Catheter ablation

| Catheter ablation | |

|---|---|

| |

Catheter ablation is a procedure used to remove or terminate a faulty electrical pathway from sections of the heart of those who are prone to developing cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. If not controlled, such arrhythmias increase the risk of ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac arrest. The ablation procedure can be classified by energy source: radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation.

Medical uses

Catheter ablation may be recommended for a recurrent or persistent arrhythmia resulting in symptoms or other dysfunction. Typically, catheter ablation is used only when pharmacologic treatment has been ineffective.

Effectiveness

Catheter ablation of most arrhythmias has a high success rate. Success rates for WPW syndrome have been as high as 95% [1] For SVT, single procedure success is 91% to 96% (95% Confidence Interval) and multiple procedure success is 92% to 97% (95% Confidence Interval).[2] For atrial flutter, single procedure success is 88% to 95% (95% Confidence Interval) and multiple procedure success is 95% to 99% (95% Confidence Interval).[2] For automatic atrial tachycardias, the success rates are 70–90%. The potential complications include bleeding, blood clots, pericardial tamponade, and heart block, but these risks are very low, ranging from 2.6 to 3.2%.

For non-paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, a 2016 systematic review compared catheter ablation to heart rhythm drugs. After 12 months, participants receiving catheter ablation were more likely to be free of atrial fibrillation, and less likely to need cardioversion. However, the evidence quality ranged from moderate to very low[3] A 2006 study, including both paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, found that the success rates are 28% for single procedures. Often, several procedures are needed to raise the success rate to a 70–80% range.[4] One reason for this may be that once the heart has undergone atrial remodeling as in the case of chronic atrial fibrillation patients, largely 50 and older, it is much more difficult to correct the 'bad' electrical pathways. Young people with AF with paroxysmal, or intermittent, AF therefore have an increased chance of success with an ablation since their heart has not undergone atrial remodeling yet. Several experienced teams of electrophysiologists in US heart centers claim they can achieve up to a 75% success rate.

Pulmonary vein isolation has been found to be more effective than optimized antiarrhythmic drug therapy for improving quality of life at 12 months after treatment. [5]

Technique

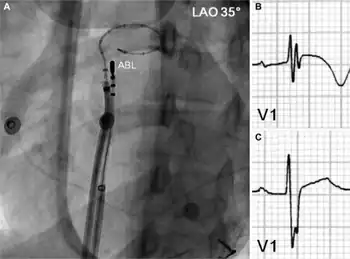

Catheter ablation involves advancing several flexible catheters into the patient's blood vessels, usually either in the femoral vein, internal jugular vein, or subclavian vein. The catheters are then advanced towards the heart. Electrical impulses are then used to induce the arrhythmia and local heating or freezing is used to ablate (destroy) the abnormal tissue that is causing it. Originally, a DC impulse was used to create lesions in the intra-cardiac conduction system.[6] However, due to a high incidence of complications, widespread use was never achieved. Newer procedures allow for the terminating of diseased or dying tissue to reduce the chance of arrhythmia.

One type of catheter ablation is pulmonary vein isolation, where the ablation is done in the left atrium in the area where the 4 pulmonary veins connect.[7][8]

Catheter ablation is usually performed by an electrophysiologist (a specially trained cardiologist) in a cath lab or a specialized EP lab.

Recovery or rehabilitation

After catheter ablation the patients are moved to a cardiac recovery unit, intensive care unit, or cardiovascular intensive care unit where they are not allowed to move for 4–6 hours. Minimizing movement helps prevent bleeding from the site of catheter insertion. Some people have to stay overnight for observation, some need to stay much longer and others are able to go home on the same day. This all depends on the problem, the length of the operation and whether or not general anaesthetic was used.

References

- ↑ Thakur RK, Klein GJ, Yee R (September 1994). "Radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome". CMAJ. 151 (6): 771–6. PMC 1337132. PMID 8087753.

- 1 2 Spector P, Reynolds MR, Calkins H, Sondhi M, Xu Y, Martin A, Williams CJ, Sledge I (September 2009). "Meta-analysis of ablation of atrial flutter and supraventricular tachycardia". Am. J. Cardiol. 104 (5): 671–7. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.04.040. PMID 19699343.

- ↑ Nyong, Jonathan; Amit, Guy; Adler, Alma J; Owolabi, Onikepe; Perel, Pablo; Prieto-Merino, David; Lambiase, Pier; Casas, Juan Pablo; Morillo, Carlos A (November 2016). "Efficacy and safety of ablation for people with non-paroxysmal atrial fibrillation". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (11): CD012088. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012088.pub2. PMC 6464287. PMID 27871122. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ↑ Cheema A, Vasamreddy CR, Dalal D, Marine JE, Dong J, Henrikson CA, Spragg D, Cheng A, Nazarian S, Sinha S, Halperin H, Berger R, Calkins H (April 2006). "Long-term single procedure efficacy of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation". J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 15 (3): 145–55. doi:10.1007/s10840-006-9005-9. PMID 17019636. S2CID 7846706.

- ↑ Blomström-Lundqvist, Carina; Gizurarson, Sigfus; Schwieler, Jonas; Jensen, Steen M.; Bergfeldt, Lennart; Kennebäck, Göran; Rubulis, Aigars; Malmborg, Helena; Raatikainen, Pekka; Lönnerholm, Stefan; Höglund, Niklas; Mörtsell, David (19 March 2019). "Effect of Catheter Ablation vs Antiarrhythmic Medication on Quality of Life in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: The CAPTAF Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA. 321 (11): 1059–1068. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.0335. PMID 30874754. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ Beazell JW, Adomian GE, Furmanski M, Tan KS (December 1982). "Experimental production of complete heart block by electrocoagulation in the closed chest dog". Am. Heart J. 104 (6): 1328–34. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(82)90163-6. PMID 7148651.

- ↑ Keane, D; Ruskin, J (Fall 2002). "Pulmonary vein isolation for atrial fibrillation". Rev Cardiovasc Med. 3 (4): 167–175. PMID 12556750. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ↑ "Pulmonary vein isolation". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.