Diethyl ether

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Ethoxyethane | |

| Other names

Diethyl ether; Dether; Ethyl ether; Ethyl oxide; 3-Oxapentane; Ethoxyethane; Diethyl oxide; Solvent ether; Sulfuric ether; Vitriolic ether; Sweet oil of vitriol | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

Beilstein Reference |

1696894 |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.425 |

| EC Number |

|

Gmelin Reference |

25444 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1155 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

InChI

| |

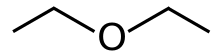

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C4H10O |

| Molar mass | 74.123 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid |

| Odor | Dry, Rum-like, sweetish odor[1] |

| Density | 0.7134 g/cm3, liquid |

| Melting point | −116.3 °C (−177.3 °F; 156.8 K) |

| Boiling point | 34.6 °C (94.3 °F; 307.8 K) [2] |

Solubility in water |

6.05 g/100 mL[3] |

| log P | 0.98[4] |

| Vapor pressure | 440 mmHg at 20 °C (58.66 kPa at 20 °C)[1] |

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

−55.1·10−6 cm3/mol |

Refractive index (nD) |

1.353 (20 °C) |

| Viscosity | 0.224 cP (25 °C) |

| Structure | |

Dipole moment |

1.15 D (gas) |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C) |

172.5 J/mol·K |

Std molar entropy (S |

253.5 J/mol·K |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−271.2 ± 1.9 kJ/mol |

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−2732.1 ± 1.9 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| N01AA01 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Extremely flammable, harmful to skin, decomposes to explosive peroxides in air and light[1] |

| GHS labelling: | |

Pictograms |

|

Signal word |

Danger |

Hazard statements |

H224, H302, H336 |

Precautionary statements |

P210, P233, P240, P241, P242, P243, P261, P264, P270, P271, P280, P301+P312, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P312, P330, P370+P378, P403+P233, P403+P235, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | −45 °C (−49 °F; 228 K) [5] |

Autoignition temperature |

160 °C (320 °F; 433 K)[5] |

| Explosive limits | 1.9–48.0%[6] |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LC50 (median concentration) |

73,000 ppm (rat, 2 hr) 6500 ppm (mouse, 1.65 hr)[7] |

LCLo (lowest published) |

106,000 ppm (rabbit) 76,000 ppm (dog)[7] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 400 ppm (1200 mg/m3)[1] |

REL (Recommended) |

No established REL[1] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

1900 ppm[1] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

| Related compounds | |

Related Ethers |

Dimethyl ether Methoxypropane |

Related compounds |

Diethyl sulfide Butanols (isomer) |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Diethyl ether (data page) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

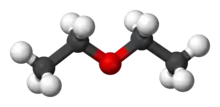

Diethyl ether, or simply ether, is an organic compound in the ether class with the formula (C

2H

5)

2O, sometimes abbreviated as Et

2O (see Pseudoelement symbols). It is a colorless, highly volatile, sweet-smelling ("Ethereal odour"), extremely flammable liquid. It is commonly used as a solvent in laboratories and as a starting fluid for some engines. It was formerly used as a general anesthetic, until non-flammable drugs were developed, such as halothane. It has been used as a recreational drug to cause intoxication.

Production

Most diethyl ether is produced as a byproduct of the vapor-phase hydration of ethylene to make ethanol. This process uses solid-supported phosphoric acid catalysts and can be adjusted to make more ether if the need arises.[8] Vapor-phase dehydration of ethanol over some alumina catalysts can give diethyl ether yields of up to 95%.[9]

Diethyl ether can be prepared both in laboratories and on an industrial scale by the acid ether synthesis.[10] Ethanol is mixed with a strong acid, typically sulfuric acid, H2SO4. The acid dissociates in the aqueous environment producing hydronium ions, H3O+. A hydrogen ion protonates the electronegative oxygen atom of the ethanol, giving the ethanol molecule a positive charge:

- CH3CH2OH + H3O+ → CH3CH2OH2+ + H2O

A nucleophilic oxygen atom of unprotonated ethanol displaces a water molecule from the protonated (electrophilic) ethanol molecule, producing water, a hydrogen ion and diethyl ether.

- CH3CH2OH2+ + CH3CH2OH → H2O + H+ + CH3CH2OCH2CH3

This reaction must be carried out at temperatures lower than 150 °C in order to ensure that an elimination product (ethylene) is not a product of the reaction. At higher temperatures, ethanol will dehydrate to form ethylene. The reaction to make diethyl ether is reversible, so eventually an equilibrium between reactants and products is achieved. Getting a good yield of ether requires that ether be distilled out of the reaction mixture before it reverts to ethanol, taking advantage of Le Chatelier's principle.

Another reaction that can be used for the preparation of ethers is the Williamson ether synthesis, in which an alkoxide (produced by dissolving an alkali metal in the alcohol to be used) performs a nucleophilic substitution upon an alkyl halide.

Uses

It is particularly important as a solvent in the production of cellulose plastics such as cellulose acetate.[8]

Fuel

Diethyl ether has a high cetane number of 85–96 and is used as a starting fluid, in combination with petroleum distillates for gasoline and Diesel engines[11] because of its high volatility and low flash point. Ether starting fluid is sold and used in countries with cold climates, as it can help with cold starting an engine at sub-zero temperatures. For the same reason it is also used as a component of the fuel mixture for carbureted compression ignition model engines. In this way diethyl ether is very similar to one of its precursors, ethanol.

Chemistry

Diethyl ether is a hard Lewis base that reacts with a variety of Lewis acids such as I2, phenol, and Al(CH3)3, and its base parameters in the ECW model are EB = 1.80 and CB = 1.63. Diethyl ether is a common laboratory aprotic solvent. It has limited solubility in water (6.05 g/100 ml at 25 °C[3]) and dissolves 1.5 g/100 g (1.0 g/100 ml) water at 25 °C.[12] This, coupled with its high volatility, makes it ideal for use as the non-polar solvent in liquid-liquid extraction. When used with an aqueous solution, the diethyl ether layer is on top as it has a lower density than the water. It is also a common solvent for the Grignard reaction in addition to other reactions involving organometallic reagents. Due to its application in the manufacturing of illicit substances, it is listed in the Table II precursor under the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances as well as substances such as acetone, toluene and sulfuric acid.[13]

Anesthesia

William T. G. Morton participated in a public demonstration of ether anesthesia on October 16, 1846 at the Ether Dome in Boston, Massachusetts. However, Crawford Williamson Long is now known to have demonstrated its use privately as a general anesthetic in surgery to officials in Georgia, as early as March 30, 1842, and Long publicly demonstrated ether's use as a surgical anesthetic on six occasions before the Boston demonstration.[14][15][16] British doctors were aware of the anesthetic properties of ether as early as 1840 where it was widely prescribed in conjunction with opium.[17] Diethyl ether largely supplanted the use of chloroform as a general anesthetic due to ether's more favorable therapeutic index, that is, a greater difference between an effective dose and a potentially toxic dose.[18]

Diethyl ether does not depress the myocardium but rather it stimulates the sympathetic nervous system leading to hypertension and tachycardia. It is safely used in patients with shock as it preserves the baroreceptor reflex.[19] Its minimal effect on myocardial depression and respiratory drive, as well as its low cost and high therapeutic index allows it to see continued use in developing countries.[20] Diethyl ether could also be mixed with other anesthetic agents such as chloroform to make C.E. mixture, or chloroform and alcohol to make A.C.E. mixture. In the 21st century, ether is rarely used. The use of flammable ether was displaced by nonflammable fluorinated hydrocarbon anesthetics. Halothane was the first such anesthetic developed and other currently used inhaled anesthetics, such as isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane, are halogenated ethers.[21] Diethyl ether was found to have undesirable side effects, such as post-anesthetic nausea and vomiting. Modern anesthetic agents reduce these side effects.[14]

Prior to 2005 it was on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines for use as an anesthetic.[22][23]

Medicine

Ether was once used in pharmaceutical formulations. A mixture of alcohol and ether, one part of diethyl ether and three parts of ethanol, was known as "Spirit of ether", Hoffman's Anodyne or Hoffman's Drops. In the United States this concoction was removed from the Pharmacopeia at some point prior to June 1917,[24] as a study published by William Procter, Jr. in the American Journal of Pharmacy as early as 1852 showed that there were differences in formulation to be found between commercial manufacturers, between international pharmacopoeia, and from Hoffman's original recipe.[25] It is also used to treat hiccups through instillation into nasal cavity.[26]

Recreation

The anesthetic and intoxicating effects of ether have made it a recreational drug. Diethyl ether in anesthetic dosage is an inhalant which has a long history of recreational use. One disadvantage is the high flammability, especially in conjunction with oxygen. One advantage is a well-defined margin between therapeutic and toxic doses, which means one would lose consciousness before dangerous levels of dissolved ether in blood would be reached. With a strong, dense smell, ether causes irritation to respiratory mucosa and is uncomfortable to breathe, and in overdose triggering salivation, vomiting, coughing or spasms. In concentrations of 3–5% in air, an anesthetic effect can slowly be achieved in 15–20 minutes of breathing approximately 15–20 ml of ether, depending on body weight and physical condition. Ether causes a very long excitation stage prior to blacking out.

The recreational use of ether also took place at organised parties in the 19th century called ether frolics, where guests were encouraged to inhale therapeutic amounts of diethyl ether or nitrous oxide, producing a state of excitation. Long, as well as fellow dentists Horace Wells, William Edward Clarke and William T. G. Morton observed that during these gatherings, people would often experience minor injuries but appear to show no reaction to the injury, nor memory that it had happened, demonstrating ether's anaesthetic effects.[27]

In the 19th century and early 20th century ether drinking was popular among Polish peasants.[28] It is a traditional and still relatively popular recreational drug among Lemkos.[29] It is usually consumed in a small quantity (kropka, or "dot") poured over milk, sugar water, or orange juice in a shot glass. As a drug, it has been known to cause psychological dependence, sometimes referred to as etheromania.[30]

Metabolism

A cytochrome P450 enzyme is proposed to metabolize diethyl ether.[31]

Diethyl ether inhibits alcohol dehydrogenase, and thus slows the metabolism of ethanol.[32] It also inhibits metabolism of other drugs requiring oxidative metabolism. For example, diazepam requires hepatic oxidization whereas its oxidized metabolite oxazepam does not.[33]

Safety and stability

Diethyl ether is extremely flammable and may form explosive vapour/air mixtures.[34]

Since ether is heavier than air it can collect low to the ground and the vapour may travel considerable distances to ignition sources, which does not need to be an open flame, but may be a hot plate, steam pipe, heater etc.[34] Vapour may be ignited by the static electricity which can build up when ether is being poured from one vessel into another. The autoignition temperature of diethyl ether is 160 °C (320 °F). The diffusion of diethyl ether in air is 9.18 × 10−6 m2/s (298 K, 101.325 kPa).

Ether is sensitive to light and air, tending to form explosive peroxides.[34] Ether peroxides have a higher boiling point than ether and are contact explosives when dry.[34] Commercial diethyl ether is typically supplied with trace amounts of the antioxidant butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), which reduces the formation of peroxides. Storage over sodium hydroxide precipitates the intermediate ether hydroperoxides. Water and peroxides can be removed by either distillation from sodium and benzophenone, or by passing through a column of activated alumina.[35]

History

The compound may have been synthesised by either Jābir ibn Hayyān in the 8th century[36] or Ramon Llull in 1275.[36][37] It was synthesised in 1540 by Valerius Cordus, who called it "sweet oil of vitriol" (oleum dulce vitrioli)—the name reflects the fact that it is obtained by distilling a mixture of ethanol and sulfuric acid (then known as oil of vitriol)—and noted some of its medicinal properties.[36] At about the same time, Paracelsus discovered the analgesic properties of the molecule in dogs.[36] The name ether was given to the substance in 1729 by August Sigmund Frobenius.[38]

It was considered to be a sulfur compound until the idea was disproved in about 1800. [39]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0277". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ "Diethyl ether". ChemSpider. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- 1 2 Merck Index, 10th Edition, Martha Windholz, editor, Merck & Co., Inc, Rahway, NJ, 1983, page 551

- ↑ "Diethyl ether_msds".

- 1 2 "Ethyl Ether MSDS". J.T. Baker. Archived from the original on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ↑ Carl L. Yaws, Chemical Properties Handbook, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1999, page 567

- 1 2 "Ethyl ether". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- 1 2 "Ethers, by Lawrence Karas and W. J. Piel". Kirk‑Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2004.

- ↑ Ethyl Ether, Chem. Economics Handbook. Menlo Park, Calif: SRI International. 1991.

- ↑ Cohen, Julius Berend (1920). A Class-book of Organic Chemistry, Volume 1. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 39.

the structure of ethyl alcohol cohen julius diethyl ether.

- ↑ "Extra Strength Starting Fluid: How it Works". Valvovine. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ↑ H. H. Rowley; Wm. R. Reed (1951). "Solubility of Water in Diethyl Ether at 25 °". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 73 (6): 2960. doi:10.1021/ja01150a531.

- ↑ Microsoft Word – RedListE2007.doc Archived February 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Hill, John W. and Kolb, Doris K. Chemistry for Changing Times: 10th Edition. p. 257. Pearson: Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. 2004.

- ↑ Madden, M. Leslie (May 14, 2004). "Crawford Long (1815–1878)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. University of Georgia Press. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Crawford W. Long". Doctors' Day. Southern Medical Association. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Grattan, N. "Treatment of Uterine Haemorrhage". Provincial Medicine and Surgical Journal. Vol. 1, No. 6 (Nov. 7, 1840), p. 107.

- ↑ Calderone, F.A. (1935). "Studies on Ether Dosage After Pre-Anesthetic Medication with Narcotics (Barbiturates, Magnesium Sulphate and Morphine)" (PDF). Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 55 (1): 24–39.

- ↑ "Ether effects". 31 October 2010.

- ↑ "Ether and its effects in Anesthesia". 2010-10-31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Morgan, G. Edward, Jr. et al. (2002). Clinical Anesthesiology 3rd Ed. New York: Mc Graw-Hill. p. 3.

- ↑ "Essential Medicines WHO Model List (revised April 2003)" (PDF). apps.who.int (13th ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. April 2003. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ "Essential Medicines WHO Model List (revised March 2005)" (PDF). apps.who.int (14th ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. March 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2005. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ The National druggist, Volume 47, June 1917, pp.220

- ↑ Procter, Jr., William (1852). "On Hoffman's Anodyne Liquor". American Journal of Pharmacy. 28.

- ↑ ncbi, Treatment of hiccups with instillation of ether into nasal cavity.

- ↑ "How Ether Went From a Recreational 'Frolic' Drug to the First Surgery Anesthetic". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ↑ Zandberg, Adrian (2010). "Short Article "Villages … Reek of Ether Vapours": Ether Drinking in Silesia before 1939". Medical History. 54 (3): 387–396. doi:10.1017/s002572730000466x. PMC 2890321. PMID 20592886.

- ↑ Kaszycki, Nestor (2006-08-30). "Łemkowska Watra w Żdyni 2006 – pilnowanie ognia pamięci". Histmag.org – historia od podszewki (in Polish). Kraków, Poland: i-Press. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

Dawniej eteru używało się w lecznictwie do narkozy, ponieważ ma właściwości halucynogenne, a już kilka kropel inhalacji wystarczyło do silnego znieczulenia pacjenta. Jednak eter, jak każda ciecz, może teoretycznie być napojem. Łemkowie tę teorię praktykują. Mimo to, nazywanie skroplonego eteru – "kropki" – ich "napojem narodowym" byłoby przesadą. Chociaż stanowi to pewną część mitu "bycia Łemkiem".

- ↑ Krenz, Sonia; Zimmermann, Grégoire; Kolly, Stéphane; Zullino, Daniele Fabio (August 2003). "Ether: a forgotten addiction". Addiction. 98 (8): 1167–1168. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00439.x. PMID 12873252.

- ↑ 109. Aspergillus flavus mutant strain 241, blocked in aflatoxin biosynthesis, does not accumulate aflR transcript. Matthew P. Brown and Gary A. Payne, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 fgsc.net

- ↑ P. T. Normann; A. Ripel; J. Morland (1987). "Diethyl Ether Inhibits Ethanol Metabolism in Vivo by Interaction with Alcohol Dehydrogenase". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 11 (2): 163–166. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1987.tb01282.x. PMID 3296835.

- ↑ Larry K. Keefer; William A. Garland; Neil F. Oldfield; James E. Swagzdis; Bruce A. Mico (1985). "Inhibition of N-Nitrosodimethylamine Metabolism in Rats by Ether Anesthesia" (PDF). Cancer Research. 45 (11 Pt 1): 5457–60. PMID 4053020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-13. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ W. L. F. Armarego; C. L. L. Chai (2003). Purification of laboratory chemicals. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-7571-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Toski, Judith A; Bacon, Douglas R; Calverley, Rod K (2001). The history of Anesthesiology. In: Barash, Paul G; Cullen, Bruce F; Stoelting, Robert K. Clinical Anesthesia (4 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7817-2268-1.

- ↑ Hademenos, George J.; Murphree, Shaun; Zahler, Kathy; Warner, Jennifer M. (2008-11-12). McGraw-Hill's PCAT. McGraw-Hill. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-07-160045-3. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

- ↑ "VIII. An account of a spiritus vini æthereus, together with several experiments tried therewith". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 36 (413): 283–289. 1730. doi:10.1098/rstl.1729.0045. S2CID 186207852.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 806.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diethyl ether. |

- Michael Faraday's announcement of ether as an anesthetic in 1818

- Calculation of vapor pressure, liquid density, dynamic liquid viscosity, surface tension of diethyl ether, ddbonline.ddbst.de

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards