McGillivray syndrome

| McGillivray syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Familial scaphocephaly syndrome, McGillivray type, Scaphocephaly-macrocephaly-maxillary retrusion-intellectual disability syndrome |

| |

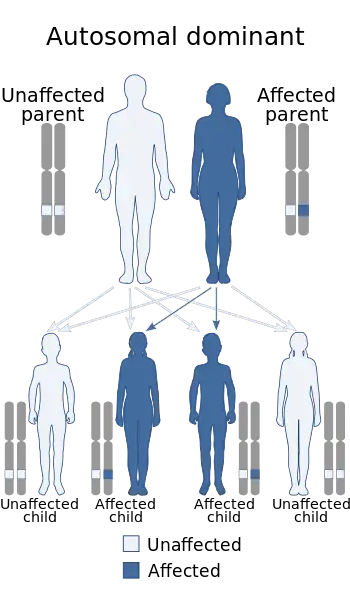

| This condition is inherited via an autosomal dominant manner | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

McGillivray syndrome is a rare syndrome characterized mainly by heart defects, skull and facial abnormalities and ambiguous genitalia. The symptoms of this syndrome are ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, small jaw, undescended testes, and webbed fingers. Beside to these symptoms there are more symptoms which is related with bone structure and misshape.

McGillivray syndrome is a birth defect in which one or more of the joints between the bones of the baby's skull close prematurely, before the baby's brain is fully formed. When the baby has craniosynostosis, his or her brain cannot grow in its natural shape and the head is misshapen. It can affect one or more of the joints in the baby's skull. In some cases, craniosynostosis is associated with an underlying brain abnormality that prevents the brain from growing properly. Treating McGillivray usually involves surgery to separate the fused bones. If there is no underlying brain abnormality, the surgery allows the baby's brain to grow and develop in adequate space.

Symptoms and signs

The baby's skull has seven bones. Normally, these bones don't fuse until around age 2, giving the baby's brain time to grow. Joints called cranial sutures, made of strong, fibrous tissue, hold these bones together. In the front of the baby's skull, the sutures intersect in the large soft spot (fontanel) on the top of the baby's head. Normally, the sutures remain flexible until the bones fuse. The signs of craniosynostosis may not be noticeable at birth, but they become apparent during the first few months of the baby's life. The symptoms differs from types of synostosis. First of all there is Sagittal synostosis (scaphocephaly). Premature fusion of the suture at the top of the head (sagittal suture) forces the head to grow long and narrow, rather than wide. Scaphocephaly is the most common type of craniosynostosis. The other one is called Coronal synostosis (anterior plagiocephaly). Premature fusion of a coronal suture — one of the structures that run from each ear to the sagittal suture on top of the head — may force the baby's forehead to flatten on the affected side. It may also raise the eye socket and cause a deviated nose and slanted skull. The Bicoronal synostosis (brachycephaly). When both of the coronal sutures fuse prematurely, the baby may have a flat, elevated forehead and brow.

Cause

Diagnosis

First of all there is physical exam. Doctors examine the baby's head for abnormalities such as suture ridges and look the facial deformities. Also, they utilizes Computerized Tomography which scan of the baby's skull. Fused sutures are identifiable by their absences. X-rays also may be used to measure precise dimensions of the baby's skull, using a technique called cephalometry.

Genetic testing. If the doctor suspects the baby's misshapen skull is caused by an underlying hereditary syndrome, genetic testing may help identify the syndrome. Genetic tests usually require a blood sample. Depending on what type of abnormality is suspected, the doctor may take a sample of the baby's hair, skin or other tissue, such as cells from the inside of the cheek. The sample is sent to a lab for analysis.

Rare types

There are two less common types of McGillivray syndromes are: Metopic synostosis (trigonocephaly). The metopic suture runs from the baby's nose to the sagittal suture. Premature fusion gives the scalp a triangular appearance. Another one is Lambdoid synostosis (posterior plagiocephaly). This rare form of craniosynostosis involves the lambdoid suture, which runs across the skull near the back of the head. It may cause flattening of the baby's head on the affected side. A misshapen head doesn't always indicate craniosynostosis. For example, if the back of the baby's head appears flattened, it could be the result of birth trauma or the baby's spending too much time on his or her back. This condition is sometimes treated with a custom-fit helmet that helps mold the baby's head back into a normal position.

Treatments

The major treatment is surgery for most babies. The type of surgery which they would undergo differs from age and strength they have. The main reason of doing the surgery is to alleviate pressure on the brain, and create a space for brain developing and growing. It would improve infant's appearance.

The first one is Traditional surgery. During surgery, they make an incision in the baby's scalp and cranial bones, and reshape the portion of the skull. Sometimes plates and screws, often made of material that is absorbed over time, are used to hold the bones in place. Surgery, which is performed during general anesthesia, usually takes hours.

After surgery, the baby remains in the hospital for at least three days. Some children may require a second surgery later because, the craniosynostosis reoccurs. Also, children with facial deformities often require future surgeries to reshape their faces.

Another one is Endoscopic surgery. This less invasive form of surgery isn't an option for everyone. But in certain cases, the surgeon may use a lighted tube (endoscope) inserted through one or two small scalp incisions over the affected suture. The surgeon then opens the suture to enable the baby's brain to grow normally. Endoscopic surgery usually takes about an hour, causes less swelling and blood loss, and shortens the hospital stay, often to one day after surgery.

History

McGillivray Syndrome is referenced from the 1851 writings of Virchow. His understanding and descriptions of irregular calvarial growth patterns were the basis of the law of Virchow. According to his observations, the abnormal cranial growth observed in persons with craniosynostosis occurs perpendicular to the involved calvarial sutures. Therefore, if a suture line is prematurely ossified, no growth is present in the direction perpendicular to that suture. Surgical treatment for craniosynostosis was initially advocated by Odilon Lannelongue in 1890.

His patients had microcephaly from craniosynostosis and were thought to be imbeciles. These patients accordingly underwent craniectomy to remove the involved suture line and to "release the brain". Soon after, in 1891, linear craniectomy was introduced. As with any new procedure, this one met with much resistance. However, the resistance to a surgical intervention was slowly put to rest with mounting evidence. Several studies indicated that craniosynostectomy was the treatment of choice for the release of fused suture lines in the skull. Studies showed that, over time, cranial suture areas excised during strip craniectomy still became fused and led to an abnormal cranial contour.

Strip craniectomy was easier and involved less blood loss compared with the newer cranial vault reconstruction. Strip craniectomy also did not address the frontal bossing and associated abnormalities in calvarial shape and relied on the rapid growth of the brain to correct it. Strip craniectomy was optimal only in the first few months of infancy, while surgeons could use cranial vault reconstruction throughout infancy. Consequently, strip craniectomy lost favor, and the surgical treatment has been modified to include cranial vault remodeling. Recently, with the advent of endoscopy, attention has returned to endoscopic strip craniectomy. The endoscopic technique has only been tried over the last several years, but it offers the advantages of a shorter and safer operation, less cost, less in-hospital time, and less blood loss. The operation was shown to be a success in a study of 12 patients, all younger than 8 months. Critical to this success and a departure from the standard strip craniosynostectomy was the extensive use of a postoperative remodeling helmet. Although first introduced by Persing et al. in 1986, helmet therapy has not been used as extensively as a postoperative therapeutic intervention.

References

- "Craniosynostosis." - Mayo Clinic. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Mar. 2016.

- "Craniosynostosis Management." : Overview, History, Pathogenesis. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Mar. 2016.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. Johns Hopkins Hospital, n.d. Web.

- "Symptoms of McGillivray Syndrome." - RightDiagnosis.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 06 Mar. 2016.

- "The Craniosynostoses." Google Books. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Mar. 2016.

External links

- McGillivray syndrome - NCBI

- McGillivray syndrome - Office of Rare Disease Research, NCBI