This article was co-authored by Trudi Griffin, LPC, MS and by wikiHow staff writer, Christopher M. Osborne, PhD. Trudi Griffin is a Licensed Professional Counselor in Wisconsin specializing in Addictions and Mental Health. She provides therapy to people who struggle with addictions, mental health, and trauma in community health settings and private practice. She received her MS in Clinical Mental Health Counseling from Marquette University in 2011.

There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 16,565 times.

Awareness of hoarding as a phenomenon has grown due to cable TV shows and other media exposure, but it is still often misunderstood. Calling someone who has hoarding disorder “messy” or a “pack rat” minimizes the reality of this illness, which can have devastating impacts on social interaction, emotional health, financial stability, and physical safety. Hoarding disorder, like many other illnesses, can never really be “cured” — but it can be successfully treated with the right mix of treatment methods and an active support network.

Steps

Acknowledging the Problem

-

1Recognize hoarding as a defined illness. Hoarding used to be viewed as a personality quirk or as a subset of another mental health condition like obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). However, hoarding is now a specifically defined disorder in the DSM-5, the most recent edition of the essential manual for mental health professionals in the U.S. It is a legitimate illness that requires legitimate treatment.[1]

- According to the DSM-5, a person with hoarding disorder: A) has severe difficulty parting with possessions regardless of actual value; B) thinks saving items is necessary and feels distress at the thought of discarding them; C) accumulates possessions to the degree that they clutter living areas and limit functionality (such as by blocking the stove or filling the tub); D) has significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas; E) does not have a brain injury or other disease or disorder that better explains the behavior.

-

2Don’t confuse collecting with hoarding. What is the difference between a person with an enormous magazine collection and a person who has hoarding disorder who has a lot of similar materials? Why is one an eccentric or even annoying habit but “okay,” while the other is a mental illness? Sometimes the line is a fine one, but organization and intent usually distinguish them.[2]

- Collectors are almost always precise and particular about the organization, categorization, and display of their chosen items (like dolls or antique toasters). The items may fill or even clutter areas of the house, but don’t usually impede normal activities. People who have hoarding disorder may insist otherwise, but their accumulations of items are almost always disorganized and impediments to normal household functions.

- Collectors derive pleasure or joy from the items they accumulate and display. People who have hoarding disorder have an anxiety disorder that causes fear at the notion of discarding items.[3]

Advertisement -

3Identify negative impacts. Keeping a bunch of junk in the garage or spare bedroom does not necessarily mean that someone has a hoarding disorder. Hoarding disorder inevitably causes significant negative impacts for the sufferer and those closest to him or her.[4]

- People who have hoarding disorder, for instance, tend to rarely leave home, often out of embarrassment and/or fear that someone will come and take their possessions. They often therefore face difficulty finding and keeping jobs, and may face evictions or other legal action due to unsafe living conditions.

- People living with someone who has hoarding disorder may be affected by the accumulation of items throughout the house, but other family and friends are also negatively impacted. They often find opportunities for interaction with the person who has hoarding disorder significantly reduced, and may feel shame or embarrassment by association with the person who has hoarding disorder.

-

4Examine potential links with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Although they are now defined as distinct conditions, hoarding and OCD overlap in about twenty to forty percent of cases. There is obviously an element of obsession involved in hoarding, but it also presents in unique ways and requires distinctive treatments. This is one of many reasons why a professional diagnosis of hoarding disorder is so important as a first step toward treatment.[5]

- Individuals who have both OCD and hoarding disorder may need related yet separate treatment regimens to deal with each. Behavioral therapy and possibly medication will likely be involved, but there is no “one size fits all” treatment for these conditions, either individually or in tandem.[6]

Getting Professional Help

-

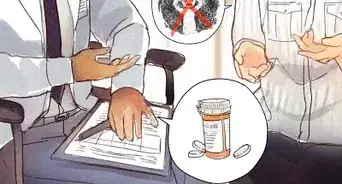

1Assemble an experienced healthcare team. An individual with a chronic physical illness like diabetes requires a coordinated team of medical professionals to successfully manage the condition. The same is true for the chronic illness known as hoarding disorder. Physicians, mental health professionals, and others with experience dealing with the condition need to work together in order to develop a well-rounded treatment regimen.[7]

- Hoarding disorder will typically be diagnosed by a psychiatrist or other mental health professional. He or she may utilize tools like the Hoarding Rating Scale or Hoarding Assessment Battery, both of which utilize observations and questions to help determine if the condition exists.[8]

- If and when hoarding disorder is diagnosed, the mental health professional, the patient’s primary care physician, and any specialists or other professionals involved will ideally work together to develop a coordinated treatment approach. Don’t be afraid to demand communication and coordination in care for yourself or a loved one with hoarding disorder.

-

2Address behaviors and perspectives with therapy. For most people with hoarding disorder, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a mental health professional is the front-line treatment option. CBT can often help people who have hoarding disorder and who are resistant to treatment or in denial accept that there is a problem, and then possibly develop solutions and coping mechanisms.[9] [10]

- CBT can help a person who has hoarding disorder identify the causes of his or her condition, which might include a traumatic childhood incident or a family history (diagnosed or not) of the illness. From there, the therapist and patient can work on developing organization and categorization skills, improving coping, decision-making, and relaxation skills, and slowly taking steps toward reducing the accumulation of items.

- CBT takes time to make progress in treating hoarding disorder, potentially months or even years. But, regardless of what TV shows on the subject may indicate, there is no lasting “quick fix” for hoarding.

-

3Supplement therapy with prescribed medications. Because hoarding disorder is still relatively new as a distinct condition, treatment plans may be somewhat less standardized. For instance, there is still disagreement regarding if and how to use medications to treat hoarding disorder. However, some people with the condition do seem to respond well to certain antidepressant medications.[11]

- A person with hoarding disorder may be prescribed an antidepressant medication in the SSRI class. Common examples in this category include Paxil and Prozac. SSRI medications may help alleviate some of the anxiety about not having what you need when you need it, which is one of the core elements of the condition.

Getting or Giving Support

-

1Be patient and understanding. Hoarding is hard to accept and hard to treat. It is never as simple as just clearing out lots of “junk.” If you have the disorder, try to understand that the people who care about you are trying to help, not trying to “steal” or “take away” things you need. If you are trying to help someone with the disorder, plan for the “long haul” and be ready for setbacks.[12]

- Ask questions of a person who has hoarding disorder in order to better understand him or her, not to judge. Ask “Why do you feel like you need all of these?”, not “What in the world could you ever need all this junk for?”

-

2Set positive, step-by-step goals. Whether you are the person who has hoarding disorder or the person helping the person who has hoarding disorder, it is important to set up small, manageable goals as steps toward reaching more lasting improvements. Treating hoarding disorder involves changing how a person views the world, and such elemental changes don’t tend to happen all at once.[13]

- Once you get to the point where you can begin de-cluttering, focus on one room at a time, or one category of hoarded item at a time. Start with less essential areas of the house or item categories. Celebrate achievements, however small.

-

3Find support groups. People who have hoarding disorder need the help of professionals and family and friends in order to recognize and begin dealing with the problem. However, sometimes they need to be able to interact with other people who truly understand what they are going through. This is particularly true since people who have hoarding disorder tend to experience severe social isolation, both actual and perceived.[14]

- As awareness of hoarding disorder grows, so too do support group options. There is a good chance that there is a meeting somewhere in your area. If not, online support groups can also be very helpful.

- Physicians, mental health professionals, social workers, and local nonprofit or government agencies that deal with hoarding disorder can often provide guidance on support groups available to you or the person who has hoarding disorder in your life.

-

4Consider more confrontational options carefully. Treating hoarding disorder works best when the person with the condition is actively and positively involved. Sometimes, though, your concern for the person’s health or safety may need to trump his or her lack of support for the effort. Try your best to convince the person who has hoarding disorder to “get on board” with treatment before considering other options.[15]

- While they make for good TV, interventions usually provide only a short-term fix for hoarding disorder. If underlying causes and perspectives are not addressed, whatever clutter is cleared after a person is put “on the spot” is likely to return quickly.

- Sadly, people have died due to hoarding disorder, by contracting illnesses from rodent infestations or even by being buried under fallen piles of clutter. Some people who have hoarding disorder live in homes so cluttered that they cannot access sinks, toilets, windows, or even doors. If you genuinely fear for the health and safety of a person who has hoarding disorder, call the proper authorities — the fire department, police, social services, child services, animal control (for pet hoarding), etc.[16]

References

- ↑ https://www.adaa.org/sites/default/files/Steketee_Master-Clinician.pdf

- ↑ https://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd/hoarding-basics

- ↑ https://hoarding.iocdf.org/about-hoarding/is-it-hoarding-clutter-collecting-or-squalor/

- ↑ https://www.adaa.org/sites/default/files/Steketee_Master-Clinician.pdf

- ↑ https://www.adaa.org/sites/default/files/Steketee_Master-Clinician.pdf

- ↑ http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/hoarding/Pages/Introduction.aspx#treatment

- ↑ https://www.apa.org/monitor/2020/04/ce-corner-hoarding

- ↑ https://www.adaa.org/sites/default/files/Steketee_Master-Clinician.pdf

- ↑ http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/hoarding/Pages/Introduction.aspx#treatment

- ↑ https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/hoarding-disorder/what-is-hoarding-disorder#section_3

- ↑ https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/hoarding-disorder/what-is-hoarding-disorder#section_3

- ↑ https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/hoarding/helping-someone-who-hoards/

- ↑ https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/hoarding/helping-someone-who-hoards/

- ↑ https://hoarding.iocdf.org/supportgroups/

- ↑ https://www.helpguide.org/articles/anxiety/helping-someone-with-hoarding-disorder.htm

- ↑ https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17682-hoarding-disorder

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...