Tiotropium

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Spiriva, Braltus, others[1] |

| Other names | Tiotropium bromide |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | Inhalation by mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 5 to 10 mcg[3] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604018 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 19.5% (inhalation) |

| Metabolism | Liver 25% (CYP2D6, CYP3A4) |

| Elimination half-life | 5–6 days |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

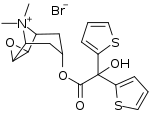

| Formula | C19H22BrNO4S2 |

| Molar mass | 472.41 g·mol−1 |

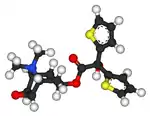

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Tiotropium, sold under the brand name Spiriva among others, is a long-acting bronchodilator used in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma.[5][1] Specifically it is used to try to prevent periods of worsening rather than for those periods themselves.[5] It is used by inhalation through the mouth.[5] Onset typically begins within half an hour and lasts for 24 hours.[5]

Common side effects include a dry mouth, runny nose, upper respiratory tract infection, shortness of breath and headache.[5] Severe side effects may include angioedema, worsening bronchospasm, and QT prolongation.[5] Tentative evidence has not found harm during pregnancy, however, such use has not been well studied.[2] It is an anticholinergic medication and works by blocking acetylcholine action on smooth muscle.[5]

Tiotropium was patented in 1989, and approved for medical use in 2002.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] In the United States the wholesale cost was about US$14 per dose as of 2019.[8] In the United Kingdom a dose costs the NHS about 0.86 pounds as of 2019.[1] In 2017, it was the 82nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than nine million prescriptions.[9][10] There is no generic version available in the United States as of 2019.[11]

Medical uses

Tiotropium is used as maintenance treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[12][13] It may also be used as an add-on therapy in people with moderate-to-severe asthma on medium to high dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).[14][15] It is not however approved for acute exacerbations of COPD or acute worsening of asthma.[5]

Tiotropium is also used in a combination inhaler with olodaterol, a long-acting beta-agonist, for the treatment of COPD, under the trade names Stiolto and Spiolto.

Dosage

For adults it is often used at a dose of 18 mcg once per day.[5]

The defined daily dose is 5 to 10 micrograms by inhalation.[3]

Side effects

Side effects are mainly related to its antimuscarinic effects. Common adverse drug reactions (≥1% of people) include: dry mouth and/or throat irritation. Rarely (<0.1% of patients) treatment is associated with: urinary retention, constipation, acute angle closure glaucoma, palpitations (notably supraventricular tachycardia and atrial fibrillation) and allergy (rash, angioedema, anaphylaxis).[16] A 2006 review found the increase in bronchospasm was small and did not reach statistical significance.[17]

Data regarding some serious side effects is mixed as of 2020.[5] In September 2008 a review found that tiotropium and another member of its class ipratropium may be linked to increased risk of heart attacks, stroke and cardiovascular death.[18] The US FDA reviewed the concern and concluded in 2010 that this association was not supported.[12][19] A 2011 review of the tiotropium mist inhaler (Respimat); however, still found an associated with an increase in all cause mortality in people with COPD.[20]

Mechanism of action

Tiotropium is a muscarinic receptor antagonist, often referred to as an antimuscarinic or anticholinergic agent. Although it does not display selectivity for specific muscarinic receptors, when topically applied it acts mainly on M3 muscarinic receptors[21] located on smooth muscle cells and submucosal glands. This leads to a reduction in smooth muscle contraction and mucus secretion and thus produces a bronchodilatory effect.

Society and culture

Tiotroprium is available in two inhaler formats: a soft mist inhaler (Respimat) and a dry powder inhaler (HandiHaler).[22] The safety and efficacy profiles of both devices are comparable and people's preference should play a role in determining inhaler choice.[22] There is no significant difference in all-cause mortality between tiotropium soft mist inhalers compared to dry powder inhalers, however caution needs to be taken in people with severe heart or kidney problems.[23]

Cost

In the United States the wholesale cost was about US$14 per dose as of 2019.[8] In the United Kingdom a dose costs the NHS about 0.86 pounds as of 2019.[1] In 2017, it was the 82nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than nine million prescriptions.[9][10]

.svg.png.webp) Tiotropium costs (US)

Tiotropium costs (US).svg.png.webp) Tiotropium prescriptions (US)

Tiotropium prescriptions (US)

References

- 1 2 3 4 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 247–248. ISBN 9780857113382.

- 1 2 3 "Tiotropium Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ "Tiotropium (Braltus) 10mcg Inhalation Powder - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 1 February 2019. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Tiotropium Bromide Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 447. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 1 2 "NADAC as of 2019-01-30". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- 1 2 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Tiotropium - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ "Generic Spiriva Availability". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- 1 2 Tashkin, Donald P.; Celli, Bartolome; Senn, Stephen; Burkhart, Deborah; Kesten, Steven; Menjoge, Shailendra; Decramer, Marc (9 October 2008). "A 4-Year Trial of Tiotropium in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (15): 1543–1554. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0805800. hdl:2437/111564. PMID 18836213.

- ↑ Pocket Guide to COPD Diagnosis, Management and Prevention [Internet] Fontana, WI The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2020 [Cited 12/04/2020] Available from: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/GOLD-2020-POCKET-GUIDE-ver1.0_FINAL-WMV.pdf Archived 12 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Rodrigo, Gustavo J.; Castro-Rodríguez, José A. (February 2015). "What Is the Role of Tiotropium in Asthma?". Chest. 147 (2): 388–396. doi:10.1378/chest.14-1698. PMID 25322075.

- ↑ Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (2020 update) (PDF). GOLD. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ Rossi S, ed. (2006). Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide.

- ↑ Kesten, S; Jara, M; Wentworth, C; Lanes, S (December 2006). "Pooled clinical trial analysis of tiotropium safety". Chest. 130 (6): 1695–703. doi:10.1378/chest.130.6.1695. PMID 17166984.

- ↑ Singh, Sonal; Loke, YK; Furberg, CD (24 September 2008). "Inhaled Anticholinergics and Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease". JAMA. 300 (12): 1439–50. doi:10.1001/jama.300.12.1439. PMID 18812535.

- ↑ "Follow-Up to the October 2008 Updated Early Communication about an Ongoing Safety Review of Tiotropium (marketed as Spiriva HandiHaler)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 14 January 2010. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ Singh, S; Loke, YK; Enright, PL; Furberg, CD (14 June 2011). "Mortality associated with tiotropium mist inhaler in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 342: d3215. doi:10.1136/bmj.d3215. PMC 3114950. PMID 21672999.

- ↑ Kato, Mahoto; Komamura, Kazuo; Kitakaze, Masafumi (2006). "Tiotropium, a Novel Muscarinic M3 Receptor Antagonist, Improved Symptoms of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Complicated by Chronic Heart Failure". Circulation Journal. 70 (12): 1658–1660. doi:10.1253/circj.70.1658. PMID 17127817.

- 1 2 Dahl, Ronald; Kaplan, Alan (11 October 2016). "A systematic review of comparative studies of tiotropium Respimat® and tiotropium HandiHaler® in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: does inhaler choice matter?". BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 16 (1): 135. doi:10.1186/s12890-016-0291-4. PMC 5057252. PMID 27724909.

- ↑ Wise, Robert A.; Anzueto, Antonio; Cotton, Daniel; Dahl, Ronald; Devins, Theresa; Disse, Bernd; Dusser, Daniel; Joseph, Elizabeth; Kattenbeck, Sabine; Koenen-Bergmann, Michael; Pledger, Gordon; Calverley, Peter (17 October 2013). "Tiotropium Respimat Inhaler and the Risk of Death in COPD". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (16): 1491–1501. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1303342. PMID 23992515.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- "Tiotropium bromide". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

.png.webp)