This article was co-authored by Gerald Posner. Gerald Posner is an Author & Journalist based in Miami, Florida. With over 35 years of experience, he specializes in investigative journalism, nonfiction books, and editorials. He holds a law degree from UC College of the Law, San Francisco, and a BA in Political Science from the University of California-Berkeley. He’s the author of thirteen books, including several New York Times bestsellers, the winner of the Florida Book Award for General Nonfiction, and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History. He was also shortlisted for the Best Business Book of 2020 by the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing.

This article has been viewed 83,228 times.

While “soft news” articles (such as interviews, human interest stories, and reviews) offer the writer more flexibility with structure and personal opinion, “hard news” articles follow a precise formula. Known as the “inverted pyramid,” this formula is designed to get right to the point. By sticking to the bare facts of your story, prioritizing those that are most important, and using your quotes effectively, you can inform your readers of what happened even if they don’t finish reading your article. With a little practice, organizing your material to fit this formula can become second nature.

Steps

Structuring Your Story

-

1Organize your material according to the “inverted pyramid.” Assume that your reader will quit reading before they reach the end of your story. Load the beginning of your article with the most essential facts so they still get the gist of it. Imagine a pyramid flipped upside down, with its widest part is on top. Aim to fill that space with all of the essentials, and then taper off with less relevant info as you reach the narrowest point at the bottom.[1]

- The inverted pyramid is especially important for online content, since its readers are less likely to read a story in full. Also, having the most relevant information at the beginning increases the story’s chances of popping in keyword searches.

- This technique is also referred as “front-loading.”

-

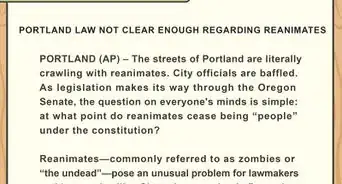

2Write a strong lead. Aim to hook your audience into reading further. At the same time, provide them with a condensed version of the story right up front in case they move on. Include the five W’s and one H in your first paragraph: who, what, when, where, why, and how. To present the essence of the story all at once, address them all in the very first sentence (known as the “summary” or “hard news” lead). To tantalize the reader into reading more, experiment by breaking them up over the first and second.[2]

- Summary lead: “More than 200 firefighters fought a six-alarm fire that destroyed 36 homes and six businesses on Myrtle Avenue in the Ridgewood section of Queens late Sunday night.”

- Experimental lead: “Residents of Queens watched on in horror as more than 200 firefighters fought a six-alarm blaze in Ridgewood late Sunday night. The fire tore through six buildings along Myrtle Avenue, destroying a half-dozen businesses and 36 overhead apartments.”

- ”Leads” may also be spelled as “ledes” in the news industry.[3]

Advertisement -

3Give more background after the lead. Use your first paragraph to provide the most basic info. From there, flesh out the story in more detail. Continue presenting the facts in order of the most relevant. For example:[4]

- "What began as a grease fire in the kitchen of Tony’s Restaurant at 1411 Myrtle Ave quickly spread to neighboring buildings due to Sunday’s high winds."

- "The M train’s elevated tracks along this stretch of Myrtle Ave further impeded firefighters’ ability to access the burning rooftops."

- "The NYFD evacuated the entire block immediately upon arrival in case the blaze spread any further."

-

4Include a quote early on. Give your reader someone to relate to. Introduce a witness or source within the first few paragraphs. Continue to pepper your story with the voices of people who played a part in and/or were directly affected by its events. For example:[5]

- “'I just got home from work and went straight to bed,' said Maria Sanchez, resident of 1421 Myrtle. 'Then all of a sudden my husband’s shaking me back awake and saying that the whole block is burning down.'”

- “'This is the worst fire this neighborhood has had in some time,' said Fire Commissioner Joseph Hernandez."

-

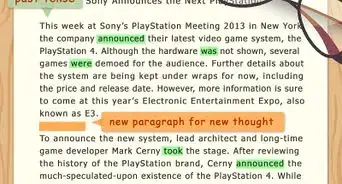

5Write short paragraphs. Remember that your reader is likely to skim the article before deciding on whether or not they will read it. Make your text easy to skim by avoiding long paragraphs. Stick to a maximum of two sentences each, or even just a single sentence.[6]

- To further avoid large blocks of text, keep your sentences short as well. Use 30 words or less per sentence. Rewrite any dependent clauses so that each one becomes its own sentence.[7]

- Paragraphs may be referred to as “graphs” in news reporting.

-

6Finish with interesting but inessential info. Conclude your article with a quote or angle that fleshes the story out a little bit more. However, make sure that this info isn’t critical for the reader to know in order to understand the whole story. Expect the very end of your article to be cut to save space if need be.

- Reread the whole article, minus your last couple of paragraphs, to verify that it still makes sense without the additional info.

- If key information is lost, rewrite the article to include that information toward the beginning.

- An example of a fitting end that could be cut if needed: “‘My brother’s been letting me crash here with him after my last landlord sold my old building to developers,’ said Brian Guiliano, 27, whose brother, Vincent, lately resided right next-door to Tony’s Restaurant. ‘I don’t know where I’m supposed to go now.’”

Quoting and Attributing Sources Correctly

-

1Have each quote stand by itself. Structure each one as its own sentence. Avoid using a partial quote as a building block for one of your own sentences. Allow the quote to speak for itself, rather than explaining what the speaker meant by it. [8]

- Good example: “This was one of the worst I’ve ever seen,” said Richard Sloan, firefighter.

- Bad example: The six-alarm fire was “one of the worst I’ve ever seen,” said Richard Sloan, firefighter.

-

2Aim for accuracy. When possible, use the speaker’s exact words as spoken. Refrain from editing grammar. If their original quote is structured in a way that makes it hard for the reader to understand, make your edits visible. Use ellipses to mark where original content has been cut. If you need to substitute one word for another in order to clarify the context, bracket your substitutions to show that these are your words, not the speaker’s.[9]

- For example, say that your original quote reads, “I only had my underwear on. I was just sitting there watching TV. Then the firemen started knocking on doors. When they knocked on mine, they, you know, they told me not to waste time, just come now, so I ran out in just that. Some kind lady on the street saw me, ran home, brought me back her bathrobe.”

- Now say that, due to space, you only want to use: “When they knocked on mine, they, you know, they told me not to waste time, just come now, so I ran out in just that. Some kind lady on the street saw me, ran home, brought me back her bathrobe.”

- Edit the quote so it reads: “When [the firemen] knocked on [my door], they … told me not to waste time, just come now, so I ran out in just [my underwear]. Some kind lady on the street saw me, ran home, brought me back her bathrobe.”

-

3Know when to paraphrase. Use direct quotes only to spice up your story with unique observations, rather than rely on them to establish basic facts. If a quote provides only the fundamentals of the story (like the five W’s and one H), paraphrase it into a sentence of your own, then attribute it to its source. Omit quotation marks for paraphrased quotes.[10]

- A good direct quote: “One second it was just Tony’s on fire. Then it was like I just blinked and then whoosh, all the other buildings were up in flames, too,” said Brianna Johnson, neighbor.

- A quote that should be paraphrased: “The fire spread quickly because of last night’s high winds,” said Fire Commissioner Joesph Hernandez.

- A paraphrased quote: Sunday night’s high winds caused the fire to spread swiftly, said Fire Commissioner Joesph Hernandez.

-

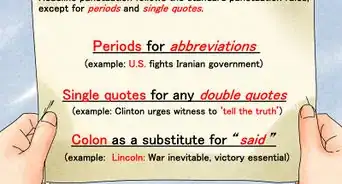

4Use neutral terminology. When quoting a source directly, stick with the verb “said.” Understand that a hard news article should aim to be objective in its presentation of the facts. With that in mind, expect most synonyms for the word “said” to suggest that the speaker is doing more than simply making a statement. Let the speaker’s words speak for themselves, rather than define them further with more specific verbs.[11]

- Synonyms to avoid include: admit, announce, argue, claim, declare, insist, promise, pronounce, reply, retort, shout, and vow.

- Use the term “according to” if your source agrees to provide information, but refuses to be quoted.

- Also use “according to” when referencing documents.

-

5Cite sources. Always identify the speaker when using direct or paraphrased quotes. Additionally, cite your source for any new information that hasn’t already been reported.[12] If your source wishes to remain unidentified, you should still attribute their info to “an anonymous source.”

- If you attribute multiple pieces of info to one source, include their full name plus any relevant title the first time you mention them (“Fire Commissioner Joesph Hernandez”). After that, only use their last name (“Hernandez”) and the appropriate prefix (here, “Mr.”) if required. Some news outlets may prefer using the last name without a prefix.

- When composing a paragraph, avoid sticking other material in between two pieces of info from a single source. Doing so will force you to cite your source twice in one paragraph, which will sound repetitive.

- The only times you do not need to attribute information to a direct source are: if you yourself are an eyewitness; if you are able to prove that the info is true; if the info is already public knowledge; or if three other publications have already reported it to be true.

Practicing the Hard News Style

-

1Write your own leads to other writers’ stories. Ask someone to cut-and-paste all but the lead paragraph of an online story into a new word document, or have them clip the lead graph out of a newspaper. Read the remainder of the story and glean as many details as you can. Using those, write your own lead with the aim of condensing the most important facts into one or two sentences. After that, read the original lead to see how well yours measures up to it.[13]

- If the original writer followed the inverted pyramid, there may be info in the original lead that isn’t repeated in the text that you read. Don’t worry if your lead doesn’t include that precise info. Compare your lead to the original only to see how well each one summarizes the text that follows.

-

2Maintain a neutral voice. Remember that hard news aims to report the bare facts objectively, nothing more.[14] To practice objectivity, cover an event that touches on a subject that you feel passionate about (such as a presidential debate or football game in which you strongly favor one side over the other). Write an article about it. Then have someone read it and/or proofread it yourself to spot any instances where your personal opinion shows itself.

- Look for adjectives and verbs that overstate what actually happened. For example, describing your favorite quarterback’s performance as “amazing” is unwarranted if all of their plays went by the book.

- Watch out for words with loaded meanings that suggest bias. For instance, if you are writing about a crime, avoid using terms like “thug” to describe the perpetrator, since this implies a judgment on your part.

- Check to see if you have represented all sides fairly. If you are covering a political debate, for example, make sure you haven’t just highlighted all of your favorite candidate’s high points and all of their opponent’s low points.

-

3Use as few words as possible. Proofread your article (or even pieces by other writers’) to identify any words or sentences that could be cut without losing the story’s essence. If possible, rephrase necessary facts that could be described in a single word. Shift impressive but unnecessary details toward the end, where they can be cut by editors if necessary without upsetting the article’s flow.[15]

- Use active verbs instead of passive ones. For example, “The candidate visits New York today,” instead of, “The candidate is visiting New York today.”

- Identify clunky word structure and run-on sentences by reading the article out loud.

- Use Twitter or the word-count feature to train yourself to write short, crisp sentences.[16]

Expert Q&A

-

QuestionHow do you write a good news article?

Gerald PosnerGerald Posner is an Author & Journalist based in Miami, Florida. With over 35 years of experience, he specializes in investigative journalism, nonfiction books, and editorials. He holds a law degree from UC College of the Law, San Francisco, and a BA in Political Science from the University of California-Berkeley. He’s the author of thirteen books, including several New York Times bestsellers, the winner of the Florida Book Award for General Nonfiction, and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History. He was also shortlisted for the Best Business Book of 2020 by the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing.

Gerald PosnerGerald Posner is an Author & Journalist based in Miami, Florida. With over 35 years of experience, he specializes in investigative journalism, nonfiction books, and editorials. He holds a law degree from UC College of the Law, San Francisco, and a BA in Political Science from the University of California-Berkeley. He’s the author of thirteen books, including several New York Times bestsellers, the winner of the Florida Book Award for General Nonfiction, and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History. He was also shortlisted for the Best Business Book of 2020 by the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing.

Author & Journalist The key is balancing speed and credibility—you want to write your article as quickly and as accurately as possible. These two factors often work against each other, since you need to consult multiple sources in order to get your facts nailed down.

The key is balancing speed and credibility—you want to write your article as quickly and as accurately as possible. These two factors often work against each other, since you need to consult multiple sources in order to get your facts nailed down. -

QuestionAre soft new and feature stories different?

DonaganTop AnswererYes. "Soft news" describes current or recent events of a "soft" nature. "Feature stories" will touch on events or conditions that may or may not be current or recent.

DonaganTop AnswererYes. "Soft news" describes current or recent events of a "soft" nature. "Feature stories" will touch on events or conditions that may or may not be current or recent.

Expert Interview

Thanks for reading our article! If you'd like to learn more about writing an article, check out our in-depth interview with Gerald Posner.

References

- ↑ https://www.csun.edu/~bashforth/406_PDF/406_Essay3/HardNewsVSFeatureStories.pdf

- ↑ https://www.csun.edu/~bashforth/406_PDF/406_Essay3/HardNewsVSFeatureStories.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/

- ↑ https://www.csun.edu/~bashforth/406_PDF/406_Essay3/HardNewsVSFeatureStories.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/

- ↑ https://www.csun.edu/~bashforth/406_PDF/406_Essay3/HardNewsVSFeatureStories.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/

- ↑ http://spcollege.libguides.com/c.php?g=254319&p=1695313

- ↑ http://www.ck12.org/book/Journalism-101/section/2.2/