Hyperacusis

| Hyperacusis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hyperacousis |

| |

| An artist's depiction of hyperacusis | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology, otolaryngology |

| Differential diagnosis | Sensory processing disorder, Asperger Syndrome, Autism |

Hyperacusis is the increased sensitivity to sound and a low tolerance for environmental noise.[1] Definitions of hyperacusis can vary significantly;[1] it can refer to normal noises being perceived as: loud, annoying, painful, fear-inducing, or a combination of those.[1][2]

It can be a highly debilitating hearing disorder.[3] Hyperacusis is often coincident with tinnitus.[1] The latter is more common[4] and there are important differences between their involved mechanisms.[3]

Little is known about the prevalence of hyperacusis, in part due to the degree of variation in the term's definition.[1][5] Reported prevalence in children and adolescents ranges from 3% to 17%.[5]

Signs and symptoms

In hyperacusis, the symptoms are ear pain, annoyance, distortions, and general intolerance to many sounds that most people are unaffected by. Crying spells or panic attacks may result from the experience of hyperacusis. It may affect either or both ears.[6] Hyperacusis can also be accompanied by tinnitus. Hyperacusis can result in anxiety, stress and phonophobia. Avoidant behavior is often a response to prevent the effects of hyperacusis and this can include avoiding social situations.

The University of Iowa proposed four sub-categories of the condition:[7]

- pain: sufferers experience discomfort or pain in reaction to certain sounds, usually those that are loud or high in frequency. Pain can be felt in the form of stabbing, burning, coolness, or pain that radiates down the neck.

- loudness: sounds are perceived as louder than their actual decibel level.

- annoyance: certain sounds are irritating.

- fear: sufferers begin avoiding everyday sounds out of fear of triggering symptoms, often isolating themselves at home.

Associated conditions

Some conditions that are associated with hyperacusis[8] include:

Causes

The most common cause of hyperacusis is overexposure to excessively high decibel (sound pressure) levels.[1]

Some sufferers acquire hyperacusis suddenly as a result of taking ear sensitizing drugs, Lyme disease, Ménière's disease, head injury, or surgery. Others are born with sound sensitivity, develop superior canal dehiscence syndrome, have had a history of ear infections, or come from a family that has had hearing problems. Bell's palsy can trigger hyperacusis if the associated flaccid paralysis affects the tensor tympani, and stapedius, two small muscles of the middle ear.[10] Paralysis of the stapedius muscle prevents its function in dampening the oscillations of the ossicles, causing sound to be abnormally loud on the affected side.[18]

Some psychoactive drugs such as LSD, methaqualone, or phencyclidine can cause hyperacusis.[19] An antibiotic, ciprofloxacin, has also been seen to be a cause, known as ciprofloxacin-related hyperacusis.[20] Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome is also a possible cause.[21][22]

Neurophysiological mechanisms

As one important mechanism, adaptation processes in the auditory brain that influence the dynamic range of neural responses are assumed to be distorted by irregular input from the inner ear. This is mainly caused by hearing loss related damage in the inner ear.[23] The mechanism behind hyperacusis is not currently known, but it is suspected to be caused by damage to the inner ear and cochlea. It is theorized that type II afferent fibers become excited after damage to hair cells and synapses, triggering a release of ATP in response.[24] This release of ATP results in pain, sound sensitivity, and cochlear inflammation.

Diagnosis

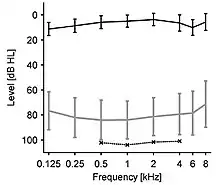

The basic diagnostic test is similar to a normal audiogram. The difference is that additionally to the hearing threshold at each test frequency also the lowest uncomfortable sound level is measured. This level is called loudness discomfort level (LDL), uncomfortable listening level (UCL), or uncomfortable loudness level (ULL). In patients with hyperacusis this level is considerably lower than in normal subjects, and usually across most parts of the auditory spectrum.[1][25]

Treatment

One possible treatment for hyperacusis is retraining therapy which uses broadband noise. Tinnitus retraining therapy, a treatment originally used to treat tinnitus, uses broadband noise to treat hyperacusis. Pink noise can also be used to treat hyperacusis. By listening to broadband noise at soft levels for a disciplined period of time each day, patients can rebuild (i.e., re-establish) their tolerances to sound. Although patients might not always make a complete recovery, the use of broadband noise usually gives some of them a significant improvement in their symptoms, especially if this is combined with counseling.[26][27][2][28]

Another possible treatment is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which may also be combined with retraining therapy.[8][29]

Notable cases

- Musician Jason DiEmilio, who recorded under the name Azusa Plane, had hyperacusis and ultimately went on to commit suicide due in part to his sensitivity to noise. His story was told in BuzzFeed.[30]

- Musician Stephin Merritt has monaural hyperacusis in his left ear, which influences the instrumentation of his band, The Magnetic Fields, leads him to wear earplugs during performances and to cover his affected ear during audience applause.[31]

- Musician Laura Ballance of Superchunk has hyperacusis and no longer tours with the band.[32]

- American politician, activist, and film producer Michael Huffington has mild hyperacusis and underwent sound therapy after finding that running tap water caused ear pain.[33]

- Vladimir Lenin, the Russian communist revolutionary, politician, and political theorist, was reported seriously ill by the latter half of 1921, having hyperacusis and symptoms such as regular headache and insomnia.[34]

- Musician Chris Singleton had hyperacusis, but made a full recovery.[35] His story was told in The Independent.[36]

- Musician Peter Silberman of The Antlers had hyperacusis and tinnitus which put his musical career on hold, but was quoted saying the conditions reduced down to a 'manageable level'[37] He has now resumed his musical career.

- Voice actor Liam O'Brien has hyperacusis, and is quoted as having lost sleep during the time of diagnosis.[38]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tyler RS, Pienkowski M, Roncancio ER, Jun HJ, Brozoski T, Dauman N, et al. (December 2014). "A review of hyperacusis and future directions: part I. Definitions and manifestations". American Journal of Audiology. 23 (4): 402–419. doi:10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0010. PMID 25104073.

- 1 2 Pienkowski M, Tyler RS, Roncancio ER, Jun HJ, Brozoski T, Dauman N, et al. (December 2014). "A review of hyperacusis and future directions: part II. Measurement, mechanisms, and treatment" (PDF). American Journal of Audiology. 23 (4): 420–436. doi:10.1044/2014_AJA-13-0037. PMID 25478787. S2CID 449625. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-09.

- 1 2 Knipper M, Van Dijk P, Nunes I, Rüttiger L, Zimmermann U (December 2013). "Advances in the neurobiology of hearing disorders: recent developments regarding the basis of tinnitus and hyperacusis". Progress in Neurobiology. 111: 17–33. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.08.002. PMID 24012803.

- ↑ "Hyperacusis". British Tinnitus Association. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- 1 2 Rosing SN, Schmidt JH, Wedderkopp N, Baguley DM (June 2016). "Prevalence of tinnitus and hyperacusis in children and adolescents: a systematic review". BMJ Open. 6 (6): e010596. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010596. PMC 4893873. PMID 27259524.

- ↑ "Hyperacusis: An Increased Sensitivity to Everyday Sounds". American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 21 April 2014.

- ↑ "What is Hyperacusis". Hyperacusis Research. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Baguley DM (December 2003). "Hyperacusis". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 96 (12): 582–585. doi:10.1177/014107680309601203. PMC 539655. PMID 14645606.

- ↑ Ralli M, Romani M, Zodda A, Russo FY, Altissimi G, Orlando MP, et al. (April 2020). "Hyperacusis in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Preliminary Study". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (9): 3045. doi:10.3390/ijerph17093045. PMC 7246428. PMID 32349379.

- 1 2 Purves D (2012). Neuroscience (5th ed.). Sunderland, Mass. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

- ↑ Møller A (2011). Textbook of tinnitus. Totowa, N.J. London: Humana Springer distributor. p. 457. ISBN 978-1-60761-145-5.

- ↑ Baguley D (2007). Hyperacusis : mechanisms, diagnosis, and therapies. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing Inc. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-59756-808-1.

- ↑ Granacher R (2008). Traumatic brain injury: methods for clinical and forensic neuropsychiatric assessment. Boca Raton, Fla. London: CRC Taylor & Francis distributor. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8493-8139-3.

- ↑ Montoya-Aranda IM, Peñaloza-López YR, Gutiérrez-Tinajero DJ (2010). "Sjögren's syndrome: Audiological and clinical behaviour in terms of age". Acta Otorrinolaringologica (English Edition). 61 (5): 332–337. doi:10.1016/S2173-5735(10)70061-2. ISSN 2173-5735.

- ↑ Maciaszczyk K, Durko T, Waszczykowska E, Erkiert-Polguj A, Pajor A (February 2011). "Auditory function in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus". Auris, Nasus, Larynx. 38 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2010.04.008. PMID 20576373.

- ↑ Desnick R (2001). Tay–Sachs disease. San Diego, Calif. London: Academic. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-08-049030-4.

- ↑ Zarchi O, Attias J, Gothelf D (2010). "Auditory and visual processing in Williams syndrome". The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences. 47 (2): 125–131. PMID 20733255.

- ↑ Carpenter MB (1985). Core text of neuroanatomy (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-683-01455-6.

- ↑ Barceloux D (2012). Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse : Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 457, 507, and 616. ISBN 978-1-118-10605-1.

- ↑ "Ciprofloxacin Related Hyperacusis". FDA Reports. 2017.

- ↑ Beeley L (June 1991). "Benzodiazepines and tinnitus". BMJ. 302 (6790): 1465. doi:10.1136/bmj.302.6790.1465. PMC 1670117. PMID 2070121.

- ↑ Lader M (June 1994). "Anxiolytic drugs: dependence, addiction and abuse". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 4 (2): 85–91. doi:10.1016/0924-977x(94)90001-9. PMID 7919947. S2CID 44711894.

- ↑ Brotherton H, Plack CJ, Maslin M, Schaette R, Munro KJ (2015). "Pump up the volume: could excessive neural gain explain tinnitus and hyperacusis?". Audiology & Neuro-Otology. 20 (4): 273–282. doi:10.1159/000430459. PMID 26139435. S2CID 32159259.

- ↑ Liu C, Glowatzki E, Fuchs PA (November 2015). "Unmyelinated type II afferent neurons report cochlear damage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (47): 14723–14727. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214723L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1515228112. PMC 4664349. PMID 26553995.

- 1 2 Sheldrake J, Diehl PU, Schaette R (2015). "Audiometric characteristics of hyperacusis patients". Frontiers in Neurology. 6: 105. doi:10.3389/fneur.2015.00105. PMC 4432660. PMID 26029161.

- ↑ Lindsey H (August 2014). "Help for Hyperacusis: Treatments Turn Down Discomfort". The Hearing Journal. 67 (8): 22. doi:10.1097/01.HJ.0000453391.20357.f7. ISSN 0745-7472.

- ↑ Formby C, Hawley ML, Sherlock LP, Gold S, Payne J, Brooks R, et al. (May 2015). "A Sound Therapy-Based Intervention to Expand the Auditory Dynamic Range for Loudness among Persons with Sensorineural Hearing Losses: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial". Seminars in Hearing. 36 (2): 77–110. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1546958. PMC 4906300. PMID 27516711.

- ↑ Fagelson M, Baguley DM (2018). Hyperacusis and Disorders of Sound Intolerance Clinical and Research Perspectives. Plural Publishing. pp. C15, C16. ISBN 978-1-94488-328-7.

- ↑ Aazh H, Moore BC, Lammaing K, Cropley M (September 2016). "Tinnitus and hyperacusis therapy in a UK National Health Service audiology department: Patients' evaluations of the effectiveness of treatments". International Journal of Audiology. 55 (9): 514–522. doi:10.1080/14992027.2016.1178400. PMC 4950421. PMID 27195947.

- ↑ Cohen J (15 March 2013). "When Everyday Sound Becomes Torture". Buzz Feed.

- ↑ Wilson C (2012-03-05). "The return of indie pop's favorite crank". Salon. Retrieved 2021-07-19.

- ↑ Cubarrubia RJ (2013-05-17). "Superchunk Bassist Laura Ballance Won't Tour With Band". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2021-07-19.

- ↑ Huffington M (June 2015). "Rejoining Society". Huff Post.

- ↑ Shub 1966, p. 426; Rice 1990, p. 187; Service 2000, p. 435.

- ↑ "FAQs about Hyperacusis". Chris Singleton. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ↑ "I was allergic to sound". The Independent. 2010-06-01. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ↑ Brodsky R (24 February 2017). "How Peter Silberman Lost His Hearing, Then Rediscovered Sound". pastemagazine.com. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ↑ Foster BW. "'Between the Sheets: Liam O'Brien'". Critical Role. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

Further reading

- Baguley DM, Andersson G (2007). Hyperacusis : mechanisms, diagnosis, and therapies. San Diego: Plural Pub. ISBN 978-1-59756-104-4.

- Jastreboff PJ, Jastreboff MJ (2004). "Decreased Sound Tolerance". In Snow JB (ed.). Tinnitus: theory and management. ISBN 978-1-55009-243-1.