Nitroglycerin (chemical)

| |

.png.webp) | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Propane-1,2,3-triyl trinitrate | |

| Other names

*1,2,3-Tris(nitrooxy)propane

| |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

Beilstein Reference |

1802063 |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| EC Number |

|

Gmelin Reference |

165859 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Nitroglycerin |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 0143, 0144, 1204, 3064, 3319 |

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C3H5N3O9 |

| Molar mass | 227.085 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid |

| Density | 1.6 g⋅cm−3 (at 15 °C) |

| Melting point | 14 °C (57 °F; 287 K) |

| Boiling point | 50 °C (122 °F; 323 K) Explodes |

Solubility in water |

Slightly[1] |

| Solubility | Acetone, ether, benzene, alcohol[1] |

| log P | 2.154 |

| Structure | |

Coordination geometry |

|

Molecular shape |

|

| Explosive data | |

| Shock sensitivity | High |

| Friction sensitivity | High |

| Detonation velocity | 7700 m⋅s−1 |

| RE factor | 1.50 |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−370 kJ⋅mol−1 |

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−1.529 MJ⋅mol−1 |

| Pharmacology | |

| C01DA02 (WHO) C05AE01 (WHO) | |

| Intravenous, by mouth, under the tongue, topical | |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| <1% | |

| Liver | |

| 3 min | |

| Legal status |

|

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Explosive, toxic |

| GHS pictograms |     |

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

GHS hazard statements |

H202, H205, H241, H301, H311, H331, H370 |

GHS precautionary statements |

P210, P243, P250, P260, P264, P270, P271, P280, P302+352, P410 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

C 0.2 ppm (2 mg/m3) [skin][2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

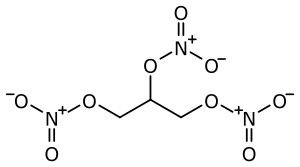

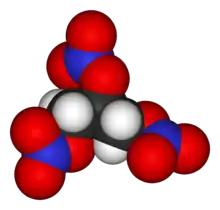

Nitroglycerin (NG), also known as nitroglycerine, trinitroglycerin (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by nitrating glycerol with white fuming nitric acid under conditions appropriate to the formation of the nitric acid ester. Chemically, the substance is an organic nitrate compound rather than a nitro compound, but the traditional name is retained. Invented in 1847 by Ascanio Sobrero, nitroglycerin has been used ever since as an active ingredient in the manufacture of explosives, namely dynamite, and as such it is employed in the construction, demolition, and mining industries. Since the 1880s, it has been used by the military as an active ingredient and gelatinizer for nitrocellulose in some solid propellants such as cordite and ballistite. It is a major component in double-based smokeless propellants used by reloaders. Combined with nitrocellulose, hundreds of powder combinations are used by rifle, pistol, and shotgun reloaders.

Nitroglycerin has been used for over 130 years in medicine as a potent vasodilator (dilation of the vascular system) to treat heart conditions, such as angina pectoris and chronic heart failure. Though it was previously known that these beneficial effects are due to nitroglycerin being converted to nitric oxide, a potent venodilator, the enzyme for this conversion was only discovered to be mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) in 2002.[4] Nitroglycerin is available in sublingual tablets, sprays, ointments, and patches.[5]

History

Nitroglycerin was the first practical explosive produced that was stronger than black powder. It was first synthesized by the Italian chemist Ascanio Sobrero in 1847, working under Théophile-Jules Pelouze at the University of Turin.[6] Sobrero initially called his discovery pyroglycerine and warned vigorously against its use as an explosive.[7]

Nitroglycerin was later adopted as a commercially useful explosive by Alfred Nobel, who experimented with safer ways to handle the dangerous compound after his younger brother, Emil Oskar Nobel, and several factory workers were killed in an explosion at the Nobels' armaments factory in 1864 in Heleneborg, Sweden.[8]

One year later, Nobel founded Alfred Nobel and Company in Germany and built an isolated factory in the Krümmel hills of Geesthacht near Hamburg. This business exported a liquid combination of nitroglycerin and gunpowder called "Blasting Oil", but this was extremely unstable and difficult to handle, as evidenced in numerous catastrophes. The buildings of the Krümmel factory were destroyed twice.[9]

In April 1866, three crates of nitroglycerin were shipped to California for the Central Pacific Railroad, which planned to experiment with it as a blasting explosive to expedite the construction of the 1,659-foot-long (506 m) Summit Tunnel through the Sierra Nevada Mountains. One of the crates exploded, destroying a Wells Fargo company office in San Francisco and killing 15 people. This led to a complete ban on the transportation of liquid nitroglycerin in California. The on-site manufacture of nitroglycerin was thus required for the remaining hard-rock drilling and blasting required for the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in North America.[10]

In June 1869, two one-ton wagons loaded with nitroglycerin, then known locally as Powder-Oil, exploded in the road at the North Wales village of Cwm-y-glo. The explosion led to the loss of six lives, many injuries and much damage to the village. Little trace was found of the two horses. The UK Government was so alarmed at the damage caused and what could have happened in a city location (these two tons were part of a larger load coming from Germany via Liverpool) that they soon passed The Nitro-Glycerine Act of 1869.[11] Liquid nitroglycerin was widely banned elsewhere, as well, and these legal restrictions led to Alfred Nobel and his company's developing dynamite in 1867. This was made by mixing nitroglycerin with diatomaceous earth ("Kieselguhr" in German) found in the Krümmel hills. Similar mixtures, such as "dualine" (1867), "lithofracteur" (1869), and "gelignite" (1875), were formed by mixing nitroglycerin with other inert absorbents, and many combinations were tried by other companies in attempts to get around Nobel's tightly held patents for dynamite.

Dynamite mixtures containing nitrocellulose, which increases the viscosity of the mix, are commonly known as "gelatins".

Following the discovery that amyl nitrite helped alleviate chest pain, the physician William Murrell experimented with the use of nitroglycerin to alleviate angina pectoris and to reduce the blood pressure. He began treating his patients with small diluted doses of nitroglycerin in 1878, and this treatment was soon adopted into widespread use after Murrell published his results in the journal The Lancet in 1879.[12][13] A few months before his death in 1896, Alfred Nobel was prescribed nitroglycerin for this heart condition, writing to a friend: "Isn't it the irony of fate that I have been prescribed nitro-glycerin, to be taken internally! They call it Trinitrin, so as not to scare the chemist and the public."[14] The medical establishment also used the name "glyceryl trinitrate" for the same reason.

Wartime production rates

Large quantities of nitroglycerin were manufactured during World War I and World War II for use as military propellants and in military engineering work. During World War I, HM Factory, Gretna, the largest propellant factory in Britain, produced about 800 tonnes of cordite RDB per week. This amount required at least 336 tonnes of nitroglycerin per week (assuming no losses in production). The Royal Navy had its own factory at the Royal Navy Cordite Factory, Holton Heath, in Dorset, England. A large cordite factory was also built in Canada during World War I. The Canadian Explosives Limited cordite factory at Nobel, Ontario, was designed to produce 1,500,000 lb (680 t) of cordite per month, requiring about 286 tonnes of nitroglycerin per month.

Instability and desensitization

In its pure form, nitroglycerin is a contact explosive, with physical shock causing it to explode. This makes nitroglycerin highly dangerous to transport or use. In its undiluted form, it is one of the world's most powerful explosives, comparable to the more recently developed RDX and PETN.

Early in its history, liquid nitroglycerin was found to be "desensitized" by freezing it, at a temperature below 45 to 55 °F (7 to 13 °C) depending on its purity.[15] Its sensitivity to shock while frozen is somewhat unpredictable: "It is more insensitive to the shock from a fulminate cap or a rifle ball when in that condition but on the other hand it appears to be more liable to explode on breaking, crushing, tamping, etc."[16] Frozen nitroglycerine is much less energetic than liquid, and so must be thawed before use.[17] Thawing it out can be extremely sensitizing, especially if impurities are present or the warming is too rapid.[18] Ethylene glycol dinitrate or another polynitrate may be added to lower the melting and thereby avoid the necessity of thawing frozen explosive.[19]

Chemically "desensitizing" nitroglycerin is possible to a point where it can be considered about as "safe" as modern high explosives, such as by the addition of ethanol, acetone, or dinitrotoluene.[20] The nitroglycerine may have to be extracted from the desensitizer chemical to restore its effectiveness before use, for example by adding water to draw off ethanol used as a desensitizer.[20]

Detonation

Nitroglycerin and any diluents can certainly deflagrate (burn). The explosive power of nitroglycerin derives from detonation: energy from the initial decomposition causes a strong pressure wave that detonates the surrounding fuel. This is a self-sustained shock wave that propagates through the explosive medium at 30 times the speed of sound as a near-instantaneous pressure-induced decomposition of the fuel into a white-hot gas. Detonation of nitroglycerin generates gases that would occupy more than 1,200 times the original volume at ordinary room temperature and pressure. The heat liberated raises the temperature to about 5,000 °C (9,000 °F).[19] This is entirely different from deflagration, which depends solely upon available fuel regardless of pressure or shock. The decomposition results in much higher ratio of energy to gas moles released compared to other explosives, making it one of the hottest detonating high explosives.

Manufacturing

Nitroglycerin can be produced by acid-catalyzed nitration of glycerol (glycerin).

The industrial manufacturing process often reacts glycerol with a nearly 1:1 mixture of concentrated sulfuric acid and concentrated nitric acid. This can be produced by mixing white fuming nitric acid—a quite expensive pure nitric acid in which the oxides of nitrogen have been removed, as opposed to red fuming nitric acid, which contains nitrogen oxides—and concentrated sulfuric acid. More often, this mixture is attained by the cheaper method of mixing fuming sulfuric acid, also known as oleum—sulfuric acid containing excess sulfur trioxide—and azeotropic nitric acid (consisting of about 70% nitric acid, with the rest being water).

The sulfuric acid produces protonated nitric acid species, which are attacked by glycerol's nucleophilic oxygen atoms. The nitro group is thus added as an ester C−O−NO2 and water is produced. This is different from an electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction in which nitronium ions are the electrophile.

The addition of glycerol results in an exothermic reaction (i.e., heat is produced), as usual for mixed-acid nitrations. If the mixture becomes too hot, it results in a runaway reaction, a state of accelerated nitration accompanied by the destructive oxidation of organic materials by the hot nitric acid and the release of poisonous nitrogen dioxide gas at high risk of an explosion. Thus, the glycerin mixture is added slowly to the reaction vessel containing the mixed acid (not acid to glycerin). The nitrator is cooled with cold water or some other coolant mixture and maintained throughout the glycerin addition at about 22 °C (72 °F), much below which the esterification occurs too slowly to be useful. The nitrator vessel, often constructed of iron or lead and generally stirred with compressed air, has an emergency trap door at its base, which hangs over a large pool of very cold water and into which the whole reaction mixture (called the charge) can be dumped to prevent an explosion, a process referred to as drowning. If the temperature of the charge exceeds about 30 °C (86 °F) (actual value varying by country) or brown fumes are seen in the nitrator's vent, then it is immediately drowned.

Use as an explosive and a propellant

The main use of nitroglycerin, by tonnage, is in explosives such as dynamite and in propellants.

Nitroglycerin is an oily liquid that may explode when subjected to heat, shock, or flame.

Alfred Nobel developed the use of nitroglycerin as a blasting explosive by mixing nitroglycerin with inert absorbents, particularly "Kieselguhr", or diatomaceous earth. He named this explosive dynamite and patented it in 1867.[24] It was supplied ready for use in the form of sticks, individually wrapped in greased waterproof paper. Dynamite and similar explosives were widely adopted for civil engineering tasks, such as in drilling highway and railroad tunnels, for mining, for clearing farmland of stumps, in quarrying, and in demolition work. Likewise, military engineers have used dynamite for construction and demolition work.

Nitroglycerin was also used as an ingredient in military propellants for use in firearms.

Nitroglycerin has been used in conjunction with hydraulic fracturing, a process used to recover oil and gas from shale formations. The technique involves displacing and detonating nitroglycerin in natural or hydraulically induced fracture systems, or displacing and detonating nitroglycerin in hydraulically induced fractures followed by wellbore shots using pelletized TNT.[25]

Nitroglycerin has an advantage over some other high explosives that on detonation it produces practically no visible smoke. Therefore, it is useful as an ingredient in the formulation of various kinds of smokeless powder.[26]

Its sensitivity has limited the usefulness of nitroglycerin as a military explosive, and less sensitive explosives such as TNT, RDX, and HMX have largely replaced it in munitions. It remains important in military engineering, and combat engineers still use dynamite.

Alfred Nobel then developed ballistite, by combining nitroglycerin and guncotton. He patented it in 1887. Ballistite was adopted by a number of European governments, as a military propellant. Italy was the first to adopt it. The British government and the Commonwealth governments adopted cordite instead, which had been developed by Sir Frederick Abel and Sir James Dewar of the United Kingdom in 1889. The original Cordite Mk I consisted of 58% nitroglycerin, 37% guncotton, and 5.0% petroleum jelly. Ballistite and cordite were both manufactured in the forms of "cords".

Smokeless powders were originally developed using nitrocellulose as the sole explosive ingredient. Therefore, they were known as single-base propellants. A range of smokeless powders that contains both nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin, known as double-base propellants, were also developed. Smokeless powders were originally supplied only for military use, but they were also soon developed for civilian use and were quickly adopted for sports. Some are known as sporting powders. Triple-base propellants contain nitrocellulose, nitroglycerin, and nitroguanidine, but are reserved mainly for extremely high-caliber ammunition rounds such as those used in tank cannons and naval artillery. Blasting gelatin, also known as gelignite, was invented by Nobel in 1875, using nitroglycerin, wood pulp, and sodium or potassium nitrate. This was an early, low-cost, flexible explosive.

Medical use

Nitroglycerin belongs to a group of drugs called nitrates, which includes many other nitrates like isosorbide dinitrate (Isordil) and isosorbide mononitrate (Imdur, Ismo, Monoket).[27] These agents all exert their effect by being converted to nitric oxide in the body by mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2),[4] and nitric oxide is a potent natural vasodilator.

In medicine, nitroglycerin is used for angina pectoris, a painful symptom of ischemic heart disease caused by inadequate flow of blood and oxygen to the heart and as a potent antihypertensive agent. Nitroglycerin corrects the imbalance between the flow of oxygen and blood to the heart and the heart’s energy demand.[27] At low doses, nitroglycerin dilates veins more than arteries, thereby reducing preload (volume of blood in the heart after filling); this is thought to be its primary mechanism of action. By decreasing preload, the heart has less blood to pump, which decreases oxygen requirement since the heart does not have to work as hard. Additionally, having a smaller preload reduces the ventricular transmural pressure (pressure exerted on the walls of the heart), which decreases the compression of heart arteries to allow more blood to flow through the heart. At higher doses, it also dilates arteries, thereby reducing afterload (decreasing the pressure against which the heart must pump).[27] An improved ratio of myocardial oxygen demand to supply leads to the following therapeutic effects during episodes of angina pectoris: subsiding of chest pain, decrease of blood pressure, increase of heart rate, and orthostatic hypotension. Patients experiencing angina when doing certain physical activities can often prevent symptoms by taking nitroglycerin 5 to 10 minutes before the activity. Overdoses may generate methemoglobinemia.[28][29]

Nitroglycerin is available in tablets, ointment, solution for intravenous use, transdermal patches, or sprays administered sublingually. Some forms of nitroglycerin last much longer in the body than others. Continuous exposure to nitrates has been shown to cause the body to stop responding normally to this medicine. Experts recommend that the patches be removed at night, allowing the body a few hours to restore its responsiveness to nitrates. Shorter-acting preparations of nitroglycerin can be used several times a day with less risk of developing tolerance.[30] Nitroglycerin was first used by William Murrell to treat angina attacks in 1878, with the discovery published that same year.[13][31]

Industrial exposure

Infrequent exposure to high doses of nitroglycerin can cause severe headaches known as "NG head" or "bang head". These headaches can be severe enough to incapacitate some people; however, humans develop a tolerance to and dependence on nitroglycerin after long-term exposure. Although rare, withdrawal can be fatal.[32] Withdrawal symptoms include chest pain and other heart problems. These symptoms may be relieved with re-exposure to nitroglycerin or other suitable organic nitrates.[33]

For workers in nitroglycerin (NTG) manufacturing facilities, the effects of withdrawal sometimes include "Sunday heart attacks" in those experiencing regular nitroglycerin exposure in the workplace, leading to the development of tolerance for the venodilating effects. Over the weekend, the workers lose the tolerance, and when they are re-exposed on Monday, the drastic vasodilation produces a fast heart rate, dizziness, and a headache. This is referred to as "Monday disease."[34][35]

People can be exposed to nitroglycerin in the workplace by breathing it in, skin absorption, swallowing it, or eye contact. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for nitroglycerin exposure in the workplace as 0.2 ppm (2 mg/m3) skin exposure over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has set a recommended exposure limit of 0.1 mg/m3 skin exposure over an 8-hour workday. At levels of 75 mg/m3, nitroglycerin is immediately dangerous to life and health.[36]

See also

|

|

References

- 1 2 "Occupational Safety and Health Guideline for Nitroglycerin". Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0456". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Hazard Rating Information for NFPA Fire Diamonds". Archived from the original on 17 February 2015.

- 1 2 Chen, Z.; Foster, M. W.; Zhang, J.; Mao, L.; Rockman, H. A.; Kawamoto, T.; Kitagawa, K.; Nakayama, K. I.; Hess, D. T.; Stamler, J. S. (2005). "An essential role for mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase in nitroglycerin bioactivation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (34): 12159–12164. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10212159C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503723102. PMC 1189320. PMID 16103363.

- ↑ "Unknown, behind paywall, archived". Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ↑ Sobrero, Ascagne (1847). "Sur plusieur composés détonants produits avec l'acide nitrique et le sucre, la dextrine, la lactine, la mannite et la glycérine" [On several detonating compounds produced with nitric acid and sugar, dextrin, lactose, mannitol, and glycerin]. Comptes Rendus. 24: 247–248. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ↑ Sobrero, Ascanio (1849). "Sopra alcuni nuovi composti fulminanti ottenuti col mezzo dell'azione dell'acido nitrico sulle sostante organiche vegetali" [On some new explosive products obtained by the action of nitric acid on some vegetable organic substances]. Memorie della Reale Accademia delle Scienze di Torino. 2nd Series. 10: 195–201. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2021. On p. 197, Sobrero names nitroglycerin "pyroglycerine":

- "Quelle gocciole costituiscono il corpo nuovo di cui descriverò ora le proprietà, e che chiamerò Piroglicerina." (Those drops constitute the new substance whose properties I will now describe, and which I will call "pyroglycerine".)

- ↑ "Emil Nobel". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- ↑ "Krümmel". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 10 July 2006..

- ↑ "Transcontinental Railroad – People & Events: Nitroglycerin". American Experience. PBS. Archived from the original on 12 February 2003. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ↑ North Wales Daily Post newspaper of October 14th 2018.

- ↑ Murrell, William (1879). "Nitroglycerin as a remedy for angina pectoris". The Lancet. 1 (2890): 80–81, 113–115, 151–152, 225–227. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)46032-1. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- 1 2 Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-89980-8.

- ↑ "History of TNG". beyonddiscovery.org. Archived from the original on 1 November 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ↑ Tallini, Rick F. "Frozen Nitroglycerin". Tales of Destruction. Analog Services, Inc. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|series-link=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|series-number=ignored (help) - ↑ Hurter, Charles S. (22 August 1911). "Accidents in the Transportation, Storage, and Use of Explosives" (PDF). Proceedings of the Lake Superior Mining Institute. 16: 70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ↑ Hurter, Charles S. (22 August 1911). "Accidents in the Transportation, Storage, and Use of Explosives" (PDF). Proceedings of the Lake Superior Mining Institute. 16: 71. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ↑ Tallini, Rick F. "Thawing can be Hell". Tales of Destruction. Analog Services, Inc. Archived from the original on 22 February 2001. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|series-link=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|series-number=ignored (help) - 1 2 "Nitroglycerin". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 12 September 2002. Retrieved 23 March 2005.

- 1 2 Tallini, Rick F. "Is Nitroglycerin in This?". Tales of Destruction. Analog Services, Inc. Archived from the original on 22 February 2001. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|series-link=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|series-number=ignored (help) - ↑ "Zusammensetzung der Zuckerasche" [Composition of sugar ash]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 64 (3): 398–399. 1848. doi:10.1002/jlac.18480640364.

- ↑ "Ueber Nitroglycerin". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 92 (3): 305–306. 1854. doi:10.1002/jlac.18540920309.

- ↑ Di Carlo, F. J. (1975). "Nitroglycerin Revisited: Chemistry, Biochemistry, Interactions". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 4 (1): 1–38. doi:10.3109/03602537508993747. PMID 812687.

- ↑ Bellis, Mary. "Alfred Nobel and the History of Dynamite". About.com Money. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ↑ Miller, J. S.; Johansen, R. T. (1976). "Fracturing Oil Shale with Explosives for In Situ Recovery" (PDF). Shale Oil, Tar Sand and Related Fuel Sources: 151. Bibcode:1976sots.rept...98M. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ↑ "Nitroglycerin". Archived from the original on 5 January 2003. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 Ogbru, Omudhome. "nitroglycerin, Nitro-Bid: Drug Facts, Side Effects and Dosing". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 27 March 2003. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ↑ Kaplan, K. J.; Taber, M.; Teagarden, J. R.; Parker, M.; Davison, R. (1985). "Association of methemoglobinemia and intravenous nitroglycerin administration". American Journal of Cardiology. 55 (1): 181–183. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(85)90324-8. PMID 3917597.

- ↑ "IntraMed – Bienvenido". www.intramed.net. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ↑ "Nitroglycerin for angina, February 1997, Vol. 7". Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- ↑ Smith, E.; Hart, F. D. (1971). "William Murrell, physician and practical therapist". British Medical Journal. 3 (5775): 632–633. doi:10.1136/bmj.3.5775.632. PMC 1798737. PMID 4998847.

- ↑ Amdur, Mary O.; Doull, John (1991). Casarett and Doull's Toxicology (4th ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0071052399.

- ↑ Sullivan, John B., Jr.; Krieger, Gary R. (2001). Clinical Environmental Health and Toxic Exposures: Latex. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-683-08027-8. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ Marsh, N.; Marsh, A. (2000). "A short history of nitroglycerine and nitric oxide in pharmacology and physiology". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 27 (4): 313–319. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03240.x. PMID 10779131. S2CID 12897126.

- ↑ Assembly of Life Sciences (U.S.) Advisory Center on Toxicology. Toxicological Reports. National Academies. p. 115. NAP:11288. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ "Nitroglycerine". NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. CDC. Archived from the original on 8 October 1999. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

External links

- "Nitroglycerine! Terrible Explosion and Loss of Lives in San Francisco". Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum. Archived from the original on 9 April 2001. Retrieved 23 March 2005. – 1866 Newspaper article

- WebBook page for C3H5N3O9 Archived 1 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards Archived 8 October 1999 at the Wayback Machine

- The Tallini Tales of Destruction Archived 19 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine Detailed and horrific stories of the historical use of nitroglycerin-filled torpedoes to restart petroleum wells.

- Dynamite and TNT Archived 30 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)