Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome

| Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome (PSIS) | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Ectopic neurohypophysis | |

| |

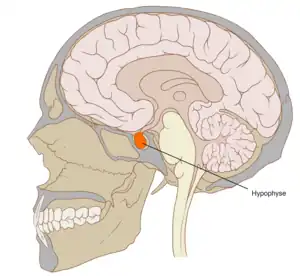

| The location of the pituitary gland within the skull (indicated in orange) | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology, neurology, neonatology, paediatrics |

| Symptoms | Hypoglycaemia, jaudice, micropenis, cryptorchidism, etc. |

| Complications | Seizures, retarded physical and intellectual development, delayed puberty, death, etc. |

| Types | Congenital |

| Risk factors | Genetic predisposition (relative(s) with the condition) |

| Diagnostic method | MRI scan |

| Treatment | Hormone replacement |

| Frequency | Unclear, ~1,000 cases reported |

Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome (PSIS) is a congenital disorder characterised by the triad of an absent or exceedingly thin pituitary stalk, an ectopic or absent posterior pituitary and/or absent or hypoplastic anterior pituitary.[1][2]

Signs and symptoms

Affected individuals may present with hypoglycaemia during the neonatal period, or with growth retardation during childhood (those diagnosed in the neonatal period appear to be affected by a particularly severe form of the disorder). PSIS is a common cause of congenital hypopituitarism, and causes a permanent growth hormone deficit. Some PSIS-affected individuals may also present with adrenal hypoplasia (5-29%), diabetes insipidus (5-29%), primary amenorrhea (5-29%), hypothyroidism (30-79%), failure to thrive (80-99%), septooptic dysplasia (5-29%), and Fanconi anaemia. PSIS may be isolated, or, commonly, present with extra-pituitary malformations.[1][2][3]

PSIS features in neonates (may) include:[1][2][3]

- hypoglycaemia (30-79%)

- (prolonged) jaundice

- micropenis (30-79%)

- cryptorchidism (5-29%)

- delayed intellectual development

- death in infancy (5-29%)

- congenital abnormalities

PSIS features in later childhood (may) include:[1][2][3]

- short stature (80-99%)

- seizures (5-29%)

- hypotension

- delayed intellectual development

- delayed puberty (30-79%)

PSIS is associated with a higher frequency of breech presentation, Caeserian section, and/or low Apgar score, though these are likely consequences rather than causes.[3]

Cause

The cause of the condition is as of yet unknown. Rare genetic mutations may cause familial cases, however, these account for less than 5% of cases.[2]

Diagnosis

Management

Treatment should commence as soon as a diagnosis is established to avoid complications, and consists of hormone replacement, particularly with growth hormone.[1]

Prognosis

Prognosis is generally good in cases of prompt diagnosis and management. Delays may lead to seizures (due to hypoglycaemia), hypotension (due to cortisol deficiency), and/or intellectual disability (due to thyroid endocrine deficits). Due to the before-mentioned factors, mortality and morbidity is higher than that of the general population, particularly during the first 2 years of life.[3]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of PSIS is unknown, however, some 1,000 cases have been reported either with or without the full triad.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2018-08-12. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bar C, Zadro C, Diene G, Oliver I, Pienkowski C, Jouret B, et al. (November 2015). "Pituitary Stalk Interruption Syndrome from Infancy to Adulthood: Clinical, Hormonal, and Radiological Assessment According to the Initial Presentation". PLOS ONE. 10 (11): e0142354. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1042354B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142354. PMC 4643020. PMID 26562670.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brauner R. "Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome". Orphanet. Archived from the original on 2018-08-12. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

External links

| External resources |

|

|---|