Hypertelorism

| Hypertelorism | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Ocular hypertelorism,[1] orbital hypertelorism,[1] hypertelorbitism[2] |

| |

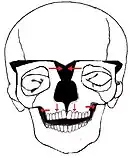

| Hypertelorism as seen in craniofrontonasal dysplasia | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

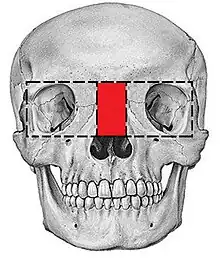

Hypertelorism is an abnormally increased distance between two organs or bodily parts, usually referring to an increased distance between the orbits (eyes), or orbital hypertelorism. In this condition the distance between the inner eye corners as well as the distance between the pupils is greater than normal. Hypertelorism should not be confused with telecanthus, in which the distance between the inner eye corners is increased but the distances between the outer eye corners and the pupils remain unchanged.[3]

Hypertelorism is a symptom in a variety of syndromes, including Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18), 1q21.1 duplication syndrome, basal cell nevus syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome and Loeys–Dietz syndrome. Hypertelorism can also be seen in Apert syndrome, Autism spectrum disorder, craniofrontonasal dysplasia, Noonan syndrome, neurofibromatosis,[4] LEOPARD syndrome, Crouzon syndrome, Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome, Andersen–Tawil syndrome, Waardenburg syndrome and cri du chat syndrome, along with piebaldism, prominent inner third of the eyebrows, irises of different color, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, mucopolysaccharide metabolism disorders (Morquio syndrome and Hurler's syndrome), deafness and also in hypothyroidism. Some links have been found between hypertelorism and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Embryology

Because hypertelorism is an anatomic condition associated with a heterogeneous group of congenital disorders, it is believed that the underlying mechanism of hypertelorism is also heterogeneous. Theories include too early ossification of the lower wings of the sphenoid, an increased space between the orbita, due to increasing width of the ethmoid sinuses, field defects during the development, a nasal capsule that fails to form, leading to a failure in normal medial orbital migration and also a disturbance in the formation of the cranial base, which can be seen in syndromes like Apert and Crouzon.[3]

Treatment

The craniofacial surgery to correct hypertelorism is usually done between five and eight years of age. This aesthetic-focused procedure addresses the psychosocial aspects in the child's early school years. Another reason for a correction age of five years or older is that the surgery should be delayed until the tooth buds have grown out low enough into the maxilla, thus preventing damage to them. Also, before age five the craniofacial bones are thin and fragile, which can make surgical correction difficult. In addition, it is possible that orbital surgery during infancy may inhibit midface growth.[3]

For the treatment of hypertelorism there are two main operative options: The box osteotomy and the facial bipartition (also referred to as median fasciotomy).[5]

Box osteotomy

This treatment of orbital hypertelorism was first performed by Paul Tessier.[6] The surgery starts off by various osteotomies that separate the entire bony part of the orbit from the skull and surrounding facial bones. One of the osteotomies consists of removing the bone between the orbits. The orbits are then mobilized and brought towards each other. Because this often creates excessive skin between the orbits a midline excision of skin is frequently necessary. This approximates the eyebrows and eye corners and provides a more pleasing look.[3]

Facial bipartition

The standard procedure (box osteotomy) was modified by Jacques van der Meulen and resulted in the development of the facial bipartition (or median faciotomy).[7][8] Facial bipartition first involves splitting the frontal bone from the supraorbital rim. Then the orbits and the midface are released from the skull-base using monoblock osteotomy. Then a triangular shaped piece of bone is removed from the midline of the midface. The base of this triangular segment lies above the orbita and the apex lies between the upper incisor teeth. After removing this segment it is possible to rotate the two halves of the midface towards each other, thus resulting in reduction of the distance between the orbits. It also results in leveling out the V-shaped maxilla and therefore widening of it. Because hypertelorism is often associated with syndromes like Apert, hypertelorism is often seen in combination with midface dysplasia. If this is the case, facial bipartition can be combined with distraction osteogenesis. The aim of distraction osteogenesis of the midface is to normalize the relationship between orbital rim to eye and also normalize the position of zygomas, nose and maxilla in relation to the mandible.[9]

Soft tissue reconstruction

To create an acceptable aesthetic result in the correction of orbital hypertelorism, it is also important to take soft-tissue reconstruction in consideration. In this context, correction of the nasal deformities is one of the more difficult procedures. Bone and cartilage grafts may be necessary to create a nasal frame and local rotation with for example forehead flaps, or advancement flaps can be used to cover the nose.[3]

Complications from surgery

As with almost every kind of surgery, the main complications in both treatments of hypertelorism include excessive bleeding, risk of infection and CSF leaks and dural fistulas. Infections and leaks can be prevented by giving perioperative antibiotics and identifying and closing of any dural tears. The risk of significant bleeding can be prevented by meticulous technique and blood loss is compensated by transfusions. Blood loss can also be reduced by giving hypotensive anesthesia. Rarely major eye injuries, including blindness, are seen. Visual disturbances can occur due to the eye muscle imbalance after orbital mobilization. Ptosis and diplopia can also occur postoperatively, but this usually self-corrects. A quite difficult problem to correct postoperatively is canthal drift, which can be managed best by carefully preserving the canthal tendon attachments as much as possible. Despite the extensiveness in these procedures, mortality is rarely seen in operative correction of hypertelorism.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 "ocular hypertelorism, orbital hypertelorism". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- ↑ Weinzweig, Jeffrey (2010-04-13). Plastic Surgery Secrets Plus E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-323-08590-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Michael L. Bentz: Pediatric Plastic Surgery; Chapter 9 Hypertelorism by Renato Ocampo, Jr., MD/ John A. Persing, MD

- ↑ Mautner, V (June 2010). "Clinical characterisation of 29 neurofibromatosis type-1 patients with molecularly ascertained 1.4 Mb type-1 NF1 deletions" (PDF). Journal of Medical Genetics. 47 (9): 623–630. doi:10.1136/jmg.2009.075937. PMID 20543202. S2CID 5781561.

- ↑ Donald Serafin, M.D., F.A.C.S. & Nicholas G. Georgiade, D.D.S., M.D., PACS: Pediatric Plastic Surgery Volume I, 1984; Chapter 28 Orbital Hypertelorism by Ian T. Jackson

- ↑ Tessier P, Guiot G, Derome P. Orbital hypertelorism: II. Definite treatment of hypertelorism (OR.H.) by craniofacial or by extracranial osteotomies. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg 7: 39-58, 1973

- ↑ van der Meulen, JC. The pursuit of symmetry in cranio-facial surgery. Br J Plast Surg 29: 84-91, 1976

- ↑ van der Meulen, JC. Medial faciotomy. Br J Plast Surgery 32: 339-342, 1976

- ↑ D Richardson and J K Thiruchelvam: Review Craniofacial surgery for orbital malformations http://www.nature.com/eye/journal/v20/n10/full/6702475a.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hypertelorism. |