May–Hegglin anomaly

| May–Hegglin anomaly | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Döhle leukocyte inclusions with giant platelets and Macrothrombocytopenia with leukocyte inclusions[1] | |

| |

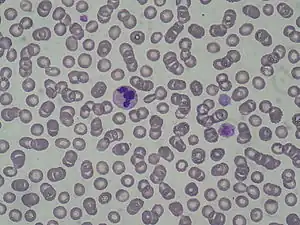

May–Hegglin anomaly (MHA), is a rare genetic disorder of the blood platelets that causes them to be abnormally large.

Signs and symptoms

In the leukocytes, the presence of very small rods (around 3 micrometers), or Döhle-like bodies can be seen in the cytoplasm.

Pathogenesis

MHA is believed to be associated with the MYH9 gene.[2] The pathogenesis of the disorder had been unknown until recently, when autosomal dominant mutations in the gene encoding non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA (MYH9) were identified. Unique cytoplasmic inclusion bodies are aggregates of nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA, and are only present in granulocytes. These May-Hegglin inclusions are large, basophilic, cytoplasmic inclusions resembling Döhle bodies in the granulocytes.[3] It is not yet known why inclusion bodies are not present in platelets, monocytes, and lymphocytes, or how giant platelets are formed. MYH9 is also found to be responsible for several related disorders with macrothrombocytopenia and leukocyte inclusions, including Sebastian, Fechtner, and Epstein syndromes, which feature deafness, nephritis, and/or cataract.[2] MHA is also a feature of the Alport syndrome (hereditary nephritis with sensorineural hearing loss).[4]

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

The DDx of May-Hegglin anomaly is as follows:[5]

- Haemophillia

- Bernard-Soulier syndrome

- Storage pool disease

- Essential Thrombocytopenia

- Von Willebrand Disease

Treatment

May-Hegglin Anomaly can be treated by various methods:

- Medication;Tranexamic Acid

- Desmopressin Acetate

- Platelet Transfusion will not work, because the affected platelets will overtake the new platelets.

History

MHA is named for German physician Richard May (January 7, 1863 – 1936) and Swiss physician Robert Hegglin.[6][7][8] The disorder was first described by Richard May in 1909 and was subsequently described by Robert Hegglin in 1945.

References

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 155100

- 1 2 Saito, H.; Kunishima, S. (Apr 2008). "Historical hematology: May-Hegglin anomaly". American Journal of Hematology. 83 (4): 304–306. doi:10.1002/ajh.21102. ISSN 0361-8609. PMID 17975807. S2CID 34743130.

- ↑ Gülen H, Erbay A, Kazancı E, Vergin C (2006). "A rare familial thrombocytopenia: May-Hegglin anomaly report of two cases and review of the literature". Turk J Haematol. 23 (2): 111–4. PMID 27265293. Archived from the original on 2022-11-12. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Noris P et al. Thrombocytopenia, giant platelets, and leukocyte inclusion bodies (May-Hegglin anomaly): clinical and laboratory findings. Am J Med 1998;104(4):355-60

- ↑ "May Hegglin Anomaly". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ↑ synd/113 at Who Named It?

- ↑ R. May. Leukocyteneinschlüsse. Kasuistische Mitteilung. Deutsches Archiv für klinische Medizin, Leipzig, 1909, 96: 1-6.

- ↑ R. Hegglin. Über eine neue Form einer konstitutionellen Leukozytenanomalie, kombiniert mit Throbopathie. Schweizerische medizinische Wochenschrift, Basel, 1945, 75: 91-92.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |