Perforated eardrum

| Perforated eardrum | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Perforated tympanic membrane, punctured eardrum, ruptured eardrum | |

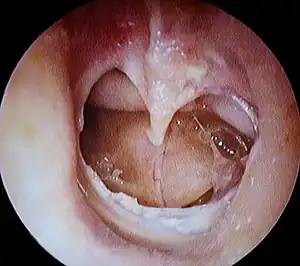

| |

| A completely perforated eardrum, showing the handle of the malleus (hammer bone). | |

| Specialty | ENT surgery |

| Symptoms | Hearing loss, ear pain, ear discharge, ringing in the ear[1] |

| Complications | Long-term hearing loss, cholesteatoma, mastoiditis[2] |

| Usual onset | Sudden[2] |

| Causes | Middle ear infection, physical trauma, overpressure[1][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on examination by otoscopy[1] |

| Treatment | Conservative, antibiotics, surgery[1] |

| Prognosis | Good[2] |

| Frequency | Relatively frequent[2] |

Perforated eardrum, also known as perforated tympanic membrane, is a hole in the eardrum.[1] Symptoms may include hearing loss, ear pain, discharge from the ear, or ringing in the ear.[1] Vertigo may occur, but is typically brief, unless there is an associated inner ear injury.[2][3] Complications may include long-term hearing loss, cholesteatoma, and mastoiditis.[2]

Causes may include a middle ear infection, trauma such as being hit in the ear or ear clearing, a loud noise, or change in pressure, such as seen with scuba diving.[1][3] Diagnosis can be confirmed by looking in the ear with an otoscope.[1] Hearing testing may also be done.[3]

Often a perforations will heal on its own; with recommendations including keeping the ear dry until then.[1][3] If an underlying infection is present, this may be treated with antibiotics.[1] If the hole is large or does not resolve after two month surgery may be an option.[1][3]

Perforated eardrums occur relatively frequently.[2] They most commonly occurs in younger people.[2] Males are more commonly affected than females.[2] Treatment for a perforated eardrum date back to at least the 1640s when plugs were placed in the ears.[4][5]

Signs and symptoms

A perforated eardrum leads to conductive hearing loss, which is usually temporary. Other symptoms may include tinnitus, ear pain, vertigo, or a discharge of mucus.[6] Nausea or vomiting secondary to vertigo may occur.[7]

Causes

A perforated eardrum can have one of many causes, such as:

- Infection (otitis media).[8] This infection may then spread through the middle ear, and may reoccur.[8]

- Trauma. This may be caused by trying to clean ear wax with sharp instrument or cotton swab. It may also occur due to surgical complications.[9]

- Overpressure (loud noise or shockwave from an explosion).

- Flying with a cold, due to changes in air pressure and a blocked Eustachian tubes resulting from the cold.

Diagnosis

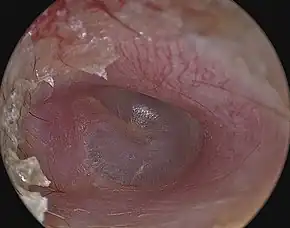

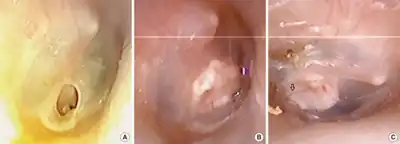

An otoscope can be used to look at the ear canal. This gives a view of the ear canal and eardrum, so that a perforated eardrum can be seen. Tympanometry may also be used.[10]

Treatment

A perforated eardrum often heals on its own.[7][11] This may take a few weeks to few months.[7]

Antibiotics

For those with contaminated wounds, such as those that occurred in water, antibiotic ear drops such as ciprofloxacin may be used.[12]

Surgery

Some perforations require surgical intervention.[8] This may take the form of a paper patch to promote healing (a simple procedure by an ear, nose and throat specialist), or surgery (tympanoplasty).[7] However, in some cases, the perforation can last several years and will be unable to heal naturally. For patients with persistent perforation, surgery is usually undertaken to close the perforation. The objective of the surgery is to provide a platform of sort to support the regrowth and healing of the tympanic membrane in the two weeks post surgery period. There are two ways of doing the surgery:

- Traditional tympanoplasty, usually using the microscope and performed through a 10 cm incision behind the ear lobe. This technique was introduced by Wullstien and Zollner[13] and popularized by the Jim Sheehy at the House Ear Institute.[14]

- Endoscopic tympanoplasty, usually using the endoscope through the ear canal without the need for incision. This technique was introduced and popularized by Professor Tarabichi of TSESI: Tarabichi Stammberger Ear and Sinus Institute.[15]

The success of surgery is variable based on the cause of perforation and the technique being used. Predictors of success include traumatic perforation, dry ear, and central perforations. Predictors of failure includes young age and poor eustachian tube function.[14] The use of minimally invasive endoscopic technique does not reduce the chance of successful outcome.[15] Hearing is usually recovered fully, but chronic infection over a long period may lead to permanent hearing loss. Those with more severe ruptures may need to wear an ear plug to prevent water contact with the ear drum.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Perforated eardrum". nhs.uk. 23 October 2017. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Dolhi, N; Weimer, AD (January 2022). "Tympanic Membrane Perforations". PMID 32491810.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Eardrum Perforation - Ear, Nose, and Throat Disorders". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ↑ Watkinson, John C.; Clarke, Ray W. (12 June 2018). Scott-Brown's Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery: Volume 2: Paediatrics, The Ear, and Skull Base Surgery. CRC Press. p. PT2310. ISBN 978-1-351-39899-2. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ Sarkar, Saurav (28 May 2016). Endoscopic Ear Surgery: A New Horizon. JP Medical Ltd. p. PA53. ISBN 978-93-85891-62-5. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "Perforated eardrum - Symptoms". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ruptured eardrum (perforated eardrum) - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2021-10-03. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- 1 2 3 McGurk, Mark (2006). "12 - ENT Disorders". Essential Human Disease for Dentists. Churchill Livingstone. pp. 195–204. doi:10.1016/B978-0-443-10098-7.50015-4. ISBN 978-0-443-10098-7. Archived from the original on 2021-11-12. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ↑ McCain, Joseph P.; Kim, King (2012). "6 - Endoscopic Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery". Current Therapy In Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Saunders. pp. 31–62. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4160-2527-6.00006-2. ISBN 978-1-4160-2527-6. Archived from the original on 2021-11-12. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ↑ Hain, Timothy C. (2007-01-01), Goetz, Christopher G. (ed.), "Chapter 12 - Cranial Nerve VIII: Vestibulocochlear System", Textbook of Clinical Neurology (Third Edition), Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 199–215, ISBN 978-1-4160-3618-0, archived from the original on 2021-11-12, retrieved 2021-11-12

- ↑ Martin, Lisa (2012). "43 - Chinchillas as Experimental Models". The Laboratory Rabbit, Guinea Pig, Hamster, and Other Rodents. Academic Press, American College of Laboratory Animal Medicine. pp. 1009–1028. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-380920-9.00043-2. ISBN 978-0-12-380920-9. Archived from the original on 2022-04-18. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ↑ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ Zöllner, Fritz (October 1955). "The Principles of Plastic Surgery of the Sound-Conducting Apparatus". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 69 (10): 637–652. doi:10.1017/s0022215100051240. ISSN 0022-2151.

- 1 2 Sheehy, J. L.; Glasscock, M. E. (1967-10-01). "Tympanic Membrane Grafting With Temporalis Fascia". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 86 (4): 391–402. doi:10.1001/archotol.1967.00760050393008. ISSN 0886-4470. PMID 6041111. Archived from the original on 2021-11-02. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- 1 2 Tarabichi, Muaaz; Poe, Dennis S.; Nogueira, João Flávio; Alicandri-Ciufelli, Matteo; Badr-El-Dine, Mohamed; Cohen, Michael S.; Dean, Marc; Isaacson, Brandon; Jufas, Nicholas; Lee, Daniel J.; Leuwer, Rudolf (October 2016). "The Eustachian Tube Redefined". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 49 (5): xvii–xx. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2016.07.013. PMID 27565395. Archived from the original on 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |