This article was co-authored by Laura Marusinec, MD. Dr. Marusinec is a board certified Pediatrician at the Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, where she is on the Clinical Practice Council. She received her M.D. from the Medical College of Wisconsin School of Medicine in 1995 and completed her residency at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Pediatrics in 1998. She is a member of the American Medical Writers Association and the Society for Pediatric Urgent Care.

There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 31,037 times.

Reye's (or Reye) syndrome is a fairly rare but serious medical condition that leads to swelling in the liver and brain, confusion, seizures and eventually loss of consciousness. The condition most often affects kids who are recovering from viral infections — typically the flu or chickenpox.[1] Reye's syndrome can become life threatening fairly quickly, so early detection and treatment is important. Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid or ASA) is associated with Reye's syndrome in children, so caution must be taken giving any to them. Never give your children aspirin if they have chickenpox or flu-like symptoms or are recovering from these infections.

Steps

Being on Alert for Reye's Syndrome

-

1Recognize the initial signs. People with Reye's syndrome tend to become ill very suddenly. Signs typically appear about three to five days after the onset of viral infections such as influenza, chickenpox or the common cold, but, the signs may occur as late as three weeks after a viral infection.[2] The symptoms are quite different from the flu or common cold, which are upper respiratory infections — the initial signs of Reye's syndrome can mimic food poisoning and the stomach flu. The initial signs of Reye's syndrome include:

- Continuous vomiting (lasting for many hours)

- Irritable behavior

- Unusual sleepiness or lethargy

- Moderate-to-severe diarrhea and rapid breathing (for little kids, or those younger than two years old)[3]

- Dropping blood sugar levels with higher levels of blood acidity.

- Swelling of the liver and brain

-

2Watch for additional symptoms. After the initial onset of signs, it usually takes a day or two for the more serious symptoms to develop and noticeable changes in mental status to occur. As Reye's syndrome progresses and gets more serious, additional symptoms often include:

- Tiredness

- Aggressive/irrational behavior

- Confusion/disorientation

- Weakness or paralysis in the limbs

- Seizures, loss of consciousness and coma[4]

- If you see this pattern of signs or symptoms in your child or yourself, you need to get to a hospital or clinic for emergency treatment quickly.

- Changes in mental status can include aggressiveness, agitation, amnesia, hallucinations (seeing and hearing things) and progressively reduced consciousness until the person lapses into a coma.

Advertisement -

3Understand the risk factors. The cause of Reye's syndrome is unknown, but it occurs almost exclusively in children younger than 18 years (particularly between four to 12 years) and is most common in the late fall and winter months.[5] Most children diagnosed with the syndrome have a history of recent viral infection (influenza, chickenpox, common cold, rotavirus), which they are either still dealing with or just getting over. In addition to the association with certain viral infections, many affected children have a history of being given aspirin to control their fevers.

- Since parents have been educated about the potential dangers of aspirin use for children, the incidence of Reye's syndrome has dropped off significantly. More specifically, there are only a few documented cases of Reye's syndrome in the United States per year now, although back in 1980, there were about 500 cases.[6]

- People with fatty acid oxidation disorders (unable to break down fats because an enzyme is missing or malfunctioning) and other metabolic disorders appear to be at higher risk for Reye's syndrome.[7]

- Exposure to insecticides, herbicides and paint thinners may also increase the risk of developing Reye's syndrome.

-

4Avoid serious consequences and complications. Although most people (primarily children and teenagers) who develop Reye's syndrome survive, varying degrees of permanent brain damage are relatively common in survivors.[8] The brain inflammation associated with Reye's is what causes the seizures, loss of consciousness (coma) and eventual permanent brain damage. The key to avoiding serious consequences and complications is getting the correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment quickly — within a few days of the onset of any symptoms. Left untreated, Reye's syndrome is sometimes fatal, but almost always destructive to the brain.

- Brain damage can cause intellectual/developmental disability, behavioral problems, deafness, arm / leg paralysis and/or a long-term coma.

- Since the 1980s, the risk of death from Reye's syndrome has decreased from 50% to less than 20% as a result of early diagnosis and aggressive therapy.[9]

Confirming and Treating Reye's Syndrome

-

1See a doctor immediately. If you've recognized some signs and symptoms of Reye's syndrome, contact your doctor immediately to be seen or go directly to the emergency room. Quick action is crucial, as fatality rates are less than 2% among patients in the early stages of Reye's, but greater than 80% among patients in the late stages.[10] A pediatrician or neurologist (brain specialist) might be more experienced recognizing and treating Reye's. There's no specific test for Reye's syndrome, although blood and urine tests can determine high risks for it (metabolic disorder, low blood glucose, high liver enzymes, fighting an infection).[11] Sometimes more-invasive diagnostic tests are needed to see if the brain and/or liver are inflamed:

- A spinal tap (lumbar puncture) can help diagnose inflammation in the brain and rule out other causes, such as meningitis or encephalitis. During a spinal tap, a little bit of cerebrospinal fluid is removed and analyzed.

- A liver biopsy involves inserting a long needle into the liver and taking a small tissue sample to see if there is inflammation and/or fat accumulation — common with Reye's syndrome.

- A computerized tomography (CT) scan or MRI can also identify abnormal changes in the brain and liver.

-

2Control the brain swelling. There is no cure or specific treatment for Reye's syndrome, but management of it centers around protecting the brain from irreversible damage by reducing swelling within the head.[12] Medications called osmotic diuretics are usually given to people with Reye's, which decrease the pressure within the head and increase overall fluid loss through stimulating urination.[13] Medications that lower ammonia levels are also used because it's known to increase brain swelling. In extreme cases, the pressure within the head has to be relieved by a decompressive craniectomy, which is an operation that involves cutting into the skull and draining the excess fluid.

- Patients with Reye's syndrome are usually admitted to an intensive-care unit (ICU) within a hospital and monitored for escalating neurological and metabolic problems.

- Once in the hospital, it's difficult to predict which patients get entirely better and which suffer brain damage. However, those patients who develop seizures due to brain swelling have the highest risk of brain damage (about a 30% chance).[14]

-

3Maintain electrolytes and prevent internal bleeding. Once the brain swelling is under control, doctors must also make sure that electrolytes (electrically charged minerals) in the blood are maintained because reducing fluid in the body with diuretics can deplete electrolytes.[15] Electrolytes are needed to control the movement of fluid between cells and allow for electrical signals to travel within nerves. Intravenous fluids consisting of glucose (for energy) and an electrolyte solution are usually given through an intravenous (IV) line while in the hospital.

- Medications are also needed to prevent internal bleeding due to liver dysfunction and abnormalities. As such, vitamin K and extra plasma and platelets are usually given to patients with advanced Reye's syndrome.[16] Medications may also used to prevent or treat seizures.

- Other concerns for people with Reye's include reversing any metabolic issues, preventing lung, kidney, or gastrointestinal complications and anticipating and preventing cardiac arrest (heart stoppage).

Warnings

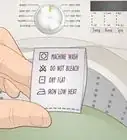

- Be aware that some over-the-counter medications (such as Pepto-Bismol and Alka-Seltzer for upset stomachs) contain salicylate compounds similar to aspirin — do not give these to children with colds or flus.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Although aspirin is approved for use in kids older than 2 years, it should never be given to children or teenagers who are recovering from chickenpox or flu-like symptoms.[18]⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reyes-syndrome/basics/definition/con-20020083

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001565.htm

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reyes-syndrome/basics/symptoms/con-20020083

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reyes-syndrome/basics/symptoms/con-20020083

- ↑ http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/miscellaneous-disorders-in-infants-and-children/reye-syndrome

- ↑ http://www.medicinenet.com/reye_syndrome/page4.htm

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reyes-syndrome/basics/causes/con-20020083

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reyes-syndrome/basics/complications/con-20020083

- ↑ http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/803683-overview#a7

- ↑ http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/miscellaneous-disorders-in-infants-and-children/reye-syndrome

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reyes-syndrome/basics/tests-diagnosis/con-20020083

- ↑ https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases_conditions/hic_Reyes_Syndrome

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reyes-syndrome/basics/treatment/con-20020083

- ↑ http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/miscellaneous-disorders-in-infants-and-children/reye-syndrome

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reyes-syndrome/basics/treatment/con-20020083

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reyes-syndrome/basics/treatment/con-20020083

- ↑ https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases_conditions/hic_Reyes_Syndrome

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reyes-syndrome/basics/definition/con-20020083

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...