Legal Status of Expedited Partner Therapy (EPT)

On This Page

The information presented here is not legal advice, nor is it a comprehensive analysis of all the legal provisions that could implicate the legality of EPT in a given jurisdiction. The data and assessment are intended to be used as a tool to assist state and local health departments as they determine locally appropriate ways to control STDs. The information is not intended to be used for research purposes.

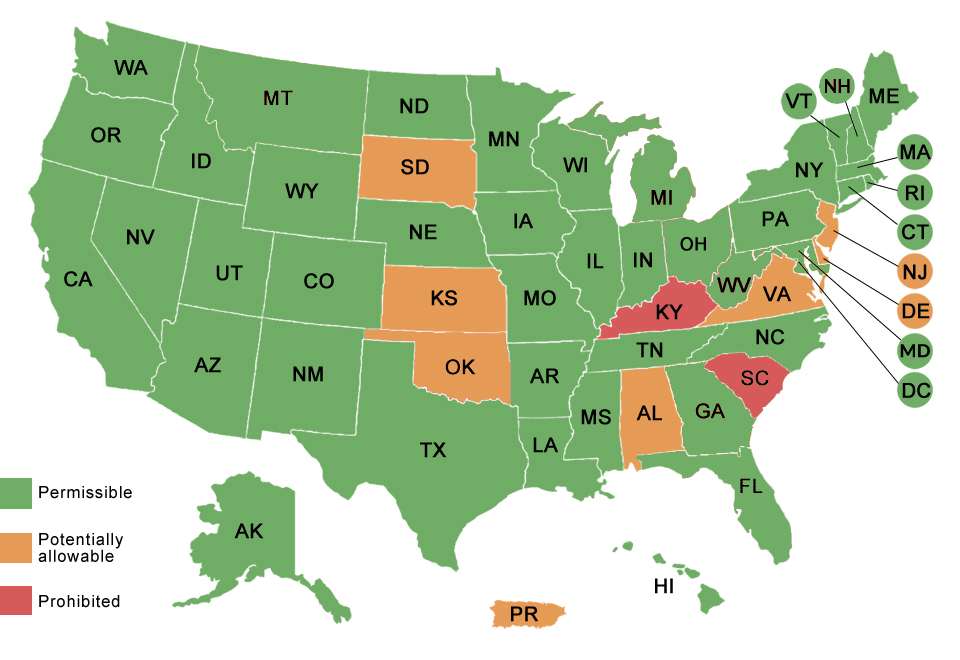

The “status as of” date on every state’s page reflects the most recent date that any law referenced on that page went into effect, even minor changes. To view information for each state, refer to the map or click on a state in the table below. This map is updated on a semiannual basis. It was last updated in July 2017 and will be updated next on/around December 2017. Summary Totals are here.

| Alaska Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Florida Georgia Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Iowa Louisiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Montana Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Mexico New York North Carolina North Dakota Ohio Oregon Pennsylvania Rhode Island Tennessee Texas Utah Vermont Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming EPT is permissible in the District of Columbia. |

Alabama Delaware Kansas New Jersey Oklahoma South Dakota Virginia EPT is potentially allowable in Puerto Rico. |

Kentucky South Carolina |

Introduction

Assuring treatment of the sex partners of persons with sexually transmitted diseases (STD) has been a central component of prevention and control of bacterial STDs in the United States for decades. Traditional practices to inform, evaluate and treat sex partners of persons infected with STDs have relied upon patients or health care providers to notify partners of infected persons of their exposure to an STD. Initially developed to help control syphilis, partner management became widely recommended for gonorrhea, chlamydial infection and, most recently, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. However, for STDs other than syphilis, partner management based on provider referral is rarely assured, while patient referral has had only modest success in assuring partner treatment.

An alternative approach to assuring treatment of partners is expedited partner therapy (EPT). EPT is the delivery of medications or prescriptions by persons infected with an STD to their sex partners without clinical assessment of the partners. Clinicians (e.g., physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, public health workers) provide patients with sufficient medications directly or via prescription for the patients and their partners. After evaluating multiple studies involving EPT, CDC concluded that EPT is a “useful option” to further partner treatment, particularly for male partners of women with chlamydia or gonorrhea. In August 2006, CDC recommended the practice of EPT for certain populations and specific conditions and CDC continues to recommend it in Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010.

Throughout discussions of EPT, the legal status of the practice remained an area of uncertainty. To assist state and local STD programs in their efforts to implement EPT as an additional partner services tool, CDC collaborated with the Center for Law and the Public’s Health at Georgetown and Johns Hopkins Universities to assess the legal framework concerning EPT across all 50 states and other jurisdictions (the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico). The primary research objective was to conceptualize, frame, and identify legal provisions that implicate a clinician’s ability to provide a prescription for a patient’s sex partner, without prior evaluation of that partner, for purposes of treating an STD (specifically chlamydia or gonorrhea). The results of this research, with explanatory information for six key areas of inquiry and summary conclusions for each state are presented here.

The information presented here is not legal advice, nor is it a comprehensive analysis of all the legal provisions that could implicate the legality of EPT in a given jurisdiction. Rather, it provides a comparative snapshot of legal provisions that may highlight legislative, regulatory, judicial laws and policies concerning EPT based on currently available information. This snapshot is subject to change. Measuring the legal weight of non-binding legal sources, such as policy guidance documents or administrative decisions, must be done locally within the context of applicable statutes and regulations. The data and assessment are intended to be used as a tool to assist state and local health departments as they determine locally appropriate ways to control STDs. Assessment of local statutes was not undertaken, with the exception of the District of Columbia. Assessment of tribal laws for sovereign nations was also not undertaken.

Explanation

Sections I – VII categorize key legal provisions implicating EPT as follows:

- Existing statutes/regulations that specifically address the ability of authorized health care providers to provide a prescription for a patient’s partner(s) without prior evaluation for certain STDs. Section I includes statutory or regulatory provisions that specifically address whether a health care provider may provide a prescription for a patient’s partner without a prior evaluation or relationship with the partner. While these provisions may be limited in their application, they may effectually either authorize or prohibit EPT in specific circumstances. For example, a few states feature statutes or regulations that directly authorize some health care professionals to conduct EPT. These laws typically specify the STDs for which EPT is authorized as well as the health care professionals who are authorized to conduct EPT.

- Specific judicial decisions concerning EPT (or like practices). Section II includes judicial decisions (case law) that implicate the legality of EPT or “like practices” (practices that are legally similar to EPT). Case law decisions are legally binding in their jurisdictions and set legal precedent for future decisions.

- Specific administrative opinions by the Attorney General or medical or pharmacy boards concerning EPT (or like practices). Section III includes publicly-available decisions by state administrative bodies that discuss the legality of EPT or like practices. These decisions can include opinions of the state Attorney General, actions by medical disciplinary boards, advisory decisions or resolutions of medical or pharmacy boards, or general policy guidelines. Attorney General opinions are only binding on the party who sought the opinion, but the opinion may indicate how EPT may be regarded in the future.

- Laws that incorporate via reference guidelines as acceptable practices (including EPT). Section V includes legal provisions that allow public health or clinical practices to be incorporated by reference through specific guidelines. Even if the current legal status of EPT in a jurisdiction is unclear, EPT could become legally permissible if a designated published guideline, agency, or official adopted EPT as an acceptable treatment method. The contents of these guidelines are incorporated by reference, which means they have the force of law in that jurisdiction. Legalization of EPT may thus be furthered by consulting with the organization that publishes the guideline or the agency official to recognize EPT as an acceptable treatment method for specific STDs provided such recommendation does not conflict with other legal provisions. The following abbreviations are used in this column of the table:

- “CDC STD Treatment Guidelines” refers to Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines published by CDC through its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports (which explicitly supports the use of EPT for certain STDs and populations);

- “APHA’s CCD Manual” refers to the Control of Communicable Diseases in Man published by the American Public Health Association; and

- “AAP’s Red Book” refers to the Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases published by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Prescription requirements. Section VI includes statutory or regulatory provisions that relate to prescription drug laws (other than for controlled substances) in each jurisdiction to the extent they may impact EPT. This may include:

- laws that require prescription orders or labels to indicate identifying information about the person for whom the prescription is intended. If identifying information is not required, it may facilitate a physician writing a prescription for a patient to deliver to her partner without identifying the partner. While these laws do not necessarily implicate the legality of EPT, they affect how EPT may be implemented in practice. If patient-identifying information is required, a physician may not be legally permitted to provide a blank prescription or an “extra dose” for the patient to deliver to the partner. Instead, such a prescription may have to be made out in the partner’s name;

- laws that concern the pharmacists’ need to verify a physician-patient relationship or that an individual has been examined by a physician prior to dispensing pharmaceutical products; or

- laws that require a pharmacist to ensure that drugs are dispensed to an ultimate user of the prescription.

- Assessment of the legal status of EPT. Section VII provides an assessment whether the various laws of the jurisdiction tend to support or reject the legality of EPT. One of three conclusions is indicated for each jurisdiction:

– EPT is permissible for certain practitioners and conditions;

– EPT is permissible for certain practitioners and conditions;

– EPT is potentially allowable subject to additional actions or policies (this may include specific interpretations of inconsistent or amorphous provisions, supporting policies consistent with legal authorization, or incorporation by reference into treatment guidelines); or

– EPT is potentially allowable subject to additional actions or policies (this may include specific interpretations of inconsistent or amorphous provisions, supporting policies consistent with legal authorization, or incorporation by reference into treatment guidelines); or

– EPT is likely prohibited.Each of these initial conclusions is followed by brief comments providing some justification for the assessment.

– EPT is likely prohibited.Each of these initial conclusions is followed by brief comments providing some justification for the assessment.

Limitations

The information presented here is not legal advice, nor is it a comprehensive analysis of all the legal provisions that could implicate the legality of EPT in a given jurisdiction. Rather, it provides a comparative snapshot of legal provisions that may highlight legislative, regulatory, judicial laws and policies concerning EPT based on currently available information. This snapshot is subject to change. Measuring the legal weight of non-binding legal sources, such as policy guidance documents or administrative decisions, must be done locally within the context of applicable statutes and regulations. The data and assessment are intended to be used as a tool to assist state and local health departments as they determine locally appropriate ways to control STDs. The data and assessment are not intended to be used for research purposes; dates are provided for the most recent legal change regardless of whether it resulted in a changed status. Assessment of local statutes was not undertaken, with the exception of the District of Columbia. Assessment of tribal laws for sovereign nations was also not undertaken.

Related Links

- Page last reviewed: June 29, 2017

- Page last updated: July 3, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir