Vestibulospinal tract

| Vestibulospinal tract | |

|---|---|

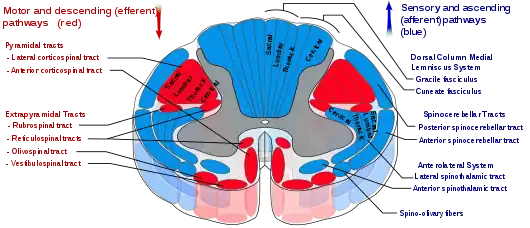

Vestibulospinal tract is labeled, in red at bottom left. | |

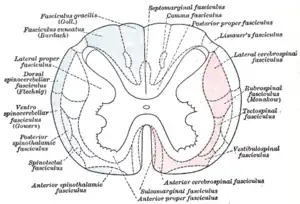

Diagram of the principal fasciculi of the spinal cord. (Vestibulospinal fasciculus labeled at bottom right.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tractus vestibulospinalis |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1643 |

| FMA | 72646 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The vestibulospinal tract is a neural tract in the central nervous system. Specifically, it is a component of the extrapyramidal system and is classified as a component of the medial pathway. Like other descending motor pathways, the vestibulospinal fibers of the tract relay information from nuclei to motor neurons.[1] The vestibular nuclei receive information through the vestibulocochlear nerve about changes in the orientation of the head. The nuclei relay motor commands through the vestibulospinal tract. The function of these motor commands is to alter muscle tone, extend, and change the position of the limbs and head with the goal of supporting posture and maintaining balance of the body and head.[1]

Classification

The vestibulospinal tract is part of the "extrapyramidal system" of the central nervous system. In human anatomy, the extrapyramidal system is a neural network located in the brain that is part of the motor system involved in the coordination of movement.[2] The system is called "extrapyramidal" to distinguish it from the tracts of the motor cortex that reach their targets by traveling through the "pyramids" of the medulla. The pyramidal pathways, such as corticospinal and some corticobulbar tracts, may directly innervate motor neurons of the spinal cord or brainstem. This is seen in anterior (ventral) horn cells or certain cranial nerve nuclei. Whereas the extrapyramidal system centers around the modulation and regulation through indirect control of anterior (ventral) horn cells. The extrapyramidal subcortical nuclei include the substantia nigra, caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, thalamus, red nucleus and subthalamic nucleus.[3]

The traditional thought was that the extrapyramidal system operated entirely independently of the pyramidal system. However, more recent research has provided a greater understanding of the integration of motor control. Motor control from both the pyramidal and extrapyramidal systems have extensive feedback loops and are heavily interconnected with each other.[1] A more appropriate classification of motor nuclei and tracts would be by their functions. When broken down by function there are two major pathways: medial and lateral. The medial pathway helps control gross movements of the proximal limbs and trunk. The lateral pathway helps control precise movement of the distal portion of limbs.[1] The vestibulospinal tract, as well as tectospinal and reticulospinal tracts are examples of components of the medial pathway.[1]

Function

The vestibulospinal tract is part of the vestibular system in the CNS. The primary role of the vestibular system is to maintain head and eye coordination, upright posture and balance, and conscious realization of spatial orientation and motion. The vestibular system is able to respond correctly by recording sensory information from hairs cells in the labyrinth of the inner ear. Then the nuclei receiving these signals project out to the extraocular muscles, spinal cord, and cerebral cortex to execute these functions.[4]

One of these projections, the vestibulospinal tract, is responsible for upright posture and head stabilization. When the vestibular sensory neurons detect small movements of the body, the vestibulospinal tract commands motor signals to specific muscles to counteract these movements and re-stabilize the body.

The vestibulospinal tract is an upper motor neuron tract consisting of two sub-pathways:

- The medial vestibulospinal tract projects bilaterally from the medial vestibular nucleus within the medial longitudinal fasciculus to the ventral horns in the upper cervical cord (C6 vertebra).[5] It promotes stabilization of head position by innervating the neck muscles, which helps with head coordination and eye movement. Its function is similar to that of the tectospinal tract.

- The lateral vestibulospinal tract provides excitatory signals to interneurons, which relay the signal to the motor neurons in antigravity muscles.[6] These antigravity muscles are extensor muscles in the legs that help maintain upright and balanced posture.

Anatomy

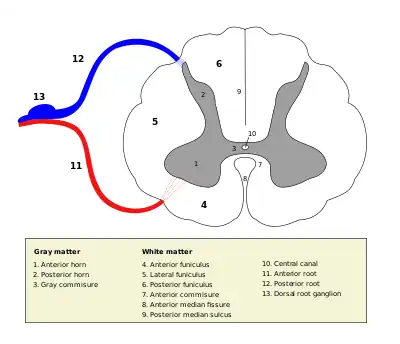

| Spinal cord | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | medulla spinalis |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1643 |

| FMA | 72646 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Lateral vestibulospinal tract

The lateral vestibulospinal tract is a group of descending extrapyramidal motor neurons, or efferent nerve fibers.[2] This tract is found in the lateral funiculus, a bundle of nerve roots in the spinal cord. The lateral vestibulospinal tract originates in the lateral vestibular nucleus or Deiters’ nucleus in the pons.[2] The Deiters' nucleus extends from pontomedullary junction to the level of abducens nerve nucleus in the pons.[2]

Lateral vestibulospinal fibers descend uncrossed, or ipsilateral, in the anterior portion of the lateral funiculus of the spinal cord.[2][7] Fibers run down the total length of the spinal cord and terminate at the interneurons of laminae VII and VIII. Additionally, some neurons terminate directly on the dendrites of alpha motor neurons in the same laminae.[2]

Medial vestibulospinal tract

The medial vestibulospinal tract is a group of descending extrapyramidal motor neurons, or efferent fibers found in the anterior funiculus, a bundle of nerve roots in the spinal cord. The medial vestibulospinal tract originates in the medial vestibular nucleus or Schwalbe's nucleus.[2] The Schwalbe's nucleus extends from the rostral end of the inferior olivary nucleus of the medulla oblongata to the caudal portion of the pons.[2]

Medial vestibulospinal fibers join with the ipsilateral and contralateral medial longitudinal fasciculus, and descend in the anterior funiculus of the spinal cord.[2][7] Fibers run down to the anterior funiculus to the cervical spinal cord segments and terminate on neurons of laminae VII and VIII. Unlike the lateral vestibulospinal tract, the medial vestibulospinal tract innervates muscles that support the head. As a result, medial vestibulospinal fibers run down only to the cervical segments of the cord.[2]

Reflexes

The vestibulospinal reflex uses the vestibular organs as well as skeletal muscle in order to maintain balance, posture, and stability in an environment with gravity. These reflexes can be further broken down by timing into a dynamic reflex, static reflex or tonic reflex. It can also be categorized by the sensory input as either canals, otolith, or both. The term vestibulospinal reflex, is most commonly used when the sensory input evokes a response from the muscular system below the neck. These reflexes are important in the maintenance of homeostasis.[8]

Example of vestibulospinal reflex

- The head is tilted to one side which stimulates both the canals and the otoliths.

- This movement stimulates the vestibular nerve as well as the vestibular nucleus.

- These impulses are transmitted down both the lateral and medial vestibulospinal tracts to the spinal cord.

- The spinal cord induces extensor effects in the muscle on the side of the neck to which the head is bent, and flexor effects in the muscle in the side of the neck away from the direction of the displaced head.

Tonic labyrinthine reflex

The tonic labyrinthine reflex (TLR) is a reflex that is present in newborn babies directly after birth and should be fully inhibited by 3.5 years.[9] This reflex helps the baby master head and neck movements outside of the womb as well as the concept of gravity. Increased muscle tone, development of the proprioceptive and vestibular senses and opportunities to practice with balance are all consequences of this reflex. During early childhood, the TLR matures into more developed vestibulospinal reflexes to help with posture, head alignment and balance.[10]

The tonic labyrinthine reflex is found in two forms.

- Forward: When the head bends forward, the whole body, arms, legs and torso curl together to form the fetal position.

- Backwards: When the head is bent backward, the whole body, arms, legs and torso straighten and extend.

Righting reflex

The righting reflex is another type of reflex. This reflex positions the head or body back into its "normal" position, in response to a change in head or body position. A common example of this reflex is the cat righting reflex, which allows them to orient themselves in order to land on their feet. This reflex is initiated by sensory information from the vestibular, visual, and the somatosensory systems and is therefore not only a vestibulospinal reflex.[8]

Damage

A typical person sways from side to side when the eyes are closed. This is the result of the vestibulospinal reflex working correctly. When an individual sways to the left side, the left lateral vestibulospinal tract is activated to bring the body back to midline.[7] Generally damage to the vestibulospinal system results in ataxia and postural instability.[11] For example, if unilateral damage occurs to the vestibulocochlear nerve, lateral vestibular nucleus, semicircular canals or lateral vestibulospinal tract, the person will likely sway to that side and fall when walking. This occurs because the healthy side "over powers" the weak side in a way that will cause the person to veer and fall towards the injured side.[6] Potential early onset of damage can be witnessed through a positive Romberg's test.[6] Patients with bilateral or unilateral vestibular system damage will likely regain postural stability over weeks and months through a process called vestibular compensation.[11] This process is likely related to a greater reliance on other sensory information.

Current and future research

- Recent research has shown that damage to the medial vestibulospinal tract alters vestibular evoked myogenic potential in the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM),[12][13] which are involved in head rotation. The vestibular evoked myogenic potential is an assessment of the sacculo-collic reflex and a test of function in otolithic organs. Also, lesions to the tract impair ascending efferent fiber signaling, which led to nystagmus.[12][13]

- There has also been recent research to determine if there is a difference in vestibulospinal function when there is damage to the superior vestibular nerve as opposed to the inferior vestibular nerve and vice versa. They defined vestibulospinal function by ability to have proper posture, as well as by self reported dizziness. The results were determined by using the Sensory Organization Test (SOT) of the computerized dynamic posturography (CDP) as well as the dizziness handicap inventory (DHI). It was determined that subjects with damaged inferior spinal nerve performed worse on the posture test than the control group, but performed better than patients with superior vestibulo nerve damage. With this they determined that the superior vestibular nerve plays a larger role in balance than the inferior vestibulo nerve but that they both play a role. In terms of the DHI it was concluded that there was no difference between the patients with the two different impairments.[14]

- Vestibular compensation after unilateral or bilateral vestibular system damage can be accomplished by sensory addition and sensory substitution. Sensory substitution occurs when any remaining vestibular function, vision, or light touch of a stable surface substitute for the lost function. Postural sway and gait ataxia can be reduced by augmenting sensory information for balance control. Recent research has shown that as little as 100 grams of light touch of a fingertip can provide enough sensory reference to reduce sway and ataxia during gait.[11]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Martini, Frederic (2010). Anatomy & Physiology. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-321-59713-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Afifi, Adel (1998). Functional Neuroanatomy. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-001589-0.

- ↑ "Motor Systems". Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ↑ Voron, Stephen. "The Vestibular System". University of Utah School of Medicine. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ Miselis, Dr. Richard. "Laboratory 12 : Tract Systems I". University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 "VESTIBULAR NUCLEI AND ABDUCENS NUCLEUS". Medical Neurosciences University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on November 9, 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 Bono, Christopher (2010). Spinal Cord Medicine. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-933864-19-8.

- 1 2 Hain, Timothy. "Postural, Vestibulospinal and Vestibulocollic Reflexes". Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ "Primitive Reflexes and How They Effect Performance". Brain and Behaviour Enhancement. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ Story, Sonia. "TLR: Tonic Labyrinthine Reflex". Brain Development Through Movement and Play. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 Horak, Fay (May 2009). "Postural Compensation for Vestibular Loss". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1164 (1): 76–81. Bibcode:2009NYASA1164...76H. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03708.x. PMC 3224857. PMID 19645883.

- 1 2 Kim, Seonhye; Lee, Hak-Seung; Kim, Ji Soo (7 January 2010). "Medial vestibulospinal tract lesions impair sacculo-collic reflexes". Journal of Neurology. 257 (5): 825–832. doi:10.1007/s00415-009-5427-5. PMID 20054695. S2CID 20645277.

- 1 2 Kim, Seonhye; Kim, Hyo-Jung; Kim, Ji Soo (1 January 2011). "Impaired Sacculocollic Reflex in Lateral Medullary Infarction". Frontiers in Neurology. 2: 8. doi:10.3389/fneur.2011.00008. PMC 3041465. PMID 21415908.

- ↑ McCaslin, DL (September 2011). "The influence of unilateral saccular impairment on functional balance performance and self-report dizziness". Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 22 (8): 542–549. doi:10.3766/jaaa.22.8.6. PMID 22031678.