Latent tuberculosis

| Latent tuberculosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Latent tuberculosis infection | |

| |

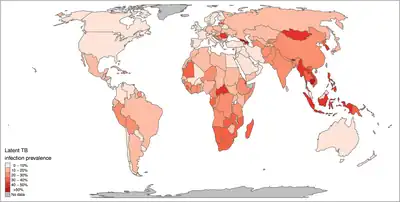

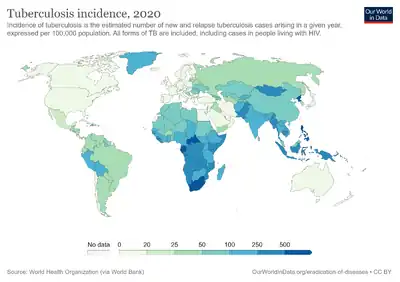

| Global map of prevalence of latent TB infection[1] | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Asymptomatic[2] |

| Causes | M. tuberculosis[2] |

| Risk factors | Weakened immune system, malnutrition[3][4] |

| Diagnostic method | TST and IGRA[2] |

| Treatment | Daily self-administered isoniazid (INH9)[2][5] |

| Frequency | 13 million (U.S.)[6] |

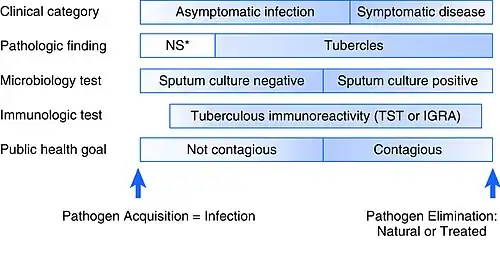

Latent tuberculosis (LTB), also called inactive tuberculosis[7] is when a person infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, does not have symptoms (active tuberculosis). Active tuberculosis can be contagious while latent tuberculosis is not, and it is therefore not possible to get TB from someone with latent tuberculosis. The main risk is that approximately 10% of these people (5% in the first two years after infection and 0.1% per year thereafter) will go on to develop active tuberculosis. This is particularly true, and there is added risk, in particular situations such as medication that suppresses the immune system or advancing age.[8][9]

The identification and treatment of latent TB is an important part of controlling this disease. Various treatment regimens are in use for latent tuberculosis. They generally need to be taken for several months.[7][9]

Signs and symptoms

There are no symptoms in latent Tb.[10]

Transmission

Latent disease

TB bacteria are spread only from a person with active TB disease, in people who develop active TB of the lungs, also called pulmonary TB, the TB skin test will often be positive. In addition, they will show all the signs and symptoms of TB disease, and can pass the bacteria to others. So, if a person with TB of the lungs sneezes, coughs, talks, sings, or does anything that forces the bacteria into the air, other people nearby may breathe in TB bacteria. Statistics show that approximately one-third of people exposed to pulmonary TB become infected with the bacteria, but only one in ten of these infected people develop active TB disease during their lifetimes.However, exposure to tuberculosis is very unlikely to happen when one is exposed for a few minutes in a store or in a few minutes social contact. "It usually takes prolonged exposure to someone with active TB disease for someone to become infected.[11][12]

After exposure, it usually takes 8 to 10 weeks before the TB test would show if someone had become infected."[13]Depending on ventilation and other factors, these tiny droplets [from the person who has active tuberculosis] can remain suspended in the air for several hours. Should another person inhale them, he or she may become infected with TB. The probability of transmission will be related to the infectiousness of the person with TB, the environment where the exposure occurred, the duration of the exposure, and the susceptibility of the host.[14]In fact, "it isn't easy to catch TB. You need consistent exposure to the contagious person for a long time. For that reason, you're more likely to catch TB from a relative than a stranger."[15]

In some countries like Canada people have medical privacy and do not have to reveal their active tuberculosis case to family, friends, or co-workers; therefore, the person who gets latent tuberculosis may never know who had the active case of tuberculosis that caused the latent tuberculosis diagnosis for them. Only by required testing, required in some jobs or developing symptoms of active tuberculosis and visiting a medical doctor who does testing will a person know they have been exposed.[16][17]

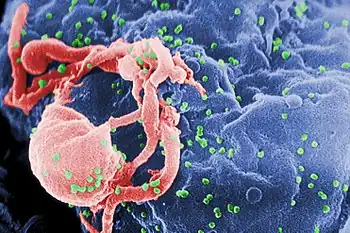

Persons with diabetes may have an 18% chance of converting to active tuberculosis.[18] In fact, death from tuberculosis was greater in diabetic patients.[18] Persons with HIV and latent tuberculosis have a 10% chance of developing active tuberculosis every year. "HIV infection is the greatest known risk factor for the progression of latent M. tuberculosis infection to active TB. In many African countries, 30–60% of all new TB cases occur in people with HIV, and TB is the leading cause of death globally for HIV-infected people."[19]

Reactivation

Once a person has been diagnosed with Latent Tuberculosis (LTBI) and a physician confirms no active tuberculosis, the person should remain alert to symptoms of active tuberculosis for the remainder of their life. Even after completing the full course of medication, there is no guarantee that the tuberculosis bacteria have all been killed."When a person develops active TB (disease), the symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats, weight loss etc.) may be mild for many months; this can lead to delays in seeking care, and results in transmission of the bacteria to others."[21][22][23]

Tuberculosis does not always settle in the lungs. If the outbreak of tuberculosis is in the brain, organs, kidneys, joints, or others areas, the patient may have active tuberculosis for an extended period of time before discovering that they are active. "A person with TB disease may feel perfectly healthy or may only have a cough from time to time." However, these symptoms do not guarantee tuberculosis, and they may not exist at all, yet the patient may still have active tuberculosis. A person with symptoms listed may have active tuberculosis, and the person should immediately see a physician so that tuberculosis is not spread. If a person with the above symptoms does not see a physician, ignoring the symptoms can result in lung damage, eye damage, organ damage and eventually death.[22][24]

When tuberculosis settles in other organs (rather than lungs) or other parts of the body (such as the skeletal), symptoms may be different from when it settles in the lungs. Thus, without the cough or flu-like symptoms, a person can unwittingly have active tuberculosis. Other symptoms include back pain, flank pain, PID symptoms, confusion, coma, difficulty swallowing, and many other symptoms that would be a part of other diseases.[25]

Risk factors

Situations in which tuberculosis may become reactivated are:

- If there is onset of a disease affecting the immune system (such as AIDS) or a disease whose treatment affects the immune system (such as chemotherapy in cancer or systemic steroids in asthma )[3][26]

- Malnutrition (which may be the result of illness or of a prolonged period of not eating, or disturbance in food availability such as famine, residence in refugee camp )[4]

- Degradation of the immune system due to aging.[27]

- Certain systemic diseases such as diabetes,[28] and *Other conditions: debilitating disease (especially haematological and some solid cancers), long-term steroids, end-stage renal disease, silicosis and gastrectomy/jejuno-ileal bypass all confer an increased risk.[29]

- Elderly patients: latent TB may reactivate in elderly patients[30]

- Young age.[31]

Specific situations

Populations at increased risk of progressing to active infection once exposed:[32][33][34]

- Persons with recent TB infection [those infected within the previous two years]

- Illicit intravenous drug users; alcohol and other chronic substance users

Diagnosis

According to the U.S. guidelines, there are multiple size thresholds for declaring a positive result of latent tuberculosis from the Mantoux test: For testees from high-risk groups, such as those who are HIV positive, the cutoff is 5mm of induration; for medium risk groups, 10mm; for low-risk groups, 15mm. The U.S. guidelines recommend that a history of previous BCG vaccination should be ignored. The UK guidelines use to be formulated according to the Heaf test; the Heaf test was discontinued in the UK in 2005. Today, Interferon-gamma release assay or Mantoux test are done. Given that the US recommendation is that prior BCG vaccination be ignored in the interpretation of tuberculin skin tests, false positives with the Mantoux test are possible as a result of: (1) having previously had a BCG, or (2) periodical testing with tuberculin skin tests. Having regular TSTs boosts the immunological response in those people who have previously had BCG, so these people will falsely appear to be tuberculin conversions. However, as Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine is not 100% effective, and is less protective in adults than pediatric patients, not treating these patients could lead to a possible infection. The current US policy seems to reflect a desire to err on the side of safety.The U.S. guidelines also allow for tuberculin skin testing in immunosuppressed patients , whereas the UK guidelines recommend that tuberculin skin tests should not be used for such patients because it is unreliable.[36][37][38][39].

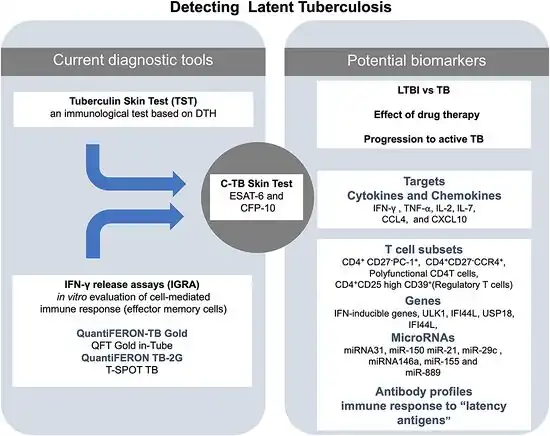

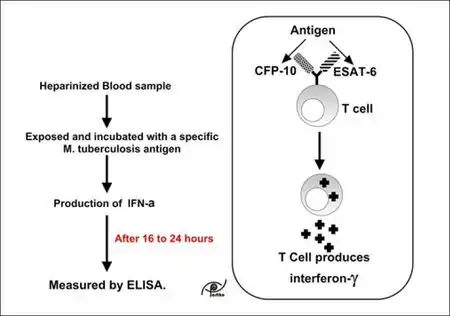

There are two classes of tests commonly used to identify patients with latent tuberculosis: tuberculin skin tests and IFN-γ (Interferon-gamma) tests.[35]

The skin tests currently include the following:[40][41]

- Mantoux test

- Heaf test (discontinued)

IFN-γ tests include the following three:[42]

Tuberculin skin testing

The tuberculin skin test in its first iteration, the Mantoux Test, was developed in 1908. Tuberculin is a standardised dead extract of cultured TB, injected into the skin to measure the person's immune response to the bacteria. So, if a person has been exposed to the bacteria previously, they should express an immune reaction to the injection, usually a mild swelling or redness around the site. There have been two primary methods of TST: the Mantoux test, and the Heaf test. The Heaf test was discontinued in 2005 because the manufacturer deemed its production to be financially unsustainable, though it was previously preferred in the UK because it was felt to require less training to administer and involved less inter-observer variation in its interpretation than the Mantoux test. The Mantoux test was the preferred test in the US, and is now the most widely used TST globally.[35][43][41]

Mantoux test

- See: Mantoux test

The Mantoux test is now standardised by the WHO. 0.1 ml of tuberculin (100 units/ml), which delivers a dose of 5 units is given by intradermal injection into the surface of the lower forearm (subcutaneous injection results in false negatives). A waterproof ink mark is drawn around the injection site so as to avoid difficulty finding it later if the level of reaction is small. The test is read 48 to 72 hours later.[44] The area of induration (NOT of erythema) is measured transversely across the forearm and recorded to the nearest millimetre.[45]

Heaf test

- See:Heaf test

The Heaf test was first described in 1951.[46] The test uses a Heaf gun with disposable single-use heads; each head has six needles arranged in a circle. There are standard heads and pediatric heads: the standard head is used on all patients aged 2 years and older; the pediatric head is for infants under the age of 2. For the standard head, the needles protrude 2 mm when the gun is actuated; for the pediatric heads, the needles protrude 1 mm. Skin is cleaned with alcohol, then tuberculin is evenly smeared on the skin ; the gun is then applied to the skin and fired. The excess solution is then wiped off and a waterproof ink mark is drawn around the injection site. The test is read 2 to 7 days later.[47][40] The scale is:[48]The Heaf test was discontinued in the UK in 2005.[41]

Interferon-γ testing

The role of IFN-γ tests is undergoing constant review and various guidelines have been published with the option for revision as new data becomes available[49]

There are currently two commercially available interferon-γ release assays (IGRAs): QuantiFERON-TB Gold and T-SPOT.TB. These tests are not look for the body's response to specific TB antigens not present in other forms of mycobacteria and BCG (ESAT-6). Whilst these tests are new they are now becoming available globally.[50][51]

CDC:[49]

CDC recommends that QFT-G may be used in all circumstances in which the TST is currently used, including contact investigations, evaluation of recent immigrants, and sequential-testing surveillance programs for infection control (e.g., those for health-care workers).

HPA Interim Guidance:[52]

The HPA recommends the use of IGRA testing in health care workers, if available, in view of the importance of detecting latently infected staff who may go on to develop active disease and come into contact with immunocompromised patients and the logistical simplicity of IGRA testing.

Tuberculin conversion

Tuberculin conversion is said to occur if a patient who has previously had a negative tuberculin skin test develops a positive tuberculin skin test at a later test. It indicates a change from negative to positive, and usually signifies a new infection.[53][54]

Boosting

The phenomenon of boosting is one way of obtaining a false positive test result. Theoretically, a person's ability to develop a reaction to the TST may decrease over time – for example, a person is infected with latent TB as a child, and is administered a TST as an adult. Because there has been such a long time since the immune responses to TB has been necessary, that person might give a negative test result. If so, there is a fairly reasonable chance that the TST triggers a hypersensitivity in the person's immune system – in other words, the TST reminds the person's immune system about TB, and the body overreacts to what it perceives as a reinfection. In this case, when that subject is given the test again they may have a significantly greater reaction to the test, giving a very strong positive; this can be commonly misdiagnosed as Tuberculin Conversion. This can also be triggered by receiving the BCG vaccine, as opposed to a proper infection. Although boosting can occur in any age group, the likelihood of the reaction increases with age.[55]

Boosting is only likely to be relevant if an individual is beginning to undergo periodic TSTs. In this case the standard procedure is called two-step testing. The individual is given their first test and in the event of a negative, given a second test in 1 to 3 weeks. This is done to combat boosting in situations where, had that person waited up to a year to get their next TST, they might still have a boosted reaction, and be misdiagnosed as a new infection.In the US testers are told to ignore the possibility of false positive due to the BCG vaccine, as the BCG is seen as having waning efficacy over time. Therefore, the CDC urges that individuals be treated based on risk stratification regardless of BCG vaccination history, and if an individual receives a negative and then a positive TST they will be assessed for full TB treatment beginning with X-ray to confirm TB is not active and proceeding from there. In the case of BCG vaccinations confusing the results, Interferon-γ tests may be used as they will not be affected by the BCG.[43][56][57] [58]

Classification (Drug-resistant strains)

It is usually assumed by most medical practitioners in the early stages of a diagnosis that a case of latent tuberculosis is the normal or regular strain of tuberculosis. It will therefore be most commonly treated with Isoniazid (the most used treatment for latent tuberculosis.) Only if the tuberculosis bacteria does not respond to the treatment will the medical practitioner begin to consider more virulent strains, requiring significantly longer and more thorough treatment regimens.[59]There are 4 types of tuberculosis recognized in the world today:

- Tuberculosis (TB)[11]

- Multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB)[60]

- Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR TB)[61]

- Totally drug-resistant tuberculosis (TDR TB)[62]

Treatment

The treatment of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) is essential to controlling and eliminating TB by reducing the risk that TB infection will progress to disease. Latent tuberculosis will convert to active tuberculosis in 10% of cases (or more in cases of immune compromised patients). Taking medication for latent tuberculosis is recommended by many doctors.[63][35]

Treatment regimens

It is essential that assessment to rule out active TB be carried out before treatment for LTBI is started. To give treatment for latent tuberculosis to someone with active tuberculosis is a serious error: the tuberculosis will not be adequately treated and there is a serious risk of developing drug-resistant strains of TB.[64][63][65]

There are several treatment regimens currently in use:

- 9H — isoniazid for 9 months is the gold standard (93% effective, in patients with positive test results and fibrotic pulmonary lesions compatible with tuberculosis[66]).

- 6H — Isoniazid for 6 months for in countries with high (or low) TB incidence.[65]

- 4R — rifampicin for 4 months is an alternative [65]

- 3HR — Isoniazid and rifampin may be given daily for three months.[5]

- 2RZ — The two-month regimen of rifampin and pyrazinamide is no longer recommended for treatment of LTBI because of the greatly increased risk of drug-induced hepatitis and death.[67]

- 3HP – three-month (12-dose) regimen of weekly rifapentine and isoniazid.[68][69] The 3HP regimen has to be administered under DOT. A self-administered therapy (SAT) of 3HP is investigated in a large international study.[70]

Efficacy

There is no guaranteed "cure" for latent tuberculosis. "People infected with TB bacteria have a lifetime risk of falling ill with TB..."[21] with those who have compromised immune systems, those with diabetes and those who use tobacco at greater risk.[21]

A person who has taken the complete course of Isoniazid (or other full course prescription for tuberculosis) on a regular, timely schedule may have been cured. "Current standard therapy is isoniazid (INH) which reduce the risk of active TB by as much as 90 per cent (in patients with positive LTBI test results and fibrotic pulmonary lesions compatible with tuberculosis[66]) if taken daily for 9 months."[71] However, if a person has not completed the medication exactly as prescribed, the "cure" is less likely, and the "cure" rate is directly proportional to following the prescribed treatment specifically as recommended. Furthermore, "[I]f you don't take the medicine correctly and you become sick with TB a second time, the TB may be harder to treat if it has become drug resistant."[24] If a patient were to be cured in the strictest definition of the word, it would mean that every single bacterium in the system is removed or dead, and that person cannot get tuberculosis (unless re-infected). However, there is no test to assure that every single bacterium has been killed in a patient's system. As such, a person diagnosed with latent TB can safely assume that, even after treatment, they will carry the bacteria – likely for the rest of their lives. Furthermore, "It has been estimated that up to one-third of the world's population is infected with M. tuberculosis, and this population is an important reservoir for disease reactivation." This means that in areas where TB is endemic treatment may be even less certain to "cure" TB, as reinfection could trigger activation of latent TB already present even in cases where treatment was followed completely.[22]

A 2000 Cochrane review examined six and 12 month courses of isoniazid (INH) for treatment of latent tuberculosis. HIV positive and patients currently or previously treated for tuberculosis were excluded. The main result was a relative risk (RR) of 0.40 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.31 to 0.52) for development of active tuberculosis over two years or longer for patients treated with INH, with no significant difference between treatment courses of six or 12 months (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.73 for six months, and 0.38, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.50 for 12 months).[71]

A Cochrane review in 2013 evaluated four different alternatives regimens to INH monotherapy for preventing active TB in HIV-negative people with latent tuberculosis infection. The evidence from this review found no difference between shorter regimens of Rifampicin or weekly, directly observed Rifapentine plus INH compare to INH monotherapy in preventing active TB in HIV-negative people at risk of developing it . However the review found that the shorter Rifampicin regimen for four months and weekly directly observed Rifapentine plus INH for three months "may have additional advantages of higher treatment completion and improved safety." However the overall quality of evidence was low to moderate (as per GRADE criteria )and none of the included trials were conducted in LMIC nations with high TB transmission and hence might not be applicable to nations with high TB transmission.[22]

Epidemiology

Tuberculosis exists in all countries in the world, though some countries have a larger number of people infected than others. Per 100,000 people, Eswatini has the greatest number of tuberculosis cases in the world (627). Second is Cambodia (560), followed by Zambia (445), fourth is Djibouti (382), fifth is Indonesia (321), Mali (295), Zimbabwe (291), Kenya (291), Papua New Guinea (283) and Gambia (283).[72]

The United States, Sweden and Iceland have some of the lowest rates of tuberculosis at 2 per 100,000.[72] Canada, Netherlands, Jamaica, Norway, Malta, Grenada and Antigua and Barbuda also have low infection rates, at 3 per 100,000. In North America, countries over 10:100,000 include Mexico (14), Belize (18), Bahamas (19), Panama (28), El Salvador (36), Nicaragua (35), Honduras (46), Guatemala (48), and the Dominican Republic (88).[72]

Most Western European countries have less than 10 per 100,000 except Spain (14), Portugal (16), Estonia (27), Latvia (43) and Lithuania (48), while Eastern and Southern European countries tend to have a greater number, with Romania (94) being the highest.[72]

In South America, the countries with the greatest rates of tuberculosis per 100,000 are Bolivia (30) and Guyana (18), with the remaining countries having less than 10:100,000.[73]

"One-third of the world's burden of tuberculosis (TB), or about 4.9 million prevalent cases, is found in the World Health Organization (WHO) South-East Asia Region."[74]

"About one-third of the world's population has latent TB, which means people have been infected by TB bacteria but are not (yet) ill with disease and cannot transmit the disease,"[21] and most of those cases are in developing countries.[19]

"In the US, over half of all active TB cases occur in immigrants. The reported cases of active TB in foreign-born persons has remained at 7000–8000 per year, while the number of cases in US-born people has dropped from 17,000 in 1993 to 6,500 in 2005. As a result, the percentage of active TB cases in immigrants has increased steadily (from 29% of all cases in 1993 to 54% in 2005),"[21] and most of those cases are in developing countries.[19]

Terminology

There is no agreement regarding terminology: the terms preventive therapy and chemoprophylaxis have been used for decades, and are preferred in the UK because it involves giving medication to people who have no disease and are currently well: the reason for giving medication is primarily to prevent people from becoming unwell. In the U.S., physicians talk about latent tuberculosis treatment because the medication does not actually prevent infection: the person is already infected and the medication is intended to prevent existing silent infection from becoming active disease. There are no convincing reasons to prefer one term over the other.[75][76][5]

Controversy

There is controversy over whether people who test positive long after infection have a significant risk of developing the disease (without re-infection). Some researchers and public health officials have warned that this test-positive population is a "source of future TB cases" even in the US and other wealthy countries, and that this "ticking time bomb" should be a focus of attention and resources.[77]

On the other hand, Marcel Behr, Paul Edelstein, and Lalita Ramakrishnan reviewed studies concerning the concept of latent tuberculosis in order to determine whether tuberculosis-infected persons have life-long infection capable of causing disease at any future time. These studies, both published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in 2018 and 2019, show that the incubation period of tuberculosis is short, usually within months after infection, and very rarely more than two years after infection.[78] They also show that more than 90% of people infected with M. tuberculosis for more than two years never develop tuberculosis even if their immune system is severely suppressed.[79] Immunologic tests for tuberculosis infection such as the tuberculin skin test and interferon gamma release assays (IGRA) only indicate past infection, with the majority of previously infected persons no longer capable of developing tuberculosis. Ramakrishnan told the New York Times that researchers "have spent hundreds of millions of dollars chasing after latency, but the whole idea that a quarter of the world is infected with TB is based on a fundamental misunderstanding."[80] The first BMJ article about latency was accompanied by an editorial written by Dr. Soumya Swaminathan, Deputy Director-General of the World Health Organization, who endorsed the findings and called for more funding of TB research directed at the most heavily afflicted parts of the world, rather than disproportionate attention to a relatively minor problem that affects just the wealthy countries.[80]

The World Health Organization no longer endorses the concept that all those with immunologic evidence of past TB infection are currently infected and so are at risk of developing TB some time in the future. In 2022, the WHO issued corrigenda to its 2021 Global TB Report to clarify estimates on the worldwide burden of infected people. These corrigenda deleted "About a quarter of the world's population is infected with M. tuberculosis" and replaced it with "About a quarter of the world's population has been infected with M. tuberculosis." [81][82]

See also

References

- ↑ Houben, Rein M. G. J.; Dodd, Peter J. (October 2016). "The Global Burden of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: A Re-estimation Using Mathematical Modelling". PLOS Medicine. 13 (10): e1002152. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 5079585. PMID 27780211.

- 1 2 3 4 Kiazyk, S.; Ball, T. B. (3 March 2017). "Tuberculosis (TB): Latent tuberculosis infection: An overview". Canada Communicable Disease Report. 43 (3–4): 62–66. doi:10.14745/ccdr.v43i34a01. PMC 5764738. PMID 29770066.

- 1 2 Qiu, Beibei; Wu, Zhuchao; Tao, Bilin; Li, Zhongqi; Song, Huan; Tian, Dan; Wu, Jizhou; Zhan, Mengyao; Wang, Jianming (March 2022). "Risk factors for types of recurrent tuberculosis (reactivation versus reinfection): A global systematic review and meta-analysis". International journal of infectious diseases: IJID: official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 116: 14–20. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.12.344. ISSN 1878-3511. Archived from the original on 2022-06-19. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- 1 2 Martin, Sherry Joseph; Sabina, Evan Prince (2019). "Malnutrition and Associated Disorders in Tuberculosis and Its Therapy". Journal of Dietary Supplements. 16 (5): 602–610. doi:10.1080/19390211.2018.1472165. ISSN 1939-022X. Archived from the original on 20 January 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Tuberculosis (TB) - Treatment Regimens for Latent TB Infection". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 September 2022. Archived from the original on 30 May 2023. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ↑ "TB - Latent TB Infection (LTBI) in the U.S. - Published Estimates". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 21 January 2022. Archived from the original on 6 November 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- 1 2 "Inactive tuberculosis (Concept Id: C1609538) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ↑ Esmail, H.; Barry, C. E.; Young, D. B.; Wilkinson, R. J. (19 June 2014). "The ongoing challenge of latent tuberculosis". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 369 (1645): 20130437. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0437. ISSN 0962-8436. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- 1 2 Nuermberger, Eric; Bishai, William R.; Grosset, Jacques H. (June 2004). "Latent Tuberculosis Infection". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 25 (3): 317–336. doi:10.1055/s-2004-829504. ISSN 1069-3424. Archived from the original on 2023-11-07. Retrieved 2023-11-04.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis (TB) - Latent TB Infection and TB Disease". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 December 2020. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- 1 2 Adigun, Rotimi; Singh, Rahulkumar (2023). "Tuberculosis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 18 March 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ "Detailed Explanation of Tuberculosis (TB)". Niaid.nih.gov. 2009-03-06. Archived from the original on 2015-10-06. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "CDC issues Important info about TB exposure, explains tests here". Democratic Underground. Archived from the original on 2015-09-30. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "Chapter 3—The Facts About Tuberculosis". Chapter 3—The Facts About Tuberculosis – The Tuberculosis Epidemic – NCBI Bookshelf. Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 1995. Archived from the original on 2016-01-15. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis | University of Maryland Medical Center". Umm.edu. 2015-03-24. Archived from the original on 2015-10-04. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ For example, if you work in the Retirement Home industry in Ontario, Canada you are required by law to have a TB test to confirm that you do not have active TB cite - Ontario Regulation 166/11 s. 27 (8) (b)

- ↑ "Tuberculosis in Canada: Infographic (2021)". www.canada.ca. 16 March 2023. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- 1 2 Kelly E. Dooley; Tania Tang; Jonathan E. Golub; Susan E. Dorman; Wendy Cronin (2009). "Impact of diabetes mellitus on treatment outcomes of patients with active tuberculosis". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 80 (4): 634–639. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2009.80.634. PMC 2750857. PMID 19346391.

- 1 2 3 "Latent TB: FAQ's — EthnoMed". Ethnomed.org. Archived from the original on 2016-01-15. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ Behr, Marcel A.; Kaufmann, Eva; Duffin, Jacalyn; Edelstein, Paul H.; Ramakrishnan, Lalita (15 July 2021). "Latent Tuberculosis: Two Centuries of Confusion". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 204 (2): 142–148. doi:10.1164/rccm.202011-4239PP. ISSN 1535-4970. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "WHO | Tuberculosis". Who.int. 2015-03-09. Archived from the original on 2012-08-23. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- 1 2 3 4 Flynn, J. L.; Chan, J. (2001). "Tuberculosis: Latency and Reactivation". Infection and Immunity. 69 (7): 4195–201. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.7.4195-4201.2001. PMC 98451. PMID 11401954.

- ↑ Dale, Katie D; Karmakar, Malancha; Snow, Kathryn J; Menzies, Dick; Trauer, James M; Denholm, Justin T (October 2021). "Quantifying the rates of late reactivation tuberculosis: a systematic review". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 21 (10): e303–e317. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30728-3. Archived from the original on 2023-11-13. Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- 1 2 "Tuberculosis Symptoms, Causes & Risk Factors". American Lung Association. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ Tuberculosis at eMedicine

- ↑ "HIV and Tuberculosis (TB) | NIH". hivinfo.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ↑ Comstock, George W; Livesay, Verna T; Woolpert, Shirley F (1974). "The prognosis of a positive tuberculin reaction in childhood and adolescence". American Journal of Epidemiology. 99 (2): 131–8. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121593. PMID 4810628.

- ↑ "Diabetes and tuberculosis". idf.org. International Diabetes Federation. Archived from the original on August 27, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Risk Factors". The Mayo Clinic. July 12, 2013. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis | Doctor". Patient. 2014-05-21. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis". Mayo Clinic. 2014-08-01. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis". December 9, 2011. Archived from the original on September 6, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ↑ Andrews, Jason R.; Noubary, Farzad; Walensky, Rochelle P.; Cerda, Rodrigo; Losina, Elena; Horsburgh, C. Robert (March 2012). "Risk of progression to active tuberculosis following reinfection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 54 (6): 784–791. doi:10.1093/cid/cir951. ISSN 1537-6591. Archived from the original on 9 August 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ Deiss, Robert G.; Rodwell, Timothy C.; Garfein, Richard S. (January 2009). "Tuberculosis and Illicit Drug Use: Review and Update". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (1): 72–82. doi:10.1086/594126. Archived from the original on 2022-03-08. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- 1 2 3 4 Carranza, Claudia; Pedraza-Sanchez, Sigifredo; de Oyarzabal-Mendez, Eleane; Torres, Martha (2020). "Diagnosis for Latent Tuberculosis Infection: New Alternatives". Frontiers in Immunology. 11. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.02006/full. ISSN 1664-3224. Archived from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ "Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children" (PDF). CDC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ↑ Lewinsohn, David M.; Leonard, Michael K.; LoBue, Philip A.; Cohn, David L.; Daley, Charles L.; Desmond, Ed; Keane, Joseph; Lewinsohn, Deborah A.; Loeffler, Ann M.; Mazurek, Gerald H.; O’Brien, Richard J.; Pai, Madhukar; Richeldi, Luca; Salfinger, Max; Shinnick, Thomas M.; Sterling, Timothy R.; Warshauer, David M.; Woods, Gail L. (15 January 2017). "Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 64 (2): 111–115. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw778. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ↑ Corvino, Daniela F. de Lima; Shrestha, Sanjay; Kosmin, Aaron R. (8 August 2022). "Tuberculosis Screening". StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis: prevention, diagnosis, management and service organisation". NICE. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- 1 2 Dacso, Clifford C. (1990). "Skin Testing for Tuberculosis". Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations (3rd ed.). Butterworths. ISBN 978-0-409-90077-4. Archived from the original on 2019-12-17. Retrieved 2023-11-04.

- 1 2 3 Masterson, L; Srouji, I; Kent, R; Bath, A P (February 2011). "Nasal tuberculosis – an update of current clinical and laboratory investigation" (PDF). The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 125 (2): 210–213. doi:10.1017/S0022215110002136. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-05-03. Retrieved 2023-11-14.The Heaf test was discontinued in the UK in 2005.

- ↑ Takeda, Keita; Nagai, Hideaki; Suzukawa, Maho; Sekiguchi, Ryo; Akashi, Shunsuke; Sato, Ryota; Narumoto, Osamu; Kawashima, Masahiro; Suzuki, Junko; Ohshima, Nobuharu; Yamane, Akira; Tamura, Atsuhisa; Matsui, Hirotoshi; Tohma, Shigeto (November 2020). "Comparison of QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube, and T-SPOT.TB among patients with tuberculosis". Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy: Official Journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 26 (11): 1205–1212. doi:10.1016/j.jiac.2020.06.019. ISSN 1437-7780. Archived from the original on 4 November 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- 1 2 "Tuberculosis (TB) Fact Sheets- Tuberculin Skin Testing". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 12 July 2023. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ↑ "CDC | TB | Testing & Diagnosis". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-05. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "Well". Archived from the original on October 21, 2013 – via NYTimes.com.

- ↑ Heaf 1951, pp. 151–3.

- ↑ Anand, J. K.; Roberts, J. T. (May 1991). "Disposable tuberculin tests: available and needed. A review". Public Health. 105 (3): 257–259. doi:10.1016/s0033-3506(05)80116-7. ISSN 0033-3506. Archived from the original on 2023-11-04. Retrieved 2023-11-02.

- ↑ Galbraith, N. S.; Hanson, Audrey; Shoulman, R.; Andrews, D. W.; Lee, D. B. (1972). "Interpretation Of Positive Reactions To Heaf Tuberculin Test In London Schoolchildren". The British Medical Journal. 1 (5801): 647–649. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5801.647. ISSN 0007-1447. JSTOR 25417979. PMC 1787811. PMID 4622617.

- 1 2 "Guidelines for Using the QuantiFERON®-TB Gold Test for Detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection, United States". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ Banaei, Niaz; Gaur, Rajiv L.; Pai, Madhukar (April 2016). "Interferon Gamma Release Assays for Latent Tuberculosis: What Are the Sources of Variability?". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 54 (4): 845–850. doi:10.1128/JCM.02803-15. ISSN 1098-660X. Archived from the original on 2023-08-21. Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- ↑ "How the T-SPOT.TB Test Works". Archived from the original on 2020-02-04. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ↑ "Health Protection Agency position statement on the use of Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) tests for Tuberculosis (TB)" (PDF). Health Protection Agency position. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ Pérez-Lu, José E.; Cárcamo, Cesar P.; García, Patricia J.; Bussalleu, Alejandro; Bernabé-Ortiz, Antonio (March 2013). "Tuberculin skin test conversion among health sciences students: a retrospective cohort study". Tuberculosis (Edinburgh, Scotland). 93 (2): 257–262. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2012.10.001. ISSN 1873-281X. Archived from the original on 2022-04-08. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ↑ Baussano, Iacopo; Bugiani, Massimiliano; Carosso, Aurelia; Mairano, Dario; Barocelli, Anna Pia; Tagna, Marina; Cascio, Vincenza; Piccioni, Pavilio; Arossa, Walter (2007). "Risk of tuberculin conversion among healthcare workers and the adoption of preventive measures". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 64 (3): 161–166. doi:10.1136/oem.2006.028068. ISSN 1351-0711. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ↑ "Booster Phenomenon". Mass.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-10-06. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "CDC | TB | LTBI – Diagnosis of Latent TB Infection". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-10-01. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ Lardizabal, Alfred A.; Reichman, Lee B. (13 January 2021). "Diagnosis of Latent Tuberculosis Infection". Tuberculosis and Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections. Wiley: 75–82. doi:10.1128/9781555817138.ch5. Archived from the original on 19 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ↑ Al-Orainey, Ibrahim O. (January 2009). "Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis: Can we do better?". Annals of Thoracic Medicine. 4 (1): 5. doi:10.4103/1817-1737.44778. ISSN 1817-1737. Archived from the original on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis (TB) - Drug-Resistant TB". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 20 December 2022. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ↑ "CDC | TB | Fact Sheets | Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR TB)". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-10-03. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "CDC | TB | Fact sheets | Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (XDR TB)". Cdc.gov. 2013-01-18. Archived from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "Doctors Report Tuberculosis Now 'Virtually Untreatable' | Incurable TB Antibiotics". Livescience.com. 2013-02-12. Archived from the original on 2015-10-04. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- 1 2 Guidelines on the Management of Latent Tuberculosis Infection. World Health Organization. 2015. ISBN 978-92-4-154890-8. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis (TB) - Latent TB Infection Treatment FAQs for Clinicians". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 13 February 2020. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Treatment options for latent tuberculosis infection". Latent tuberculosis infection: updated and consolidated guidelines for programmatic management [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2018. Archived from the original on 19 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- 1 2 Efficacy of various durations of isoniazid preventive therapy for tuberculosis: five years of follow-up in the IUAT trial. International Union Against Tuberculosis Committee on Prophylaxis. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60(4):555-64.

- ↑ Schechter M, Zajdenverg R, Falco G, Barnes G, Faulhaber J, Coberly J, Moore R, Chaisson R (2006). "Weekly rifapentine/isoniazid or daily rifampin/pyrazinamide for latent tuberculosis in household contacts". Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 173 (8): 922–6. doi:10.1164/rccm.200512-1953OC. PMC 2662911. PMID 16474028.

- ↑ Timothy R. Sterling; M. Elsa Villarino; Andrey S. Borisov; Nong Shang; Fred Gordin; Erin Bliven-Sizemore; Judith Hackman; Carol Dukes Hamilton; Dick Menzies; Amy Kerrigan; Stephen E. Weis; Marc Weiner; Diane Wing; Marcus B. Conde; Lorna Bozeman; C. Robert Horsburgh, Jr.; Richard E. Chaisson (2011). "Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection". New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (23): 2155–2166. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1104875. PMID 22150035. S2CID 36515489.

- ↑ Recommendations for Use of an Isoniazid-Rifapentine Regimen with Direct Observation to Treat Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection Archived 2022-09-01 at the Wayback Machine. cdc.gov. updated November 22, 2013.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT01582711 for "Study 33: Adherence to Latent Tuberculosis Infection Treatment 3HP SAT Versus 3HP DOT (iAdhere)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- 1 2 Menzies, Dick; Al Jahdali, Hamdan; Al Otaibi, Badriah (2011). "Recent developments in treatment of latent tuberculosis infection". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 133 (3): 257–66. PMC 3103149. PMID 21441678. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- 1 2 3 4 "Countries Compared by Health > Tuberculosis cases > Per 100,000. International Statistics at". Nationmaster.com. Archived from the original on 2013-04-04. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis South America Cause Of Death". Worldlifeexpectancy.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-19. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ Dewan, Puneet K.; Lal, S. S.; Lonnroth, Knut; Wares, Fraser; Uplekar, Mukund; Sahu, Suvanand; Granich, Reuben; Chauhan, Lakhbir Singh (2006). "WHO | Tuberculosis in the WHO South-East Asia Region". BMJ. 332 (7541): 574–578. doi:10.1136/bmj.38738.473252.7C. PMC 1397734. PMID 16467347. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ Society, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Thoracic (1 October 2005). "BTS recommendations for assessing risk and for managing Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and disease in patients due to start anti-TNF-α treatment". Thorax. 60 (10): 800–805. doi:10.1136/thx.2005.046797. ISSN 0040-6376. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ↑ "Recommendations | Tuberculosis | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 13 January 2016. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ↑ Maugh II, Thomas H. (2011-05-17). "Shorter treatment found for latent tuberculosis". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2022-08-19. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

Although TB control measures in the United States have brought the incidence of the disease to an all-time low of 11,181 cases in 2010, it is estimated that at least 11 million Americans have latent TB. 'The 11 million Americans with latent TB represent a ticking time bomb,' Dr. Kenneth Castro, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's division of tuberculosis elimination, said at a news conference Monday. 'They're the source of future TB cases.'

- ↑ Behr, Marcel A.; Edelstein, Paul H.; Ramakrishnan, Lalita (August 23, 2018). "Revisiting the timetable of tuberculosis". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 362: k2738. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2738. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 6105930. PMID 30139910.

- ↑ Behr, Marcel A.; Edelstein, Paul H.; Ramakrishnan, Lalita (2019-10-24). "Is Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection life long?". BMJ. 367: l5770. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5770. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 6812595. PMID 31649096.

- 1 2 McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (20 September 2018). "'Latent' tuberculosis? It's not that common, experts find". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ Corrigenda (25 May 2022) Global tuberculosis report 2021 (PDF). World Health Organization. 14 October 2021. ISBN 978-92-4-003702-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 14 May 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Further reading

- Jasmer, R. M.; Nahid, P.; Hopewell, P. C. (2002). "Latent tuberculosis infection". New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (23): 1860–1866. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp021045. PMID 12466511.

- Mazurek, G. H.; Villarino, M. E. (2003). "Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB test for diagnosing latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 52 (RR–2): 15–18.

- Ormerod, P.; Skinner, C.; Moore-Gillon, J.; Davies, P.; Connolly, M. (2000). "BTS Guidelines: control and prevention of tuberculosis in the United Kingdom: Code of Practice 2000". Thorax. 55 (11): 887–901. doi:10.1136/thorax.55.11.887. PMC 1745632. PMID 11050256. Archived from the original on 2006-06-15. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

External links

| Classification |

|---|