Glutaraldehyde

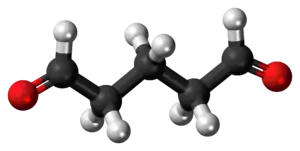

Ball-and-stick model of the glutaraldehyde molecule | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Glutaraldehyde Glutardialdehyde Glutaric acid dialdehyde Glutaric aldehyde Glutaric dialdehyde 1,5-Pentanedial |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | Disinfectant, warts[3][4] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Defined daily dose | Not established[5] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C5H8O2 |

| Molar mass | 100.117 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

Glutaraldehyde, sold under the brandname Cidex and Glutaral among others, is a disinfectant, medication, preservative, and fixative.[3][4][6][7] As a disinfectant, it is used to sterilize surgical instruments and other areas of hospitals.[3] As a medication, it is used to treat warts on the bottom of the feet.[4] Glutaraldehyde is applied as a liquid.[3]

Side effects include skin irritation.[4] If exposed to large amounts, nausea, headache, and shortness of breath may occur.[3] Protective equipment is recommended when used, especially in high concentrations.[3] Glutaraldehyde is effective against a range of microorganisms including spores.[3][8] Glutaraldehyde is a dialdehyde.[9] It works by a number of mechanisms.[8]

Glutaraldehyde came into medical use in the 1960s.[10] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[11] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$1.50–7.40 per liter of 2% solution.[12] There are a number of other commercial uses such as leather tanning.[13]

Uses

Disinfection

Glutaraldehyde is used as a disinfectant and medication.[3][4][14] Usually applied as a solution, it is used to sterilize surgical instruments and other areas.[3]

Fixative

Glutaraldehyde is used in biochemistry applications as an amine-reactive homobifunctional crosslinker and fixative prior to SDS-PAGE, staining. It kills cells quickly by crosslinking their proteins. It is usually employed alone or mixed with formaldehyde[2][15] as the first of two fixative processes to stabilize specimens such as bacteria, plant material, and human cells. A second fixative procedure uses osmium tetroxide to crosslink and stabilize cell and organelle membrane lipids[16]. Fixation is usually followed by dehydration of the tissue in ethanol or acetone, followed by embedding in an epoxy resin or acrylic resin.[17]

Another application for treatment of proteins with glutaraldehyde is the inactivation of bacterial toxins to generate toxoid vaccines, e.g., the pertussis (whooping cough) toxoid component in the Boostrix Tdap vaccine produced by GlaxoSmithKline.[18]In a related application, glutaraldehyde is sometimes employed in the tanning of leather and in embalming.[2]

Wart treatment

As a medication it is used to treat plantar warts.[4] For this purpose, a 10% w/v solution is used. It dries the skin, facilitating physical removal of the wart.[19] Trade names include Glutarol.[20]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is not established[5]

Safety

Side effects include skin irritation.[4] If exposed to large amounts, nausea, headache, and shortness of breath may occur.[3] Protective equipment is recommended when used, especially in high concentrations.[3] Glutaraldehyde is effective against a range of microorganisms including spores.[3][8]

As a strong sterilant, glutaraldehyde is toxic and a strong irritant.[21] There is no strong evidence of carcinogenic activity.[22] Some occupations that work with this chemical have an increased risk of some cancers.[22]

Mechanism of action

A number of mechanisms have been invoked to explain the biocidal properties of glutaraldehyde.[8] Like many other aldehydes, it reacts with amines and thiol groups, which are common functional groups in proteins. Being bi-function, it is also a potential crosslinker.[23]

Production and reactions

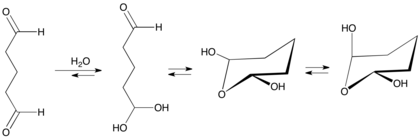

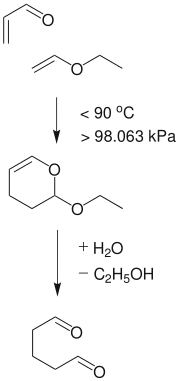

Glutaraldehyde is produced industrially by the oxidation of cyclopentene. Alternatively it can be made by the Diels-Alder reaction of acrolein and vinyl ethers followed by hydrolysis.[24]Glutaraldehyde converts in aqueous solution to various hydrates that in turn convert to other equilibrating species[25]

Monomeric glutaraldehyde polymerizes by aldol condensation reaction yielding alpha, beta-unsaturated poly-glutaraldehyde.[25]

History and culture

Glutaraldehyde came into medical use in the 1960s.[10] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[11] There are a number of other commercial uses such as leather tanning.[13]A glutaraldehyde solution of 2.0% concentration may be used as a biocide for sterilization of surgical equipment[26] It is a sterilant, killing endospores in addition to many microorganisms and viruses.[27] As a biocide, glutaraldehyde is a component of hydraulic fracturing ("fracking") fluid.[28] Bacterial growth impairs extraction from these wells, glutaraldehyde is pumped as a component of the fracturing fluid to inhibit microbial growth.[29]

References

- ↑ Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 907. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- 1 2 3 "Glutaraldehyde". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 323, 325. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 825. ISBN 9780857111562.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ↑ Bonewit-West, Kathy (2015). Clinical Procedures for Medical Assistants. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 96. ISBN 9781455776610. Archived from the original on 2017-09-23. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- ↑ Sullivan, John Burke; Krieger, Gary R. (2001). Clinical Environmental Health and Toxic Exposures. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 601. ISBN 9780683080278. Archived from the original on 2019-02-23. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- 1 2 3 4 Fraise, Adam P.; Maillard, Jean-Yves; Sattar, Syed (2012). Russell, Hugo and Ayliffe's Principles and Practice of Disinfection, Preservation and Sterilization. John Wiley & Sons. p. Chapter 2. ISBN 9781118425862. Archived from the original on 2017-09-23.

- ↑ Pfafflin, James R.; Ziegler, Edward N. (2006). Encyclopedia of Environmental Science and Engineering: A-L. CRC Press. p. 235. ISBN 9780849398438. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- 1 2 Booth, Anne (1998). Sterilization of Medical Devices. CRC Press. p. 8. ISBN 9781574910872. Archived from the original on 2017-09-23.

- 1 2 World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Glutaraldehyde". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 Rietschel, Robert L.; Fowler, Joseph F.; Fisher, Alexander A. (2008). Fisher's Contact Dermatitis. PMPH-USA. p. 359. ISBN 9781550093780. Archived from the original on 2017-09-23.

- ↑ Bonewit-West, Kathy (2015). Clinical Procedures for Medical Assistants. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 96. ISBN 9781455776610. Archived from the original on 2017-09-23.

- ↑ Pal, Kunal; Paulson, Allan T.; Rousseau, Dérick (2013). "14 - Biopolymers in Controlled-Release Delivery Systems". Handbook of Biopolymers and Biodegradable Plastics : Properties, Processing, and Applications. Amsterdam. pp. 329–363. ISBN 978-1-4557-2834-3. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ↑ Layton, Christopher; Bancroft, John D.; Suvarna, S. Kim (2019). "4 - Fixation of tissues". Bancroft's theory and practice of histological techniques (Eighth ed.). [London?]. pp. 40–63. ISBN 978-0-7020-6887-4. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ↑ Watson, Ronald R. (2020). Trace Elements in Laboratory Rodents. CRC Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-000-10864-4. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ↑ Boostrix prescribing information Archived 2011-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, ©2009, GlaxoSmithKline

- ↑ NHS Choices: Glutarol Archived 2015-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Mooney, Jean. Illustrated Dictionary of Podiatry and Foot Science E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-7020-4801-2. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOHS) (a federal government site) > OSH Answers > Diseases, Disorders & Injuries > Asthma Archived 2009-04-27 at the Wayback Machine Document last updated on February 8, 2005

- 1 2 Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Glutaraldehyde Archived 2012-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ H. Uhr; B. Mielke; O. Exner; K. R. Payne; E. Hill (2013). "Biocides". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_563.pub2.

- ↑ Christian Kohlpaintner; Markus Schulte; Jürgen Falbe; Peter Lappe; Jürgen Weber (2008). "Aldehydes, Aliphatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_321.pub2.

- 1 2 Migneault, Isabelle; Dartiguenave, Catherine; Bertrand, Michel J.; Waldron, Karen C. (1 November 2004). "Glutaraldehyde: behavior in aqueous solution, reaction with proteins, and application to enzyme crosslinking". BioTechniques. 37 (5): 790–802. doi:10.2144/04375RV01. ISSN 0736-6205. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ↑ "Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB) : 949". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ↑ Miller, Chris H.; Palenik, Charles John (2014). Infection Control and Management of Hazardous Materials for the Dental Team-E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-323-29140-8. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ↑ Kahrilas, Genevieve A.; Blotevogel, Jens; Corrin, Edward R.; Borch, Thomas (28 September 2016). "Downhole Transformation of the Hydraulic Fracturing Fluid Biocide Glutaraldehyde: Implications for Flowback and Produced Water Quality". Environmental Science & Technology. 50 (20): 11414–11423. doi:10.1021/acs.est.6b02881. ISSN 0013-936X. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ↑ Chen, Jiangang; Al-Wadei, Mohammed H.; Kennedy, Rebekah C. M.; Terry, Paul D. (2014). "Hydraulic Fracturing: Paving the Way for a Sustainable Future?". Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2014. doi:10.1155/2014/656824. ISSN 1687-9805. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- National Pollutant Inventory - Glutaraldehyde Fact Sheet Archived 2013-05-03 at the Wayback Machine

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health - Glutaraldehyde Archived 2011-01-23 at the Wayback Machine

- NIST WebBook Archived 2017-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- "Glutaraldehyde". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-01-02. Retrieved 2020-01-02.