Freeman–Sheldon syndrome

| Freeman–Sheldon syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Distal arthrogryposis type 2A (DA2A), craniocarpotarsal dysplasia, craniocarpotarsal dystrophy, cranio-carpo-tarsal syndrome, whistling face–windmill vane hand syndrome | |

| |

Freeman–Sheldon syndrome (FSS) is a very rare form of multiple congenital contracture (MCC) syndromes (arthrogryposes) and is the most severe form of distal arthrogryposis (DA).[1][2][3] It was originally described by Ernest Arthur Freeman and Joseph Harold Sheldon in 1938.[4][5]: 577

As of 2007, only about 100 cases had been reported in medical literature.[6]

Signs and symptoms

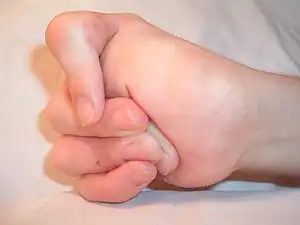

The symptoms of Freeman–Sheldon syndrome include drooping of the upper eyelids, strabismus, low-set ears, a long philtrum, gradual hearing loss, scoliosis and walking difficulties. Gastroesophageal reflux has been noted during infancy, but usually improves with age. The tongue may be small, and the limited movement of the soft palate may cause nasal speech. Often there is an H- or Y-shaped dimpling of the skin over the chin.

Cause

FSS is caused by genetic changes. Krakowiak et al. (1998) mapped the distal arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (DA2B; MIM #601680) gene, a syndrome very similar in phenotypic expression to classic FSS, to 11p15.5-pter.[7][8] Other mutations have been found as well.[9][10] In FSS, inheritance may be either autosomal dominant, most often demonstrated.[11][12][13] or autosomal recessive (MIM 277720).[14][15][16][17] Alves and Azevedo (1977) note most reported cases of DA2A have been identified as new allelic variation.[18] Toydemir et al. (2006) showed that mutations in embryonic myosin heavy chain 3 (MYH3; MIM *160270), at 17p-13.1-pter, caused classic FSS phenotype, in their screening of 28 (21 sporadic and 7 familial) probands with distal arthrogryposis type 2A.[19][20] In 20 patients (12 and 8 probands, respectively), missense mutations (R672H; MIM *160270.0001 and R672C; MIM *160270.0002) caused substitution of arg672, an embryonic myosin residue retained post-embryonically.[19][20][20] Of the remaining 6 patients in whom they found mutations, 3 had missense private de novo (E498G; MIM *160270.0006 and Y583S) or familial mutations (V825D; MIM *160270.0004); 3 other patients with sporadic expression had de novo mutations (T178I; MIM *160270.0003), which was also found in DA2B; 2 patients had no recognized mutations.[19][20]

Diagnosis

Freeman–Sheldon syndrome is a type of distal arthrogryposis, related to distal arthrogryposis type 1 (DA1).[21] In 1996, more strict criteria for the diagnosis of Freeman–Sheldon syndrome were drawn up, assigning Freeman–Sheldon syndrome as distal arthrogryposis type 2A (DA2A).[3]

On the whole, DA1 is the least severe; DA2B is more severe with additional features that respond less favourably to therapy. DA2A (Freeman–Sheldon syndrome) is the most severe of the three, with more abnormalities and greater resistance to therapy.[3]

Freeman–Sheldon syndrome has been described as a type of congenital myopathy.[22]

In March 2006, Stevenson et al. published strict diagnostic criteria for distal arthrogryposis type 2A (DA2A) or Freeman–Sheldon syndrome. These included two or more features of distal arthrogryposis: microstomia, whistling-face, nasolabial creases, and 'H-shaped' chin dimple.[2]

Management

Surgical and anesthetic considerations

Patients must have early consultation with craniofacial and orthopaedic surgeons, when craniofacial,[23][24][25] clubfoot,[26] or hand correction[27][28][29][30] is indicated to improve function or aesthetics. Operative measures should be pursued cautiously, with avoidance of radical measures and careful consideration of the abnormal muscle physiology in Freeman–Sheldon syndrome. Unfortunately, many surgical procedures have suboptimal outcomes, secondary to the myopathy of the syndrome.

When operative measures are to be undertaken, they should be planned for as early in life as is feasible, in consideration of the tendency for fragile health. Early interventions hold the possibility to minimise developmental delays and negate the necessity of relearning basic functions.

Due to the abnormal muscle physiology in Freeman–Sheldon syndrome, therapeutic measures may have unfavourable outcomes.[31] Difficult endotracheal intubations and vein access complicate operative decisions in many DA2A patients, and malignant hyperthermia (MH) may affect individuals with FSS, as well.[32][33][34][35] Cruickshanks et al. (1999) reports uneventful use of non-MH-triggering agents.[36] Reports have been published about spina bifida occulta in anaesthesia management[37] and cervical kyphoscoliosis in intubations.[38]

Medical emphasis

General health maintenance should be the therapeutic emphasis in Freeman–Sheldon syndrome. The focus is on limiting exposure to infectious diseases because the musculoskeletal abnormalities make recovery from routine infections much more difficult in FSS. Pneumonitis and bronchitis often follow seemingly mild upper respiratory tract infections. Though respiratory challenges and complications faced by a patient with FSS can be numerous, the syndrome’s primary involvement is limited to the musculoskeletal systems, and satisfactory quality and length of life can be expected with proper care.

Prognosis

There are little data on prognosis. Rarely, some patients have died in infancy from respiratory failure; otherwise, life expectancy is considered to be normal.

Epidemiology

By 1990, 65 patients had been reported in the literature, with no sex or ethnic preference notable.[39] Some individuals present with minimal malformation; rarely patients have died during infancy as a result of severe central nervous system involvement[40] or respiratory complications.[41] Several syndromes are related to the Freeman–Sheldon syndrome spectrum, but more information is required before undertaking such nosological delineation.[42][43][44]

Research directions

One research priority is to determine the role and nature of malignant hyperthermia in FSS. Such knowledge would benefit possible surgical candidates and the anaesthesiology and surgical teams who would care for them. MH may also be triggered by stress in patients with muscular dystrophies.[45] Much more research is warranted to evaluate this apparent relationship of idiopathic hyperpyrexia, MH, and stress. Further research is wanted to determine epidemiology of psychopathology in FSS and refine therapy protocols.

Eponym

It is named for British orthopaedic surgeon Ernest Arthur Freeman (1900–1975) and British physician Joseph Harold Sheldon (1893–1972), who first described it in 1938.[4][5]: 577

References

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 193700

- 1 2 Stevenson, DA; Carey JC; Palumbos J; Rutherford A; Dolcourt J; Bamshad MJ (March 2006). "Clinical characteristics and natural history of Freeman-Sheldon syndrome". Pediatrics. 117 (3): 754–62. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1219. PMID 16510655. S2CID 7952828. Archived from the original on 2011-05-02. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- 1 2 3 Bamshad M, Jorde LB, Carey JC (November 1996). "A revised and extended classification of the distal arthrogryposes". Am. J. Med. Genet. 65 (4): 277–81. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19961111)65:4<277::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-M. PMID 8923935.

- 1 2 Freeman, EA; Sheldon JH (1938). "Cranio-carpo-tarsal dystrophy: undescribed congenital malformation". Arch Dis Child. 13 (75): 277–83. doi:10.1136/adc.13.75.277. PMC 1975576. PMID 21032118.

- 1 2 James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ "Freeman Sheldon Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2019-09-12.

- ↑ Krakowiak PA, O'Quinn JR, Bohnsack JF, et al. (1997). "A variant of Freeman-Sheldon syndrome maps to 11p15.5-pter". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 60 (2): 426–32. PMC 1712403. PMID 9012416.

- ↑ Krakowiak PA, Bohnsack JF, Carey JC, Bamshad M (1998). "Clinical analysis of a variant of Freeman-Sheldon syndrome (DA2B)". Am. J. Med. Genet. 76 (1): 93–8. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980226)76:1<93::AID-AJMG17>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 9508073.

- ↑ Sung SS, Brassington AM, Krakowiak PA, Carey JC, Jorde LB, Bamshad M (2003). "Mutations in TNNT3 cause multiple congenital contractures: a second locus for distal arthrogryposis type 2B". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73 (1): 212–4. doi:10.1086/376418. PMC 1180583. PMID 12865991.

- ↑ Sung SS, Brassington AM, Grannatt K, et al. (2003). "Mutations in genes encoding fast-twitch contractile proteins cause distal arthrogryposis syndromes". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72 (3): 681–90. doi:10.1086/368294. PMC 1180243. PMID 12592607.

- ↑ Aalam M, Kühhirt M (1972). "[Windmill vane-like finger deformities]". Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb (in Deutsch). 110 (3): 395–8. PMID 4263226.

- ↑ Jorgenson RJ (1974). "M--craniocarpotarsal dystrophy (whistling face syndrome) in two families". Birth Defects Orig. Artic. Ser. 10 (5): 237–42. PMID 4220006.

- ↑ Wettstein A, Buchinger G, Braun A, von Bazan UB (1980). "A family with whistling-face-syndrome". Hum. Genet. 55 (2): 177–89. doi:10.1007/BF00291765. PMID 7450762. S2CID 8059018.

- ↑ Kousseff BG, McConnachie P, Hadro TA (1982). "Autosomal recessive type of whistling face syndrome in twins". Pediatrics. 69 (3): 328–31. PMID 7199706.

- ↑ Kaul KK (1981). "Whistling face syndrome (craniocarpotarsal dysplasia)". Indian Pediatr. 18 (1): 72–3. PMID 7262998.

- ↑ Guzzanti V, Toniolo RM, Lembo A (1990). "[The Freeman-Sheldon syndrome]". Arch Putti Chir Organi Mov (in italiano). 38 (1): 215–22. PMID 2136374.

- ↑ Sánchez JM, Kaminker CP (1986). "New evidence for genetic heterogeneity of the Freeman-Sheldon syndrome". Am. J. Med. Genet. 25 (3): 507–11. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320250312. PMID 3789012.

- ↑ Alves AF, Azevedo ES (1977). "Recessive form of Freeman-Sheldon's syndrome or 'whistling face'". J. Med. Genet. 14 (2): 139–41. doi:10.1136/jmg.14.2.139. PMC 1013533. PMID 856233.

- 1 2 3 Toydemir RM, Rutherford A, Whitby FG, Jorde LB, Carey JC, Bamshad MJ (2006). "Mutations in embryonic myosin heavy chain (MYH3) cause Freeman-Sheldon syndrome and Sheldon-Hall syndrome". Nat. Genet. 38 (5): 561–5. doi:10.1038/ng1775. PMID 16642020. S2CID 8226091.

- 1 2 3 4 Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): MYOSIN, HEAVY CHAIN 3, SKELETAL MUSCLE, EMBRYONIC; MYH3 - 160720

b .0001 c .0002 d .0004 e .0006, .0003 - ↑ Hall JG, Reed SD, Greene G (February 1982). "The distal arthrogryposes: delineation of new entities—review and nosologic discussion". Am. J. Med. Genet. 11 (2): 185–239. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320110208. PMID 7039311.

- ↑ Vanĕk J, Janda J, Amblerová V, Losan F (June 1986). "Freeman-Sheldon syndrome: a disorder of congenital myopathic origin?". J. Med. Genet. 23 (3): 231–6. doi:10.1136/jmg.23.3.231. PMC 1049633. PMID 3723551.

- ↑ Vaitiekaitis AS, Hornstein L, Neale HW (September 1979). "A new surgical procedure for correction of lip deformity in cranio-carpo-tarsal dysplasia (whistling face syndrome)". J Oral Surg. 37 (9): 669–72. PMID 288890.

- ↑ Nara T (July 1981). "Reconstruction of an upper lip and the coloboma in the nasal ala accompanying with Freeman-Sheldon syndrome". Nippon Geka Hokan. 50 (4): 626–32. PMID 7316645.

- ↑ Ferreira LM, Minami E, Andrews Jde M (April 1994). "Freeman-Sheldon syndrome: surgical correction of microstomia". Br J Plast Surg. 47 (3): 201–2. doi:10.1016/0007-1226(94)90056-6. PMID 8193861.

- ↑ Malkawi H, Tarawneh M (July 1983). "The whistling face syndrome, or craniocarpotarsal dysplasia. Report of two cases in a father and son and review of the literature". J Pediatr Orthop. 3 (3): 364–9. doi:10.1097/01241398-198307000-00017. PMID 6874936. S2CID 22025528.

- ↑ Call WH, Strickland JW (March 1981). "Functional hand reconstruction in the whistling-face syndrome". J Hand Surg [Am]. 6 (2): 148–51. doi:10.1016/s0363-5023(81)80168-2. PMID 7229290.

- ↑ Martini AK, Banniza von Bazan U (1983). "[Hand deformities in Freeman-Sheldon syndrome and their surgical treatment]". Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb (in Deutsch). 121 (5): 623–9. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1053288. PMID 6649810.

- ↑ Martini AK, Banniza von Bazan U (December 1982). "[Surgical treatment of the hand deformity in Freeman-Sheldon syndrome]". Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir (in Deutsch). 14 (4): 210–2. PMID 6763591.

- ↑ Wenner SM, Shalvoy RM (November 1989). "Two-stage correction of thumb adduction contracture in Freeman-Sheldon syndrome (craniocarpotarsal dysplasia)". J Hand Surg [Am]. 14 (6): 937–40. doi:10.1016/S0363-5023(89)80040-1. PMID 2584652.

- ↑ Aldinger G, Eulert J (1983). "[The Freeman-Sheldon Syndrome]". Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb (in Deutsch). 121 (5): 630–3. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1053289. PMID 6649811.

- ↑ Laishley RS, Roy WL (1986). "Freeman-Sheldon syndrome: report of three cases and the anaesthetic implications". Can Anaesth Soc J. 33 (3 Pt 1): 388–93. doi:10.1007/BF03010755. PMID 3719442.

- ↑ Munro HM, Butler PJ, Washington EJ (1997). "Freeman-Sheldon (whistling face) syndrome. Anaesthetic and airway management". Paediatr Anaesth. 7 (4): 345–8. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9592.1997.d01-90.x. PMID 9243695. S2CID 40852324.

- ↑ Yamamoto S, Osuga T, Okada M, et al. (1994). "[Anesthetic management of a patient with Freeman-Sheldon syndrome]". Masui (in 日本語). 43 (11): 1748–53. PMID 7861610.

- ↑ Sobrado CG, Ribera M, Martí M, Erdocia J, Rodríguez R (1994). "[Freeman-Sheldon syndrome: generalized muscular rigidity after anesthetic induction]". Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim (in español). 41 (3): 182–4. PMID 8059048.

- ↑ Cruickshanks GF, Brown S, Chitayat D (1999). "Anesthesia for Freeman-Sheldon syndrome using a laryngeal mask airway". Can J Anaesth. 46 (8): 783–7. doi:10.1007/BF03013916. PMID 10451140.

- ↑ Namiki M, Kawamata T, Yamakage M, Matsuno A, Namiki A (2000). "[Anesthetic management of a patient with Freeman-Sheldon syndrome]". Masui (in 日本語). 49 (8): 901–2. PMID 10998888.

- ↑ Vas L, Naregal P (1998). "Anaesthetic management of a patient with Freeman Sheldon syndrome". Paediatr Anaesth. 8 (2): 175–7. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9592.1998.00676.x. PMID 9549749. S2CID 37359095.

- ↑ "Freeman-Sheldon syndrome". Orphanet Encyclopedia. Comier-Daire.

- ↑ Zampino G, Conti G, Balducci F, Moschini M, Macchiaiolo M, Mastroiacovo P (March 1996). "Severe form of Freeman-Sheldon syndrome associated with brain anomalies and hearing loss". Am. J. Med. Genet. 62 (3): 293–6. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960329)62:3<293::AID-AJMG17>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 8882790.

- ↑ Rao SS, Chary R, Karan S (March 1979). "Freeman Sheldon syndrome in a newborn (whistling face)--a case report". Indian Pediatr. 16 (3): 291–2. PMID 110675.

- ↑ Fitzsimmons JS, Zaldua V, Chrispin AR (October 1984). "Genetic heterogeneity in the Freeman-Sheldon syndrome: two adults with probable autosomal recessive inheritance". J. Med. Genet. 21 (5): 364–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.21.5.364. PMC 1049318. PMID 6502650.

- ↑ Träger D (1987). "[Cranio-carpo-tarsal dysplasia syndrome (Freeman-Sheldon syndrome, whistling face syndrome)]". Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb (in Deutsch). 125 (1): 106–7. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1039687. PMID 3577337.

- ↑ Simosa V, Penchaszadeh VB, Bustos T (February 1989). "A new syndrome with distinct facial and auricular malformations and dominant inheritance". Am. J. Med. Genet. 32 (2): 184–6. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320320209. PMID 2929657.

- ↑ Litman RS, Rosenberg H (2005). "Malignant hyperthermia: update on susceptibility testing". JAMA. 293 (23): 2918–24. doi:10.1001/jama.293.23.2918. PMID 15956637.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|