Red nucleus

| Red nucleus | |

|---|---|

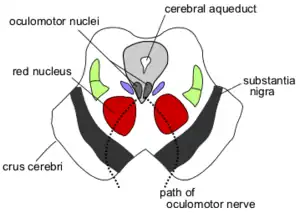

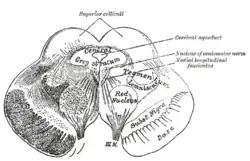

Transverse section through the midbrain showing the location of the red nuclei. The superior colliculi are at the top of image and the cerebral peduncles at the bottom of image – both in section. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Midbrain |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nucleus ruber |

| MeSH | D012012 |

| NeuroNames | 505 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1478 |

| TA98 | A14.1.06.323 |

| TA2 | 5898 |

| FMA | 62407 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The red nucleus or nucleus ruber is a structure in the rostral midbrain involved in motor coordination.[1] The red nucleus is pale pink, which is believed to be due to the presence of iron in at least two different forms: hemoglobin and ferritin.[2][3] The structure is located in the tegmentum of the midbrain next to the substantia nigra and comprises caudal magnocellular and rostral parvocellular components.[1] The red nucleus and substantia nigra are subcortical centers of the extrapyramidal motor system.

Function

In a vertebrate without a significant corticospinal tract, gait is mainly controlled by the red nucleus.[4] However, in primates, where the corticospinal tract is dominant, the rubrospinal tract may be regarded as vestigial in motor function. Therefore, the red nucleus is less important in primates than in many other mammals.[1][5] Nevertheless, the crawling of babies is controlled by the red nucleus, as is arm swinging in typical walking.[6] The red nucleus may play an additional role in controlling muscles of the shoulder and upper arm via projections of its magnocellular part.[7][8] In humans, the red nucleus also has limited control over hands, as the rubrospinal tract is more involved in large muscle movement such as that for the arms (but not for the legs, as the tract terminates in the superior thoracic region of the spinal cord). Fine control of the fingers is not modified by the functioning of the red nucleus but relies on the corticospinal tract.[9] The majority of red nucleus axons do not project to the spinal cord but, via its parvocellular part, relay information from the motor cortex to the cerebellum through the inferior olivary complex, an important relay center in the medulla.[1]

Input and output

The red nucleus receives many inputs from the cerebellum (interposed nucleus and the lateral cerebellar nucleus) of the opposite side and an input from the motor cortex of the same side.[10]

The red nucleus has two sets of efferents:[10]

- In humans, the majority of the output goes to the bundle of fibers continues through the medial tegmental field toward the inferior olive of the same side, to form part of a pathway that ultimately influence the cerebellum.

- The other output (the rubrospinal projection) goes to the rhombencephalic reticular formation and spinal cord of the opposite side, making up the rubrospinal tract, which runs ventral to the lateral corticospinal tract. As stated earlier, the rubrospinal tract is more important in non-primate species: in primates, because of the well-developed cerebral cortex, the corticospinal tract has taken over the role of the rubrospinal.

See also

Additional images

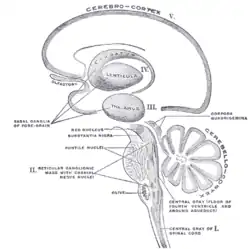

Schematic representation of the chief ganglionic categories (I to V).

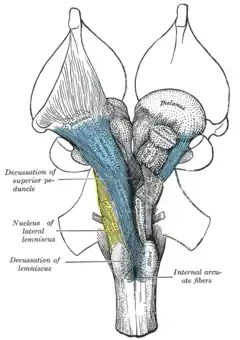

Schematic representation of the chief ganglionic categories (I to V). Deep dissection of brain-stem. Ventral view.

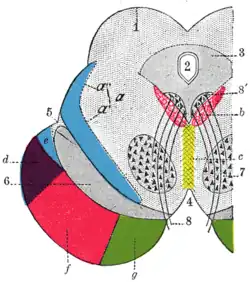

Deep dissection of brain-stem. Ventral view. Transverse section through mid-brain.

Transverse section through mid-brain. Transverse section of mid-brain at level of superior colliculi.

Transverse section of mid-brain at level of superior colliculi. Coronal section of brain immediately in front of pons.

Coronal section of brain immediately in front of pons._section_description_2.JPG.webp) Human brain frontal (coronal) section

Human brain frontal (coronal) section

Red nucleus

Red nucleus Cerebral peduncle, optic chasm, cerebral aqueduct. Inferior view. Deep dissection.

Cerebral peduncle, optic chasm, cerebral aqueduct. Inferior view. Deep dissection. Cerebrum. Inferior view.Deep dissection

Cerebrum. Inferior view.Deep dissection

References

- 1 2 3 4 Cacciola, Alberto; Milardi, Demetrio; Basile, Gianpaolo Antonio; Bertino, Salvatore; Calamuneri, Alessandro; Chillemi, Gaetana; Paladina, Giuseppe; Impellizzeri, Federica; Trimarchi, Fabio; Anastasi, Giuseppe; Bramanti, Alessia; Rizzo, Giuseppina (2019-08-20). "The cortico-rubral and cerebello-rubral pathways are topographically organized within the human red nucleus". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 12117. Bibcode:2019NatSR...912117C. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-48164-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6702172. PMID 31431648.

- ↑ Wikipedia Red Nucleus Revision https://sites.google.com/site/childrenoftheamphioxus/table-of-contents/wikipedia-red-nucleus-revision

- ↑ Drayer, B.; Burger, P.; Darwin, R.; Riederer, S.; Herfkens, R.; Johnson, G. A. (July 1986). "MRI of brain iron". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 147 (1): 103–110. doi:10.2214/ajr.147.1.103. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 3487201.

- ↑ ten Donkelaar, H. J. (1988-04-01). "Evolution of the red nucleus and rubrospinal tract". Behavioural Brain Research. 28 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1016/0166-4328(88)90072-1. ISSN 0166-4328. PMID 3289562. S2CID 54367413.

- ↑ Onodera, Satoru; Hicks, T. Philip (2009-08-13). "A Comparative Neuroanatomical Study of the Red Nucleus of the Cat, Macaque and Human". PLOS ONE. 4 (8): –6623. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.6623O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006623. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2722087. PMID 19675676. S2CID 18760268.

- ↑ Being and Perceiving. Manupod Press. 2011. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-9569621-0-2.

- ↑ Gibson, A. R.; Houk, J. C.; Kohlerman, N. J. (1985). "Magnocellular red nucleus activity during different types of limb movement in the macaque monkey". The Journal of Physiology. 358 (1): 527–549. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015565. ISSN 1469-7793. PMC 1193356. PMID 3981472.

- ↑ van Kan, Peter L.; McCurdy, Martha L. (2002-01-01). "Discharge of primate magnocellular red nucleus neurons during reaching to grasp in different spatial locations". Experimental Brain Research. 142 (1): 151–157. doi:10.1007/s00221-001-0924-5. ISSN 1432-1106. PMID 11797092. S2CID 42113292.

- ↑ Bunday, Karen L.; Tazoe, Toshiki; Rothwell, John C.; Perez, Monica A. (2014-05-21). "Subcortical Control of Precision Grip after Human Spinal Cord Injury". Journal of Neuroscience. 34 (21): 7341–7350. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0390-14.2014. ISSN 1529-2401. PMC 4028504. PMID 24849366.

- 1 2 Milardi, Demetrio; Cacciola, Alberto; Cutroneo, Giuseppina; Marino, Silvia; Irrera, Mariangela; Cacciola, Giorgio; Santoro, Giuseppe; Ciolli, Pietro; Anastasi, Giuseppe; Calabrò, Rocco Salvatore; Quartarone, Angelo (2016-07-28). "Red nucleus connectivity as revealed by constrained spherical deconvolution tractography". Neuroscience Letters. 626: 68–73. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2016.05.009. ISSN 0304-3940. PMID 27181514. S2CID 46756208. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Red nucleus. |