Romidepsin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Istodax |

| Other names | FK228; FR901228; Istodax |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Histone deacetylase inhibitor[1] |

| Main uses | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs)[2] |

| Side effects | Low white blood cells, low platelets, nausea, tiredness, infection[2] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Intravenous infusion |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| US NLM | Romidepsin |

| MedlinePlus | a610005 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | Not applicable (IV only) |

| Protein binding | 92–94% |

| Metabolism | Liver (mostly CYP3A4-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 3 hours |

| Chemical and physical data | |

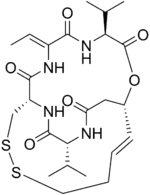

| Formula | C24H36N4O6S2 |

| Molar mass | 540.69 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Romidepsin, sold under the brand name Istodax, is a medication used to treat cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs).[2] It is used after other treatments have failed.[2] It is given by gradual injection into a vein.[3]

Common side effects include low white blood cells, low platelets, nausea, tiredness, and infection.[2] Other side effects may include tumor lysis syndrome and QT prolongation.[3][2] Use during pregnancy may harm the baby.[2] It works by blocking an enzyme known as histone deacetylases, bringing about programmed cell death.[1]

Romidepsin was approved for medical use in the United States in 2009.[3] It was refused approval in Europe in 2012.[4] It is obtained from the bacterium Chromobacterium violaceum.[3] In the United States it costs about 3,350 USD per 10 mg dose.[5] A generic version was approved in 2021 in the USA.[6]

Medical uses

Dosage

The approved dosage of romidepsin in both CTCL and PTCL is a four-hour i.v. administration of 14 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day treatment cycle.[7] This cycle should be repeated as long as the patient continues to benefit and tolerate the therapy. A dose reduction to 10 mg/m2 may be recommended in some who experience high-grade toxicities.

Side effects

The use of romidepsin is uniformly associated with adverse effects.[8] In clinical trials, the most common were nausea and vomiting, fatigue, infection, loss of appetite, and blood disorders (including anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia). It has also been associated with infections, and with metabolic disturbances (such as abnormal electrolyte levels), skin reactions, altered taste perception, and changes in cardiac electrical conduction.[8]

Mechanism of action

Romidepsin acts as a prodrug with the disulfide bond undergoing reduction within the cell to release a zinc-binding thiol.[9][10][11] The thiol binds to a zinc atom in the binding pocket of Zn-dependent histone deacetylase to block its activity. Thus it is an HDAC inhibitor. Many HDAC inhibitors are potential treatments for cancer through the ability to epigenetically restore normal expression of tumor suppressor genes, which may result in cell cycle arrest, differentiation, and apoptosis.[12]

Pharmacodynamics

In a Phase II trial of romidepsin involving patients with CTCL or PTCL, there was evidence of increased histone acetylation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) extending 4–48 hours. Expression of the ABCB1 gene, a marker of romidepsin-induced gene expression, was also increased in both PBMCs and tumor biopsy samples. Increased gene expression following increased histone acetylation is an expected effect of an HDAC inhibitor. Increased hemoglobin F (another surrogate marker for gene-expression changes resulting from HDAC inhibition) was also detected in blood after romidepsin administration, and persistent histone acetylation was inversely associated with drug clearance and directly associated with patient response to therapy.[13]

Pharmacokinetics

In trials involving patients with advanced cancers, romidepsin exhibited linear pharmacokinetics across doses ranging from 1.0 to 24.9 mg/m2 when administered intravenously over four hours.[14] Age, race, sex, mild-to-severe renal impairment, and mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment had no effect on romidepsin pharmacokinetics. No accumulation of plasma concentration was observed after repeated dosing.[15]

History

Romidepsin was first reported in the scientific literature in 1994, by a team of researchers from Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Company (now Astellas Pharma) in Tsukuba, Japan, who isolated it in a culture of Chromobacterium violaceum from a soil sample obtained in Yamagata Prefecture.[9] It was found to have little to no antibacterial activity, but was potently cytotoxic against several human cancer cell lines, with no effect on normal cells; studies on mice later found it to have antitumor activity in vivo as well.[9]

The first total synthesis of romidepsin was accomplished by Harvard researchers and published in 1996.[16] Its mechanism of action was elucidated in 1998, when researchers from Fujisawa and the University of Tokyo found it to be a histone deacetylase inhibitor with effects similar to those of trichostatin A.[17] Romidepsin is branded and owned by Gloucester Pharmaceuticals, now a part of Celgene.[18]

Research

Phase I studies of romidepsin, initially codenamed FK228 and FR901228, began in 1997.[19] Phase II and phase III trials were conducted for a variety of indications. The most significant results were found in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and other peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs).[19]

In 2004, romidepsin received Fast Track designation from the FDA for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and orphan drug status from the FDA and the European Medicines Agency for the same indication.[19]

The FDA approved romidepsin for CTCL in November 2009[20] and approved romidepsin for other peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) in June 2011.[21]

A randomised, phase III trial of romidepsin + CHOP chemotherapy vs CHOP chemotherapy for patients with peripheral T cell lymphoma returned negative results, having no significant impact on progression free survival or overall survival.[22]

HIV

In 2014, PLOS Pathogens published a study involving romidepsin in a trial designed to reactivate latent HIV virus in order to deplete the HIV reservoir. Latently infected T-cells were exposed in vitro and ex vivo to romidepsin, leading to an increase in detectable levels of cell-associated HIV RNA. The trial also compared the effect of romidepsin to another histone deacetylase inhibitor, Vorinostat[23]

Autism

A study involving romidepsin in an animal study that showed that a brief treatment with low amounts of romidepsin could reverse social deficits in a mouse model of autism.[24]

References

- 1 2 "Romidepsin". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 2009-05-09. Retrieved 2009-09-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "DailyMed - ROMIDEPSIN injection, solution, concentrate". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Romidepsin Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ↑ "Istodax". Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ↑ "Istodax Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ↑ Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (10 February 2022). "2021 First Generic Drug Approvals". FDA. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ↑ Nakajima, Hidenori; Kim, Young Bae; Terano, Hiroshi; Yoshida, Minoru; Horinouchi, Sueharu (May 1998). "FR901228, a Potent Antitumor Antibiotic, Is a Novel Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor". Experimental Cell Research. 241 (1): 126–133. doi:10.1006/excr.1998.4027. ISSN 0014-4827. PMID 9633520.

- 1 2 [No authors listed] (October 2014). "ISTODEX Label Information (updated to October 2014)" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-24. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

- 1 2 3 Ueda H, Nakajima H, Hori Y, et al. (March 1994). "FR901228, a novel antitumor bicyclic depsipeptide produced by Chromobacterium violaceum No. 968. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical and biological properties, and antitumor activity". Journal of Antibiotics. 47 (3): 301–10. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.47.301. PMID 7513682.

- ↑ Shigematsu, N.; Ueda, H.; Takase, S.; Tanaka, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Tada, T. (1994). "FR901228, a novel antitumor bicyclic depsipeptide produced by Chromobacterium violaceum No. 968. II. Structure determination". J. Antibiot. 47 (3): 311–314. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.47.311. PMID 8175483.

- ↑ Ueda, H.; Manda, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Mukumoto, S.; Nishigaki, F.; Kawamura, I.; Shimomura, K. (1994). "FR901228, a novel antitumor bicyclic depsipeptide produced by Chromobacterium violaceum No. 968. III. Antitumor activities on experimental tumors in mice". J. Antibiot. 47 (3): 315–323. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.47.315. PMID 8175484.

- ↑ Greshock, Thomas J.; Johns, Deidre M.; Noguchi, Yasuo; Williams, Robert M. (2008). "Improved Total Synthesis of the Potent HDAC Inhibitor FK228 (FR-901228)". Organic Letters. 10 (4): 613–616. doi:10.1021/ol702957z. PMC 3097137. PMID 18205373.

- ↑ Bates, Susan E.; Zhan, Zhirong; Steadman, Kenneth; Obrzut, Tomasz; Luchenko, Victoria; Frye, Robin; Robey, Robert W.; Turner, Maria; Gardner, Erin R. (January 2010). "Laboratory correlates for a phase II trial of romidepsin in cutaneous and peripheral T-cell lymphoma". British Journal of Haematology. 148 (2): 256–267. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07954.x. ISSN 0007-1048. PMC 2838427. PMID 19874311.

- ↑ Bradner, James E; West, Nathan; Grachan, Melissa L; Greenberg, Edward F; Haggarty, Stephen J; Warnow, Tandy; Mazitschek, Ralph (2010-02-07). "Chemical phylogenetics of histone deacetylases". Nature Chemical Biology. 6 (3): 238–243. doi:10.1038/nchembio.313. ISSN 1552-4450. PMC 2822059. PMID 20139990.

- ↑ Nakajima, Hidenori; Kim, Young Bae; Terano, Hiroshi; Yoshida, Minoru; Horinouchi, Sueharu (May 1998). "FR901228, a Potent Antitumor Antibiotic, Is a Novel Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor". Experimental Cell Research. 241 (1): 126–133. doi:10.1006/excr.1998.4027. ISSN 0014-4827. PMID 9633520.

- ↑ Li KW, Wu J, Xing W, Simon JA (July 1996). "Total synthesis of the antitumor depsipeptide FR-901,228". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 118 (30): 7237–8. doi:10.1021/ja9613724.

- ↑ Nakajima H, Kim YB, Terano H, Yoshida M, Horinouchi S (May 1998). "FR901228, a potent antitumor antibiotic, is a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor". Experimental Cell Research. 241 (1): 126–33. doi:10.1006/excr.1998.4027. PMID 9633520.

- ↑ "Romidepsin". Gloucester Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 2009-09-11.

- 1 2 3 Masuoka Y, Shindoh N, Inamura N (2008). "Histone deacetylase inhibitors from microorganisms: the Astellas experience". In Petersen F, Amstutz R (eds.). Natural compounds as drugs. Vol. 2. Basel: Birkhäuser. pp. 335–59. ISBN 978-3-7643-8594-1. Retrieved on November 8, 2009 through Google Book Search.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2021-05-21. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Wei, D; et al. (2014). "Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Romidepsin Induces HIV Expression in CD4 T Cells from Patients on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy at Concentrations Achieved by Clinical Dosing". PLoS Pathog. 10 (4): e1004071. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004071. PMC 3983056. PMID 24722454.

- ↑ Qin, Luye; Ma, Kaijie; Wang, Zi-Jun; Hu, Zihua; Matas, Emmanuel; Wei, Jing; Yan, Zhen (2018). "Social deficits in Shank3-deficient mouse models of autism are rescued by histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition". Nature Neuroscience. 21 (4): 564. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0110-8. PMC 5876144. PMID 29531362.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Clinical trials of romidepsin Archived 2020-09-21 at the Wayback Machine at ClinicalTrials.gov