wikiHow is a “wiki,” similar to Wikipedia, which means that many of our articles are co-written by multiple authors. To create this article, 33 people, some anonymous, worked to edit and improve it over time.

There are 27 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, 89% of readers who voted found the article helpful, earning it our reader-approved status.

This article has been viewed 70,438 times.

Learn more...

In the writing world, characters are often straight and cisgender, which typically means they never face struggles with their gender identity or sexuality. However, there are a lot of people who don't fit this stereotype. Writing an LGBTQ+ character who has a different gender identity or sexuality than you do might seem overwhelming, but it’s a lot easier than it may seem. In this article, we’ll walk you through the process so that you can craft characters who come off as authentic, empathetic representations.

Steps

Writing Well

-

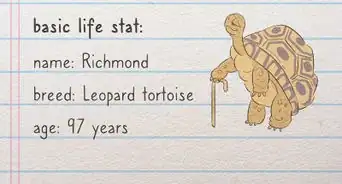

1Design a character, not just "a lesbian" or "a trans boy." Before deciding on your character's sexuality, gender identity, and relationship status, you'll need to decide on the basics of your character. What's their name and how old are they? What do they look like? What's their role in the story? Keep in mind that your character defines their identity—the identity doesn't define them.[1]

- Your character should have a personality and backstory that is just as nuanced as those of the straight and cis characters.

-

2Read from the community you wish to represent. What are their lives like? What are their struggles, their goals, the things they are grateful for? Which characters do they say are done well, and why? Which stereotypes and/or tropes do they hate? What advice do they have for you? If you take time to listen to the community, you will understand them better.

- Try sending out a message asking for advice on social media. You may get some great tips!

- If you don't feel comfortable asking LGBT+ people about their experiences, look for LGBT+ public figures who have shared their stories.[2]

Advertisement -

3Carefully consider your character's development arc. What lesson do they learn? What is their major flaw, and how do they overcome it (if at all)? If they are the main character, facing this problem head-on will mark the climax of the story. This may or may not be related to their identity. For example:

- Lane suffered bullying in childhood, and their dad died in a traumatic car accident. They are afraid to open up to anyone. With the help of their boyfriend, they begin sharing more. The climax is when they finally agree to sing karaoke at a party, only to forget the lyrics. Lane learns that failure is okay, and people can be more forgiving than they know.

- Dijon lives life according to social norms, working hard and studying medicine like his mom wants. He slowly learns to listen to his own desires, and accepting himself as asexual is part of this. The climax is when he announces to his mother that he is going to the state university to study engineering, not medical school, because this is what he wants.

- Bayta is trans and bisexual, but this isn't very important to the story. Her character arc is about accepting herself as autistic and learning to ask for help.

Tip: While self-acceptance, coming out, and transition are common plotlines for LGBT+ characters, their story doesn't need to revolve around these things.[3] Many LGBT+ readers enjoy seeing characters who are secure in their identity and are doing things unrelated to it.

-

4Map out your character's strengths and weaknesses. Well-rounded characters, like real people, have a mix of positive and negative traits that influence how they behave and how they drive the plot.

- What are they good at? What positive contributions will they make to the plot? How do they help others? Give your character some real strong points, and readers will be reminded that LGBT+ people are talented and worth having around.

- What does your character struggle with? What flaws can potentially undermine their efforts, and how does it impact the plot? When do they need to ask for help? (These do not need to be related to their identity.) Flaws humanize a character, and can show their development and weak spots.

-

5Remember the diversity of people under the LGBT+ umbrella. Everyone is unique, and different people will have different experiences. Tailor your character's past and present to the demands of their story and their personality. There are thousands of ways to be bisexual, gay or transgender, and none of them are bad or wrong.

- Every identity under the umbrella has its own unique experiences. Gay people have different experiences than bisexual people, who have different experiences from nonbinary people, and so on.

- Consider intersectionality as well. There are LGBT+ people of all ages who are people of color, disabled, overweight, of different religious (or non-religious) backgrounds, from different socioeconomic backgrounds, or so forth. Intersectionality can affect many aspects of an LGBT+ person's life.

Writing Characters of Different Sexualities

-

1Understand sexuality. Before writing a character who has a different sexual orientation than you do, make sure you have an understanding of sexual orientation and how one sexuality is differentiated by another sexuality. For example, asexuality isn't celibacy—it's lack of sexual attraction, and asexual people can still be in romantic relationships.[4] Do research on the sexuality that you want your character to be.

- Sexuality is a spectrum, and isn't black-and-white or 50/50. For instance, an otherwise-gay man can have a celebrity crush on a woman, a bisexual or pansexual person can have a gender preference,[5] and an asexual person can be gray-asexual and occasionally feel sexual attraction.

-

2Decide on your character's sexuality. Lots of people aren't just "gay" or "straight"—there are many gray areas. Decide on your character's sexual orientation, and if you wish, their romantic orientation—which is who they're romantically attracted to.

- Straight or heterosexual characters are not LGBT+, as they are exclusively attracted to the opposite gender.[6] For example, a woman who dates cisgender and transgender men would be straight.

- Gay or lesbian characters are attracted to only people of their gender identity. Gay men would be attracted to men, and lesbian women would be attracted to women. (The word "gay" can be used to describe a girl, but the term "lesbian" can't be used for a boy.)[7]

- Bisexual or pansexual characters are attracted to two or more genders. The difference between bisexual people and pansexual people depends on the individual's definition of their sexuality. Some people identify as both "bisexual" and "pansexual", though others identify with one term over the other.[8]

- Asexual characters lack sexual attraction.[9] Some asexual people may simply not see people as "sexy" and be ambivalent towards sex, whereas others might be grossed out or repulsed by sex. (There's also gray-asexual, meaning they occasionally experience sexual attraction, and demisexual, where they can only feel sexual attraction to people they have a strong bond with.)

- Aromantic characters lack romantic attraction.[10] These characters may find other characters sexually attractive, but they do not desire a romantic relationship.

Sexual or Romantic Orientation: What's the Difference? Sexual orientation is based on what gender(s) someone finds sexually appealing (i.e., who they find sexy). Romantic orientation is based on who they gain romantic feelings for, such as crushes or people they want to date or marry. It's possible to have different sexual and romantic orientations, or to experience one type of attraction and not the other.

-

3Consider their history. Have they come out, and if so, to who? Have they faced any bigotry? How have people reacted to them? What is their attitude towards their sexuality? Figuring out what they have faced and how they have adapted is important to understanding who they are today.

-

4Decide how open they are about their sexuality. People come out throughout their whole lives, not just a few times.[11] That being said, some people prefer to share their sexuality more than others. Does your character prefer to be open about their sexuality, keep it relatively hidden, or somewhere in between?

- Your character's history will play a role in how open they are. For instance, someone who was a victim of bullying or abuse or who grew up in a homophobic environment may be more private about their sexuality than a character who grew up in a supportive area and wasn't bullied.

-

5Learn about misconceptions about sexuality. Some myths about sexuality can badly influence a character if you aren't aware of them. Things to look out for include:[12] [13]

- It's not always obvious. Being flamboyant or having certain traits doesn't mean someone's gay (or any other orientation), and lacking these traits doesn't mean they aren't.

- People don't "turn" a sexuality. Someone doesn't "go gay" because of a bad straight relationship or traumatic experience, and it's not possible to make someone straight. (And while some abuse victims may avoid relationships or become sex-averse due to trauma, this is different from being aromantic or asexual.)

- There's no "man" and "woman" in same-gender relationships. In healthy relationships, partners view each other as equals and responsibilities are typically based on what either person is good at and/or enjoys.

- Bisexual and pansexual people aren't into everyone they meet. Nor are they more willing to be polyamorous or cheat.

- Asexuality and aromanticism are real. While some people are late bloomers, it's entirely possible for someone to go through their whole life without experiencing romantic or sexual attraction.

- Not all asexual people are repulsed by sex. Some people are indifferent to it, prefer to deal with their needs on their own, or will have sex with a partner. It depends on the person.

-

6Consider conflicts they might have faced. Characters with different sexualities may encounter conflict related to their orientation, which can affect how they feel about themselves. How do they deal with hostility? How have past interactions affected them? Has it affected their relationships with others, or their ability to trust people? Things they may encounter or have experienced include:

- Confusion about why they're attracted or not attracted to someone

- Not understanding why relationships don't feel right

- Feeling pressured to act straight or interested in sex

- Lack of resources on healthy relationships and safe sex

- Harassment or fetishization

- Homophobia, biphobia, panphobia, or aphobia

- Discrimination

- Heteronormativity (i.e., people assuming they're straight)

Writing Characters of Different Gender Identity

-

1Understand gender identity. Gender identity is often confused with assigned sex, but they're different things. Assigned sex (sometimes incorrectly referred to as biological sex) is what sex organs a person was born with, while gender identity is the gender that a person identifies as and wishes to be addressed by.[14]

- Gender identity and sexuality are different things, and don't correspond. Trans people can be straight, gay, bisexual, pansexual, asexual, or any other sexual orientation. They're not straight or gay by default.[15]

- Gender expression (e.g., clothing, hairstyles, or makeup) doesn't necessarily indicate your character's gender identity. A boy can wear a skirt or have long hair and still identify as a boy, and a girl can bind her chest and wear "boy's" clothes while still identifying as a girl.[16] While gender expression often a huge part of a trans or nonbinary person's self-expression, someone's gender is defined by their identity, not by their gender expression.

-

2Decide on your character's gender identity. Your character's gender identity may or may not be important to the story. Regardless, if you're writing a character with a different gender identity, you'll need to choose their gender identity.

- Cisgender (sometimes abbreviated to cis) is not an LGBT+ identity; it means that a character identifies with the gender that corresponds with their assigned sex. For example, someone who's assigned male identifying as a boy would be cisgender.[17]

- Transgender (sometimes abbreviated to trans) means that a character identifies with a gender that does not correspond with their assigned sex. For example, a person who was assigned male and identifies as female would be a transgender girl and would be referred to as a girl.[18]

- Nonbinary (sometimes spelled "non-binary") is an umbrella term that refers to anyone whose gender identity falls outside of exclusively male or female.[19] The umbrella term transgender encompasses nonbinary people, but not all nonbinary people personally identify as transgender.[20]

- Agender characters have no gender or have a gender-neutral gender identity.[21] They may choose to use non-gendered pronouns, such as they/them or xie/xir, and/or gendered pronouns (such as she/her or he/him).[22]

- Bigender isn't limited to just male and female. A character can feel both like a boy and like no gender at the same time, for example.[23] They may choose to use different pronouns, including gendered ones (like he/him or she/her) and/or non-gendered ones (like they/them).

- Someone who is genderfluid can alter between various genders anywhere on the gender spectrum.[24] They may choose to use different pronouns, including gendered ones (e.g. he/him or she/her) and/or non-gendered ones (e.g. they/them).

- Demiboys and demigirls only partially identify as boys or girls.[25]

- There are also more uncommon identities which you can research.

-

3Design your character. Unlike sexuality, sex and gender tends to play more of a role in life from early on. A trans character may have difficulty with having been socialized in gendered ways or growing up as the wrong gender, and if they've gone through puberty, they may have some features that don't match societal beauty standards or that they're self-conscious about.

- Think about how they choose to present their gender. Do they want to appear more masculine, more feminine, androgynous, or deliberately ambiguous? How do they go about doing that - does it affect their style or behavior?

- Is "passing" important to them? Some trans people don't want other people to know they're trans unless necessary, whereas others are fairly open about it. This can also be an issue for nonbinary people whose gender expression leans more masculine or feminine.

- Consider if and when they were able to have access to hormones and other treatments. A twenty-year-old who started estrogen two months ago will look different from a twenty-year-old who transitioned at age five and had puberty blockers.

- Without puberty blockers, puberty can be quite traumatic for trans people. Even if they have since gotten hormones and look great, they will probably have many bad memories.

-

4Consider whether your character experiences dysphoria, and to what extent. Gender dysphoria is when someone experiences a mismatch between their true gender and their expected gender or behavior. Dysphoria is different for every person, whether it comes to severity or what it affects. Does your character experience dysphoria, and if so, what triggers it?

- Some transgender people experience moderate to severe dysphoria and struggle if they don't have coping mechanisms. Other people experience minimal dysphoria, or don't experience it at all. The majority of trans people also experience gender euphoria, or a positive feeling when their true gender is validated.[26]

- Nonbinary people can also experience gender dysphoria and euphoria.

- Dysphoria can affect different parts of the body and aspects of life. For instance, a trans man might feel dysphoria about how he's perceived socially and about his height and voice, but not his breasts or genitals.

Tip: Dysphoria is not always extremely distressing, and it may not even be particularly obvious. While some trans people do experience extreme distress if they see their genitals, others might just feel discomfort or unsettled if they're misgendered or presenting as the wrong gender. There's a lot of nuance.

-

5Understand common misconceptions. There are many misconceptions about transgender people that cisgender people come up with. Common ones to be ruled out are:

- It's not a phase. It's very uncommon for people to detransition or grow out of it.

- Not everyone knows right away. Some people know their gender from an early age, but many don't realize it until they reach puberty or adulthood. It's also possible to know earlier on, but not come out due to a lack of knowledge on the subject, internalized transphobia, or living in an unaccepting environment.

- Trans people aren't "just gay." They can be gay, but gender identity and sexual orientation don't correlate.

- Nonbinary identities are real. Genders such as nonbinary, bigender, agender, genderfluid, and more are legitimate. Gender identity is a spectrum, not a binary.

- Not everyone takes hormones or has surgery. Many transgender people are not comfortable with having surgery or taking hormones. Even if they are comfortable with it, other factors can make it impossible to have hormones/surgery, such as health problems, financial issues, or unsupportive/unsafe environment.[27]

-

6Consider how they have adapted. Living in a cis-centric world is difficult for a trans person, especially depending on how accepting the environment is. What tricks have they developed to stay safe? How do they cope? What have they faced in the past, and has it impacted their ability to trust others or feel safe? Common issues faced include:

- Public restroom safety

- Picking "male" or "female" on documents

- Street harassment

- Trying to look "presentable enough" to avoid discrimination (When? How much? Are they a bad person for doing this?)

- Cruel family members

- Mental health issues, suicidal thoughts

- Discrimination

Avoiding Stale Writing

LGBT+ representation in fiction too often falls into the same trite plotlines and stereotypes. Here is how to avoid these and write something more interesting and creative.

-

1Recognize the stereotypes that exist. The LGBT+ community is very diverse, and people who share a sexuality or gender identity could be very different from each other. Watch out for stereotypes, because these can undermine your ability to write a three-dimensional character. Here are some common tropes:[28] [29] [30]

- Feminine gay man, gay man who only serves to be a girl's sidekick

- Masculine lesbian

- Gay couple whose only desire is to have children

- Promiscuous, sly bisexual/confused bisexual

- Frigid or evil asexual

- Transgender person who is deceptive or a freak

- Flamboyant or "camp" LGBT+ characters

-

2Remember the difference between sexuality and gender expression. Liking men does not make one feminine, and liking women does not make one masculine. Fiction is filled with gay men who love shopping and detest football, and tough lesbians who play rough sports. Recognize the stereotypes and work on making your character original.

- Of course, there are some feminine gay men and some masculine lesbians. If you are writing one of these characters, make sure that you are giving them plenty of unique and multilayered traits too, so that they are more than a caricature.

-

3Choose your words with care. Some terms have been used in degrading and dehumanizing ways, and can be very hurtful and alienating to LGBT+ readers. It can also suggest to readers who aren't in the know that it is okay to use these words to describe someone else. Use compassion when selecting words, and be aware of how this affects the message you send to your readers.

- Always have the narrative refer to a transgender person as their correct gender (the gender that they want to be referred to as), even if others are misgendering the character.

- If you have a character who uses these words, make it clear in the narrative that this character is being hurtful. For example, if somebody calls Laquisha a "d*ke," show how this upsets her, and/or have someone stand up for her.

Warning: Be careful with the word "queer." Some LGBT+ people have reclaimed it and may self-identify as it, but others view it as a slur. If you do have a character self-identify with the term, use it as an adjective rather than a noun, don't have non-LGBT+ characters casually use the term, and don't use "queer" as a synonym for "LGBT+" or a specified identity.[31] [32]

-

4Make your LGBT+ character a character in their own right. Some writers use LGBT+ characters as one-dimensional plot devices, used to further the development of straight and cis characters, or to serve as sidekicks to them. However, this is disappointing to LGBT+ readers that want to see LGBT+ characters pushing the plot forward themselves.

- This doesn't mean your LGBT+ characters shouldn't teach other characters anything, simply that there should be more to them than only this.

-

5Avoid queerbaiting. Queerbaiting is when characters are heavily implied to be LGBT+, sometimes to the point of romantic or sexual activity together, only to not be given LGBT+ identities and never get together (and sometimes be pushed into straight relationships or reveal it was "just a phase"). This is disappointing to many LGBT+ readers, who want to see characters with canon LGBT+ identities and relationships.[33] [34] Instead, give the characters clear LGBT+ identities and relationships.

- Spell out the characters' desires and identities. Does the main character want to kiss the boy in his class because he's curious about what it's like, and later realizes he's gay or bi? Does a "boy" desperately try to grow their hair out to a more ambiguous length and admire the designs of girls' clothing, and admit to their friends that they think they're bigender? Does a girl tell her female best friend that she'd marry her if no guy will - and secretly mean it?

- Try to avoid characters who "don't like labels." It can seem like you don't want to admit your character is LGBT+. Give them an identity, even if it's just "I'm not straight/cis, but I don't know what I am."

Warning: Some behaviors and stereotypes are based in queerbaiting, like two girls kissing to seem sexy or get a guy's attention. Leave this kind of content out of your story, or have other characters call them out on it.

-

6Recognize that same-gender couples are, on average, just as sexual as mixed-gender couples are. There is no need to fixate on sex (unless you are writing erotica), nor do you need to avoid showing the characters doing anything more than holding hands.[35]

- If all the mixed-gender couples are kissing when the bell tolls for New Year's, let the same-gender couple kiss too. They can have the same romantic opportunities.

-

7Be cautious with killing off LGBT+ characters. It's not inherently harmful to kill off an LGBT+ character, particularly if you have multiple LGBT+ characters in a story where any character could die. However, if only the LGBT+ characters die or only cis- and straight-passing characters are alive at the end of the story, this can send a very unfortunate message to LGBT+ readers: that they're not as worthy or important as non-LGBT+ people, and/or that suicide is the most common and sensible option.[36]

- Ask yourself why you want to kill off this specific character. Is it to move the story forward in some way, or is it simply to raise the death count, shock, or send a message (like to show that others should have treated the character better)? If it's the latter, reconsider killing the character.

- Consider the manner of death, too: if the character dies by suicide or murder, that will be received differently than if they were to die in an accident or from natural causes (like illness or old age).

- If your story absolutely requires killing an LGBT+ character, make sure that there are other LGBT+ characters who survive and have bright futures ahead of them.

-

8Name the sexuality or gender identity. Tell readers that Lana is bisexual, not just confused, and Richard is asexual, not broken. Labeling their identity can help readers who share the identity feel validated, and help readers who don't have that identity learn and empathize more. You may even have a reader or two who realizes they have that identity thanks to your story.

Community Q&A

-

QuestionI'm creating a web comic where the characters are all demons. Some of them are a part of the LGBTQ+ community. Would that be too offensive and rude? I don't want to be disrespectful.

Community AnswerAs long as their being LGBTQ+ isn't portrayed as something that makes them demonic or adds to their evil, it won't be offensive or rude.

Community AnswerAs long as their being LGBTQ+ isn't portrayed as something that makes them demonic or adds to their evil, it won't be offensive or rude. -

QuestionI support LGBT people, but it's really weird for me writing transgender characters. Does this make me a bad person?

Community AnswerNot at all! Even if you're accepting of transgender people, it can still be difficult to immerse yourself in the culture, language, pronouns, etc. when it's so different from what you've known your whole life. However, don't be afraid to try! There's always a need for more LGBTQ+ characters, and this gives you an opportunity to really learn about what it means to be transgender and how it influences someone's thoughts and personality.

Community AnswerNot at all! Even if you're accepting of transgender people, it can still be difficult to immerse yourself in the culture, language, pronouns, etc. when it's so different from what you've known your whole life. However, don't be afraid to try! There's always a need for more LGBTQ+ characters, and this gives you an opportunity to really learn about what it means to be transgender and how it influences someone's thoughts and personality. -

QuestionWould be a bad idea to make the villain LGBT (pansexual, to be exact), even if there are other characters, good guys, who are also LGBT? There are other pan characters (who aren't horrible), but it's a nagging concern.

Luna RoseTop AnswererThat's fine. It helps if you avoid hypersexualizing or negatively stereotyping the villain, such as making them obviously queer while the others could pass for straight. Showing good pan characters will make it clear that you don't believe pansexuality is evil, especially if you are showing pan characters in healthy relationships. This is a tricky one, and it may be helpful to talk a bit with some LGBT+ friends (online or in-person) and hear their advice.

Luna RoseTop AnswererThat's fine. It helps if you avoid hypersexualizing or negatively stereotyping the villain, such as making them obviously queer while the others could pass for straight. Showing good pan characters will make it clear that you don't believe pansexuality is evil, especially if you are showing pan characters in healthy relationships. This is a tricky one, and it may be helpful to talk a bit with some LGBT+ friends (online or in-person) and hear their advice.

References

- ↑ https://refiction.com/articles/lgbt-characters

- ↑ https://www.writersdigest.com/publishing-insights/6-pitfalls-writing-lgbtqi-characters-teen-fiction

- ↑ http://bang2write.com/2017/05/how-to-write-better-lgbt-characters.html

- ↑ https://www.healthline.com/health/what-is-asexual

- ↑ https://www.healthline.com/health/bisexual-vs-pansexual#learn-more

- ↑ https://www.glaad.org/reference/lgbtq

- ↑ https://www.verywellmind.com/what-does-lgbtq-mean-5069804

- ↑ https://www.healthline.com/health/bisexual-vs-pansexual#learn-more

- ↑ https://www.glaad.org/reference/lgbtq

- ↑ https://www.glaad.org/reference/lgbtq

- ↑ https://www.stonewall.org.uk/node/55084

- ↑ https://www.stonewall.org.uk/node/55084

- ↑ https://adm.viu.ca/positive-space/lgtb-myths-facts

- ↑ http://www.springhole.net/writing/about-sexuality-and-gender-expression.htm

- ↑ https://www.stonewall.org.uk/node/55084

- ↑ https://www.verywellhealth.com/gender-expression-5083957

- ↑ https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-does-it-mean-to-be-cisgender-3132607

- ↑ https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-is-transgender-5074206

- ↑ https://www.glaad.org/reference/transgender

- ↑ https://www.verywellmind.com/what-does-it-mean-to-be-non-binary-or-have-non-binary-gender-4172702

- ↑ https://www.healthline.com/health/agender#definition

- ↑ https://www.healthline.com/health/agender#pronouns

- ↑ https://www.verywellmind.com/what-does-it-mean-to-be-non-binary-or-have-non-binary-gender-4172702

- ↑ https://www.verywellmind.com/what-does-it-mean-to-be-non-binary-or-have-non-binary-gender-4172702

- ↑ https://www.healthline.com/health/different-genders#a-d

- ↑ https://everydayfeminism.com/2015/06/these-5-myths-about-body-dysphoria-in-trans-folks-are-super-common-but-also-super-wrong/

- ↑ https://www.stonewall.org.uk/node/55084

- ↑ http://www.queerty.com/the-over-used-stereotypical-characters-that-most-gay-books-include-20100104

- ↑ https://refiction.com/articles/lgbt-characters

- ↑ https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/CampGay

- ↑ https://thesafezoneproject.com/faq/isnt-queer-a-bad-word/

- ↑ https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/is-queer-ok-to-say-heres-why-we-use-it

- ↑ https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2018/02/26/what-is-queerbaiting-everything-you-need-to-know/

- ↑ https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/queerbaiting-lgbtq-ariana-grande-celebrities-james-franco-jk-rowling-a8862351.html

- ↑ https://deaddarlings.com/closet-writing-gay-characters/

- ↑ https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/BuryYourGays