Diagnosis of malaria

The mainstay of malaria diagnosis has been the microscopic examination of blood, utilizing blood films.[1] Although blood is the sample most frequently used to make a diagnosis, both saliva and urine have been investigated as alternative, less invasive specimens.[2] More recently, modern techniques utilizing antigen tests or polymerase chain reaction have been discovered, though these are not widely implemented in malaria endemic regions.[3][4] Areas that cannot afford laboratory diagnostic tests often use only a history of subjective fever as the indication to treat for malaria.

Blood films

| Species | Appearance | Periodicity | Liver persistent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium vivax |  |

tertian | yes |

| Plasmodium ovale |  |

tertian | no |

| Plasmodium falciparum |  |

tertian | no |

| Plasmodium malariae |  |

quartan | no |

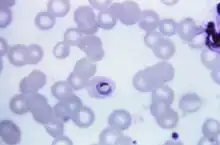

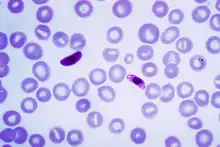

The most economic, preferred, and reliable diagnosis of malaria is microscopic examination of blood films because each of the four major parasite species has distinguishing characteristics. Two sorts of blood film are traditionally used. Thin films are similar to usual blood films and allow species identification because the parasite's appearance is best preserved in this preparation. Thick films allow the microscopist to screen a larger volume of blood and are about eleven times more sensitive than the thin film, so picking up low levels of infection is easier on the thick film, but the appearance of the parasite is much more distorted and therefore distinguishing between the different species can be much more difficult. With the pros and cons of both thick and thin smears taken into consideration, it is imperative to utilize both smears while attempting to make a definitive diagnosis.[5]

From the thick film, an experienced microscopist can detect parasite levels (or parasitemia) as few as 5 parasites/µL blood.[6] Diagnosis of species can be difficult because the early trophozoites ("ring form") of all four species look similar and it is never possible to diagnose species on the basis of a single ring form; species identification is always based on several trophozoites.

As malaria becomes less prevalent due to interventions such as bed nets, the importance of accurate diagnosis increases. This is because the assumption that any patient with a fever has malaria becomes less accurate. As such, significant research is being put into developing low cost microscopy solutions for the Global South.[7]

Plasmodium malariae and P. knowlesi (which is the most common cause of malaria in South-east Asia) look very similar under the microscope. However, P. knowlesi parasitemia increases very fast and causes more severe disease than P. malariae, so it is important to identify and treat infections quickly. Therefore, modern methods such as PCR (see "Molecular methods" below) or monoclonal antibody panels that can distinguish between the two should be used in this part of the world.[8]

Antigen tests

For areas where microscopy is not available, or where laboratory staff are not experienced at malaria diagnosis, there are commercial antigen detection tests that require only a drop of blood.[9] Immunochromatographic tests (also called: Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Tests, Antigen-Capture Assay or "Dipsticks") have been developed, distributed and fieldtested. These tests use finger-stick or venous blood, the completed test takes a total of 15–20 minutes, and the results are read visually as the presence or absence of colored stripes on the dipstick, so they are suitable for use in the field. The threshold of detection by these rapid diagnostic tests is in the range of 100 parasites/µl of blood (commercial kits can range from about 0.002% to 0.1% parasitemia) compared to 5 by thick film microscopy. One disadvantage is that dipstick tests are qualitative but not quantitative – they can determine if parasites are present in the blood, but not how many.

The first rapid diagnostic tests were using Plasmodium glutamate dehydrogenase as antigen.[3] PGluDH was soon replaced by Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase (pLDH). Depending on which monoclonal antibodies are used, this type of assay can distinguish between different species of human malaria parasites, because of antigenic differences between their pLDH isoenzymes. Antibody tests can also be directed against other malarial antigens such as the P. falciparum specific HPR2.

Modern rapid diagnostic tests for malaria often include a combination of two antigens such as a P. falciparum. specific antigen e.g. histidine-rich protein II (HRP II) and either a P. vivax specific antigen e.g. P. vivax LDH or an antigen sensitive to all plasmodium species which affect humans e.g. pLDH. Such tests do not have a sensitivity of 100% and where possible, microscopic examination of blood films should also be performed.

Molecular methods

Molecular methods are available in some clinical laboratories and rapid real-time assays (for example, QT-NASBA based on the polymerase chain reaction)[4] are being developed with the hope of being able to deploy them in endemic areas.

PCR (and other molecular methods) is more accurate than microscopy. However, it is expensive, and requires a specialized laboratory. Moreover, levels of parasitemia are not necessarily correlative with the progression of disease, particularly when the parasite is able to adhere to blood vessel walls. Therefore, more sensitive, low-tech diagnosis tools need to be developed in order to detect low levels of parasitemia in the field.[10]

Another approach is to detect the iron crystal byproduct of hemoglobin that is found in malaria parasites feasting on red blood cells, but not found in normal blood cells. It can be faster, simpler and precise than any other method. Researchers at Rice University have published a preclinical study of their new tech that can detect even a single malaria-infected cell among a million normal cells,.[11][12] They claim it can be operated by nonmedical personal, produce zero false-positive readings, and it doesn't need a needle or any damage done.

Over- and misdiagnosis

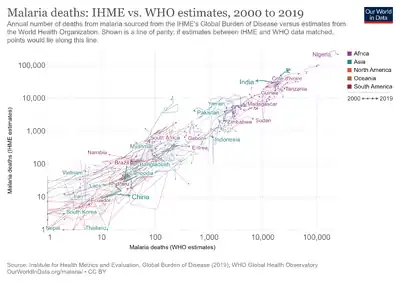

Multiple recent studies have documented malaria overdiagnosis as a persistent issue globally, but especially in African countries.[13][14] Overdiagnosis results in over-inflation of actual malaria rates reported at the local and national levels.[15] Health facilities tend to over-diagnose malaria in patients presenting with symptoms such as fever, due to traditional perceptions such as "any fever being equivalent to malaria"[15] and issues related to laboratory testing (for example high false positivity rates of diagnosis by unqualified personnel [16]). Malaria overdiagnosis leads to under management of other fever-inducing conditions, over-prescription of antimalarial drugs [17][15] and exaggerated perception of high malaria endemicity in regions which are no longer endemic for this infection.[15]

Subjective Diagnosis

Areas that cannot afford laboratory diagnostic tests often use only a history of subjective fever as the indication to treat for malaria. Using Giemsa-stained blood smears from children in Malawi, one study showed that when clinical predictors (rectal temperature, nailbed pallor, and splenomegaly) were used as treatment indications, rather than using only a history of subjective fevers, a correct diagnosis increased from 2% to 41% of cases, and unnecessary treatment for malaria was significantly decreased.[10]

Differential

Fever and septic shock are commonly misdiagnosed as severe malaria in Africa, leading to a failure to treat other life-threatening illnesses. In malaria-endemic areas, parasitemia does not ensure a diagnosis of severe malaria, because parasitemia can be incidental to other concurrent disease. Recent investigations suggest that malarial retinopathy is better (collective sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 90%) than any other clinical or laboratory feature in distinguishing malarial from non-malarial coma.[18]

Quantitative Buffy Coat

Quantitative buffy coat (QBC) is a laboratory test to detect infection with malaria or other blood parasites. The blood is taken in a QBC capillary tube which is coated with acridine orange (a fluorescent dye) and centrifuged; the fluorescing parasites can then be observed under ultraviolet light at the interface between red blood cells and buffy coat. This test is more sensitive than the conventional thick smear, however it is unreliable for the differential diagnosis of species of parasite.[19]

In cases of extremely low white blood cell count, it may be difficult to perform a manual differential of the various types of white cells, and it may be virtually impossible to obtain an automated differential. In such cases the medical technologist may obtain a buffy coat, from which a blood smear is made. This smear contains a much higher number of white blood cells than whole blood.

References

- ↑ Krafts K, Hempelmann E, Oleksyn B (2011). "The color purple: from royalty to laboratory, with apologies to Malachowski". Biotech Histochem. 86 (1): 7–35. doi:10.3109/10520295.2010.515490. PMID 21235291. S2CID 19829220.

- ↑ Sutherland CJ, Hallett R (2009). "Detecting malaria parasites outside the blood". J Infect Dis. 199 (11): 1561–3. doi:10.1086/598857. PMID 19432543.

- 1 2 Ling I.T.; Cooksley S.; Bates P.A.; Hempelmann E.; Wilson R.J.M. (1986). "Antibodies to the glutamate dehydrogenase of Plasmodium falciparum" (PDF). Parasitology. 92 (2): 313–24. doi:10.1017/S0031182000064088. PMID 3086819. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2022-04-22.

- 1 2 Mens PF; Schoone GJ; Kager PA; Schallig HDFH (2006). "Detection and identification of human Plasmodium species with real-time quantitative nucleic acid sequence-based amplification". Malaria Journal. 5 (80): 80. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-5-80. PMC 1592503. PMID 17018138.

- ↑ Warhurst DC, Williams JE (1996). "Laboratory diagnosis of malaria". J Clin Pathol. 49 (7): 533–8. doi:10.1136/jcp.49.7.533. PMC 500564. PMID 8813948.

- ↑ Richard L. Guerrant; David H. Walker; Peter F. Weller (2006). Tropical infectious diseases: principles, pathogens & practice. Elsevier Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-06668-9. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ↑ Bowden AK, Durr NJ, Erickson D, Ozcan A, Ramanujam N, Jacques PV (2020). "Optical Technologies for Improving Healthcare in Low-Resource Settings: introduction to the feature issue". Biomedical Optics Express. 11 (6): 3091–3094. doi:10.1364/BOE.397698. PMC 7316015. PMID 32637243.

- ↑ McCutchan, Thomas F.; Piper, Robert C.; Makler, Michael T. (November 2008). "Use of Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Test to Identify Plasmodium knowlesi Infection". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (11): 1750–2. doi:10.3201/eid1411.080840. PMC 2630758. PMID 18976561.

- ↑ Pattanasin S, Proux S, Chompasuk D, Luwiradaj K, Jacquier P, Looareesuwan S, Nosten F (2003). "Evaluation of a new Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase assay (OptiMAL-IT) for the detection of malaria". Transact Royal Soc Trop Med. 97 (6): 672–4. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(03)80100-1. PMID 16117960.

- 1 2 Redd S, Kazembe P, Luby S, Nwanyanwu O, Hightower A, Ziba C, Wirima J, Chitsulo L, Franco C, Olivar M (2006). "Clinical algorithm for treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children". Lancet. 347 (8996): 223–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90404-3. PMID 8551881. S2CID 10931276. Archived from the original on 2022-07-02. Retrieved 2022-04-22.

- ↑ "Vapor nanobubbles rapidly detect malaria through the skin Archived 2014-01-08 at the Wayback Machine", news.rice.edu

- ↑ "Hemozoin-generated vapor nanobubbles for transdermal reagent- and needle-free detection of malaria", Ekaterina Y. L., et al. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1316253111

- ↑ Ghai, Ria R.; Thurber, Mary I.; El Bakry, Azza; Chapman, Colin A.; Goldberg, Tony L. (2016-09-07). "Multi-method assessment of patients with febrile illness reveals over-diagnosis of malaria in rural Uganda". Malaria Journal. 15 (1): 460. doi:10.1186/s12936-016-1502-4. ISSN 1475-2875. PMC 5015337. PMID 27604542.

- ↑ Reyburn, Hugh; Mbatia, Redepmta; Drakeley, Chris; Carneiro, Ilona; Mwakasungula, Emmanuel; Mwerinde, Ombeni; Saganda, Kapalala; Shao, John; Kitua, Andrew (2004-11-20). "Overdiagnosis of malaria in patients with severe febrile illness in Tanzania: a prospective study". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 329 (7476): 1212. doi:10.1136/bmj.38251.658229.55. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 529364. PMID 15542534.

- 1 2 3 4 Mwanziva, Charles; Shekalaghe, Seif; Ndaro, Arnold; Mengerink, Bianca; Megiroo, Simon; Mosha, Frank; Sauerwein, Robert; Drakeley, Chris; Gosling, Roly (2008-11-05). "Overuse of artemisinin-combination therapy in Mto wa Mbu (river of mosquitoes), an area misinterpreted as high endemic for malaria". Malaria Journal. 7: 232. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-7-232. ISSN 1475-2875. PMC 2588630. PMID 18986520.

- ↑ Yegorov, Sergey; Galiwango, Ronald M.; Ssemaganda, Aloysious; Muwanga, Moses; Wesonga, Irene; Miiro, George; Drajole, David A.; Kain, Kevin C.; Kiwanuka, Noah (2016-11-14). "Low prevalence of laboratory-confirmed malaria in clinically diagnosed adult women from the Wakiso district of Uganda". Malaria Journal. 15 (1): 555. doi:10.1186/s12936-016-1604-z. ISSN 1475-2875. PMC 5109652. PMID 27842555.

- ↑ Salomão, Cristolde A.; Sacarlal, Jahit; Chilundo, Baltazar; Gudo, Eduardo Samo (2015-12-01). "Prescription practices for malaria in Mozambique: poor adherence to the national protocols for malaria treatment in 22 public health facilities". Malaria Journal. 14: 483. doi:10.1186/s12936-015-0996-5. ISSN 1475-2875. PMC 4667420. PMID 26628068.

- ↑ Beare NA, Taylor TE, Harding SP, Lewallen S, Molyneux ME (November 2006). "Malarial retinopathy: a newly established diagnostic sign in severe malaria". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 75 (5): 790–7. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2006.75.790. PMC 2367432. PMID 17123967.

- ↑ Adeoye GO, Nga IC (December 2007). "Comparison of Quantitative Buffy Coat technique (QBC) with Giemsa-stained Thick Film (GTF) for diagnosis of malaria". Parasitol. Int. 56 (4): 308–12. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2007.06.007. PMID 17683979.