Healthcare in the United States

Healthcare in the United States is largely provided by private sector healthcare facilities, and paid for by a combination of public programs, private insurance, and out-of-pocket payments. The U.S. is the only developed country without a system of universal healthcare, and a significant proportion of its population lacks health insurance.[1][2][3][4]

| Health care in the United States |

|---|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Healthcare reform in the United States |

|---|

|

|

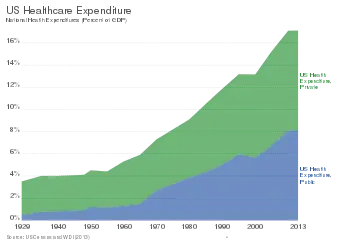

The United States spends more on healthcare than any other country, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP.[1] However, this expenditure does not necessarily translate into better overall health outcomes compared to other developed nations.[5] Coverage varies widely across the population, with certain groups, such as the elderly and low-income individuals, receiving more comprehensive care through government programs such as Medicaid and Medicare.

The U.S. healthcare system has been the subject of significant political debate and reform efforts, particularly in the areas of healthcare costs, insurance coverage, and the quality of care. Legislation such as the Affordable Care Act of 2010 has sought to address some of these issues, though challenges remain.

Uninsured rates have fluctuated over time, and disparities in access to care exist based on factors such as income, race, and geographical location.[6][7][8][9] The private insurance model predominates, and employer-sponsored insurance is a common way for individuals to obtain coverage.[1][10][11] The complex nature of the system, as well as its high costs, has led to ongoing discussions about the future of healthcare in the United States.

At the same time, the United States is a global leader in medical innovation, measured either in terms of revenue or the number of new drugs and devices introduced.[12][13] The Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity concluded that the United States dominates science & technology, which "was on full display during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the U.S. government [delivered] coronavirus vaccines far faster than anyone had ever done before," but lags behind in fiscal sustainability, with "[government] spending [...] growing at an unsustainable rate."[14]

History

The healthcare system in the United States can be traced back to the Colonial Era.[15] Community-oriented care was typical, with families and neighbors providing assistance to the sick.[16][17]

During the 19th century, the practice of medicine began to professionalize. The establishment of medical schools and professional organizations led to standardized training and certification processes for doctors.[18] Despite this progress, healthcare services remained disparate, particularly between urban and rural areas. The concept of hospitals as institutions for the sick began to take root, leading to the foundation of many public and private hospitals.[19]

In the early 20th century, advances in medical technology and a focus on public health contributed to a shift in healthcare.[20] The American Medical Association (AMA) worked to standardize medical education, and the introduction of employer-sponsored insurance plans marked the beginning of the modern health insurance system.[21]

The post-World War II era saw a significant expansion in healthcare. The passage of the Hill-Burton Act in 1946 provided federal funding for hospital construction, and Medicare and Medicaid were established in 1965 to provide healthcare coverage to the elderly and low-income populations, respectively.[22][23]

The latter part of the 20th century saw continued evolution in healthcare policy, technology, and delivery. Following the Stabilization Act of 1942, employers, unable to provide higher salaries to attract or retain employees, began to offer insurance plans, including healthcare packages, as a benefit in kind, thereby beginning the practice of employer-sponsored health insurance.[24] The Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973 encouraged the development of managed care, while advances in medical technology revolutionized treatment. In the 21st century, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010, extending healthcare coverage to millions of uninsured Americans and implementing reforms aimed at improving quality and reducing costs.[25]

Statistics

Hospitalizations

According to a statistical brief by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), there were 35.7 million hospitalizations in 2016,[26] a significant decrease from the 38.6 million in 2011.[27] For every 1,000 in the population, there was an average of 104.2 stays and each stay averaged $11,700 (equivalent to $14,266 in 2022[28]),[26] an increase from the $10,400 (equivalent to $13,257 in 2022[28]) cost per stay in 2012.[29] 7.6% of the population had overnight stays in 2017,[30] each stay lasting an average of 4.6 days.[26]

A study by the National Institutes of Health reported that the lifetime per capita expenditure at birth, using the year 2000 dollars, showed a large difference between the healthcare costs of females ($361,192, equivalent to $613,782 in 2022[28]) and males ($268,679, equivalent to $456,573 in 2022[28]). A large portion of this cost difference is in the shorter lifespan of men, but, even after adjustment for age (assuming men live as long as women), there still is a 20% difference in lifetime healthcare expenditures.[31]

Health insurance and accessibility

.JPG.webp)

Unlike most developed nations, the US health system does not provide healthcare to the country's entire population.[32] Instead, most citizens are covered by a combination of private insurance and various federal and state programs.[33] As of 2017, health insurance was most commonly acquired through a group plan tied to an employer, covering 150 million people.[34] Other major sources include Medicaid, covering 70 million, Medicare, 50 million, and health insurance marketplaces created by the ACA covering around 17 million.[34] In 2017, a study found that 73% of plans on ACA marketplaces had narrow networks, limiting access and choice in providers.[34]

Healthcare coverage is provided through a combination of private health insurance and public health coverage (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid). In 2013, 64% of health spending was paid for by the government,[35][36] and funded via programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program, Tricare, and the Veterans Health Administration. People aged under 65 acquire insurance via their or a family member's employer, by purchasing health insurance on their own, getting government and/or other assistance based on income or another condition, or are uninsured. Health insurance for public sector employees is primarily provided by the government in its role as employer.[37] Managed care, where payers use various techniques intended to improve quality and limit cost, has become ubiquitous.

Measures of accessibility and affordability tracked by national health surveys include: percent of population with insurance, having a usual source of medical care, visiting the dentist yearly, rates of preventable hospitalizations, reported difficulty seeing a specialist, delaying care due to cost, and rates of health insurance coverage.[38] In 2004, an OECD report noted that "all OECD countries [except Mexico, Turkey, and the US] had achieved universal or near-universal (at least 98.4% insured) coverage of their populations by 1990".[39] The 2004 IOM report also observed that "lack of health insurance causes roughly 18,000 unnecessary deaths every year in the US".[32] A 2009 study done at Harvard Medical School with Cambridge Health Alliance by cofounders of Physicians for a National Health Program, a pro-single payer lobbying group, showed that nearly 45,000 annual deaths are associated with a lack of patient health insurance. The study also found that uninsured, working Americans have an approximately 40% higher mortality risk compared to privately insured working Americans.[40]

The Gallup organization tracks the percent of adult Americans who are uninsured for healthcare, beginning in 2008. The rate of uninsured peaked at 18.0% in 2013 prior to the ACA mandate, fell to 10.9% in the third quarter of 2016, and stood at 13.7% in the fourth quarter of 2018.[41] "The 2.8-percentage-point increase since that low represents a net increase of about seven million adults without health insurance."[41]

The US Census Bureau reported that 28.5 million people (8.8%) did not have health insurance in 2017,[42] down from 49.9 million (16.3%) in 2010.[44] Between 2004 and 2013, a trend of high rates of underinsurance and wage stagnation contributed to a healthcare consumption decline for low-income Americans.[45] This trend was reversed after the implementation of the major provisions of the ACA in 2014.[46]

As of 2017, the possibility that the ACA may be repealed or replaced has intensified interest in the questions of whether and how health insurance coverage affects health and mortality.[48] Several studies have indicated that there is an association with expansion of the ACA and factors associated with better health outcomes such as having a regular source of care and the ability to afford care.[48] A 2016 study concluded that an approximately 60% increased ability to afford care can be attributed to Medicaid expansion provisions enacted by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.[49] Additionally, an analysis of changes in mortality post Medicaid expansion suggests that Medicaid saves lives at a relatively more cost effective rate of a societal cost of $327,000 to $867,000 (equivalent to $398,730 to $1.06 million in 2022[28]) per life saved compared to other public policies which cost an average of $7.6 million (equivalent to $9.27 million in 2022[28]) per life.[50]

A 2009 study in five states found that medical debt contributed to 46.2% of all personal bankruptcies, and 62.1% of bankruptcy filers claimed high medical expenses in 2007.[51] Since then, health costs and the numbers of uninsured and underinsured have increased.[52] A 2013 study found that about 25% of all senior citizens declare bankruptcy due to medical expenses.[53]

In practice, the uninsured are often treated, but the cost is covered through taxes and other fees which shift the cost.[54] Forgone medical care due to extensive cost sharing may ultimately increase costs due to downstream medical issues; this dynamic may play a part in US's international ranking as having the highest healthcare expenditures despite significant patient cost-sharing.[46]

Those who are insured may be underinsured such that they cannot afford adequate medical care. A 2003 study estimated that 16 million US adults were underinsured, disproportionately affecting those with lower incomes—73% of the underinsured in the study population had annual incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level.[55] Lack of insurance or higher cost sharing (user fees for the patient with insurance) create barriers to accessing healthcare: use of care declines with increasing patient cost-sharing obligation.[46] Before the ACA passed in 2014, 39% of below-average income Americans reported forgoing seeing a doctor for a medical issue (whereas 7% of low-income Canadians and 1% of low-income British citizens reported the same).[56]

Health in the US in global context

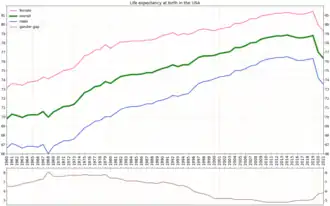

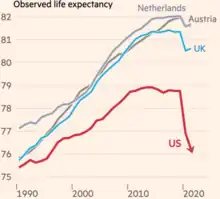

The US life expectancy is 78.6 years at birth, up from 75.2 years in 1990; this ranks 42nd among 224 nations, and 22nd out of the 35 OECD countries, down from 20th in 1990.[59][60]

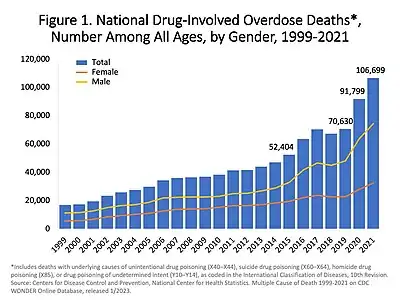

In 2021, US life expectancy fell to 76.4 years, the shortest in roughly two decades. Drivers for this drop in life expectancy include accidents, drug overdoses, heart and liver disease, suicides and the COVID-19 pandemic.[61]

In 2019, the under-five child mortality rate was 6.5 deaths per 1000 live births, placing the US 33rd of 37 OECD countries.[62] In 2010–2012, more than 57,000 infants (52%) and children under 18 years died in the US.[63]

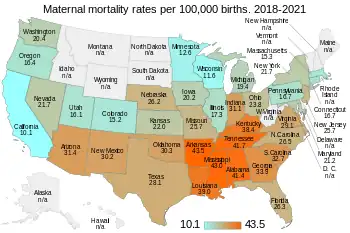

While not as high in 2015 (14)[64] as in 2013 (18.5), maternal deaths related to childbirth have shown recent increases; in 1987, the mortality ratio was 7.2 per 100,000.[65] As of 2015, the US rate is double the maternal mortality rate in Belgium or Canada, and more than triple the rate in the Finland as well as several other Western European countries.[64] In 2019, Black maternal health advocate and Parents writer Christine Michel Carter interviewed Vice President Kamala Harris. As a senator, in 2019 Harris reintroduced the Maternal Care Access and Reducing Emergencies (CARE) Act which aimed to address the maternal mortality disparity faced by women of color by training providers on recognizing implicit racial bias and its impact on care. Harris stated:

"We need to speak the uncomfortable truth that women—and especially Black women—are too often not listened to or taken seriously by the health care system, and therefore they are denied the dignity that they deserve. And we need to speak this truth because today, the United States is 1 of only 13 countries in the world where the rate of maternal mortality is worse than it was 25 years ago. That risk is even higher for Black women, who are three to four times more likely than white women to die from pregnancy-related causes. These numbers are simply outrageous."

Life expectancy at birth for a child born in the US in 2015 is 81.2 (females) or 76.3 (males) years.[66] According to the WHO, life expectancy in the US is 31st in the world (out of 183 countries) as of 2015.[67] The US's average life expectancy (both sexes) is just over 79.[67] Japan ranks first with an average life expectancy of nearly 84 years. The US ranks lower (36th) when considering health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) at just over 69 years.[67] Another source, the Central Intelligence Agency, indicates life expectancy at birth in the US is 79.8, ranking it 42nd in the world. Monaco is first on this list of 224, with an average life expectancy of 89.5.[68]

A 2013 National Research Council study stated that, when considered as one of 17 high-income countries, the US was at or near the top in infant mortality, heart and lung disease, sexually transmitted infections, adolescent pregnancies, injuries, homicides, and rates of disability. Together, such issues place the US at the bottom of the list for life expectancy in high-income countries.[69] Females born in the US in 2015 have a life expectancy of 81.6 years, and males 76.9 years; more than three years less and as much as over five years less than people born in Switzerland (85.3 F, 81.3 M) or Japan (86.8 F, 80.5 M) in 2015.[66]

Causes of mortality in the US

The top three causes of death among both sexes and all ages in the US have consistently remained cardiovascular diseases (ranked 1st), neoplasms (2nd) and neurological disorders (3rd), since the 1990s.[70] In 2015, the total number of deaths by heart disease was 633,842, by cancer it was 595,930, and from chronic lower respiratory disease it was 155,041.[71] In 2015, 267.18 deaths per 100,000 people were caused by cardiovascular diseases, 204.63 by neoplasms and 100.66 by neurological disorders.[70] Diarrhea, lower respiratory, and other common infections were ranked sixth overall, but had the highest rate of infectious disease mortality in the US at 31.65 deaths per 100,000 people.[70] There is evidence, however, that a large proportion of health outcomes and early mortality can be attributed to factors other than communicable or non-communicable disease. As a 2013 National Research Council study concluded, more than half the men who die before the age of 50 die due to murder (19%), traffic accidents (18%), and other accidents (16%). For women, the percentages are different: 53% of women who die before the age of 50 die due to disease, whereas 38% die due to accidents, homicide, and suicide.[72] Diseases of despair (drug overdoses, alcoholic liver disease, and suicide), which started increasing in the early 1990s, kill roughly 158,000 Americans a year as of 2018.[73] Suicides reached record levels in the United States in 2022, with nearly 49,500 suicide deaths. Since 2011, around 540,000 people in the U.S. have died by suicide.[74][75] Cumulative poverty of ten years or more is the fourth leading risk factor for mortality in the United States annually.[76][77][78][79]

Since 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that the life expectancy for the US population was 77.0 years, a decrease of 1.8 years from 2019.[80] Life expectancy fell again in 2021 to 76.4 years, which has been attributed to COVID-19 and rising death rates from suicide, drug overdoses and liver disease.[81] Death certificate data from the CDC reveals that mortality rates among children and adolescents increased by 11% for the years 2019 and 2020 and a further 8% for 2020 and 2021, with injuries being a driving factor, along with homicide, suicide, drug overdoses and motor vehicle accidents impacting those aged 10 to 19.[82][83]

Providers

Healthcare providers in the US encompass individual healthcare personnel, healthcare facilities, and medical products.

Facilities

In the US, ownership of the healthcare system is mainly in private hands, though federal, state, county, and city governments also own certain facilities.

As of 2018, there were 5,534 registered hospitals in the US. There were 4,840 community hospitals, which are defined as nonfederal, short-term general, or specialty hospitals.[85] The nonprofit hospitals share of total hospital capacity has remained relatively stable (about 70%) for decades.[86] There are also privately owned for-profit hospitals as well as government hospitals in some locations, mainly owned by county and city governments. The Hill–Burton Act was passed in 1946, which provided federal funding for hospitals in exchange for treating poor patients.[87] The largest hospital system in 2016 by revenue was HCA Healthcare;[88] in 2019, Dignity Health and Catholic Health Initiatives merged into CommonSpirit Health to create the largest by revenue, spanning 21 states.[89]

Integrated delivery systems, where the provider and the insurer share the risk in an attempt to provide value-based healthcare, have grown in popularity.[90] Regional areas have separate healthcare markets, and in some markets competition is limited as the demand from the local population cannot support multiple hospitals.[91][92]

About two-thirds of doctors practice in small offices with less than seven physicians, with over 80% owned by physicians; these sometimes join groups such as independent practice associations to increase bargaining power.[93]

There is no nationwide system of government-owned medical facilities open to the general public but there are local government-owned medical facilities open to the general public. The US Department of Defense operates field hospitals as well as permanent hospitals via the Military Health System to provide military-funded care to active military personnel.[94]

The federal Veterans Health Administration operates VA hospitals open only to veterans, though veterans who seek medical care for conditions they did not receive while serving in the military are charged for services. The Indian Health Service (IHS) operates facilities open only to Native Americans from recognized tribes. These facilities, plus tribal facilities and privately contracted services funded by IHS to increase system capacity and capabilities, provide medical care to tribespeople beyond what can be paid for by any private insurance or other government programs.

Hospitals provide some outpatient care in their emergency rooms and specialty clinics, but primarily exist to provide inpatient care. Hospital emergency departments and urgent care centers are sources of sporadic problem-focused care. Surgicenters are examples of specialty clinics. Hospice services for the terminally ill who are expected to live six months or less are most commonly subsidized by charities and government. Prenatal, family planning, and dysplasia clinics are government-funded obstetric and gynecologic specialty clinics respectively, and are usually staffed by nurse practitioners. Services, particularly urgent-care services, may also be delivered remotely via telemedicine by providers such as Teladoc.

Besides government and private healthcare facilities, there are also 355 registered free clinics in the US that provide limited medical services. They are considered to be part of the social safety net for those who lack health insurance. Their services may range from more acute care (i.e., STDs, injuries, respiratory diseases) to long term care (i.e. dentistry, counseling).[95] Another component of the healthcare safety net would be federally funded community health centers.

Other healthcare facilities include long-term housing facilities which, as of 2019, there were 15,600 nursing homes across the US, with a large portion of that number being for-profit (69.3%)[96]

In 2022, 19 hospitals filed for bankruptcy, closed, or announced plans to close.[97]

Physicians (M.D. and D.O.)

Physicians in the US include those trained by the US medical education system, and those that are international medical graduates who have progressed through the necessary steps to acquire a medical license to practice in a state. This includes going through the three steps of the US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE). The first step of the USMLE tests whether medical students both understand and are capable of applying the basic scientific foundations to medicine after the second year of medical school. The topics include: anatomy, biochemistry, microbiology, pathology, pharmacology, physiology, behavioral sciences, nutrition, genetics, and aging. The second step is designed to test whether medical students can apply their medical skills and knowledge to actual clinical practice during students' fourth year of medical school. The third step is done after the first year of residency. It tests whether students can apply medical knowledge to the unsupervised practice of medicine.[98]

The American College of Physicians, uses the term "physician" to describe all medical practitioners holding a professional medical degree. In the US, the vast majority of physicians have a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree.[99] Those with Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.) degrees get similar training and go through the same MLE steps as MD's and so are also allowed to use the title "physician".

Medical products, research, and development

As in most other countries, the manufacture and production of pharmaceuticals and medical devices is carried out by private companies. The research and development of medical devices and pharmaceuticals is supported by both public and private sources of funding. In 2003, research and development expenditures were approximately $95 billion (equivalent to $136 billion in 2021[100]) with $40 billion (equivalent to $57.3 billion in 2021[100]) coming from public sources and $55 billion (equivalent to $78.8 billion in 2021[100]) coming from private sources.[101][102] These investments into medical research have made the US the leader in medical innovation, measured either in terms of revenue or the number of new drugs and devices introduced.[12][13] In 2016, the research and development spending by pharmaceutical companies in the US was estimated to be around $59 billion (equivalent to $66 billion in 2021[100]).[103] In 2006, the US accounted for three quarters of the world's biotechnology revenues and 82% of world R&D spending in biotechnology.[12][13] According to multiple international pharmaceutical trade groups, the high cost of patented drugs in the US has encouraged substantial reinvestment in such research and development.[12][13][104] Though, the ACA will force industry to sell medicine at a cheaper price.[105] Due to this, it is possible budget cuts will be made on research and development of human health and medicine in the US.[105] In 2022, the United States had 10,265 drugs in the works, more than twice as many as China and the European Union, and four times as many as the United Kingdom.[106]

Healthcare provider employment in the US

A major impending demographic shift in the US will require the healthcare system to provide more care, as the older population is predicted to increase medical expenses by 5% or more in North America[107] due to the "baby boomers" reaching retirement age.[108] The overall spending on healthcare has increased since the late 1990s, and not just due to general price raises as the rate of spending is growing faster than the rate of inflation.[109] Moreover, the expenditure on health services for people over 45 years old is 8.3 times the maximum of that of those under 45 years old.[110]

Alternative medicine

Other methods of medical treatment are being practiced more frequently than before. This field is labeled Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) and are defined as therapies generally not taught in medical school nor available in hospitals. They include herbs, massages, energy healing, homeopathy, faith healing, and, more recently popularized, cryotherapy, cupping, and Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation or TMS.[111] Providers of these CAM treatments are sometimes legally considered healthcare providers in the US.[112] Common reasons for seeking these alternative approaches included improving their well-being, engaging in a transformational experience, gaining more control over their own health, or finding a better way to relieve symptoms caused by chronic disease. They aim to treat not just physical illness but fix its underlying nutritional, social, emotional, and spiritual causes. In a 2008 survey, it was found that 37% of hospitals in the US offer at least one form of CAM treatment, the main reason being patient demand (84% of hospitals).[113] Costs for CAM treatments average $33.9 (equivalent to $47.84 in 2022[28]) with two-thirds being out-of-pocket, according to a 2007 statistical analysis.[114] Moreover, CAM treatments covered 11.2% of total out-of-pocket payments on healthcare.[114] During 2002 to 2008, spending on CAM was on the rise, but usage has since plateaued to about 40% of adults in the US[115]

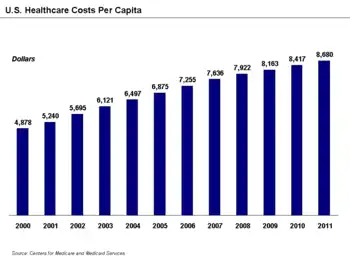

Spending

The US spends more as a percentage of GDP than similar countries, and this can be explained either through higher prices for services themselves, higher costs to administer the system, or more utilization of these services, or to a combination of these elements.[117] Healthcare costs rising far faster than inflation have been a major driver for healthcare reform in the US. As of 2016, the US spent $3.3 trillion (equivalent to $3.69 trillion in 2021;[100] 17.9% of GDP), or $10,438 (equivalent to $12,728 in 2022[28]) per person; major categories included 32% on hospital care, 20% on physician and clinical services, and 10% on prescription drugs.[118] In comparison, the United Kingdom spent $3,749 (equivalent to $4,571 in 2022[28]) per person.[119]

In 2018, an analysis concluded that prices and administrative costs were largely the cause of the high costs, including prices for labor, pharmaceuticals, and diagnostics.[120][121] The combination of high prices and high volume can cause particular expense; in the US, high-margin high-volume procedures include angioplasties, C-sections, knee replacements, and CT and MRI scans; CT and MRI scans also showed higher utilization in the US.[122]

Aggregate US hospital costs were $387.3 billion in 2011—a 63% increase since 1997 (inflation adjusted). Costs per stay increased 47% since 1997, averaging $10,000 in 2011 (equivalent to $13,009 in 2022[28]).[123] As of 2008, public spending accounts for between 45% and 56% of US healthcare spending.[124] Surgical, injury, and maternal and neonatal health hospital visit costs increased by more than 2% each year from 2003–2011. Further, while average hospital discharges remained stable, hospital costs rose from $9,100 in 2003 (equivalent to $14,476 in 2022[28]) to $10,600 in 2011 (equivalent to $13,789 in 2022[28]) and were projected to be $11,000 by 2013 (equivalent to $13,819 in 2022[28]).[125]

According to the WHO, total healthcare spending in the US was 18% of its GDP in 2011, the highest in the world.[126] The Health and Human Services Department expects that the health share of GDP will continue its historical upward trend, reaching 19% of GDP by 2017.[127][128] Of each dollar spent on healthcare in the US, 31% goes to hospital care, 21% goes to physician/clinical services, 10% to pharmaceuticals, 4% to dental, 6% to nursing homes and 3% to home healthcare, 3% for other retail products, 3% for government public health activities, 7% to administrative costs, 7% to investment, and 6% to other professional services (physical therapists, optometrists, etc.).[129]

In 2017, a study estimated that nearly half of hospital-associated care resulted from emergency department visits.[130] As of 2017, data from 2009–2011 showed that end-of-life care in the last year of life accounted for about 8.5%, and the last three years of life about 16.7%.[131]

As of 2013, administration of healthcare constituted 30% of US healthcare costs.[132]

Free-market advocates claim that the healthcare system is "dysfunctional" because the system of third-party payments from insurers removes the patient as a major participant in the financial and medical choices that affect costs. The Cato Institute claims that because government intervention has expanded insurance availability through programs such as Medicare and Medicaid, this has exacerbated the problem.[133] According to a study paid for by America's Health Insurance Plans (a Washington lobbyist for the health insurance industry) and carried out by PriceWaterhouseCoopers, increased utilization is the primary driver of rising healthcare costs in the US[134] The study cites numerous causes of increased utilization, including rising consumer demand, new treatments, more intensive diagnostic testing, lifestyle factors, the movement to broader-access plans, and higher-priced technologies.[134] The study also mentions cost-shifting from government programs to private payers. Low reimbursement rates for Medicare and Medicaid have increased cost-shifting pressures on hospitals and doctors, who charge higher rates for the same services to private payers, which eventually affects health insurance rates.[135]

In March 2010, Massachusetts released a report on the cost drivers which it called "unique in the nation".[136] The report noted that providers and insurers negotiate privately, and therefore the prices can vary between providers and insurers for the same services, and it found that the variation in prices did not vary based on quality of care but rather on market leverage; the report also found that price increases rather than increased utilization explained the spending increases in the past several years.[136]

Economists Eric Helland and Alex Tabarrok speculate that the increase in costs of healthcare in the US are largely a result of the Baumol effect. Since healthcare is relatively labor intensive, and productivity in the service sector has lagged that in the goods-producing sector, the costs of those services will rise relative to goods.[137]

Regulation and oversight

Involved organizations and institutions

Healthcare is subject to extensive regulation at both the federal and the state level, much of which "arose haphazardly".[138] Under this system, the federal government cedes primary responsibility to the states under the McCarran–Ferguson Act. Essential regulation includes the licensure of healthcare providers at the state level and the testing and approval of pharmaceuticals and medical devices by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and laboratory testing. These regulations are designed to protect consumers from ineffective or fraudulent healthcare. Additionally, states regulate the health insurance market and they often have laws which require that health insurance companies cover certain procedures,[139] although state mandates generally do not apply to the self-funded healthcare plans offered by large employers, which exempt from state laws under preemption clause of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act.

In 2010, the ACA was signed by President Barack Obama and includes various new regulations, with one of the most notable being a health insurance mandate which requires all citizens to purchase health insurance. While not regulation per se, the federal government also has a major influence on the healthcare market through its payments to providers under Medicare and Medicaid, which in some cases are used as a reference point in the negotiations between medical providers and insurance companies.[138]

At the federal level, US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) oversees the various federal agencies involved in healthcare. The health agencies are a part of the US Public Health Service, and include the FDA, which certifies the safety of food, effectiveness of drugs and medical products, the CDC, which prevents disease, premature death, and disability, the Agency of Health Care Research and Quality, the Agency Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, which regulates hazardous spills of toxic substances, and the National Institutes of Health, which conducts medical research.

State governments maintain state health departments, and local governments (counties and municipalities) often have their own health departments, usually branches of the state health department. Regulations of a state board may have executive and police strength to enforce state health laws. In some states, all members of state boards must be healthcare professionals. Members of state boards may be assigned by the governor or elected by the state committee. Members of local boards may be elected by the mayor council. The McCarran–Ferguson Act, which cedes regulation to the states, does not itself regulate insurance, nor does it mandate that states regulate insurance. "Acts of Congress" that do not expressly purport to regulate the "business of insurance" will not preempt state laws or regulations that regulate the "business of insurance". The act also provides that federal anti-trust laws will not apply to the "business of insurance" as long as the state regulates in that area, but federal anti-trust laws will apply in cases of boycott, coercion, and intimidation. By contrast, most other federal laws will not apply to insurance whether the states regulate in that area or not.

Self-policing of providers by providers is a major part of oversight. Many healthcare organizations also voluntarily submit to inspection and certification by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospital Organizations (JCAHO). Providers also undergo testing to obtain board certification attesting to their skills. A report issued by Public Citizen in April 2008 found that, for the third year in a row, the number of serious disciplinary actions against physicians by state medical boards declined from 2006 to 2007, and called for more oversight of the boards.[140]

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes an online searchable database of performance data on nursing homes.[141]

In 2004, libertarian think tank Cato Institute published a study which concluded that regulation provides benefits in the amount of $170 billion but costs the public up to $340 billion.[142] The study concluded that the majority of the cost differential arises from medical malpractice, FDA regulations, and facilities regulations.[142]

"Certificates of need" for hospitals

In 1978, the federal government required that all states implement Certificate of Need (CON) programs for cardiac care, meaning that hospitals had to apply and receive certificates prior to implementing the program; the intent was to reduce cost by reducing duplicate investments in facilities.[143] It has been observed that these certificates could be used to increase costs through weakened competition.[138] Many states removed the CON programs after the federal requirement expired in 1986, but some states still have these programs.[143] Empirical research looking at the costs in areas where these programs have been discontinued have not found a clear effect on costs, and the CON programs could decrease costs because of reduced facility construction or increase costs due to reduced competition.[143]

Licensing of providers

The American Medical Association (AMA) has lobbied the government to highly limit physician education since 1910, currently at 100,000 doctors per year,[144] which has led to a shortage of doctors.[145]

An even bigger problem may be that the doctors are paid for procedures instead of results.[146]

The AMA has also aggressively lobbied for many restrictions that require doctors to carry out operations that might be carried out by cheaper workforce. For example, in 1995, 36 states banned or restricted midwifery even though it delivers equally safe care to that by doctors.[144] The regulation lobbied by the AMA has decreased the amount and quality of healthcare, according to the consensus of economist: the restrictions do not add to quality, they decrease the supply of care.[144] Moreover, psychologists, nurses and pharmacists are not allowed to prescribe medicines. Previously nurses were not even allowed to vaccinate the patients without direct supervision by doctors.

36 states require that healthcare workers undergo criminal background checks.[147]

Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA)

EMTALA, enacted by the federal government in 1986, requires that hospital emergency departments treat emergency conditions of all patients regardless of their ability to pay and is considered a critical element in the "safety net" for the uninsured, but established no direct payment mechanism for such care. Indirect payments and reimbursements through federal and state government programs have never fully compensated public and private hospitals for the full cost of care mandated by EMTALA. More than half of all emergency care in the US now goes uncompensated.[148] According to some analyses, EMTALA is an unfunded mandate that has contributed to financial pressures on hospitals in the last 20 years, causing them to consolidate and close facilities, and contributing to emergency room overcrowding. According to the Institute of Medicine, between 1993 and 2003, emergency room visits in the US grew by 26%, while in the same period, the number of emergency departments declined by 425.[149]

Mentally ill patients present a unique challenge for emergency departments and hospitals. In accordance with EMTALA, mentally ill patients who enter emergency rooms are evaluated for emergency medical conditions. Once mentally ill patients are medically stable, regional mental health agencies are contacted to evaluate them. Patients are evaluated as to whether they are a danger to themselves or others. Those meeting this criterion are admitted to a mental health facility to be further evaluated by a psychiatrist. Typically, mentally ill patients can be held for up to 72 hours, after which a court order is required.

Quality assurance

Healthcare quality assurance consists of the "activities and programs intended to assure or improve the quality of care in either a defined medical setting or a program. The concept includes the assessment or evaluation of the quality of care; identification of problems or shortcomings in the delivery of care; designing activities to overcome these deficiencies; and follow-up monitoring to ensure effectiveness of corrective steps."[150] Private companies such as Grand Rounds also release quality information and offer services to employers and plans to map quality within their networks.[151]

One innovation in encouraging quality of healthcare is the public reporting of the performance of hospitals, health professionals or providers, and healthcare organizations. However, there is "no consistent evidence that the public release of performance data changes consumer behaviour or improves care".[152]

Overall system effectiveness

Measures of effectiveness

The US healthcare delivery system unevenly provides medical care of varying quality to its population.[153] In a highly effective healthcare system, individuals would receive reliable care that meets their needs and is based on the best scientific knowledge available. In order to monitor and evaluate system effectiveness, researchers and policy makers track system measures and trends over time. The HHS populates a publicly available dashboard called the Health System Measurement Project (healthmeasures.aspe.hhs.gov), to ensure a robust monitoring system. The dashboard captures the access, quality and cost of care; overall population health; and health system dynamics (e.g., workforce, innovation, health information technology). Included measures align with other system performance measuring activities including the HHS Strategic Plan,[154] the Government Performance and Results Act, Healthy People 2020, and the National Strategies for Quality and Prevention.[155][156]

Waiting times

Waiting times in US healthcare are usually short, but are not usually 0 for non-urgent care at least. Also, a minority of US patients wait longer than is perceived. In a 2010 Commonwealth Fund survey, most Americans self-reported waiting less than four weeks for their most recent specialist appointment and less than one month for elective surgery. However, about 30% of patients reported waiting longer than one month for elective surgery, and about 20% longer than four weeks for their most recent specialist appointment.[157] These percentages were smaller than in France, the UK, New Zealand, and Canada, but not better than Germany and Switzerland (although waits shorter than four weeks/one month may not be equally long across these three countries). The number of respondents may not be enough to be fully representative. In a study in 1994 comparing Ontario to three regions of the US, self-reported mean wait times to see an orthopedic surgeon were two weeks in those parts of the US, and four weeks in Canada. Mean waits for the knee or hip surgery were self-reported as three weeks in those parts of the US and eight weeks in Ontario.[158]

However, current waits in both countries' regions may have changed since then (certainly in Canada waiting times went up later).[159] More recently, at one Michigan hospital, the waiting time for the elective surgical operation open carpel tunnel release was an average of 27 days, most ranging from 17 to 37 days (an average of almost four weeks, ranging from about 2.4 weeks to 5.3 weeks). This appears to be short compared with Canada's waiting time but may compare less favorably to countries like Germany, the Netherlands (where the goal was five weeks), and Switzerland.

It is unclear how many of the patients waiting longer have to. Some may be by choice, because they wish to go to a well-known specialist or clinic that many people wish to attend, and are willing to wait to do so. Waiting times may also vary by region. One experiment reported that uninsured patients experienced longer waits; patients with poor insurance coverage probably face a disproportionate number of long waits.

US healthcare tends to rely on rationing by exclusion (uninsured and underinsured), out-of-pocket costs for the insured, fixed payments per case to hospitals (resulting in very short stays), and contracts that manage demand instead.

Population health: quality, prevention, vulnerable populations

The health of the population is also viewed as a measure of the overall effectiveness of the healthcare system. The extent to which the population lives longer healthier lives signals an effective system.

- While life expectancy is one measure, the HHS uses a composite health measure that estimates not only the average length of life but also the part of life expectancy that is expected to be "in good or better health, as well as free of activity limitations". Between 1997 and 2010, the number of expected high quality life years increased from 61.1 to 63.2 years for newborns.[161]

- The underutilization of preventative measures, rates of preventable illness and prevalence of chronic disease suggest that the US healthcare system does not sufficiently promote wellness.[155] Over the past decade rates of teen pregnancy and low birth rates have come down significantly, but not disappeared.[162] Rates of obesity, heart disease (high blood pressure, controlled high cholesterol), and type 2 diabetes are areas of major concern. While chronic disease and multiple comorbidities became increasingly common among a population of elderly Americans who were living longer, the public health system has also found itself fending off a rise of chronically ill younger generation. According to the US Surgeon General "The prevalence of obesity in the US more than doubled (from 15% to 34%) among adults and more than tripled (from 5% to 17%) among children and adolescents from 1980 to 2008."[163]

- A concern for the health system is that the health gains do not accrue equally to the entire population. In the US, disparities in healthcare and health outcomes are widespread.[164] Minorities are more likely to develop serious illnesses (e.g., type 2 diabetes, heart disease and colon cancer) and less likely to have access to quality healthcare, including preventative services.[165] Efforts are underway to close the gap and to provide a more equitable system of care.

Innovation: workforce, healthcare IT, R&D

Finally, the US tracks investment in the healthcare system in terms of a skilled healthcare workforce, meaningful use of healthcare IT, and R&D output. This aspect of the healthcare system performance dashboard is important to consider when evaluating cost of care in the US. That is because in much of the policy debate around the high cost of US healthcare, proponents of highly specialized and cutting-edge technologies point to innovation as a marker of an effective healthcare system.[166]

Compared to other countries

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

A 2014 study by the private US foundation Commonwealth Fund found that although the US healthcare system is the most expensive in the world, it ranks last on most dimensions of performance when compared with Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK. The study found that the US failed to achieve better outcomes than other countries, and is last or near last in terms of access, efficiency, and equity. Study data came from international surveys of patients and primary care physicians, as well as information on healthcare outcomes from Commonwealth Fund, the WHO, and the OECD.[168][169]

As of 2017, the US stands 43rd in the world with a life expectancy of 80.00 years.[170] In 2007, the CIA World Factbook ranked the US 180th worst (out of 221)—meaning 42nd best—in the world for infant mortality rate (5.01/1,000 live births).[171] Americans also undergo cancer screenings at significantly higher rates than people in other developed countries, and access MRI and CT scans at the highest rate of any OECD nation.[172]

A study found that between 1997 and 2003, preventable deaths declined more slowly in the US than in 18 other industrialized nations.[173] A 2008 study found that 101,000 people a year die in the US that would not if the healthcare system were as effective as that of France, Japan, or Australia.[174] A 2020 study by the economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton argues that the US "spends huge sums of money for some of the worst health outcomes in the Western world".[175]

The OECD found that the US ranked poorly in terms of years of potential life lost (YPLL), a statistical measure of years of life lost under the age of 70 that were amenable to being saved by healthcare. Among OECD nations for which data are available, the US ranked third last for the healthcare of women (after Mexico and Hungary) and fifth last for men (Slovakia and Poland also ranked worse).

Recent studies find growing gaps in life expectancy based on income and geography. In 2008, a government-sponsored study found that life expectancy declined from 1983 to 1999 for women in 180 counties, and for men in 11 counties, with most of the life expectancy declines occurring in the Deep South, Appalachia, along the Mississippi River, in the Southern Plains, and in Texas. The difference is as high as three years for men, six years for women. The gap is growing between rich and poor and by educational level, but narrowing between men and women and by race.[176] Another study found that the mortality gap between the well-educated and the poorly educated widened significantly between 1993 and 2001 for adults ages 25 through 64; the authors speculated that risk factors such as smoking, obesity and high blood pressure may lie behind these disparities.[177] In 2011 the US National Research Council forecasted that deaths attributed to smoking, on the decline in the US, will drop dramatically, improving life expectancy; it also suggested that one-fifth to one-third of the life expectancy difference can be attributed to obesity which is the worst in the world and has been increasing.[178] In an analysis of breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and prostate cancer diagnosed during 1990–1994 in 31 countries, the US had the highest five-year relative survival rate for breast cancer and prostate cancer, although survival was systematically and substantially lower in Black US men and women.[179]

The debate about US healthcare concerns questions of access, efficiency, and quality purchased by the high sums spent. The WHO in 2000 ranked the US healthcare system first in responsiveness, but 37th in overall performance and 72nd by overall level of health (among 191 member nations included in the study).[180][181] The WHO study has been criticized by the free market advocate David Gratzer because "fairness in financial contribution" was used as an assessment factor, marking down countries with high per-capita private or fee-paying health treatment.[182] The WHO study has been criticized, in an article published in Health Affairs, for its failure to include the satisfaction ratings of the general public.[183] The study found that there was little correlation between the WHO rankings for health systems and the stated satisfaction of citizens using those systems.[183] Countries such as Italy and Spain, which were given the highest ratings by WHO were ranked poorly by their citizens while other countries, such as Denmark and Finland, were given low scores by WHO but had the highest percentages of citizens reporting satisfaction with their healthcare systems.[183] WHO staff, however, say that the WHO analysis does reflect system "responsiveness" and argue that this is a superior measure to consumer satisfaction, which is influenced by expectations.[184] Furthermore, the relationship between patient satisfaction and healthcare utilization, expenditures, clinically meaningful measures, and the evaluation of outcomes is complex, not well defined, and only beginning to be explored.[185][186]

A report released in April 2008 by the Foundation for Child Development, which studied the period from 1994 through 2006, found mixed results for the health of children in the US Mortality rates for children ages 1 through 4 dropped by a third, and the percentage of children with elevated blood lead levels dropped by 84%. The percentage of mothers who smoked during pregnancy also declined. On the other hand, both obesity and the percentage of low-birth weight babies increased. The authors note that the increase in babies born with low birth weights can be attributed to women delaying childbearing and the increased use of fertility drugs.[187][188]

In a sample of 13 developed countries, the US was third in its population weighted usage of medication in 14 classes in both 2009 and 2013. The drugs studied were selected on the basis that the conditions treated had high incidence, prevalence and/or mortality, caused significant long-term morbidity and incurred high levels of expenditure and significant developments in prevention or treatment had been made in the last 10 years. The study noted considerable difficulties in cross border comparison of medication use.[189]

A critic of the US healthcare system, British philanthropist Stan Brock, whose charity Remote Area Medical has served over half a million uninsured Americans, stated, "You could be blindfolded and stick a pin on a map of America and you will find people in need."[190] The charity has over 700 clinics and 80,000 volunteer doctors and nurses around the US Simon Usborne of The Independent writes that in the UK "General practitioners are amazed to hear that poor Americans should need to rely on a charity that was originally conceived to treat people in the developing world."[190]

System efficiency and equity

Variations in the efficiency of healthcare delivery can cause variations in outcomes. The Dartmouth Atlas Project, for instance, reported that, for over 20 years, marked variations in how medical resources are distributed and used in the US were accompanied by marked variations in outcomes.[193] The willingness of physicians to work in an area varies with the income of the area and the amenities it offers, a situation aggravated by a general shortage of doctors in the US, particularly those who offer primary care. The ACA is anticipated to produce an additional demand for services which the existing stable of primary care doctors will be unable to fill, particularly in economically depressed areas. Training additional physicians would require some years.[194]

Lean manufacturing techniques such as value stream mapping can help identify and subsequently mitigate waste associated with costs of healthcare. Other product engineering tools such as FMEA and Fish Bone Diagrams have been used to improve efficiencies in healthcare delivery.[195]

Since 2004 the Commonwealth Fund has produced reports comparing healthcare systems in high income countries using survey and administrative data from the OECD and WHO which is analyzed under five themes: access to care, the care process, administrative efficiency, equity and healthcare outcomes. The US has been assessed as worst healthcare system overall among 11 high-income countries in every report, even though it spends the highest proportion of its gross domestic product on healthcare. In 2021 Norway, the Netherlands and Australia were the top-performing countries. The US spent 16.8% of GDP on healthcare in 2019; the next highest country on the list was Switzerland, at 11.3% of GDP. The lowest was New Zealand, which spent roughly 9% of its GDP on healthcare in 2019. It "consistently demonstrated the largest disparities between income groups" across indicators, apart from those related to preventive services and the safety of care.[196]

Preventable deaths

In 2010, coronary artery disease, lung cancer, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and traffic accidents caused the most years of life lost in the US. Low back pain, depression, musculoskeletal disorders, neck pain, and anxiety caused the most years lost to disability. The most deleterious risk factors were poor diet, tobacco smoking, obesity, high blood pressure, high blood sugar, physical inactivity, and alcohol use. Alzheimer's disease, drug abuse, kidney disease and cancer, and falls caused the most additional years of life lost over their age-adjusted 1990 per-capita rates.[60]

Between 1990 and 2010, among the 34 countries in the OECD, the US dropped from 18th to 27th in age-standardized death rate. The US dropped from 23rd to 28th for age-standardized years of life lost. It dropped from 20th to 27th in life expectancy at birth. It dropped from 14th to 26th for healthy life expectancy.[60]

According to a 2009 study conducted at Harvard Medical School by cofounders of Physicians for a National Health Program, a pro-single payer lobbying group, and published by the American Journal of Public Health, lack of health coverage is associated with nearly 45,000 excess preventable deaths annually.[197][198] Since then, as the number of uninsured has risen from about 46 million in 2009 to 49 million in 2012, the number of preventable deaths due to lack of insurance has grown to about 48,000 per year.[199] The group's methodology has been criticized by economist John C. Goodman for not looking at cause of death or tracking insurance status changes over time, including the time of death.[200]

A 2009 study by former Clinton policy adviser Richard Kronick published in the journal Health Services Research found no increased mortality from being uninsured after certain risk factors were controlled for.[201]

Value for money

A study of international healthcare spending levels published in the health policy journal Health Affairs in the year 2000 found that the US spends substantially more on healthcare than any other country in the OECD (OECD), and that the use of healthcare services in the US is below the OECD median by most measures. The authors of the study conclude that the prices paid for healthcare services are much higher in the US than elsewhere.[202] While the 19 next most wealthy countries by GDP all pay less than half what the US does for healthcare, they have all gained about six years of life expectancy more than the US since 1970.[58]

Delays in seeking care and increased use of emergency care

Uninsured Americans are less likely to have regular healthcare and use preventive services. They are more likely to delay seeking care, resulting in more medical crises, which are more expensive than ongoing treatment for such conditions as diabetes and high blood pressure. A 2007 study published in JAMA concluded that uninsured people were less likely than the insured to receive any medical care after an accidental injury or the onset of a new chronic condition. The uninsured with an injury were also twice as likely as those with insurance to have received none of the recommended follow-up care, and a similar pattern held for those with a new chronic condition.[203] Uninsured patients are twice as likely to visit hospital emergency rooms as those with insurance; burdening a system meant for true emergencies with less-urgent care needs.[204]

In 2008 researchers with the American Cancer Society found that individuals who lacked private insurance (including those covered by Medicaid) were more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancer than those who had such insurance.[205]

Variations in provider practices

The treatment given to a patient can vary significantly depending on which healthcare providers they use. Research suggests that some cost-effective treatments are not used as often as they should be, while overutilization occurs with other healthcare services. Unnecessary treatments increase costs and can cause patients unnecessary anxiety.[206] The use of prescription drugs varies significantly by geographic region.[207] The overuse of medical benefits is known as moral hazard—individuals who are insured are then more inclined to consume healthcare. The way the healthcare system tries to eliminate this problem is through cost sharing tactics like copays and deductibles. If patients face more of the economic burden they will then only consume healthcare when they perceive it to be necessary. According to the RAND health insurance experiment, individuals with higher coinsurance rates consumed less healthcare than those with lower rates. The experiment concluded that with less consumption of care there was generally no loss in societal welfare but, for the poorer and sicker groups of people there were definitely negative effects. These patients were forced to forgo necessary preventative care measures in order to save money leading to late diagnosis of easily treated diseases and more expensive procedures later. With less preventative care, the patient is hurt financially with an increase in expensive visits to the ER. The healthcare costs in the US will also rise with these procedures as well. More expensive procedures lead to greater costs.[208][209]

One study has found significant geographic variations in Medicare spending for patients in the last two years of life. These spending levels are associated with the amount of hospital capacity available in each area. Higher spending did not result in patients living longer.[210][211]

Care coordination

Primary care doctors are often the point of entry for most patients needing care, but in the fragmented healthcare system of the US, many patients and their providers experience problems with care coordination. For example, a Harris Interactive survey of California physicians found that:

- Four of every ten physicians report that their patients have had problems with coordination of their care in the last 12 months.

- More than 60% of doctors report that their patients "sometimes" or "often" experience long wait times for diagnostic tests.

- Some 20% of doctors report having their patients repeat tests because of an inability to locate the results during a scheduled visit.[212]

According to an article in The New York Times, the relationship between doctors and patients is deteriorating.[213] A study from Johns Hopkins University found that roughly one in four patients believe their doctors have exposed them to unnecessary risks, and anecdotal evidence such as self-help books and web postings suggest increasing patient frustration. Possible factors behind the deteriorating doctor/patient relationship include the current system for training physicians and differences in how doctors and patients view the practice of medicine. Doctors may focus on diagnosis and treatment, while patients may be more interested in wellness and being listened to by their doctors.[213]

Many primary care physicians no longer see their patients while they are in the hospital; instead, hospitalists are used.[214] The use of hospitalists is sometimes mandated by health insurance companies as a cost-saving measure which is resented by some primary care physicians.[215]

Administrative costs

As of 2017, there were 907 health insurance companies in the US,[216] although the top 10 account for about 53% of revenue and the top 100 account for 95% of revenue.[217]: 70 The number of insurers contributes to administrative overhead in excess of that in nationalized, single-payer systems, such as that in Canada, where administrative overhead was estimated to be about half of the US.[218]

Insurance industry group America's Health Insurance Plans estimates that administrative costs have averaged approximately 12% of premiums over the last 40 years, with costs shifting away from adjudicating claims and towards medical management, nurse help lines, and negotiating discounted fees with healthcare providers.[219]

A 2003 study published by the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association (BCBSA) also found that health insurer administrative costs were approximately 11% to 12% of premiums, with Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans reporting slightly lower administrative costs, on average, than commercial insurers.[220] For the period 1998 through 2003, average insurer administrative costs declined from 13% to 12% of premiums. The largest increases in administrative costs were in customer service and information technology, and the largest decreases were in provider services and contracting and in general administration.[221] The McKinsey Global Institute estimated that excess spending on "health administration and insurance" accounted for as much as 21% of the estimated total excess spending ($477 billion in 2003).[222]

According to a report published by the CBO in 2008, administrative costs for private insurance represent approximately 12% of premiums. Variations in administrative costs between private plans are largely attributable to economies of scale. Coverage for large employers has the lowest administrative costs. The percentage of premium attributable to administration increases for smaller firms, and is highest for individually purchased coverage.[223] A 2009 study published by BCBSA found that the average administrative expense cost for all commercial health insurance products was represented 9.2% of premiums in 2008.[224] Administrative costs were 11.1% of premiums for small group products and 16.4% in the individual market.[224]

One study of the billing and insurance-related (BIR) costs borne not only by insurers but also by physicians and hospitals found that BIR among insurers, physicians, and hospitals in California represented 20–22% of privately insured spending in California acute care settings.[225]

Long-term living facilities

As of 2014, according to a report published[226] the higher the skill of the RN the lower the cost of a financial burden on the facilities. With a growing elderly population, the number of patients in these long term facilities needing more care creates a jump in financial costs. Based on research done in 2010,[227] annual out of pocket costs jumped 7.5% while the cost for Medicare grew 6.7% annually due to the increases. While Medicare pays for some of the care that the elderly populations receive, 40% of the patients staying in these facilities pay out of pocket.[228]

Third-party payment problem and consumer-driven insurance

Most Americans pay for medical services largely through insurance, and this can distort the incentives of consumers since the consumer pays only a portion of the ultimate cost directly.[138] The lack of price information on medical services can also distort incentives.[138] The insurance which pays on behalf of insureds negotiate with medical providers, sometimes using government-established prices such as Medicaid billing rates as a reference point.[138] This reasoning has led for calls to reform the insurance system to create a consumer-driven healthcare system whereby consumers pay more out-of-pocket.[229] In 2003, the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act was passed, which encourages consumers to have a high-deductible health plan and a health savings account. In October 2019, the state of Colorado proposed running public healthcare option through private insurers, which are to bear the brunt of the costs. Premiums under the public option are touted to be 9% to 18% cheaper by 2022.[230]

Equity

Mental health

In 2020, 52.9 million adults were affected by mental illness, nearly one in five adults in the country. 44.7 million adults were affected in 2016.[232] In 2006, mental disorders were ranked one of the top five most costly medical conditions, with expenditures of $57.5 billion (equivalent to $75.5 billion in 2021[100]).[233] A lack of mental health coverage for Americans bears significant ramifications to the US economy and social system. A report by the US Surgeon General found that mental illnesses are the second leading cause of disability in the nation and affect 20% of all Americans.[234] It is estimated that less than half of all people with mental illnesses receive treatment (or specifically, an ongoing, much needed, and managed care; where medication alone, cannot easily remove mental conditions) due to factors such as stigma and lack of access to care,[235] including a shortage of mental health professionals.[236] Treatment rates are understood to vary between different conditions; as an example, only 16% of adults with schizophrenia and 25% with bipolar disorder were estimated to be untreated with appropriate medication in 2007.[237]

The Paul Wellstone Mental Health and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 mandates that group health plans provide mental health and substance-related disorder benefits that are at least equivalent to benefits offered for medical and surgical procedures. The legislation renews and expands provisions of the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996. The law requires financial equity for annual and lifetime mental health benefits, and compels parity in treatment limits and expands all equity provisions to addiction services. Insurance companies and third-party disability administrators (most notably, Sedgwick CMS) used loopholes and, though providing financial equity, they often worked around the law by applying unequal copayments or setting limits on the number of days spent in inpatient or outpatient treatment facilities.[238][239]

Oral health

In the US, dental care is largely not recognized as healthcare, even though individuals visit a dentist more often than a general practitioner,[240] and thus the field and its practices developed independently. In modern policy and practice, oral health is thus considered distinct from primary health, and dental insurance is separate from health insurance. Disparities in oral healthcare accessibility mean that many populations, including those without insurance, the low-income, uninsured, racial minorities, immigrants, and rural populations, have a higher probability of poor oral health at every age. While changes have been made to address these disparities for children, the oral health disparity in adults of all previously listed populations has remained consistent or worsened.[241]

The magnitude of this health issue is surprising even in New York state, where the Medicaid program includes dental coverage and is one of the most impressive insurance programs in the nation. Seven out of ten older adults (aged ≥ 65) have periodontal disease, and one in four adults (aged > 65) has no teeth.[242] This raises concern about the New York State Department of Health's rule, which prevents Medicaid coverage for the replacement of dentures within eight years of initial placement and a ban on coverage of dental implants.[243] In addition, older adults are more likely than those in younger age groups to have medical conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, that worsen their oral health.

Medical underwriting and the uninsurable

Prior to the ACA, medical underwriting was common, but, after the law came into effect in 2014, it became effectively prohibited.[244]

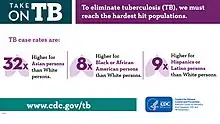

Demographic differences

Health disparities are well documented in the US in ethnic minorities such as African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics.[245] When compared to whites, these minority groups have higher incidence of chronic diseases, higher mortality, poorer health outcomes and poorer rates of diagnosis and treatment.[246][247] Among the disease-specific examples of racial and ethnic disparities in the US is the cancer incidence rate among African Americans, which is 25% higher than among whites.[248] In addition, adult African Americans and Hispanics have approximately twice the risk as whites of developing diabetes and have higher overall obesity rates.[249] Minorities also have higher rates of cardiovascular disease and HIV/AIDS than whites.[248] In the US, Asian Americans live the longest (87.1 years), followed by Latinos (83.3 years), whites (78.9 years), Native Americans (76.9 years), and African Americans (75.4 years).[250] A 2001 study found large racial differences exist in healthy life expectancy at lower levels of education.[251]

Public spending is highly correlated with age; average per capita public spending for seniors was more than five times that for children ($6,921 versus $1,225, equivalent to $11,261 versus $1,993 in 2022[28]). Average public spending for non-Hispanic blacks ($2,973, equivalent to $4,837 in 2022[28]) was slightly higher than that for whites ($2,675, equivalent to $4,352 in 2022[28]), while spending for Hispanics ($1,967, equivalent to $3,200 in 2022[28]) was significantly lower than the population average ($2,612, equivalent to $4,250 in 2022[28])). Total public spending is also strongly correlated with self-reported health status ($13,770 [equivalent to $22,404 in 2022[28]] for those reporting "poor" health versus $1,279 [equivalent to $2,081 in 2022[28]] for those reporting "excellent" health).[124] Seniors comprise 13% of the population but take one-third of all prescription drugs. The average senior fills 38 prescriptions annually.[252] A new study has also found that older men and women in the South are more often prescribed antibiotics than older Americans elsewhere, even though there is no evidence that the South has higher rates of diseases requiring antibiotics.[253]

There is considerable research into inequalities in healthcare. In some cases, these inequalities are caused by income disparities that result in lack of health insurance and other barriers, such as medical equipment, to receiving services.[254] According to the 2009 National Healthcare Disparities Report, uninsured Americans are less likely to receive preventive services in healthcare.[255] For example, minorities are not regularly screened for colon cancer and the death rate for colon cancer has increased among African Americans and Hispanic people. In other cases, inequalities in healthcare reflect a systemic bias in the way medical procedures and treatments are prescribed for different ethnic groups. Raj Bhopal writes that the history of racism in science and medicine shows that people and institutions behave according to the ethos of their times.[256] Nancy Krieger wrote that racism underlies unexplained inequities in healthcare, including treatment for heart disease,[257] renal failure,[258] bladder cancer,[259] and pneumonia.[260] Raj Bhopal writes that these inequalities have been documented in numerous studies. The consistent and repeated findings were that Black Americans received less healthcare than white Americans—particularly when the care involved expensive new technology.[261] One recent study has found that when minority and white patients use the same hospital, they are given the same standard of care.[262][263]

Medical devices are expensive because the process of designing and approving them is long and costly, requiring that they be sold at higher than market price. The costs include: research, design and development, meeting the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's regulatory guidelines, manufacture, marketing, distribution, and business plan.[264] Cost, alongside the impact of systematic oppression and inequality of communities of color within healthcare, together make medical equipment inaccessible. Most studies focused on access to medical devices and enhancement of affordable local production have concluded that increasing access to medical devices in an attempt to meet healthcare needs is extremely important. [265]

The increase of artificial intelligence (AI) in health care raises issues equity and bias related to how health applications are developed and used. A recent scoping review identified 18 equity issues with 15 strategies to address them to try to ensure AI applications equitably meet the needs of the populations intended to benefit from them.[266]

Prescription drug issues

Drug efficiency and safety

The FDA[267] is the primary institution tasked with the safety and effectiveness of human and veterinary drugs. It also is responsible for making sure drug information is accurately and informatively presented to the public. The FDA reviews and approves products and establishes drug labeling, drug standards, and medical device manufacturing standards. It sets performance standards for radiation and ultrasonic equipment.

One of the more contentious issues related to drug safety is immunity from prosecution. In 2004, the FDA reversed a federal policy, arguing that FDA premarket approval overrides most claims for damages under state law for medical devices. In 2008, this was confirmed by the Supreme Court in Riegel v. Medtronic, Inc.[268]

On June 30, 2006, an FDA ruling went into effect extending protection from lawsuits to pharmaceutical manufacturers, even if it was found that they submitted fraudulent clinical trial data to the FDA in their quest for approval. This left consumers who experience serious health consequences from drug use with little recourse. In 2007, the House of Representatives expressed opposition to the FDA ruling, but the Senate took no action. On March 4, 2009, an important US Supreme Court decision was handed down. In Wyeth v. Levine, the court asserted that state-level rights of action could not be pre-empted by federal immunity and could provide "appropriate relief for injured consumers".[269] In June 2009, under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act, Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius signed an order extending protection to vaccine makers and federal officials from prosecution during a declared health emergency related to the administration of the swine flu vaccine.[270][271]

Prescription drug prices

During the 1990s, the price of prescription drugs became a major issue in US politics as the prices of many new drugs increased exponentially, and many citizens discovered that neither the government nor their insurer would cover the cost of such drugs. Per capita, the US spends more on pharmaceuticals than any other country, although expenditures on pharmaceuticals accounts for a smaller share (13%) of total healthcare costs compared to an OECD average of 18% (2003 figures).[272] Some 25% of out-of-pocket spending by individuals is for prescription drugs.[273] Another study finds that between 1990 and 2016, prescription drug prices in the US increased by 277% while prescription drug prices increased by only 57% in the UK, 13% in Canada, and decreased in France and Japan.[274] A November 2020 study by the West Health Policy Center stated that more than 1.1 million senior citizens in the U.S. Medicare program are expected to die prematurely over the next decade because they will be unable to afford their prescription medications, requiring an additional $17.7 billion to be spent annually on avoidable medical costs due to health complications.[275]