This article was co-authored by Bryan Sullivan. Bryan Sullivan is a Bartender and the Owner of Bryan Sullivan Bartending in Seattle, Washington. With over 10 years of experience, he specializes in craft cocktails and has a thorough knowledge of beer, wine, and champagne. He currently holds a MAST Class 12 Mixologist Permit and has provided bar service for 100s of events. Additionally, his business has a 5-star rating and is a listed vendor on The Knot.

This article has been viewed 211,823 times.

Lambic beer is a unique, archaic form of beer that is quite different than modern, commonplace ales and lagers. Authentic lambics are only produced in the Senne River Valley region of Belgium near Brussels. They are unusual because, like beers brewed in ancient times, they are spontaneously fermented with wild, naturally occurring yeast and bacteria. The yeast and bacteria reside in the air as well as in brewery equipment and entire brewery structures such as decrepit roofs. The specific, ideal microbial profile that exist in the Senne Valley enables the creation of true lambic beer that cannot be reproduced elsewhere. The brewery equipment that harbors and nurtures various kinds of yeast and bacteria is never fully cleaned and sanitized. The decaying, seasoned structures of breweries are maintained as such so that important microbial flora are not lost. This is in sharp contrast to modern ale and lager breweries that use pure, laboratory-raised strains of brewing yeast and constantly work to ensure that the beer is not contaminated with microbes other than their pure strain of brewing yeast. Brown, oxidized hops that have been aged for three or more years are also used to make lambics. Unlike the green, unoxidized hops that are used to make conventional beer, the oxidized hops do not contribute much or any bitterness or hop character. They are used primarily for their natural preservative properties. The wild, unconventional nature of lambic beer makes for a complex beverage that is best experienced when served at the appropriate temperature and in suitable glassware.

Steps

-

1Find an authentic lambic beer. Authentic lambic beer must be from Belgium, and the label of true lambic beer should display the word “lambic” (or "lambiek"). Beer that is spontaneously fermented but is not from Belgium cannot be true lambic beer. Lambics are typically aged for six months to three years, and young and old lambics are traditionally blended. Lambics should be made from natural ingredients and not artificially flavored or colored. Lambics by Lindeman's, for example, are usually artificially sweetened. If the ingredients are listed on the bottle, look for malted barley, unmalted wheat, and hops. Fresh, whole fruit is also frequently an ingredient, and is added to the base lambic beer. The fruit is then fermented in the beer, as it is rich in fermentable sugars. Pits and other unfermentable material are removed before bottling. Look for beer that is packaged in 375 mL and 750 mL champagne bottles. Bottles of lambic are corked like wine and champagne, but some will have bottle caps that have been capped over corks. The cork will not be visible until the cap is removed from the bottle.[1]

- Fruit lambics are commonly labeled as kriek, pecheresse or peche, framboise, and cassis. These lambics are named according to the type of fruit that they have been made with, and will typically show pictures of the fruit that they are made with on their labels.

- Gueuze (also spelled geuze) and faro are traditional styles of lambic beer that are not made with fruit. It is customary for gueuze to be a blend of one year old, two year old, and three year old lambics. Gueuze can be quite sour or tart, while faro is sweeter, as it is traditionally made with added sugar. The sour and tart qualities are primarily a result of certain bacteria, such as acetic acid and lactic acid producing bacteria, that act upon the fermenting beer.

- Unblended or straight lambic can be young six month old lambic or considerably older, and traditionally contains very little carbonation. Faro is traditionally unblended. Other types of lambic tend to be highly carbonated.

-

2Chill the lambic to serving temperature. Chill in the range of about 4C to 12C (40F to 55F). Use cooler temperatures for fruit lambics and warmer temperatures for gueuze and unblended straight lambics. Warmer temperatures will bring out the complicated aromas and overall flavors that are produced by the many different microorganisms that ferment the beer. Oak fermentation vessels, long aging periods, the ingredients used, and other factors also influence the aroma and overall flavor. As refrigerators tend to be colder than the optimal serving temperatures, set a chilled lambic out on the counter for a little while so that it can warm up slightly before it is opened and poured.

- The general rule is that you should serve the darker and stronger beers warm.

Advertisement -

3Set out the correct glassware. Use tulip, snifter, and stange (slender cylinder) glasses for gueuze and fruit lambic. Use flute glasses for gueuze, fruit lambic, and faro. Most unblended lambics can be served in flute and strange glasses. Use personal preference when choosing among types of glasses. Different glasses will modulate aromas and flavors in certain ways, and specific lambics may be more enjoyable when drunk from a certain type of glass. Wine glasses complement lambics well, but short stems are generally desired. Also, collins glasses can be substituted for stange glasses. Specific lambics may be paired with proprietary glassware that is provided by the brewery. Consider how much capacity certain glasses have, and be sure that you can fill them appropriately. Also take into account that most lambics are highly carbonated and will foam a lot, and that it is usually desirable to serve such lambics with a good amount of foam.

- Different beer glasses affect how you experience that beer. It can change head retention, the amount and speed at which you drink, and how the beer aromas travel to your nose.

- If you love a stout, invest in a stout glass.

-

4Remove the foil if desired. Cut or tear off the foil that may be wrapped around the cap and bottle neck. Cut it neatly around the cap with a wine foil cutter or just tear it off like a brute. Alternatively, just pop off the cap without removing the foil, as the foil should not hinder the action of the bottle opener or hold down the cap. However, the bottle opener may slip somewhat if the foil is not removed initially.

-

5Pop off the cap. If a cap exists, pop it off with a bottle opener. The cap may be larger than standard beer bottle caps, so some standard bottle openers may not work well.

- Try using large openers that are typically used by bartenders.

-

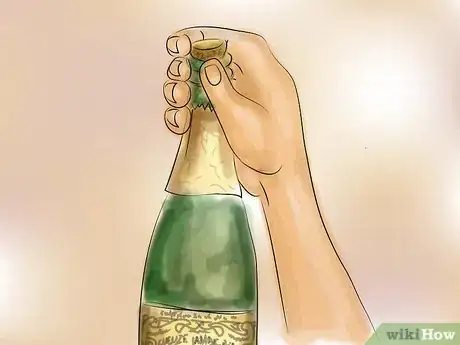

6Uncork the bottle. The bottle may be corked with a cork is that is underneath the cap, or with a large bulbous champagne cork. If the cork is under the cap, use a corkscrew wine opener to remove the cork.

- Bulbous champagne corks should be kept in place by a wire cap until the bottle is ready to be opened, as the cork can shoot out explosively if not kept in place.

- To uncork a bulbous cork, begin by removing the wire retainer.

- Then, if desired, use your thumb or fingers to loosen the cork. It will most likely pop out with a good deal of force and fly across the room or up into the sky. The cork should pop out after the cork has been only slightly moved out of the bottle. To prevent the cork from popping out of the bottle and to prevent excessive foaming, hold your hand firmly over the cork while working it free of the bottle, or even hold a cloth napkin or towel over the cork while pushing it out. The napkin or towel should hold the cork within it.

- Allow for foam to be released from the bottle as it is opened, especially of the cork was allowed to pop out freely. Don't further agitate the lambic by moving your arm or jumping around, because then it will just foam more and much of the lambic will end up on the ground or on your clothes.

-

7Pour the lambic. Most available lambics such as gueuze and fruits lambics are highly carbonated, and will foam very easily. Try to get a good amount of foam when pouring, but not so much that there is not enough liquid beer. The exact amount of foam that is desirable for specific lambic beers can certainly vary, and there may be no perfect amount of foam for any lambic. Keep in mind that lambics are all quite different, and are the result of spontaneous, natural conditions.[2]

- Begin by pouring somewhat slowly down the side of the glass while holding the glass at an angle in your hand. This will minimize excessive foaming.

- When the glass is about one quarter to half full, gradually move the glass upright. This will cause a decent, desired amount of thick, dense or rocky foam to form as the pour is completed. Increase the speed by which the glass is tilted upwards and the height from which the beer is poured to increase foam formation. Alternatively, pour at a lower height and pour for a longer period of time down the side of the glass to minimize foam formation. A fair amount of the glass should usually be occupied by foam, as the foam has a wonderful appearance and is often an important part of lambic beer.

- The poured lambic may appear quite hazy, as it is traditional for lambics to be unfiltered. Such unfiltered lambics will also have a sediment on the bottom of the bottle that can produce cloudiness. To avoid a cloudy appearance, do not agitate the bottle before pouring, pour gradually without tilting the bottle much, and do not pour out the very last amount of beer. The bacteria present during fermentation can also be responsible for making lambics hazy. These bacteria can produce a slime that is subsequently broken down over time, and the remnants of the slime result in a haze. This type of haze is perfectly acceptable. Filtered lambics are not unusual, so don't be surprised if one lambic is hazy and another is not. Also, unfiltered lambics may appear quite clear if the lambic was not agitated and provided with enough time to allow the particles in the lambic to settle out naturally. In this instance, the lambic may pour clear initially, then become cloudy as the dregs of the bottle are poured into the glass. Fruit lambics may be quite dark, depending on the kind of fruit that was used.

-

8Smell and taste the lambic. Expected aromas are typically described as fruity, citric, horsey, barnyard, goaty, sweaty, hay, horse blanket, earthy, and acidic. Lambics can taste quite sour and tart, and can be reminiscent of sherry or cider. Tannic astringency can also be present, and the oak that the lambic may have been aged in can be detectable. Hop bitterness should be low or absent. Undesirable aromas and overall flavors may be described as cigar-like, smoky, enteric, and cheesy. Very sweet fruit lambics may have added sugar primarily for the American market, but authentic, artisanal fruit lambics such as those brewed by Cantillon or Hanssens should only impart sweetness that is from fresh fruit and fruit juice. The flavor and color of the type of fruit that was used to make a fruit lambic should be apparent.

Warnings

- When uncorking a champagne-style cork, don’t let it collide with something that is alive or delicate.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Don't drink and drive⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Don't drink this to excess. It is to be enjoyed.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/03/dining/03beer.html

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0tKgSGNGoE0

- http://www.ratebeer.com/Beer-News/Article-504.htm

- https://www.lambic.info/Serving_Lambic

- https://www.thekitchn.com/beer-guide-what-is-lambic-beer-78258

- https://www.splendidtable.org/story/lambic-beer-your-comprehensive-guide