Malaria prophylaxis

Malaria prophylaxis is the preventive treatment of malaria. Several malaria vaccines are under development.

For pregnant women who are living in malaria endemic areas, routine malaria chemoprevention is recommended. It improves anemia and parasite level in the blood for the pregnant women and the birthweight in their infants.[1]

Strategies

- Risk management

- Bite prevention—clothes that cover as much skin as possible, insect repellent, insecticide-impregnated bed nets and indoor residual spraying

- Chemoprophylaxis

- Rapid diagnosis and treatment

Recent improvements in malaria prevention strategies have further enhanced its effectiveness in combating areas highly infected with the malaria parasite. Additional bite prevention measures include mosquito and insect repellents that can be directly applied to skin. This form of mosquito repellent is slowly replacing indoor residual spraying, which is considered to have high levels of toxicity by WHO (World Health Organization). Further additions to preventive care are sanctions on blood transfusions. Once the malaria parasite enters the erythrocytic stage, it can adversely affect blood cells, making it possible to contract the parasite through infected blood.

Chloroquine may be used where the parasite is still sensitive, however many malaria parasite strains are now resistant.[2] Mefloquine (Lariam), or doxycycline (available generically), or the combination of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride (Malarone) are frequently recommended.[2]

Medications

In choosing the agent, it is important to weigh the risk of infection against the risks and side effects associated with the medications.[3]

Disruptive prophylaxis

An experimental approach involves preventing the parasite from binding with red blood cells by blocking calcium signalling between the parasite and the host cell. Erythrocyte-binding-like proteins (EBLs) and reticulocyte-binding protein homologues (RHs) are both used by specialized P. falciparum organelles known as rhoptries and micronemes to bind with the host cell. Disrupting the binding process can stop the parasite.[4][5]

Monoclonal antibodies were used to interrupt calcium signalling between PfRH1 (an RH protein), EBL protein EBA175 and the host cell. This disruption completely stopped the binding process.[4]

Suppressive prophylaxis

Chloroquine, proguanil, mefloquine, and doxycycline are suppressive prophylactics. This means that they are only effective at killing the malaria parasite once it has entered the erythrocytic stage (blood stage) of its life cycle, and therefore have no effect until the liver stage is complete. That is why these prophylactics must continue to be taken for four weeks after leaving the area of risk.

Mefloquine, doxycycline, and atovaquone-proguanil appear to be equally effective at reducing the risk of malaria for short-term travelers and are similar with regard to their risk of serious side effects.[2] Mefloquine is sometimes preferred due to its once a week dose, however mefloquine is not always as well tolerated when compared with atovaquone-proguanil.[2] There is low-quality evidence suggesting that mefloquine and doxycycline are similar with regards to the number of people who discontinue treatments due to minor side effects.[2] People who take mefloquine may be more likely to experience minor side effects such as sleep disturbances, depressed mood, and an increase in abnormal dreams.[2] There is very low quality evidence indicating that doxycycline use may be associated with an increased risk of indigestion, photosensitivity, vomiting, and yeast infections, when compared with mefloquine and atovaquone-proguanil.[2]

Causal prophylaxis

Causal prophylactics target not only the blood stages of malaria, but the initial liver stage as well. This means that the user can stop taking the drug seven days after leaving the area of risk. Malarone and primaquine are the only causal prophylactics in current use.

Regimens

Specific regimens are recommended by the WHO,[7] UK HPA[8][9] and CDC[10] for prevention of P. falciparum infection. HPA and WHO advice are broadly in line with each other (although there are some differences). CDC guidance frequently contradicts HPA and WHO guidance.

These regimens include:

- doxycycline 100 mg once daily (started one day before travel, and continued for four weeks after returning);

- mefloquine 250 mg once weekly (started two-and-a-half weeks before travel, and continued for four weeks after returning);

- atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone) 1 tablet daily (started one day before travel, and continued for 1 week after returning). Can also be used for therapy in some cases.

In areas where chloroquine remains effective:

- chloroquine 300 mg once weekly, and proguanil 200 mg once daily (started one week before travel, and continued for four weeks after returning);

- hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once weekly (started one to two weeks before travel and continued for four weeks after returning)

What regimen is appropriate depends on the person who is to take the medication as well as the country or region travelled to. This information is available from the UK HPA, WHO or CDC (links are given below). Doses depend also on what is available (e.g., in the US, mefloquine tablets contain 228 mg base, but 250 mg base in the UK). The data is constantly changing and no general advice is possible.

Doses given are appropriate for adults and children aged 12 and over.

Other chemoprophylactic regimens that have been used on occasion:

- Dapsone 100 mg and pyrimethamine 12.5 mg once weekly (available as a combination tablet called Maloprim or Deltaprim): this combination is not routinely recommended because of the risk of agranulocytosis;

- Primaquine 30 mg once daily (started the day before travel, and continuing for seven days after returning): this regimen is not routinely recommended because of the need for G-6-PD testing prior to starting primaquine (see the article on primaquine for more information).

- Quinine sulfate 300 to 325 mg once daily: this regimen is effective but not routinely used because of the unpleasant side effects of quinine.

Prophylaxis against Plasmodium vivax requires a different approach given the long liver stage of this parasite.[11] This is a highly specialist area.

Vaccines

In November 2012, findings from a Phase III trials of an experimental malaria vaccine known as RTS,S reported that it provided modest protection against both clinical and severe malaria in young infants. The efficacy was about 30% in infants 6 to 12 weeks of age and about 50% in infants 5 to 17 months of age in the first year of the trial.[12]

The RTS,S vaccine was engineered using a fusion hepatitis B surface protein containing epitopes of the outer protein of Plasmodium falciparum malaria sporozite, which is produced in yeast cells. It also contains a chemical adjuvant to boost the immune system response.[13] The vaccine is being developed by PATH and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), which has spent about $300 million on the project, plus about $200 million more from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.[14]

Risk factors

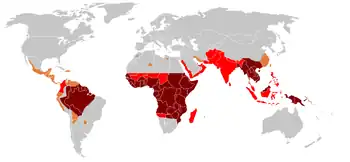

Most adults from endemic areas have a degree of long-term infection, which tends to recur, and also possess partial immunity (resistance); the resistance reduces with time, and such adults may become susceptible to severe malaria if they have spent a significant amount of time in non-endemic areas. They are strongly recommended to take full precautions if they return to an endemic area.

History

Malaria is one of the oldest known pathogens, and began having a major impact on human survival about 10,000 years ago with the birth of agriculture. The development of virulence in the parasite has been demonstrated using genomic mapping of samples from this period, confirming the emergence of genes conferring a reduced risk of developing the malaria infection. References to the disease can be found in manuscripts from ancient Egypt, India and China, illustrating its wide geographical distribution. The first treatment identified is thought to be Quinine, one of four alkaloids from the bark of the Cinchona tree. Originally it was used by the tribes of Ecuador and Peru for treating fevers. Its role in treating malaria was recognised and recorded first by an Augustine monk from Lima, Peru in 1633. Seven years later the drug had reached Europe and was being used widely with the name 'the Jesuit's bark'. From this point onwards the use of Quinine and the public interest in malaria increased, although the compound was not isolated and identified as the active ingredient until 1820. By the mid-1880s the Dutch had grown vast plantations of cinchona trees and monopolised the world market.

Quinine remained the only available treatment for malaria until the early 1920s. During the First World War German scientists developed the first synthetic antimalarial compound—Atabrin and this was followed by Resochin and Sontochin derived from 4-aminoquinoline compounds. American troops, on capturing Tunisia during the Second World War, acquired, then altered the drugs to produce Chloroquine.

The development of new antimalarial drugs spurred the World Health Organization in 1955 to attempt a global malaria eradication program. This was successful in much of Brazil, the US and Egypt but ultimately failed elsewhere. Efforts to control malaria are still continuing, with the development of drug-resistant parasites presenting increasingly difficult problems.

The CDC publishes recommendations for travels advising about the risk of contracting malaria in various countries.[15]

Some of the factors in deciding whether to use chemotherapy as malaria pre-exposure prophylaxis include the specific itinerary, length of trip, cost of drug, previous adverse reactions to antimalarials, drug allergies, and current medical history.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ Radeva-Petrova, D; Kayentao, K; ter Kuile, FO; Sinclair, D; Garner, P (10 October 2014). "Drugs for preventing malaria in pregnant women in endemic areas: any drug regimen versus placebo or no treatment". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD000169. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000169.pub3. PMC 4498495. PMID 25300703.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tickell-Painter M, Maayan N, Saunders R, Pace C, Sinclair D (October 2017). "Mefloquine for preventing malaria during travel to endemic areas". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD006491. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006491.pub4. PMC 5686653. PMID 29083100.

- ↑ McMillan JA, Feigin RD, DeAngelis C, Jones MD (1 April 2006). Oski's pediatrics: principles & practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1348. ISBN 978-0-7817-3894-1. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- 1 2 "Shutting the door on Malaria offers new vaccine hope". 19 December 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ↑ Gao X, Gunalan K, Yap SS, Preiser PR (2013). "Triggers of key calcium signals during erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum". Nature Communications. 4: 2862. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2862G. doi:10.1038/ncomms3862. PMC 3868333. PMID 24280897.

- ↑ "Image Library: Malaria". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 15, 2010. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ The World Health Organization Archived 2007-12-17 at the Wayback Machine provides country-specific advice on malaria prevention.

- ↑ 2007 guidelines are available from the UK Health Protection Agency Archived 2013-09-28 at the Wayback Machine website as a PDF file and includes detailed country-specific information for UK travellers.

- ↑ "Malaria: guidance, data and analysis". Public Health England. June 19, 2013. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- ↑ the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Archived 2018-07-24 at the Wayback Machine website hosts constantly updated country-specific information on malaria. The advice on this website is less detailed, is very cautious and may not be appropriate for all areas within a given country. This is the preferred site for travellers from the US.

- ↑ Schwartz E, Parise M, Kozarsky P, Cetron M (October 2003). "Delayed onset of malaria--implications for chemoprophylaxis in travelers". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (16): 1510–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021592. PMID 14561793.

- ↑ RTS, S Clinical Trials Partnership, Agnandji ST, Lell B, Fernandes JF, Abossolo BP, Methogo BG, et al. (December 2012). "A phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African infants" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (24): 2284–95. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208394. PMID 23136909. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-20. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ↑ Casares S, Brumeanu TD, Richie TL (July 2010). "The RTS,S malaria vaccine". Vaccine. 28 (31): 4880–94. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.033. PMID 20553771. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ↑ Stein R (18 October 2011). "Experimental malaria vaccine protects many children, study shows". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- 1 2 Tan KR, Mali S, Arguin PM (2010). "Malaria Risk Information and Prophylaxis, by Country". Travelers' Health - Yellow Book. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.