Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Churg–Strauss syndrome, allergic angiitis and granulomatosis.[1] | |

| |

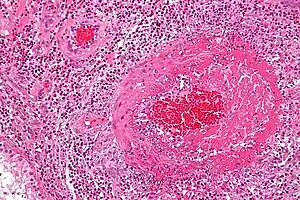

| Micrograph showing an eosinophilic vasculitis consistent with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. H&E stain. One of the American College of Rheumatology criteria for EGPA is extravascular eosinophil infiltration on biopsy.[2] | |

| Symptoms | Fatigue, fever, weight loss, night sweats, abdominal pain, cough, joint pain, muscle pain, bleeding into tissues under the skin, a rash with hives, small bumps, or a general feeling of ill.[1] |

| Complications | hypereosinophilia, granulomatosis, vasculitis, inner ear infections with fluid build up, inflammation of the moist membrane lining the surface of the eyelids, or inflammation of peripheral nerves.[1] |

| Risk factors | History of allergy, asthma and asthma-associated lung abnormalities (i.e., pulmonary infiltrates).[1] |

| Diagnostic method | antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA); cluster of asthma, eosinophilia, mono- or polyneuropathy, nonfixed pulmonary infiltrates, abnormality of the paranasal sinuses, and extravascular eosinophilia.[1] |

| Treatment | Suppress the activity of the immune system to alleviate inflammation.[1] |

| Medication | Corticosteroid medications such as prednisone or methylprednisolone, and mepolizumab.[1] Proliferation inhibitor for those with the presence of kidney or neurological disease.[1] |

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), formerly known as allergic granulomatosis,[3][4] is an extremely rare autoimmune condition that causes inflammation of small and medium-sized blood vessels (vasculitis) in persons with a history of airway allergic hypersensitivity (atopy).[5]

It usually manifests in three stages. The early (prodromal) stage is marked by airway inflammation; almost all patients experience asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. The second stage is characterized by abnormally high numbers of eosinophils (hypereosinophilia), which causes tissue damage, most commonly to the lungs and the digestive tract.[5] The third stage consists of vasculitis, which can eventually lead to cell death and can be life-threatening.[5]

This condition is now called "eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis" to remove all eponyms from the vasculitides. To facilitate the transition, it was referred to as "eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss)" for a period of time starting in 2012.[6] Prior to this it was known as "Churg–Strauss syndrome", named after Drs. Jacob Churg and Lotte Strauss who, in 1951, first published about the syndrome using the term "allergic granulomatosis" to describe it.[3] It is a type of systemic necrotizing vasculitis.

Effective treatment of EGPA requires suppression of the immune system with medication. This is typically glucocorticoids, followed by other agents such as cyclophosphamide or azathioprine.

Signs and symptoms

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis consists of three stages, but not all patients develop all three stages or progress from one stage to the next in the same order;[7] whereas some patients may develop severe or life-threatening complications such as gastrointestinal involvement and heart disease, some patients are only mildly affected, e.g. with skin lesions and nasal polyps.[8] EGPA is consequently considered a highly variable condition in terms of its presentation and its course.[7][8]

.jpg.webp) Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis.jpg.webp) Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Allergic stage

The prodromal stage is characterized by allergy. Almost all patients experience asthma and/or allergic rhinitis,[9] with more than 90% having a history of asthma that is either a new development, or the worsening of pre-existing asthma,[10] which may require systemic corticosteroid treatment.[7] On average, asthma develops from three to nine years before the other signs and symptoms.[7]

The allergic rhinitis may produce symptoms such as rhinorrhea and nasal obstruction, and the formation of nasal polyps that require surgical removal, often more than once.[9] Sinusitis may also be present.[9]

Eosinophilic stage

The second stage is characterized by an abnormally high level of eosinophils (a type of white blood cell) in the blood and tissues as a result of abnormal eosinophil proliferation, impaired eosinophil apoptosis, and increased toxicity due to eosinophil metabolic products.[7][11] The symptoms of hypereosinophilia depend on which part of the body is affected, but most often it affects the lungs and digestive tract.[7] The signs and symptoms of hypereosinophilia may include weight loss, night sweats, asthma, cough, abdominal pain, and gastrointestinal bleeding.[7] Fever and malaise are often present.[12]

The eosinophilic stage can last months or years, and its symptoms can disappear, only to return later.[7] Patients may experience the third stage simultaneously.[7]

Vasculitic stage

The third and final stage, and hallmark of EGPA, is inflammation of the blood vessels, and the consequent reduction of blood flow to various organs and tissues.[7] Local and systemic symptoms become more widespread and are compounded by new symptoms from the vasculitis.[12]

Severe complications may arise. Blood clots may develop within the damaged arteries in severe cases, particularly in arteries of the abdominal region, which is followed by infarction and cell death, or slow atrophy.[12] Many patients experience severe abdominal complaints; these are most often due to peritonitis and/or ulcerations and perforations of the gastrointestinal tract, but occasionally due to acalculous cholecystitis or granulomatous appendicitis.[12]

The most serious complication of the vasculitic stage is heart disease, which is the cause of nearly one-half of all deaths in patients with EGPA.[12] Among heart disease-related deaths, the most usual cause is inflammation of the heart muscle caused by the high level of eosinophils, although some are deaths due to inflammation of the arteries that supply blood to the heart or pericardial tamponade.[12] Kidney complications have been reported as being less common.[13] Complications in the kidneys can include glomerulonephritis, which prevents the kidneys' ability to filter the blood, ultimately causing wastes to build up in the bloodstream.[14]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic markers include eosinophil granulocytes and granulomas in affected tissue, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) against neutrophil granulocytes. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for diagnosis of Churg–Strauss syndrome lists these criteria:

- Asthma

- Eosinophilia, i.e. eosinophil blood count greater than 500/microliter, or hypereosinophilia, i.e. eosinophil blood count greater than 1,500/microliter

- Presence of mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy

- Unfixed pulmonary infiltrates

- Presence of paranasal sinus abnormalities

- Histological evidence of extravascular eosinophils

For classification purposes, a patient shall be said to have EGPA if at least four of these six criteria are positive. The presence of any four or more of the six criteria yields a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 99.7%.[2]

Risk stratification

The French Vasculitis Study Group has developed a five-point system ("five-factor score") that predicts the risk of death in Churg–Strauss syndrome using clinical presentations. These factors are:[15]

- Reduced renal function (creatinine >1.58 mg/dl or 140 μmol/l)

- Proteinuria (>1 g/24h)

- Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, infarction, or pancreatitis

- Involvement of the central nervous system

- Cardiomyopathy

The lack of any of these factors indicates milder case, with a five-year mortality rate of 11.9%. The presence of one factor indicates severe disease, with a five-year mortality rate of 26%, and two or more indicate very severe disease: 46% five-year mortality rate.[16]

Treatment

Treatment for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis includes glucocorticoids (such as prednisolone) and other immunosuppressive drugs (such as azathioprine and cyclophosphamide). In many cases, the disease can be put into a type of chemical remission through drug therapy, but the disease is chronic and lifelong.

A systematic review conducted in 2007 indicated all patients should be treated with high-dose steroids, but in patients with a five-factor score of one or higher, cyclophosphamide pulse therapy should be commenced, with 12 pulses leading to fewer relapses than six. Remission can be maintained with a less toxic drug, such as azathioprine or methotrexate.[17]

On 12 December 2017, the FDA approved mepolizumab, the first drug therapy specifically indicated for the treatment of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis.[18] Patients taking mepolizumab experienced a "significant improvement" in their symptoms.[18] Mepolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets interleukin-5, a major factor in eosinophil survival.[19]

History

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis was first described by pathologists Jacob Churg (1910–2005) and Lotte Strauss (1913–1985) at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City in 1951, using the term "allergic granulomatosis" to describe it.[3][20] They reported "fever...hypereosinophilia, symptoms of cardiac failure, renal damage, and peripheral neuropathy, resulting from vascular embarrassment in various systems of organs"[21] in a series of 13 patients with necrotizing vasculitis previously diagnosed as "periarteritis nodosa", accompanied by hypereosinophilia and severe asthma.[22] Drs. Churg and Strauss noted three features which distinguished their patients from other patients with periarteritis nodosa but without asthma: necrotizing vasculitis, tissue eosinophilia, and extravascular granuloma.[22] As a result, they proposed that these cases were evident of a different disease entity, which they referred to as "allergic granulomatosis and angiitis".[22]

Society and culture

The memoir Patient, by musician Ben Watt, deals with his experience with EGPA in 1992, and his recovery.[23] Watt's case was unusual in that it mainly affected his gastrointestinal tract, leaving his lungs largely unaffected; this unusual presentation contributed to a delay in proper diagnosis. His treatment required the removal of 5 m (15 ft) of necrotized small intestine (about 75%), leaving him on a permanently restricted diet.[23]

Umaru Musa Yar'Adua, the president of Nigeria from 2007 to 2010, reportedly had EGPA and died in office of complications of the disease.[24]

DJ and author Charlie Gillett was diagnosed with EGPA in 2006; he died four years later.[25]

Japanese ski jumper Taku Takeuchi, who won the bronze medal in the team competition, has the disease and competed at the Sochi Olympics less than a month after being released from hospital treatment.[26]

New Zealand reporter and television presenter Toni Street was diagnosed with the condition in 2015.[27][28] Street has had health problems for several years, including removal of her gallbladder four months prior.[29]

Professional basketball player Willie Naulls died on 22 November 2018 in Laguna Niguel, California, from respiratory failure due to EGPA,[30] which he had been battling for eight years.[31]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Churg Strauss Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 11 February 2015. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- 1 2 Masi AT, Hunder GG, Lie JT, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Arend WP, et al. (August 1990). "The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis)". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 33 (8): 1094–100. doi:10.1002/art.1780330806. PMID 2202307.

- 1 2 3 Churg J, Strauss L (March–April 1951). "Allergic granulomatosis, allergic angiitis, and periarteritis nodosa". The American Journal of Pathology. 27 (2): 277–301. PMC 1937314. PMID 14819261.

- ↑ Adu, Emery & Madaio 2012, p. 125.

- 1 2 3 "What Is Churg-Strauss Syndrome?". WebMD. 30 January 2019. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ↑ Montesi SB, Nance JW, Harris RS, Mark EJ (June 2016). "CASE RECORDS of the MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL. Case 17-2016. A 60-Year-Old Woman with Increasing Dyspnea". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (23): 2269–79. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc1516452. PMID 27276565.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Churg-Strauss syndrome - Symptoms". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- 1 2 Della Rossa A, Baldini C, Tavoni A, Tognetti A, Neglia D, Sambuceti G, et al. (November 2002). "Churg-Strauss syndrome: clinical and serological features of 19 patients from a single Italian centre". Rheumatology. 41 (11): 1286–94. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/41.11.1286. PMID 12422002.

- 1 2 3 Churg & Thurlbeck 1995, p. 425.

- ↑ Rich RR, Fleisher, Thomas A., Shearer, William T., Schroeder, Harry, Frew, Anthony J., Weyand, Cornelia M. (2012). Clinical Immunology: Principles and Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 701. ISBN 9780723437109.

- ↑ Nguyen, Yann; Guillevin, Loïc (August 2018). "Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss)". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 39 (4): 471–481. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1669454. ISSN 1069-3424. PMID 30404114. S2CID 53213576.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Churg & Thurlbeck 1995, p. 426.

- ↑ Rich et al. 2012, p. 701.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Guillevin L, Lhote F, Gayraud M, Cohen P, Jarrousse B, Lortholary O, et al. (January 1996). "Prognostic factors in polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome. A prospective study in 342 patients". Medicine. 75 (1): 17–28. doi:10.1097/00005792-199601000-00003. PMID 8569467.

- ↑ Bosch X, Guilabert A, Espinosa G, Mirapeix E (August 2007). "Treatment of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis: a systematic review". JAMA. 298 (6): 655–69. doi:10.1001/jama.298.6.655. PMID 17684188.

- 1 2 "Press Announcements - FDA approves first drug for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis, a rare disease formerly known as the Churg-Strauss Syndrome". www.fda.gov. FDA. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ Giofreddi, Andrea; Maritati, Federica; Oliva, Elena; Buzio, Carlo (3 November 2014). "Eosinophillic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis: An Overview". Front Immunol. 5: 549. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00549. PMC 4217511. PMID 25404930.

- ↑ synd/2733 at Who Named It?

- ↑ Rich et al. 2012, p. 700.

- 1 2 3 Hellmich B, Ehlers S, Csernok E, Gross WL (2003). "Update on the pathogenesis of Churg-Strauss syndrome". Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 21 (6 Suppl 32): S69-77. PMID 14740430. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- 1 2 Whiting S (10 April 1997). "Everything But the Final Song / Ben Watt lives to tell how he almost didn't". SFGate. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks: Yar'Adua Died Of Lung Cancer And Churg Strauss Syndrome, US Cables Confirm". Sahara Reporters. 2 September 2011. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ "Charlie Gillett - Obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 18 March 2010. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ "Japan's Taku Takeuchi overcame illness to win Olympic medal - 'I thought I might even die'". The National. Associated Press. 18 February 2014. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ↑ "New Zealand responds to Toni Street's illness with love and support". Stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ↑ "Toni Street reveals 'dark moments' as she battles deadly disease". NZ Herald. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ↑ "Toni Street's mystery illness revealed". NZ Herald. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ↑ Goldstein R (25 November 2018), "Willie Naulls, Knicks All-Star and Celtics Champion, Dies at 84", The New York Times, archived from the original on 26 November 2018, retrieved 25 May 2021

- ↑ Bolch B (25 November 2018). "Former UCLA great and integration pioneer Willie Naulls dies at 84". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

Further reading

- Adu D, Emery P, Madaio M (2012). Rheumatology and the Kidney (2, illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199579655.

- Churg A, Thurlbeck W (1995). Pathology of the LungM (2, illustrated ed.). Thieme. ISBN 9780865775343.

- Rich RR, Fleisher TA, Shearer WT, Schroeder H, Frew AJ, Weyand CM (2012). Clinical Immunology: Principles and Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780723437109.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |