This article was co-authored by Lucy V. Hay. Lucy V. Hay is an author, script editor and blogger who helps other writers through writing workshops, courses, and her blog Bang2Write. Lucy is the producer of two British thrillers and her debut crime novel, The Other Twin, is currently being adapted for the screen by Free@Last TV, makers of the Emmy-nominated Agatha Raisin.

There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, 87% of readers who voted found the article helpful, earning it our reader-approved status.

This article has been viewed 41,186 times.

It's really surprising how many novels have clichéd, stereotyped female characters. One would think writers would know how to avoid these poor characterizations nowadays, when it's been done a thousand times already. Writing female characters that have no purpose or personality quickly becomes annoying, both for the writer and for the reader. Learning how to avoid female stereotypes and clichés will strengthen your writing and make your work more enjoyable to read.

Steps

Writing Women Well

-

1Write several important female characters. There is no right way to be a woman, and the more women you have in the story, the more clearly your story will convey this. Give your women different roles, different personalities, and different skills. Diverse female characters will help you avoid stale tropes.

- If you are writing a story for a mixed-gender audience, your cast should be about 50% female, and the women should get about equal screen time.

- If you only have one major female character, you may be tempted to make her hyper-competent, to show that you believe women can be capable too. This may make her feel unrealistic. It's better to have several women, with diverse skill sets, instead of having a single walking talking Swiss Army knife of a female character.

-

2Have her help solve problems. Give her a clear set of skills, and let her actions meaningfully contribute to the plot. Her actions should move the story along. What decisions does she make? What are her talents, and how can she use them to help?

- Give a leading lady an active role throughout the story, not just one or two moments of usefulness.

Advertisement -

3Make sure she wants something. What is her motivation? Giving your leading ladies something to strive for helps them become more nuanced, interesting characters. Give each of them a goal beyond helping the team or finding a boyfriend, and they will become more exciting in the readers' eyes.

- She wants to prove herself and make a meaningful contribution to her field.

- She wants a friend.

- She wants to cure the disease that killed her mother.

- She wants to win a competition.

- She really, really longs for a pet cat.

-

4Show how she struggles. If she's on top of things all the time, her story won't be nearly as deep as it could be. What hardships does she face in life? What are her fears? Delve into the difficulties she experiences, just like you would for characters who aren't female.

- Some writers jump to "female" issues, like pregnancy or abusive men. But women experience more than this in their daily lives. Consider family troubles, school/career problems, health issues, relationship troubles, and other areas to explore.

-

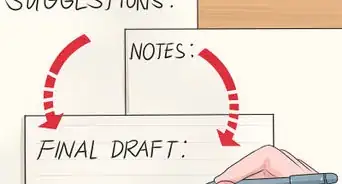

5Give your leading lady some meaningful character development. Show that she has vulnerability as well as strength, and let her learn and grow along the way. This will help you create a complex, relatable character. Here are some examples:

- She learns to step up, let her voice be heard, and be a leader.

- She learns to relax and take life a little more slowly.

- She learns to ask for help in coping with her PTSD from her difficult past.

- She stops looking down on people who aren't as smart as her.

- She figures out what she wants in life.

-

6Break narrow gender roles. Show your audience that women can succeed in STEM, that they can be leaders, that they can be successful at work while having kids. This will inspire your female readers, and send a positive social message that will create a little extra buzz about your book.

- Show that it's okay to wear skirts or dresses, and success doesn't mean becoming more masculine. A woman can still be traditionally feminine (dressing girly, liking pop music, dating) while being successful and awesome.

- Don't let femininity be seen as degrading. Don't have your heroic men (or women) express disgust at pink, girly things, or being placed in a role that is usually reserved for women. Or if they do, show how this is wrong.

- While showing women who succeed in STEM is great, succeeding in STEM isn't the only way to be successful or strong. Show women that are successful in other areas such as the arts, music, or literature.

-

7Give her meaningful relationships beyond romance. Build her relationship with her sister, her coach, or her platonic male friend. Show how she interacts with others. Let readers see how she reacts to their vulnerability, and how they react to hers. Show them bantering, working, and just being silly. This will help her become likable in the readers' eyes.[1]

-

8Write more than one or two women. Some stories make the mistake of having a female main character or two, and having the rest of the world populated by men. You can avoid this pitfall by making some minor characters female. There is the absentminded mother, the stern councilwoman, the comic relief shopkeeper, the bored bank teller... Let women also occupy some of the minor roles in your story, and this will help show that there are many kinds of women.

-

9Create diversity in other forms. Write women of different races, disabilities, sizes, religions, sexualities, appearances, et cetera. This will help you reach out to groups that are often underrepresented in the media, and promote a positive message.

- Many curly-haired women and/or women of color like to see curly-haired female characters and/or female characters of color.

- Disability is more than wheelchairs and white canes. Also consider Deaf women, chronically anxious women, autistic women, women with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder...

Avoiding Specific Stereotypes

-

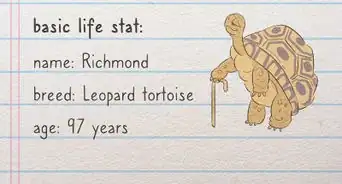

1Recognize the pitfalls of a Mary Sue. Mary Sues are the author's favorite character, and they get preferential treatment (e.g. most beautiful, gets to break rules, overpowered). This is irritating to readers because the author's love of the character is being pushed down their throat. Make sure your character is balanced, and not unrealistically more talented than her peers.[2]

- Mary Sues can also be male. Male Mary Sue characters are sometimes called Gary Stus or Marty Sues.

- Mary Sues tend to have many things handed to them (e.g. incredible inborn magical talent, super duper rich) but may have tragic backstories to show how far they've come.

- Attention is often called to the Mary Sue, sometimes at the expense of the plot. When she falls, the whole world rushes to her aid.

- Many beginning writers create Mary Sues, so don't feel bad if you discover that you have one. It's very normal, and you can revisit the character to grow them beyond their current characterization.

Tip: Being a "Mary Sue" isn't about basic details like eye color or sad backstories. It's about how the story treats the character. Over-the-top attempts to give them attention, sympathy, or respect might be a sign of uneven writing.[3]

-

2Avoid Anti-Sues as well. An Anti-Sue is a reaction to the Mary Sue phenomenon, when the writer responds by writing a weak character. The story goes to great lengths to make sure the reader know that the character is ugly/plain, clumsy, uninteresting, traumatized, et cetera. The writer has forgotten that it's okay to make a strong and powerful woman.

- The character may be constantly falling down, tripping, hurting themselves and bumping into everything and everyone just to show oh-how-awkward the character is.

- Often, these characters keep repeatedly thinking how common and boring they are compared to other people, noticeably their romantic interest, and how said romantic interest "could have literally anyone else but chose me!" This can become painful to read. Bella Swan from Twilight is sometimes cited as an example.

- Anti Sues tend to be female, because usually Mary Sue accusations are leveled at female characters.

-

3Avoid hurtful stereotypes related to gender, race, size, disability, et cetera. Spend a bit of time researching these traits, and reading what people with these traits have to say about how they are represented in fiction. For example, if you're writing a black autistic girl, read what black women and autistic women have to say. This will help you craft an appealing, non-insulting character. Here are general stereotypes to avoid:

- The sassy black woman, the Indian doctor/call center worker, the spicy Latina, the genius Asian girl, the Native American who is extremely connected to nature, and other racial stereotypes

- The fat, lazy couch potato

- The welfare queen

- The man-hating lesbian, the confused bisexual woman, the asexual woman who "just needs to get laid," the transgender woman whose existence is a joke to be made fun of, the LGBT+ character who gets killed off

- The violent/dangerous mentally ill woman

- The disabled woman who ends up cured or dead, or is just a burden on others

- The greedy or hypercritical Jewish woman, the terrorist or victimized Muslim woman, and other religious stereotypes

EXPERT TIPLucy V. Hay is an author, script editor and blogger who helps other writers through writing workshops, courses, and her blog Bang2Write. Lucy is the producer of two British thrillers and her debut crime novel, The Other Twin, is currently being adapted for the screen by Free@Last TV, makers of the Emmy-nominated Agatha Raisin.Professional Writer

Lucy V. Hay

Lucy V. Hay

Professional WriterStereotypes don't have to be related to a character's physical characteristics. Screenwriter and script editor Lucy Hay says: "We often see stereotypes of sad, doomed characters, like teenager mothers who are irresponsible and ill-educated. They may date drug dealers, for instance, or they may not look after their children properly. A character who subverts that trend would be someone like Juno—she doesn't want to have a baby or get an abortion, so she decides to do the grown-up thing and find a good parent for her child."

-

4Make sure that your strong female character is actually strong. Sometimes writers will succumb to the Trinity Effect, where a woman will have an introduction showing how awesome she is, only to be eclipsed and ultimately need rescue from a man.[4] The reader is informed that she is capable, but she relies on the male hero in the end.[5] Ask yourself if she makes meaningful contributions throughout the plot, and if the bumbling hero learns much faster than she does. Would you, the writer, want to be her?

- This may happen by relegating her to the less exciting B-fight during the climax,[6] or having her face the major villain first but get defeated and need the man to save her. She may even be "fridged," or horribly maimed/killed to motivate the male character(s) to stop the villain.

-

5Avoid the "Damsel in Distress". Another overdone trope, a "Damsel in Distress" is essentially a female character who is only there to be rescued by the hero and does nothing to help anyone, nor adds anything to the story. This type of character literally stands there, waiting to be rescued (and often screaming or acting helpless) and does nothing else. Or, she may try and fail to escape, but need a man to save her.

- This does not mean to never place women in distress. It is okay for one of them to need help, especially if women occupy strong and active roles throughout your book.

- One way to invert this could be to place a strong woman in distress, only for her to save herself, and perhaps her would-be rescue party as well. Or let a woman save another woman.

- Or let a man be in distress for a change, so the woman can save him. Men are allowed to need help from women too.

-

6Avoid the "woman in refrigerator" at all costs. This is most commonly seen in superhero media, but that doesn't mean it can't infect other types of media too. The hero meets a cute, capable, likable woman whose character is developed so the reader can like her too. Then the hero finds her maimed or dead.[7] No one likes characters who are used as plot devices/props for destroying the hero's psyche or motivating him to action.

- They may be murdered, raped, disfigured, beaten up, or forced to suffer through overall horrifying things just so the hero can be sad.[8]

- This may happen to the hero's romantic interest, a family member, or even someone he doesn't know well. They don't even have to be developed (Debbie from Savage Dragon) or be introduced before something bad happens to them (Mal from Inception) to be used as a way to emotionally scar the hero.

Tip: A character is "fridged" if the thing that happens to her permanently places her in the victim role. But not if she makes a comeback. For example, if she's in a wheelchair and the story only references her as a tragic victim after this, then she's fridged. But if she rolls up in her wheelchair ready to kick butt and stop the villain, then she's awesome, not fridged.

-

7Make your writing show the reality that women have other interests in life besides men. Consider how often the story passes the Bechdel Test. This test evaluates if you (1) have two named female characters, who (2) talk to each other at some point (3) about something other than men.[9] This is a quick way to evaluate whether your story treats female characters as plot devices/props.

- In a perfectly mixed-gender story, about 25% of the conversations would be between women, 50% would be between a woman and a man, and 25% would be between men.

- In a story for predominantly male audiences, there may be fewer conversations that pass the Bechdel Test. (Be aware that women do read "men's books!" And men can like and relate to female characters too.)

-

8Be aware that your female character doesn't need to date a man. So many stories assign female characters designated men to end up with. This can be annoying to readers in general, especially if it feels forced. Try letting some of your ladies be single at the end (since fulfillment does not require romance), or having them date another woman. Show readers that women don't need men to be happy.

- Avoid going to great leaps just to pair up your leading lady; this usually doesn't go over very well. If it seems like it might feel forced, then don't give her someone to date. Let her stay happy and single.

- Happiness is not always a man. Happiness could be a good career, a happy family life, or a dog that gets very excited when she comes home from work each day.

- If your cast is more male, and you want them to be paired up, try making some of them gay or bisexual. Remember, men don't need women to be happy either.

-

9Show women supporting each other instead of tearing each other down. Sometimes (both in fiction and real life) women feel that they need to compete with each other, and tear each other down in order to look better to men. This is obviously not constructive, and it can become tiresome to readers when it happens too often. Show women who build each other up and support each other when they stumble. They will be excellent role models, and your reader will walk away with a smile.

Community Q&A

-

QuestionI'm writing a book about a girl who can "jump" into books. She is colored, headstrong, smart, capable, and distant. Anything but trendy. But I feel like I'm missing something.

PamelaCommunity AnswerYou're missing flaws. Don't write a Mary-Sue. Even the strongest characters have weaknesses. In Lord of the Rings, Boromir had the want of the One Ring as his flaw. In Star Wars, Anakin's flaw was pride. In Harry Potter, Ron's flaw was jealousy.

PamelaCommunity AnswerYou're missing flaws. Don't write a Mary-Sue. Even the strongest characters have weaknesses. In Lord of the Rings, Boromir had the want of the One Ring as his flaw. In Star Wars, Anakin's flaw was pride. In Harry Potter, Ron's flaw was jealousy. -

QuestionI've decided to make one of the 'mean girls' in my book Islamic. How do I do that without starting or contributing to stereotypes?

Community AnswerIslamic girls of all personalities exist. You could add another mean girl or nice Islamic character to balance it out, but I think a better choice would be keeping the girl's "mean" characteristics separate from her religion. Don't make her someone who lashes out at other people because of her religious beliefs or you risk demonizing all Islamic people.

Community AnswerIslamic girls of all personalities exist. You could add another mean girl or nice Islamic character to balance it out, but I think a better choice would be keeping the girl's "mean" characteristics separate from her religion. Don't make her someone who lashes out at other people because of her religious beliefs or you risk demonizing all Islamic people. -

QuestionIs it bad to make a boy crazy girl? I want my book to be cliche in a fun way.

Community AnswerSure, that's fine. Just try to give her other personality traits besides being boy crazy, like she could be really smart or creative, or a really friendly person. You don't want your characters to be one-dimensional.

Community AnswerSure, that's fine. Just try to give her other personality traits besides being boy crazy, like she could be really smart or creative, or a really friendly person. You don't want your characters to be one-dimensional.

References

- ↑ https://misslunarose.home.blog/2019/05/24/why-readers-like-glitter/

- ↑ "Help! I Have a Mary Sue!"

- ↑ https://misslunarose.home.blog/2020/04/25/mary-sue-test/

- ↑ Tasha Robinson: We're losing all our Strong Female Characters to Trinity Syndrome

- ↑ TV Tropes: Faux Action Girl

- ↑ Robot Hugs: Pitch

- ↑ TV Tropes: Stuffed into the Fridge

- ↑ Women in Refrigerators (official website by Gail Simone)

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bechdel_test