York Times that the civil war was now an "ethnic struggle" between Arab tribes (like the Zintanis) against those of Turkish ancestry (like the Misuratis), as well as against the Berbers and Circassians.[246]

Tunisia

Tunisia's population is made up "mostly of people of Arab, Berber, and Turkish descent".[247] The Turkish Tunisians began to settle in the region in 1534, with about 10,000 Turkish soldiers, when the Ottoman Empire answered the calls of Tunisia's inhabitants who sought the help of the Turks due to fears that the Spanish would invade the country.[248] During the Ottoman rule, the Turkish community dominated the political life of the region for centuries; as a result, the ethnic mix of Tunisia changed considerably with the continuous migration of Turks from Anatolia, as well as other parts of the Ottoman territories, for over 300 years. In addition, some Turks intermarried with the local population and their male offspring were called "Kouloughlis".[249]

Europe

Modern immigration of Turks to Western Europe began with Turkish Cypriots migrating to the United Kingdom in the early 1920s when the British Empire annexed Cyprus in 1914 and the residents of Cyprus became subjects of the Crown. However, Turkish Cypriot migration increased significantly in the 1940s and 1950s due to the Cyprus conflict. Conversely, in 1944, Turks who were forcefully deported from Meskheti in Georgia during the Second World War, known as the Meskhetian Turks, settled in Eastern Europe (especially in Russia and Ukraine). By the early 1960s, migration to Western and Northern Europe increased significantly from Turkey when Turkish "guest workers" arrived under a "Labour Export Agreement" with Germany in 1961, followed by a similar agreement with the Netherlands, Belgium and Austria in 1964; France in 1965; and Sweden in 1967.[253][254][255] More recently, Bulgarian Turks, Romanian Turks, and Western Thrace Turks have also migrated to Western Europe.

In 1997 Professor Servet Bayram and Professor Barbara Seels said that there was 10 million Turks living in Western Europe and the Balkans (excluding Cyprus and Turkey).[256] By 2010, Boris Kharkovsky from the Center for Ethnic and Political Science Studies said that there was up to 15 million Turks living in the European Union.[257] According to Dr Araks Pashayan 10 million "Euro-Turks" alone were living in Germany, France, the Netherlands and Belgium in 2012.[258] Yet, there are also significant Turkish communities living in Austria, the UK, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, the Scandinavian countries, and the Post-Soviet states.

North America

In the 2000 United States Census 117,575 Americans voluntarily declared their ethnicity as Turkish.[259] However, the actual number of Turkish Americans is considerably larger with most choosing not to declare their ethnicity. Thus, Turkish Americans have been considered to be a "hard to count" community.[260] In 1996 Professor John J. Grabowski had estimated the number of Turks to be 500,000.[261] By 2009, they numbered approximately 850,000 to 900,000.[262] More recently, in 2012, the US Commerce Secretary, John Bryson, stated that the Turkish American community was over 1,000,000.[15] The largest concentration of Turkish Americans are in New York City, and Rochester, New York; Washington, D.C.; and Detroit, Michigan. In addition, the Turks of South Carolina, are an Anglicized and isolated community identifying as Turkish in Sumter County were they have lived for over 200 years.[263]

Regarding the Turkish Canadian community, Statistics Canada reports that 63,955 Canadians in the 2016 census listed "Turk" as an ethnic origin, including those who listed more than one origin.[264] However, the Canadian Ambassador to Turkey, Chris Cooter, said that there was over 100,000 Turkish Canadians in 2018.[32] The majority live in Ontario, mostly in Toronto, and there is also a sizable Turkish community in Montreal, Quebec.

Oceania

A notable scale of Turkish migration to Australia began in the late 1940s when Turkish Cypriots began to leave the island of Cyprus for economic reasons, and then, during the Cyprus conflict, for political reasons, marking the beginning of a Turkish Cypriot immigration trend to Australia.[265] The Turkish Cypriot community were the only Muslims acceptable under the White Australia Policy;[266] many of these early immigrants found jobs working in factories, out in the fields, or building national infrastructure.[267] In 1967, the governments of Australia and Turkey signed an agreement to allow Turkish citizens to immigrate to Australia.[268] Prior to this recruitment agreement, there were fewer than 3,000 people of Turkish origin in Australia.[269] According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, nearly 19,000 Turkish immigrants arrived from 1968 to 1974.[268] They came largely from rural areas of Turkey, approximately 30% were skilled and 70% were unskilled workers.[270] However, this changed in the 1980s when the number of skilled Turks applying to enter Australia had increased considerably.[270] Over the next 35 years the Turkish population rose to almost 100,000.[269] More than half of the Turkish community settled in Victoria, mostly in the north-western suburbs of Melbourne.[269] According to the 2006 Australian Census, 59,402 people claimed Turkish ancestry;[271] however, this does not show a true reflection of the Turkish Australian community as it is estimated that between 40,000 and 120,000 Turkish Cypriots[272][273][274][275] and 150,000 to 200,000 mainland Turks[276][277] live in Australia. Furthermore, there has also been ethnic Turks who have migrated to Australia from Bulgaria,[278] Greece,[279] Iraq,[280] and North Macedonia.[279]

Post-Soviet states

Due to the ordered deportation of over 115,000 Meskhetian Turks from their homeland in 1944, during the Second World War, the majority were settled in the Post-Soviet states in the Caucasus and Central Asia.[215] According to the 1989 Soviet Census, which was the last Soviet Census, 106,000 Meskhetian Turks lived in Uzbekistan, 50,000 in Kazakhstan, and 21,000 in Kyrgyzstan.[215] However, in 1989, the Meshetian Turks who had settled in Uzbekistan became the target of a pogrom in the Fergana valley, which was the principal destination for Meskhetian Turkish deportees, after an uprising of nationalism by the Uzbeks.[215] The riots had left hundreds of Turks dead or injured and nearly 1,000 properties were destroyed; thus, thousands of Meskhetian Turks were forced into renewed exile.[215] Soviet authorities recorded many Meskhetian Turks as belonging to other nationalities such as "Azeri", "Kazakh", "Kyrgyz", and "Uzbek".[215][281]

Culture

Language

Based on geographic variants, the ethnic Turks speak various dialects of the Turkish language. As of 2021, Turkish remains "the largest and most vigorous Turkic language, spoken by over 80 million people".[282]

Historically, Ottoman Turkish was the official language and lingua franca throughout the Ottoman territories and the Ottoman Turkish alphabet used the Perso-Arabic script. However, Turkish intellectuals sought to simplify the written language during the rise of Turkish nationalism in the nineteenth century.[283]

By the twentieth century, intensive language reforms were thoroughly practiced; most importantly, Mustafa Kemal changed the written script to a Latin-based modern Turkish alphabet in 1928.[284] Since then, the regulatory body leading the reform activities has been the Turkish Language Association which was founded in 1932.[282]

The modern standard Turkish is based on the dialect of Istanbul.[285] However, dialectal variation persists, in spite of the levelling influence of the standard used in mass media and the Turkish education system since the 1930s.[286] The terms ağız or şive often refer to the different types of Turkish dialects.

Official status

Today, the modern Turkish language is used as the official language of Turkey and Northern Cyprus. It is also an official language in the Republic of Cyprus (alongside Greek).[287] In Kosovo, Turkish is recognized as an official language in the municipalities of Prizren, Mamuša, Gjilan, Mitrovica, Pristina, and Vučitrn,[288] whilst elsewhere in the country it is recognized as a minority language.[282] Similarly, in North Macedonia Turkish is an official language where they form at least 20% of the population (which includes the Plasnica Municipality, the Centar Župa Municipality, and the Mavrovo and Rostuša Municipality),[289] whilst elsewhere in the country it remains a minority language only.[282] Iraq recognizes Turkish as an official language in all regions where Turks constitute the majority of the population,[290] and as a minority language elsewhere.[282] In several countries, Turkish is officially recognized as a minority language only, including in Bosnia and Herzegovina,[291] Croatia,[292][293] and Romania.[282][294] However, in Greece the right to use the Turkish language is only recognized in Western Thrace; the sizable and longstanding minorities elsewhere in the country (i.e. Rhodes and Kos) do not benefit from this same recognition.[295]

There are also several post-Ottoman nations which do not officially recognize the Turkish language but give rights to Turkish minorities to study in their own language (alongside the compulsory study of the official language of the country); this is practiced in Bulgaria[296] and Tunisia.[297]

Various variants of Turkish are also used by millions of Turkish immigrants and their descendants in Western Europe, however, there is no official recognition in these countries.[282]

Turkish dialects

There are three major Anatolian Turkish dialect groups spoken in Turkey: the West Anatolian dialect (roughly to the west of the Euphrates), the East Anatolian dialect (to the east of the Euphrates), and the North East Anatolian group, which comprises the dialects of the Eastern Black Sea coast, such as Trabzon, Rize, and the littoral districts of Artvin.[298][299]

The Balkan Turkish dialects, also called the Rumelian Turkish dialects, are divided into two main groups: "Western Rumelian Turkish" and "Eastern Rumelian Turkish".[300] The Western dialects are spoken in North Macedonia, Kosovo, western Bulgaria, northern Romania, Bosnia and Albania. The Eastern dialects are spoken in Greece, northeastern/southern Bulgaria and southeastern Romania.[300] This division roughly follows through a borderline between west and east Bulgaria, which starts east of Lom and proceeds southwards to the east of Vratsa, Sofia and Samokov, and turns west reaching south of Kyustendil close to the Serbian and North Macedonian border.[300] The eastern dialects lacks some of the phonetic peculiarities found in the western area; thus, its dialects are close to the central Anatolian dialects. The Turkish dialects spoken near the western Black Sea region (e.g., Ludogorie, Dobruja, and Bessarabia) show analogies with northeastern Anatolian Black Sea dialects.[300]

The Cypriot Turkish dialect maintained features of the respective local varieties of the Ottoman settlers who mostly came from the Konya-Antalya-Adana region;[300] furthermore, Cypriot Turkish was also influenced by Cypriot Greek.[300] Today, the varieties spoken in Northern Cyprus are increasingly influenced by standard Turkish.The Cypriot Turkish dialect is being exposed to increasing standard Turkish through immigration from Turkey, new mass media, and new educational institutions.[301]

The Iraqi Turkish dialects have similarities with certain Southeastern Anatolian dialects around the region of Urfa and Diyarbakır.[302] Some linguists have described the Iraqi Turkish dialects as an "Anatolian"[303] or an "Eastern Anatolian dialect".[304] Historically, Iraqi Turkish was influenced by Ottoman Turkish and neighboring Azerbaijani Turkic.[305] However, Istanbul Turkish is now a prestige language which exerts a profound influence on their dialects.[306] The syntax in Iraqi Turkish therefore differs sharply from neighboring Irano-Turkic varieties,[306] and shares characteristics which are similar with Turkish dialects in Turkey.[307] Collectively, the Iraqi Turkish dialects also show similarities with Cypriot Turkish and Balkan Turkish regarding modality.[308] The written language of the Iraqi Turkmen is based on Istanbul Turkish using the modern Turkish alphabet.[309]

The Meskhetian Turkish dialect was originally spoken in Georgia until the Turkish Meskhetian community were forcefully deported and then dispersed throughout Turkey, Russia, Central Asia, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, and the United States.[310] They speak an Eastern Anatolian dialect of Turkish, which hails from the regions of Kars, Ardahan, and Artvin.[311] The Meskhetian Turkish dialect has also borrowed from other languages (including Azerbaijani, Georgian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Russian, and Uzbek), which the Meskhetian Turks have been in contact with during the Russian and Soviet rule.[311]

The Syrian Turkish dialects are spoken throughout the country. In Aleppo, Tell Abyad, Raqqa and Bayırbucak they speak Southeastern Anatolian dialects (comparable to Kilis, Antep, Urfa, Hatay and Yayladağı).[312] In Damascus they speak Turkish language with a Yörük dialect.[312] Currently, Turkish is the third most widely used language in Syria (after Arabic and Kurdish).[313]

Religion

Most ethnic Turkish people are either practicing or non-practicing Muslims who follow the teachings of the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam.[81] They form the largest Muslim community in Turkey and Northern Cyprus as well as the largest Muslim groups in Austria,[314] Bulgaria,[315] Czech Republic,[316] Denmark,[317] Germany,[318] Liechtenstein,[319] the Netherlands,[318] Romania[320] and Switzerland.[314] In addition to Sunni Turks, there are Alevi Turks whose local Islamic traditions have been based in Anatolia, as well as the Bektashis traditionally centered in Anatolia and the Balkans.[321]

In general, "Turkish Islam" is considered to be "more moderate and pluralistic" than in other Middle Eastern-Islamic societies.[322] Historically, Turkish Sufi movements promoted liberal forms of Islam;[323] for example, Turkish humanist groups and thinkers, such as the Mevlevis (whirling dervishes who follow Rumi), the Bektashis, and Yunus Emre emphasized faith over practicing Islam.[323] During this tolerant environment under the Seljuk Turks, more Turkish tribes arriving in Anatolia during the 13th century found the liberal Sufi version of Islam closer to their shamanists traditions and chose to preserve some of their culture (such as dance and music).[323] During the late Ottoman period, the Tanzimat policies introduced by the Ottoman intelligentsia fused Islam with modernization reforms; this was followed by Atatürk's secularist reforms in the 20th century.[322]

Consequently, there are also many non-practicing Turkish Muslims who tend to be politically secular. For example, in Cyprus, the Turkish Cypriots are generally very secular and only attend mosques on special occasions (such as for weddings, funerals, and community gatherings).[324] Even so, the Hala Sultan Tekke in Larnaca, which is the resting place of Umm Haram, is considered to be one of the holiest sites in Islam and remains an important pilgrimage site for the secular Turkish Cypriot community too.[325] Similarly, in other urban areas of the Levant, such as in Iraq, the Turkish minority are mainly secular, having internalized the secularist interpretation of state–religion affairs practiced in the Republic of Turkey since its foundation in 1923.[326]

.jpg.webp)

In North Africa, the Turkish minorities have traditionally differentiated themselves from the Arab-Berber population who follow the Maliki school; this is because the Turks have continued to follow the teaching of the Hanafi school which was brought to the region by their ancestors during the Ottoman rule.[327] Indeed, the Ottoman-Turkish mosques in the region are often distinguishable by pencil-like and octagonal minarets which were built in accordance with the traditions of the Hanafi rite.[328][329]

The tradition of building mosques in the Ottoman-style (i.e. either in the imperial style based on Istanbul mosques or the provincial styles) has continued into the present day, both in traditional areas of settlement (e.g. in Turkey, the Balkans, Cyprus, and other parts of the Levant) as well as in Western Europe and North America where there are substantial immigrant communities.[330]

Since the 1960s, "Turkish" was even seen as synonymous with "Muslim" in countries like Germany because Islam was considered to have a specific "Turkish character" and visual architectural style.[331]

Arts and architecture

.jpg.webp)

Turkish architecture reached its peak during the Ottoman period. Ottoman architecture, influenced by Seljuk, Byzantine and Islamic architecture, came to develop a style all of its own.[332] Overall, Ottoman architecture has been described as a synthesis of the architectural traditions of the Mediterranean and the Middle East.[333]

As Turkey successfully transformed from the religion-based former Ottoman Empire into a modern nation-state with a very strong separation of state and religion, an increase in the modes of artistic expression followed. During the first years of the republic, the government invested a large amount of resources into fine arts; such as museums, theatres, opera houses and architecture. Diverse historical factors play important roles in defining the modern Turkish identity. Turkish culture is a product of efforts to be a "modern" Western state, while maintaining traditional religious and historical values.[334] The mix of cultural influences is dramatized, for example, in the form of the "new symbols of the clash and interlacing of cultures" enacted in the works of Orhan Pamuk, recipient of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature.[335] Traditional Turkish music include Turkish folk music (Halk müziği), Fasıl and Ottoman classical music (Sanat müziği) that originates from the Ottoman court.[336] Contemporary Turkish music include Turkish pop music, rock, and Turkish hip hop genres.[336]

Notable people

Namık Kemal, İbrahim Şinasi, Hüseyin Avni Lifij, Faik Ali Ozansoy, Mimar Kemaleddin, İştirakçi Hilmi, Mustafa Suphi, Ethem Nejat, Halid Ziya Uşaklıgil, Rıza Tevfik Bölükbaşı, Latife Uşşaki, Feriha Tevfik, Fatma Aliye Topuz, Keriman Halis Ece, Zeki Rıza Sporel, Cahide Sonku, Süleyman Seyyid, Abdülhak Hâmid Tarhan, Besim Ömer Akalın, Orhan Veli Kanık, Abidin Dino, Ahmet Ziya Akbulut, Nazmi Ziya Güran, Tanburi Büyük Osman Bey, Vecihi Hürkuş, Bedriye Tahir, Halide Edib Adıvar, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Mehmet Emin Yurdakul, Tevfik Fikret, Nâzım Hikmet, Hulusi Behçet, Nuri Demirağ, Fahrelnissa Zeid, Leyla Gencer, Ahmet Ertegün, Metin Oktay, Fikri Alican, Feza Gürsey, Ismail Akbay, Oktay Sinanoğlu, Gazi Yaşargil, Behram Kurşunoğlu, Fethullah Gülen, Mehmet Öz, Tansu Çiller, Cahit Arf, Muhtar Kent, Efe Aydan, Neslihan Demir, Orhan Pamuk and Aziz Sancar.

Genetics

Turkish genomic variation, along with several other Western Asian populations, looks most similar to genomic variation of South European populations such as southern Italians.[337] Data from ancient DNA – covering the Paleolithic, the Neolithic, and the Bronze Age periods – showed that Western Asian genomes, including Turkish ones, have been greatly influenced by early agricultural populations in the area; later population movements, such as those of Turkic speakers, also contributed.[337]

The only whole genome sequencing study of Turkish genetics (on 16 individuals) concluded that the Turkish population forms a cluster with Southern European/Mediterranean populations, and the predicted contribution from ancestral East Asian populations (presumably Central Asian) is 21.7%.[338] However, that is not a direct estimate of a migration rate, due to reasons such as unknown original contributing populations.[338] Moreover, the genetic variation of various populations in Central Asia "has been poorly characterized"; Western Asian populations may also be "closely related to populations in the east".[337] Meanwhile, Central Asia is home to numerous populations that “demonstrate an array of mixed anthropological features of East Eurasians (EEA) and West Eurasians (WEA)”; two studies showed Uyghurs have 40-53% ancestry classified as East Asian, with the rest being classified as European.[339] A 2006 study suggested that the true Central Asian contributions to Anatolia was 13% for males and 22% for females (with wide ranges of confidence intervals), and the language replacement in Turkey and Azerbaijan might not have been in accordance with the elite dominance model.[340]

Another study in 2021, which looked at whole-genomes and whole-exomes of 3,362 unrelated Turkish samples, found "extensive admixture between Balkan, Caucasus, Middle Eastern, and European populations" in line with history of Turkey.[341] Moreover, significant number of rare genome and exome variants were unique to modern-day Turkish population.[341] Neighbouring populations in East and West, and Tuscan people in Italy were closest to Turkish population in terms of genetic similarity.[341] Central Asian contribution to maternal, paternal, and autosomal genes were detected, consistent with the historical migration and expansion of Oghuz Turks from Central Asia.[341] The authors speculated that the genetic similarity of the modern-day Turkish population with modern-day European populations might be due to spread of neolithic Anatolian farmers into Europe, which impacted the genetic makeup of modern-day European populations.[341] Moreover, the study found no clear genetic separation between different regions of Turkey, leading authors to suggest that recent migration events within Turkey resulted in genetic homogenization.[341]

See also

- Tahtacı

- Yörüks

- Turkophilia

- Anti-Turkish sentiment

- Turquerie

- Demographics of Turkey

Notes

^ a: "The history of Turkey encompasses, first, the history of Anatolia before the coming of the Turks and of the civilizations—Hittite, Thracian, Hellenistic, and Byzantine—of which the Turkish nation is the heir by assimilation or example. Second, it includes the history of the Turkish peoples, including the Seljuks, who brought Islam and the Turkish language to Anatolia. Third, it is the history of the Ottoman Empire, a vast, cosmopolitan, pan-Islamic state that developed from a small Turkish amirate in Anatolia and that for centuries was a world power."[342]

^ b: The Turks are also defined by the country of origin. Turkey, once Asia Minor or Anatolia, has a very long and complex history. It was one of the major regions of agricultural development in the early Neolithic and may have been the place of origin and spread of lndo-European languages at that time. The Turkish language was imposed on a predominantly lndo-European-speaking population (Greek being the official language of the Byzantine empire), and genetically there is very little difference between Turkey and the neighboring countries. The number of Turkish invaders was probably rather small and was genetically diluted by the large number of aborigines."

"The consideration of demographic quantities suggests that the present genetic picture of the aboriginal world is determined largely by the history of Paleolithic and Neolithic people, when the greatest relative changes in population numbers took place."[343]

References

- Garibova, Jala (2011), "A Pan-Turkic Dream: Language Unification of Turks", in Fishman, Joshua; Garcia, Ofelia (eds.), Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts, Oxford University Press, p. 268, ISBN 9780199837991,

Approximately 200 million people,... speak nearly 40 Turkic languages and dialects. Turkey is the largest Turkic state, with about 60 million ethnic Turks living in its territories.

- Hobbs, Joseph J. (2017), Fundamentals of World Regional Geography, Cengage, p. 223, ISBN 9781305854956,

The greatest are the 65 million Turks of Turkey, who speak Turkish, a Turkic language...

- "KKTC 2011 NÜFUS VE KONUT SAYIMI" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Orvis, Stephen; Drogus, Carol Ann (2018). Introducing Comparative Politics: Concepts and Cases in Context. CQ Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-5443-7444-4.

Today, nearly three million ethnic Turks live in Germany, and many have raised children there.

- Engstrom, Aineias (12 January 2021), "Turkish-German "dream team" behind first COVID-19 vaccine", Portland State Vanguard, Portland State University, archived from the original on 27 March 2021, retrieved 27 March 2021,

The German census does not gather data on ethnicity, however according to estimates, somewhere between 4–7 million people with Turkish roots, or 5–9% of the population, live in Germany.

- Zestos, George K.; Cooke, Rachel N. (2020), Challenges for the EU as Germany Approaches Recession (PDF), Levy Economics Institute, p. 22,

Presently (2020) more than seven million Turks live in Germany.

- Szyszkowitz, Tessa (2005), "Germany", in Von Hippel, Karin (ed.), Europe Confronts Terrorism, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 53, ISBN 978-0230524590,

It is a little late to start the debate about being an immigrant country now, when already seven million Turks live in Germany.

- Aalberse, Suzanne; Backus, Ad; Muysken, Pieter (2019), Heritage Languages: A language Contact Approach, John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 90, ISBN 978-9027261762,

the Dutch Turkish community... out of a population that over the years must have numbered half a million.

- Tocci, Nathalie (2004), EU Accession Dynamics and Conflict Resolution: Catalysing Peace Or Consolidating Partition in Cyprus?, Ashgate Publishing, p. 130, ISBN 9780754643104,

The Dutch government was concerned about Turkey's reaction to the European Council's conclusions on Cyprus, keeping in mind the presence of two million Turks in Holland and the strong business links with Turkey.

- van Veen, Rita (2007), 'De koningin heeft oog voor andere culturen', Trouw, archived from the original on 12 April 2021, retrieved 25 December 2020,

Erol kan niet voor alle twee miljoen Turken in Nederland spreken, maar hij denkt dat Beatrix wel goed ligt bij veel van zijn landgenoten.

- Baker, Rauf (2021), The Netherlands: The EU's "New Britain"?, Begin–Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, Bar-Ilan University,

The Netherlands, which has a total population of 17 million, contains around two million Turks,...

- Hentz, Jean-Gustave; Hasselmann, Michel (2010). Transculturalité, religion, traditions autour de la mort en réanimation. Springer-Verlag France. doi:10.1007/978-2-287-99072-4_33. ISBN 978-2-287-99072-4.

La France d’aujourd’hui est une société multiculturelle et multiethnique riche de 4,9 millions de migrants représentant environ 8 % de la population du pays. L’immigration massive de populations du sud de l’Europe de culture catholique après la deuxième guerre mondiale a été suivie par l’arrivée de trois millions d’Africains du Nord, d’un million de Turcs et de contingents importants d’Afrique Noire et d’Asie qui ont implanté en France un islam majoritairement sunnite (Maghrébins et Africains de l’Ouest) mais aussi chiite (Pakistanais et Africains de l’Est).

- Gallard, Joseph; Nguyen, Julien (2020), "Il est temps que la France appelle à de véritables sanctions contre le jeu d'Erdogan", Marianne, archived from the original on 14 February 2021, retrieved 25 November 2020,

... et ce grâce à la nombreuse diaspora turque, en particulier en France et en Allemagne. Ils seraient environ un million dans l'Hexagone, si ce n’est plus...es raisons derrière ne sont pas difficiles à deviner : l’immense population turque en Allemagne, estimée par Merkel elle-même aux alentours de sept millions et qui ne manquerait pas de se faire entendre si l’Allemagne prenait des mesures allant à l’encontre de la Turquie.

- Contrat d'objectifs et de moyens (COM) 2020-2022 de France Médias Monde: Mme Joëlle Garriaud-Maylam, co-rapporteur, Sénat, 2021, retrieved 7 May 2021,

Enfin, comme vous l'avez dit au sujet de la Turquie, il est essentiel que la France investisse davantage dans les langues qui sont parlées sur le territoire national. On recense plus d'un million de Turcs en France. Ils ne partagent pas toujours nos objectifs et nos valeurs, parce qu'ils subissent l'influence d'une presse qui ne nous est pas toujours très favorable. Il est donc très utile de les prendre en compte dans le développement de nos médias.

- "Remarks by Commerce Secretary Bryson, April 5, 2012", Foreign Policy Bulletin, Cambridge University Press, 22 (3): 137, 2012,

Here in the U.S., you can see our person-to-person relationships growing stronger each day. You can see it in the 13,000 Turkish students that are studying here in the U.S. You can see it in corporate leaders like Muhtar Kent, the CEO of Coca-Cola, and you can see it in more than one million Turkish-Americans who add to the rich culture and fabric of our country.

- Remarks at Center for American Progress & Confederation of Businessmen and Industrialists of Turkey (TUSKON) Luncheon, U.S. Department of Commerce, 2012, retrieved 13 November 2020

- "UK immigration analysis needed on Turkish legal migration, say MPs". The Guardian. 1 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Federation of Turkish Associations UK (19 June 2008). "Short history of the Federation of Turkish Associations in UK". Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- Warum die Türken? (PDF), vol. 78, Initiative Minderheiten, 2011, archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2021, retrieved 17 August 2021,

Was sind die Gründe für dieses massive Unbehagen angesichts von rund 360.000 Menschen türkischer Herkunft?

- Mölzer, Andreas. "In Österreich leben geschätzte 500.000 Türken, aber kaum mehr als 10–12.000 Slowenen". Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- Manço, Altay; Taş, Ertugrul (2019), "Migrations Matrimoniales: Facteurs de Risque en Sante´ Mentale", The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, SAGE Publishing, 64 (6): 444, doi:10.1177/0706743718802800, PMC 6591757, PMID 30380909

- Debels, Thierry (2021), Operatie Rebel: toen de Belgische heroïnehandel in Turkse handen was, PMagazine, archived from the original on 16 August 2021, retrieved 16 August 2021,

Volgens diverse bronnen zouden eerst een half miljoen Turken die toen in Belgie verbleven – Belgen van Turkse afkomst en aanverwanten – gescreend zijn.

- Lennie, Soraya (2017). "Turkish diaspora in Australia vote in referendum". TRT World. p. 28. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

An estimated 200,000 Turks live in Australia with most of them based in Melbourne's northern suburbs.

- Vahdettin, Levent; Aksoy, Seçil; Öz, Ulaş; Orhan, Kaan (2016), Three-dimensional cephalometric norms of Turkish Cypriots using CBCT images reconstructed from a volumetric rendering program in vivo, Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey,

Recent estimates suggest that there are now 500,000 Turkish Cypriots living in Turkey, 300,000 in the United Kingdom, 120,000 in Australia, 5000 in the United States, 2000 in Germany, 1800 in Canada, and 1600 in New Zealand with a smaller community in South Africa.

- Karcı, Durmuş (2018), "The Effects of Language Characters and Identity of Meskhetian Turkish in Kazakhstan", The Journal of Kesit Academy, 4 (13): 301–303

- Sayıner, Arda (2018). "Swedish touch in Turkey". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- Laczko, Frank; Stacher, Irene; Klekowski von Koppenfels, Amanda (2002), New challenges for Migration Policy in Central and Eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press, p. 187, ISBN 978-90-6704-153-9

- Widding, Lars. "Historik". KSF Prespa Birlik. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Демоскоп Weekly. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 г. Национальный состав населения Российской Федерации. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- Ryazantsev 2009, p. 172.

- Schweizer Nein könnte Europa-Skeptiker stärken, Der Tagesspiegel, 2009, retrieved 26 May 2021,

Dabei erwarten Vertreter der rund 120.000 Türken in der Schweiz nach dem Referendum keine gravierenden Änderungen in ihrem Alltag.

- Aytaç, Seyit Ahmet (2018), Shared issues, stronger ties: Canada's envoy to Turkey, Anadolu Agency, retrieved 7 February 2021,

Turkish diaspora of some 100,000 Turks largely in Toronto is growing, says Canadian Ambassador Chris Cooter ... We have a growing Turkish diaspora and they're doing very well in Canada. We think it's 100,000, largely in Toronto. We have several thousand Turkish students in Canada as well.

- Larsen, Nick Aagaard (2008), Tyrkisk afstand fra Islamisk Trossamfund, Danish Broadcasting Corporation, retrieved 1 November 2020,

Ud af cirka 200.000 muslimer i Danmark har 70.000 tyrkiske rødder, og de udgør dermed langt den største muslimske indvandrergruppe.

- Türk kadınının derdi Danimarka'da da aynı, Milliyet, 2015, retrieved 7 September 2021,

Danimarka’da yaşayan 75 bin Türk nüfusunda,...