Mastoiditis

| Mastoiditis | |

|---|---|

| |

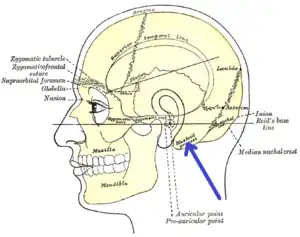

| Side view of head, showing surface relations of bones. (Mastoid process labeled near center.) | |

| Specialty | ENT surgery |

| Symptoms | Redness, swelling, and tenderness behind the ear, fever, ear pain[1] |

| Usual onset | Age less than 2[1] |

| Types | Acute, subacute, incipient[1] |

| Causes | Complication of a middle ear infection[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and examination[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Cellulitis, otitis externa, lymphadenopathy, tumors[1] |

| Prevention | Pneumococcal vaccine[1] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, surgery, steroids[1] |

| Frequency | Uncommon[2] |

Mastoiditis is an infection of the air cells within skull behind the ear.[1] Symptoms may redness, swelling, and tenderness behind the ear together with fever and ear pain.[1][2] Complications may include meningitis, intracranial abscess, and venous sinus thrombosis.[1]

Mastoiditis most commonly occurs as a complication of a middle ear infection.[1] Risk factors include poor immune function.[1] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms and examination.[1] Examination of the ear drum will often show pus.[1] Medical imaging may be useful in cases which are unclear.[1]

Treatment is with antibiotics such as intravenous ceftriaxone or vancomycin.[1] Other measures that may be required include making a cut in the ear drum, tympanostomy tubes, or a mastoidectomy.[1] Other medications that may be used include steroids.[1]

Mastoiditis is uncommon, affected about 2.7 per 100,000 children per year.[2] Children, particularly those less than 2, are more commonly affected than adults.[1] Before the availability of antibiotics and the pneumococcal vaccine the disease was more common.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Some common symptoms and signs of mastoiditis include pain, tenderness, and swelling in the mastoid region. There may be ear pain (otalgia), and the ear or mastoid region may be red (erythematous). Fever or headaches may also be present. Infants usually show nonspecific symptoms, including anorexia, diarrhea, or irritability. Drainage from the ear occurs in more serious cases, often manifest as brown discharge on the pillowcase upon waking.[3][4]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of mastoiditis is straightforward: bacteria spread from the middle ear to the mastoid air cells, where the inflammation causes damage to the bony structures. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis are the most common organisms recovered in acute mastoiditis. Organisms that are rarely found are Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Gram-negative aerobic bacilli, and anaerobic bacteria.[5] P. aeruginosa, Enterobacteriaceae, S. aureus and anaerobic bacteria (Prevotella, Bacteroides, Fusobacterium, and Peptostreptococcus spp. ) are the most common isolates in chronic mastoiditis.[6] Rarely, Mycobacterium species can also cause the infection. Some mastoiditis is caused by cholesteatoma, which is a sac of keratinizing squamous epithelium in the middle ear that usually results from repeated middle-ear infections. If left untreated, the cholesteatoma can erode into the mastoid process, producing mastoiditis, as well as other complications.[3]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of mastoiditis is clinical—based on the medical history and physical examination. Imaging studies provide additional information; The standard method of diagnosis is via MRI scan although a CT scan is a common alternative as it gives a clearer and more useful image to see how close the damage may have gotten to the brain and facial nerves. Planar (2-D) X-rays are not as useful. If there is drainage, it is often sent for culture, although this will often be negative if the patient has begun taking antibiotics. Exploratory surgery is often used as a last resort method of diagnosis to see the mastoid and surrounding areas.[7][8]

.jpg.webp) Acute mastoiditis

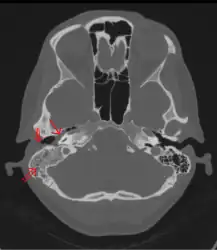

Acute mastoiditis CT scan: Otitis media (simple arrow) and mastoiditis (double arrow) of the right side (left side in image). The external auditory canal is partially occupied by suppuration (triple arrow). 44-year-old woman

CT scan: Otitis media (simple arrow) and mastoiditis (double arrow) of the right side (left side in image). The external auditory canal is partially occupied by suppuration (triple arrow). 44-year-old woman

Treatment

If ear infections are treated in a reasonable amount of time, the antibiotics will usually cure the infection and prevent its spread. For this reason, mastoiditis is rare in developed countries. Most ear infections occur in infants as the eustachian tubes are not fully developed and don't drain readily.

In all developed countries with up-to-date modern healthcare the primary treatment for mastoiditis is administration of intravenous antibiotics. Initially, broad-spectrum antibiotics are given, such as ceftriaxone. As culture results become available, treatment can be switched to more specific antibiotics directed at the eradication of the recovered aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.[6] Long-term antibiotics may be necessary to completely eradicate the infection.[3] If the condition does not quickly improve with antibiotics, surgical procedures may be performed (while continuing the medication). The most common procedure is a myringotomy, a small incision in the tympanic membrane (eardrum), or the insertion of a tympanostomy tube into the eardrum.[8] These serve to drain the pus from the middle ear, helping to treat the infection. The tube is extruded spontaneously after a few weeks to months, and the incision heals naturally. If there are complications, or the mastoiditis does not respond to the above treatments, it may be necessary to perform a mastoidectomy: a procedure in which a portion of the bone is removed and the infection drained.[3]

Prognosis

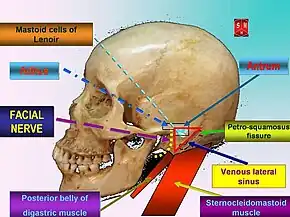

With prompt treatment, it is possible to cure mastoiditis. Seeking medical care early is important. However, it is difficult for antibiotics to penetrate to the interior of the mastoid process and so it may not be easy to cure the infection; it also may recur. Mastoiditis has many possible complications, all connected to the infection spreading to surrounding structures. Hearing loss is likely, or inflammation of the labyrinth of the inner ear (labyrinthitis) may occur, producing vertigo and an ear ringing may develop along with the hearing loss, making it more difficult to communicate. The infection may also spread to the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), causing facial-nerve palsy, producing weakness or paralysis of some muscles of facial expression, on the same side of the face. Other complications include Bezold's abscess, an abscess (a collection of pus surrounded by inflamed tissue) behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the neck, or a subperiosteal abscess, between the periosteum and mastoid bone (resulting in the typical appearance of a protruding ear). Serious complications result if the infection spreads to the brain. These include meningitis (inflammation of the protective membranes surrounding the brain), epidural abscess (abscess between the skull and outer membrane of the brain), dural venous thrombophlebitis (inflammation of the venous structures of the brain), or brain abscess.[7][3]

Epidemiology

In the United States and other developed countries, the incidence of mastoiditis is quite low, around 0.004%, although it is higher in developing countries. The condition most commonly affects children aged from two to thirteen months, when ear infections most commonly occur. Males and females are equally affected.[9]

Society and culture

- the case of Simon Guggenheim's son

- Pete Browning

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Sahi, D; Nguyen, H; Callender, KD (January 2020). "Mastoiditis". PMID 32809712.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 Kynion, R (May 2018). "Mastoiditis". Pediatrics in review. 39 (5): 267–269. doi:10.1542/pir.2017-0128. PMID 29716974.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Young, Tesfa. "Mastoiditis". eMedicine. Archived from the original on July 2, 1998. Retrieved June 10, 2005.

- ↑ "What to Do About Ear infections". webmd.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ Nussinovitch M, Yoeli R, Elishkevitz K, Varsano I (2004). "Acute mastoiditis in children: epidemiologic, clinical, microbiologic, and therapeutic aspects over past years". Clin Pediatr (Phila). 43 (3): 261–7. doi:10.1177/000992280404300307. PMID 15094950.

- 1 2 Brook I (2005). "The role of anaerobic bacteria in acute and chronic mastoiditis". Anaerobe. 11 (5): 252–7. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2005.03.005. PMID 16701580.

- 1 2 "Mastoiditis". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on August 6, 2003. Retrieved July 30, 2003.

- 1 2 Bakhos D, Trijolet JP, Morinière S, Pondaven S, Al Zahrani M, Lescanne E (April 2011). "Conservative management of acute mastoiditis in children". Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 137 (4): 346–50. doi:10.1001/archoto.2011.29. PMID 21502472.

- ↑ "Ear Infections – Treatment". webmd.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Mastoiditis E Medicine Archived 2010-12-04 at the Wayback Machine