Left atrial appendage occlusion

| Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion | |

|---|---|

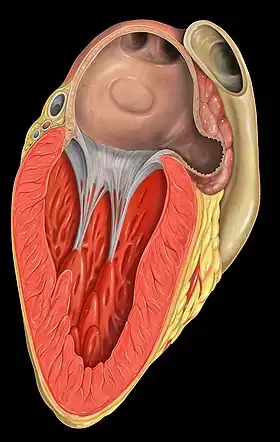

The left atrial appendage is the windsock-like structure shown to originate from the left atrium (3 o'clock). | |

| ICD-9-CM | 37.36 |

Left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO), also referred to as Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) is a treatment strategy to reduce the risk of left atrial appendage blood clots from entering the bloodstream and causing a stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF).

In non-valvular AF, over 90% of stroke-causing clots that come from the heart are formed in the left atrial appendage.[1] The most common treatment for AF stroke risk is treatment with blood-thinning medications, also called oral anticoagulants, which reduce the chance for blood clots to form. These medications (which include warfarin, and other newer approved blood thinners) are very effective in lowering the risk of stroke in AF patients. Most patients can safely take these medications for years (and even decades) without serious side effects.

However, some patients find that blood thinning medications can be difficult to tolerate or are risky. Because they prevent blood clots by thinning the blood, blood thinners can increase the risk of bleeding problems. In select patients, physicians determine that an alternative to blood thinners is needed to reduce AF stroke risk. Approximately 45% of patients who are eligible for warfarin are not being treated, due to tolerance or adherence issues.[2] This applies particularly to the elderly, although studies have indicated that they can also benefit from anticoagulants.[3]

Left atrial appendage closure is an implant-based alternative to blood thinners. Like blood thinning medications, an LAAC implant does not cure AF. A stroke can be due to factors not related to a clot traveling to the brain from the left atrium. Other causes of stroke can include high blood pressure and narrowing of the blood vessels to the brain. An LAAC implant will not prevent these other causes of stroke.

Devices and alternatives

Strategy Occlusion of the left atrial appendage can be achieved from an outside perspective (the #Lariat device) or an inside (endovascular) blood exposed device (#Watchman first in this endeavor). The first method (ligation) eliminates perfusion of the LAA altogether. While effective in preventing many embolic strokes, it also negates endocrine contribution of the LAA. The second approach has many hazards as well but preserves cardiac endocrine properties of the LAA. Further evaluation of both approaches is merited.

On March 13, 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the WATCHMAN™ LAAC Implant, from Boston Scientific, to reduce the risk of thromboembolism from the left atrial appendage in patients with non-valvular AF who are at increased risk of stroke and are recommended for blood thinning medicines, are suitable for warfarin and have an appropriate reason to seek a non-drug alternative to warfarin. The Watchman implant was studied in two randomized clinical trials and several clinical registries.[4] The implant was approved in Europe in 2009.[5]

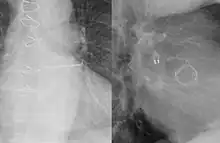

The WATCHMAN Implant is a one-time implant typically performed under general anesthesia with Transesophageal echo guidance (TEE). Similar to a stent procedure, the device is guided into the heart through a flexible tube (catheter) inserted through the femoral vein in the upper leg. The implant is introduced into the right atrium and is then passed into the left atrium through a puncture hole.[6] These small iatrogenic atrial septal defects usually disappear within six months.[7][8] Once the position is confirmed, the implant is released and is left permanently fixed in the heart. The implant does not require open heart surgery and does not need to be replaced. Recovery typically takes twenty-four hours.[6]

The patient continues taking warfarin with aspirin for 45 days post implantation at which point in time they return for a transesophageal echocardiography to judge completeness of the closure and the presence of blood clots. If the seal is complete (no gaps around the device larger than 5mm with communication to the appendage), then the patient can stop taking warfarin and start clopidogrel and aspirin for 6 months after implant. At 6 months post implantation, it is recommended for the patient to continue taking aspirin indefinitely.[6] In the PREVAIL clinical trial, 92% of patients stopped taking warfarin after 45 days and 99% discontinued warfarin at 1 year.[9]

Another device termed PLAATO (percutaneous left atrial appendage transcatheter occlusion) was the first LAA occlusion device,[10][11] although it is no longer being developed by its manufacturer (Appriva Medical, Inc. from Sunnyvale, CA). In 210 patients receiving the PLAATO device, there was an estimated 61% reduction in the calculated stroke risk.[12]

The Amplatzer device from St. Jude Medical, used to close atrial septal defects, has also been used to occlude the left atrial appendage.[13][14] This can be performed without general anaesthesia and without echocardiographic guidance. Transcatheter patch obliteration of the LAA has also been reported.[7]

The ULTRASEAL LAA device, from Cardia, is a percutaneous, transcatheter device intended to prevent thrombus embolization from the left atrial appendage in patients who have non-valvular atrial fibrillation. As with all Cardia devices (such as: Atrial Septal Defect Closure Device or Patent Foramen Ovale Closure Device), the Ultraseal is fully retrievable and repositionable in the Cardia Delivery System used for deployment. The device can be retrieved and redeployed multiple times in a single procedure without replacing the device or delivery sheath.

Other devices exist to occlude the left atrial appendage from the inside of the heart such as the Wavecrest device[15] and the Lariat device.[16] The latter technique entails closing a strangling noose around the LAA, which is advanced from the chest wall with a special sheath, after introducing a balloon in the LAA from the inside surface of the heart (endocardium).

The LAA can also be surgically removed simultaneous with other cardiac procedures such as the maze procedure or during mitral valve surgery; specifically it can be occluded or excluded by over-sewing, excision and resection, ligation, stapling with or without amputation of the LAA or application of a clip system [17][18][19] Finally, the left atrial appendage has been closed in a limited number of patients using a chest keyhole surgery approach.[20][21]

Adverse events

The main adverse events related to this procedure are pericardial effusion, incomplete LAA closure, dislodgement of the device, blood clot formation on the device requiring prolonged oral anticoagulation, and the general risks of catheter-based techniques (such as air embolism).[22] The left atrium anatomy can also preclude use of the device in some patients.[23]

Theoretical concerns surround the role of the LAA in thirst regulation and water retention because it is an important source of atrial natriuretic factor.[24][25] Preserving the right atrial appendage might attenuate this effect.[26]

Footnotes

- ↑ Blackshear JL, Odell JA (February 1996). "Appendage obliteration to reduce stroke in cardiac surgical patients with atrial fibrillation". Ann. Thorac. Surg. 61 (2): 755–9. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(95)00887-X. PMID 8572814.

- ↑ Jani, et al(April 2014). "Uptake of Novel Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with Non-Valvular and Valvular Atrial Fibrillation: Results from the NCDR-Pinnacle Registry" J Am Coll Cardiol 63 (12). Table 1.

- ↑ Mant J, Hobbs FD, Fletcher K, et al. (August 2007). "Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 370 (9586): 493–503. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61233-1. PMID 17693178.

- ↑ WATCHMAN LAA Closure Technology – P130013. (US Food and Drug Administration), April 2015.

- ↑ P De Backer O, Arnous S, Ihlemann N, et al. (April 2014). "Percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: an update". Open Heart. 1 (e000020): e000020. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2013-000020. PMC 4195925. PMID 25332785.

- 1 2 3 WATCHMAN Left Atrial Appendage Closure Device with Delivery System Archived 2015-06-24 at the Wayback Machine. 14 (Boston Scientific), March 2015.

- 1 2 Onalan O, Crystal E (February 2007). "Left atrial appendage exclusion for stroke prevention in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation". Stroke. 38 (2 Suppl): 624–30. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000250166.06949.95. PMID 17261703.

- ↑ Schmidt H, Hammerstingl C, von der Recke G, Hardung D, Omran H (2006). "Long-term follow-up in patients with percutaneous left atrial appendage transcatheter occlusion system (PLAATO): risk of thrombus formation and development of pulmonary venous obstruction after percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47: 36A.

- ↑ Holmes D, et al. (July 2014). "Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 64 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.029. PMID 24998121.

- ↑ Sievert H, Lesh MD, Trepels T, et al. (April 2002). "Percutaneous left atrial appendage transcatheter occlusion to prevent stroke in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation: early clinical experience". Circulation. 105 (16): 1887–9. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000015698.54752.6D. PMID 11997272.

- ↑ Ostermayer SH, Reisman M, Kramer PH, et al. (July 2005). "Percutaneous left atrial appendage transcatheter occlusion (PLAATO system) to prevent stroke in high-risk patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation: results from the international multi-center feasibility trials". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 46 (1): 9–14. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.042. PMID 15992628.

- ↑ Bayard Y, Omran H, Kramer P, et al. (2005). "Worldwide experience of percutaneous left atrial appendage transcatheter occlusion (PLAATO)"". J. Neurol. Sci. 238: S70. doi:10.1016/s0022-510x(05)80271-0.

- ↑ Meier B, Palacios I, Windecker S, et al. (November 2003). "Transcatheter left atrial appendage occlusion with Amplatzer devices to obviate anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation". Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 60 (3): 417–22. doi:10.1002/ccd.10660. PMID 14571497.

- ↑ Nietlispach F, Gloekler S, Krause R, Shakir S, Schmid M, Khattab AA, Wenaweser P, Windecker S, Meier B (2013). "Amplatzer left atrial appendage occlusion: Single center 10-year experience". Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 82 (2): 283–289. doi:10.1002/ccd.24872. PMID 23412815.

- ↑ Cheng Yanping; McGregor Jenn; Sommer Robert (2012). "TCT-764 Safety and Biocompatibility of the Coherex WaveCrest™ Left Atrial Appendage Occluder in a 30-Day Canine Study". J Am Coll Cardiol. 60 (17S): B222–B223. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.807.

- ↑ Bartus K, Han FT, Bednarek J (Jul 2013). "Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Suture Ligation Using the LARIAT Device in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Initial Clinical Experience". J Am Coll Cardiol. 62 (2): 108–18. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.046.

- ↑ Crystal E, Lamy A, Connolly SJ, et al. (January 2003). "Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Study (LAAOS): a randomized clinical trial of left atrial appendage occlusion during routine coronary artery bypass graft surgery for long-term stroke prevention". Am. Heart J. 145 (1): 174–8. doi:10.1067/mhj.2003.44. PMID 12514671.

- ↑ Healey JS, Crystal E, Lamy A, et al. (August 2005). "Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Study (LAAOS): results of a randomized controlled pilot study of left atrial appendage occlusion during coronary bypass surgery in patients at risk for stroke". Am. Heart J. 150 (2): 288–93. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2004.09.054. PMID 16086933.

- ↑ Thorsten Hanke, Surgical management of the left atrial appendage: a must or a myth?, European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Volume 53, Issue suppl_1, April 2018, Pages i33–i38, https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezy088

- ↑ Johnson WD, Ganjoo AK, Stone CD, Srivyas RC, Howard M (June 2000). "The left atrial appendage: our most lethal human attachment! Surgical implications". Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 17 (6): 718–22. doi:10.1016/S1010-7940(00)00419-X. PMID 10856866.

- ↑ Blackshear JL, Johnson WD, Odell JA, et al. (October 2003). "Thoracoscopic extracardiac obliteration of the left atrial appendage for stroke risk reduction in atrial fibrillation". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 42 (7): 1249–52. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00953-7. PMID 14522490.

- ↑ Sick PB, Schuler G, Hauptmann KE, et al. (April 2007). "Initial worldwide experience with the WATCHMAN left atrial appendage system for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49 (13): 1490–5. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.035. PMID 17397680.

- ↑ Fountain R, Holmes DR, Hodgson PK, Chandrasekaran K, Van Tassel R, Sick P (October 2006). "Potential applicability and utilization of left atrial appendage occlusion devices in patients with atrial fibrillation". Am. Heart J. 152 (4): 720–3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2006.05.001. PMID 16996847.

- ↑ Zimmerman MB, Blaine EH, Stricker EM (January 1981). "Water intake in hypovolemic sheep: effects of crushing the left atrial appendage". Science. 211 (4481): 489–91. doi:10.1126/science.7455689. PMID 7455689.

- ↑ Yoshihara F, Nishikimi T, Kosakai Y, et al. (August 1998). "Atrial natriuretic peptide secretion and body fluid balance after bilateral atrial appendectomy by the maze procedure". J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 116 (2): 213–9. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70119-9. PMID 9699572.

- ↑ Omari BO, Nelson RJ, Robertson JM (August 1991). "Effect of right atrial appendectomy on the release of atrial natriuretic hormone". J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 102 (2): 272–9. PMID 1830916.