1728 Musin Rebellion

The 1728 Musin Rebellion also known as Yi In-jwa's Rebellion was an unsuccessful seventeen-day rebellion against King Yeongjo of the Joseon Dynasty in Korea on May 1728.[1] At that time, anonymous posters appeared in Jeonju and Namwon claiming that King Gyeongjong's death in early October 1724 was due to poisoning by the man who had become King Yeongjo. Two men, Sim Yu-hyeon and Bak Mi-gwi stole gunpowder from a magazine to blow up the Hong-hua and Don-hua gates. Initially the revolt was concentrated in Jeolla province.[2] "During three weeks of fighting the government lost control of thirteen county seats, and the rebels drew great support from people in Kyŏnggi, North Ch’ungch’ŏng, South Ch’ungch’ŏng, and South Kyŏngsang Provinces."[3]

| 1728 Musin Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

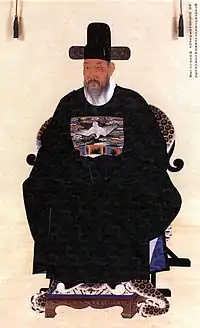

Portrait of Oh Myeong-Hang | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| More than 70,000 | Five Guards Command: 2300 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Annihilation | Moderate | ||||||

| 1728 Musin Rebellion | |

| Hangul | 무신란 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 戊申亂 |

| Revised Romanization | Musinran |

| McCune–Reischauer | Mushinran |

Name

Yi In-jwa-Chung Hee-Ryang's Rebellion (李麟佐ㅡ鄭希亮ㅡ亂) is a name that reflects the regional leaders, Jeong Hee-Ryang, and General Yi In-jwa (이인좌).

Background

During the reign of Sukjong, extremist members of the Namin (Southerners), Chunso, and Soron (Young Disciples) factions fought over whether Prince Gyeongjong or his younger half-brother Yeongjo was the most suitable heir to the throne. Yeongjo rose to the throne when Gyeongjong died, causing more bloody conflicts between the factions. In 1727, Yeongjo removed the Noron (Old Disciples) from power and replaced them with the Soron as his attempt to mollify the factionalism that once affected his brother's court. However, the expelled Soron members occupied military and civil posts in the capital and provinces.[4]

Preparation

Over three years, the rebels built up an underground organization committed to overthrowing and destroying the Noron faction and placing relatives of Yongjo on the throne. They were also aided by a small group of fifth-columnists who were plotting against Yŏngjo from within the government, which meant that Soron rebels were plotting to overthrow their comrades.

The rebels planned a disturbance in a strategic location near Hanya. Two men, Sim Yu-hyeon and Bak Mi-gwi stole gunpowder from a magazine to blow up the Hong-hua and Don-hua gates. ng. The rebels posted anonymous posters in Jeonju and Namwon, claiming that King Gyeongjong's death in early October 1724 was due to poisoning by the man who had become King Yeongjo.

Leaders during the Rebellion

Rebels

Yi In-jwa Kyongsang and Ch'ungch'ong Provinces Southerner faction

Yi Ung-bo Kyongsang and Ch'ungch'ong Provinces Southerner faction

Park Pil-Hyeong Kyongsang Province Disciples faction extremist

Yi Sasong Kyonggi Province Disciples faction

Jeong Hee-Ryeong Kyongsang Province Southerner faction

Park Pil-mong Kyonggi Province Disciples faction extremist

Nam Tae-Jing Disciples faction extremist

Min Kwan-hyeo Capital, Kyonggi and Ch'ungch'ong Provinces Southerner faction

Government Officials

Oh Myeong-Hang

Rebellion

The original fomentation of the revolt was concentrated in Jeolla province.[5] "During three weeks of fighting the government lost control of thirteen county seats, and the rebels drew great support from people in Kyŏnggi, North Ch'ungch'ŏng, South Ch'ungch'ŏng, and South Kyŏngsang Provinces."[6] The rebellion raged for three weeks and the government control of four county seats to the rebels in Ch'ungch'ong, four and five in southern Kyongsang Provinces led by province elites and followed an unsuccessful attempt to mobilize Andong. The seizures of provincial towns were a prelude to capturing the capital. The rebels seized regional seats to arm themselves before launching a coordinated attack on the capital. But this did not go to plan. Rebel fifth-columnists led by P'yongan commander Yi Sasong (李v思蔑,?-1728) were supposed to mobilize troops under their command and to use the crisis provided to take the capital. The captured rebels betrayed fifth columnists, neutralized by the court, raising a force to suppress the rebels in the provinces.

Rebels in Ch'ongju marched towards the capital but were in battles in Kyonggi Province; unaware of the defeat of their comrades, the Kyongsang province rebels made further attempts to head north to link with rebel forces but were hemmed in by inhospitable terrain and government troops, and were eventually crushed.

First, Yi In-jwa attacked Cheongju and General Yi Bong-sang. The gist of the passage is that Gyeongjong's death is not natural, but poisoning by Yeongjo and Noron, and Yeongjo) is not a prince of Sukjong, It was about repaying the royal family and establishing Tan (坦) of Milpunggun, the son of Crown Prince Sohyeon (嫡派孫), as king. All the soldiers wore white robes like mourning to mourn King Gyeongjong, and met Pyeongan General Yi Sa-seong, Commander Kim Jung - gi, Nam Tae -jing , etc.

However, Choi Gyu-seo, the elder of Soron, who was moving out of Yongin , filed a complaint with the court, and the plan of the rebels collapsed. Myeong-hang Oh, the military officer appointed to ) The rebellion was suppressed after only three months by the government forces of 吳命恒. They numbered only 2,300, but they quickly slaughtered the rebels, who were numerous but lost their actual armed forces.

Although it was a short-lived rebellion, the numbers were so, and the local army, before the rebel army's yangbans were conciliated, could not suppress it, so the situation in Jincheon, Juksan, Anseong, etc. It was in danger, and the masterminds of the rebellion, including Lee In-jwa, were transported to Seoul and executed. The Milpung army was also killed (there is a theory that he committed suicide).

The Rebellion of Yi In-jwa, which ended on the 6th, resulted in the alienation of the Yeongnam region from the politics of the late Joseon Dynasty. Although Geobyeongji was Cheongju, Yeongnam, the hometown of southerners, produced the most mockers and sympathizers. In other words, except for the high priests of some regions, such as Andong, most of them sympathized with the Geosa.

Lee In-jwa was the son-in-law of Yun -hyeok, a man, and was supported by Yurim in Yeongnam.

After the rebellion was settled, Yeongjo built the Pyeongyeong Nambi (平嶺南碑) outside the south gate of Daegu-bu and nailed Yeongnam to the rebellion.

Aftermath

On the twenty-second of the fourth month, some three weeks after leaders had been executed, Yongjo delivered a mandate to was part of the court's post-Rebellion analysis, which attempted to determine its causes and the rebels' there would be no repetition. Notable on this list is a made about a single region — Yongnam or northern Province - and its connections to the rebellion: In the middle of the night, when I'm lying down in the palace, and I start thinking about Yongnam, my heart grows so heavy that I can't get back to sleep. Considering that the rebels seized territory and mobilized in four different provinces, it is curious that Yongjo lost sleep about Kyongsang but not Ch'ungch'ong, Cholla, or Kyonggi Provinces.

Soron (Wanron) did a great job in suppressing this rebellion. However, since most of the instigators of this rebellion were also hard-liners (Junron) of Soron, the power of Soron was severely damaged by this rebellion, and Noron mostly took over the government. Over the next 50 years, people in Gyeongsang -do, except for Andong, were not allowed to take the exam in the past, and Cho- shik's servants, had no intention of going on to the post. [2] The ban continued until the overthrow of Daewongun 130 years later because the wage did not mark the candidates who passed the written test even after they were allowed to apply in the past.

Bibliography

- Cho, Ch’anyong [조찬용]. 2003, 1728 nyŏn Musinsat’ae koch’al. [1728년 무신사태 고찰/An enquiry into the 1728 Musillan situation], Seoul: iolive

- Jackson, Andrew David. 2011, The 1728 Musillan Rebellion: Resources and the Fifth-Columnists, Unpublished PhD dissertation. University of London

- Jackson, Andrew David. 2016, The 1728 Musin Rebellion: Politics and Plotting in Eighteenth-Century Korea, University of Hawaii Press

- Oh, Gap-Kyun [오갑균]. 1977, "英祖朝 戊申亂에 관한 考察. On the Musin(戊申)-Revolt under the Reign of King Youngcho," 역사교육 21 (5): 65-99 (in Korean)

References

- Jackson, Andrew David. 2016, The 1728 Musin Rebellion: Politics and Plotting in Eighteenth-Century Korea, pg 2

- Byun, Ju Seunng and Gyeong Deuk Mun. 2013. "18세기 전라도 지역 무신란(戊申亂)의 전개과정 The Development of Musin Revolt(戊申亂) in Jeolla Province in the 18th Century - Focused on 'the investigation record of the Musin Revolt(「戊申逆獄推案」),'"인문과학연구 93: 135-178 [in Korean]

- Jackson, Andrew David (2013). "THE 1728 MUSIN REBELLION (MUSILLAN 戊申亂): APPROACHES, SOURCES AND QUESTIONS". Studia UBB Philologia. 58 (1): 161–172 [162].

- Jackson, Andrew David (2013). "The initiation of the 1728 Musin rebellion: Assurances, The Fifth-Columnists and Military Resources". Korean Histories. 3 (2): 3–15.

- Byun, Ju Seunng and Gyeong Deuk Mun. 2013. "18세기 전라도 지역 무신란(戊申亂)의 전개과정 The Development of Musin Revolt(戊申亂) in Jeolla Province in the 18th Century - Focused on 'the investigation record of the Musin Revolt(「戊申逆獄推案」),'" "인문과학연구" 93: 135-178 [in Korean]

- Jackson, Andrew David (2013). "THE 1728 MUSIN REBELLION (MUSILLAN 戊申亂): APPROACHES, SOURCES AND QUESTIONS". Studia UBB Philologia. 58 (1): 161–172 [162].