Togo

Togo (/ˈtoʊɡoʊ/ ⓘ TOH-goh), officially the Togolese Republic (French: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north.[10] It is one of the least developed countries and extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its capital, Lomé, is located.[10] It is a small, tropical country, which covers 57,000 square kilometres (22,000 square miles)[11] and has a population of approximately 8 million,[12] and has a width of less than 115 km (71 mi) between Ghana and its eastern neighbor Benin.[13][14]

Togolese Republic | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Travail, Liberté, Patrie"[1] (French) "Work, Liberty, Homeland" | |

| Anthem: "Terre de nos aïeux" (French) (English: "Land of our ancestors") | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Lomé 6°8′N 1°13′E |

| Official languages | |

| Spoken languages | |

| Ethnic groups | West African (94.4%)[2] |

| Religion (2020) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Togolese |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party presidential republic |

| Faure Gnassingbé | |

| Victoire Tomegah Dogbé | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from the United Kingdom and France. | |

• Dominion | 6 March 1957 |

• from France | Togoland partitioned |

• Independence granted | 27 April 1960 |

| 27 August 1914 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 57,000[4] km2 (22,000 sq mi) (123rd) |

• Water (%) | 4.2 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 8,703,961[5] (101st) |

• 2022 census | 8,095,498[6] |

• Density | 125.9/km2 (326.1/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2015) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | low · 162nd |

| Currency | West African CFA franc (XOF) |

| Time zone | UTC (GMT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +228 |

| ISO 3166 code | TG |

| Internet TLD | .tg |

| |

Various people groups settled the boundaries of present day Togo between the 11th to 16th centuries. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the coastal region served primarily as a European slave trading outpost, earning Togo and the surrounding region the name "The Slave Coast". In 1884, Germany declared a region including a protectorate called Togoland. After World War I, rule over Togo was transferred to France. Togo gained its independence from France in 1960.[2][15] In 1967, Gnassingbé Eyadéma led a successful military coup d'état, after which he became president of an anti-communist, single-party state. In 1993, Eyadéma faced multiparty elections marred by irregularities, and won the presidency three times. At the time of his death, Eyadéma was the "longest-serving leader in modern African history", having been president for 38 years.[16] In 2005, his son Faure Gnassingbé was elected president.

Togo is a tropical, sub-Saharan nation[10] whose economy depends mostly on agriculture.[15] The official language is French,[15] but other languages are spoken, particularly those of the Gbe family. 47.8% of the population adhere to Christianity, making it the largest religion in the country.[17] Togo is a member of the United Nations, African Union, Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, South Atlantic Peace and Cooperation Zone, Francophonie, Commonwealth, and Economic Community of West African States.

History

Archaeological finds indicate that tribes were able to produce pottery and process iron. The name Togo is translated from the Ewe language as "behind the river". During the period from the 11th century to the 16th century, tribes entered the region: the Ewé from the west, and the Mina and Gun from the east. Most of them settled in coastal areas. The Atlantic slave trade began in the 16th century, and for the next two hundred years the coastal region was a trading centre for Europeans in search of slaves, earning Togo and the surrounding region the name "The Slave Coast".

In 1884, a paper was signed at Togoville with King Mlapa III, whereby Germany claimed a protectorate over a stretch of territory along the coast and gradually extended its control inland. Its borders were defined after the capture of hinterland by German forces and signing agreements with France and Britain. In 1905, this became the German colony of Togoland. The local population was forced to work, cultivate cotton, coffee, and cocoa and pay taxes. A railway and the port of Lomé were built for export of agricultural products. The Germans introduced techniques of cultivation of cocoa, coffee and cotton and developed the infrastructure.

During the First World War, Togoland was invaded by Britain and France, proclaiming the Anglo-French condominium. The Togoland Campaign involved the successful French and British invasion of the German colony of Togoland during the West African Campaign of the First World War. Following the Allied invasion of the colony in August 1914, German forces were defeated, forcing the colony's surrender on 26 August 1914. On 7 December 1916, the condominium collapsed and Togoland was subsequently partitioned into British and French zones, creating the colonies of British Togoland and French Togoland. On 20 July 1922, Great Britain received the League of Nations mandate to govern the western part of Togo and France to govern the eastern part. In 1945, the country received the right to send three representatives to the French parliament.

After World War II, these mandates became UN Trust Territories. The residents of British Togoland voted to join the Gold Coast as part of the independent nation of Ghana in 1957. French Togoland became an autonomous republic within the French Union in 1959, while France retained the right to control the defense, foreign relations, and finances.

The Togolese Republic was proclaimed on 27 April 1960. In the first presidential elections in 1961, Sylvanus Olympio became the first president, gaining 100% of the vote in elections boycotted by the opposition. On 9 April 1961, the Constitution of the Togolese Republic was adopted, according to which the supreme legislative body was the National Assembly of Togo.[18] In December 1961, leaders of opposition parties were arrested because they were accused of the preparation of an anti-government conspiracy. A decree was issued on the dissolution of the opposition parties. Olympio tried to reduce dependence on France by establishing cooperation with the United States, United Kingdom, and West Germany. He rejected the efforts of French soldiers who were demobilized after the Algerian War and tried to get a position in the Togolese army. These factors eventually led to a military coup on 13 January 1963 during which he was assassinated by a group of soldiers under the direction of Sergeant Gnassingbé Eyadéma.[19] A state of emergency was declared in Togo. The military handed over power to an interim government led by Nicolas Grunitzky. In May 1963, Grunitzky was elected President of the Republic. The new leadership pursued a policy of developing relations with France. His main aim was to dampen the divisions between north and south, promulgate a new constitution, and introduce a multiparty system.

On 13 January 1967, Eyadéma Gnassingbé overthrew Grunitzky in a bloodless coup and assumed the presidency.[20] He created the Rally of the Togolese People Party, banned activities of other political parties and introduced a 1-party system in November 1969. He was reelected in 1979 and 1986. In 1983, the privatization program launched and in 1991 other political parties were allowed. In 1993, EU froze the partnership, describing Eyadema's re-election in 1993, 1998 and 2003, as a seizure of power. In April 2004, in Brussels, talks were held between the European Union and Togo on the resumption of cooperation.

Eyadéma Gnassingbé died on 5 February 2005. The military's installation of his son, Faure Gnassingbé,[20] as president provoked international condemnation, except from France. Some "democratically elected" African leaders such as Abdoulaye Wade of Senegal and Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria supported the move, thereby creating a rift within the African Union.[21] Gnassingbé left power and held elections, which he won two months later. The opposition declared that the election results were fraudulent. The events of 2005 led to questions regarding the government's commitment to democracy that had been made in an attempt to normalize relations with EU which cut off aid in 1993 due to questions about Togo's human rights situation. Up to 400 people were killed in the violence surrounding the presidential elections, according to the UN. Around 40,000 Togolese fled to neighboring countries. Gnassingbé was reelected in 2010 and 2015.

In 2017, anti-government protests erupted. UN condemned the resulting crackdown by security forces, and Gambia's foreign minister, Ousainou Darboe, had to issue a correction after saying that Gnassingbé should resign.[22]

In the February 2020 presidential elections, Faure Gnassingbé won his fourth presidential term in office as the president of Togo.[23] According to the official result, he won with a margin of around 72% of the vote share. This enabled him to defeat his closest challenger, the former prime minister Agbeyome Kodjo who had 18%.[24] On 4 May 2020, Bitala Madjoulba, the commander of a Togolese military battalion, was found dead in his office. The day of Madjoulba's death came after the re-elected Faure Gnassingbé had his investiture. An investigation has been opened for this case and all individuals around his death are being questioned.[25]

Togo joined the Commonwealth in June 2022.[26] Prior to its admission at the 2022 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, Foreign Minister Robert Dussey said that he expected Commonwealth membership to provide new export markets, funding for development projects and opportunities for Togolese citizens to learn English and access new educational and cultural resources.[27]

Government

The president is elected by universal and direct suffrage for five years, and is the commander of the armed forces and has the right to initiate legislation and dissolve parliament. Executive power is exercised by the president and the government. The head of government is the Prime Minister who is appointed by the president.

President Gnassingbé Eyadéma, who ruled Togo under a one-party system, died of a heart attack on 5 February 2005. Under the Togolese Constitution, the President of the Parliament, Fambaré Ouattara Natchaba, should have become president of the country, pending a presidential election to be called within 60 days. Natchaba was out of the country, returning on an Air France plane from Paris.[28] The Togolese army, known as Forces Armées Togolaises (FAT), or Togolese Armed Forces, closed the nation's borders, forcing the plane to land in Benin. With an engineered power vacuum, the Parliament voted to remove the constitutional clause that would have required an election within 60 days and declared that Eyadema's son, Faure Gnassingbé, would inherit the presidency and hold office for the rest of his father's term.[28] Faure was sworn in on 7 February 2005, with international criticism of the succession.[29] The African Union described the takeover as a military coup d'état.[30] International pressure also came from the United Nations. Within Togo, opposition to the takeover culminated in riots in which some hundred died. There were uprisings in cities and towns mainly in the southern part of the country. In the town of Aného reports of a general civilian uprising followed by a massacre by government troops. In response, Faure Gnassingbé agreed to hold elections and on 25 February, Gnassingbé resigned as president, and afterward accepted the nomination to run for the office in April.[31]

On 24 April 2005, Gnassingbé was elected president of Togo, receiving over 60% of the vote according to official results. His main rival in the race had been Emmanuel Bob-Akitani from the Union des Forces du Changement (UFC). Electoral fraud was suspected due to a lack of European Union or other independent oversight.[32] Parliament designated Deputy President, Bonfoh Abbass, as interim president until the inauguration.[31] On 3 May 2005, Faure Gnassingbé was sworn in as the new president and the European Union suspended aid to Togo in support of the opposition claims, unlike the African Union and the United States which declared the vote "reasonably fair". The Nigerian president and Chair of AU, Olusẹgun Ọbasanjọ, sought to negotiate between the incumbent government and the opposition to establish a coalition government, and rejected an AU Commission appointment of former Zambian president, Kenneth Kaunda, as special AU envoy to Togo.[33][34] In June, President Gnassingbé named opposition leader Edem Kodjo as the prime minister.

In October 2007, after postponements, elections were held under proportional representation. This allowed the less populated north to seat as many MPs as the more populated south. The president-backed party Rally of the Togolese People (RPT) won a majority with UFC coming second and the other parties claiming inconsequential representation. Vote rigging accusations were leveled at RPT supported by the civil and military security apparatus. With the presence of an EU observer mission, canceled ballots and illegal voting took place, the majority of which in RPT strongholds. On 3 December 2007 Komlan Mally of RPT was appointed to prime minister succeeding Agboyibor. On 5 September 2008, Mally resigned as prime minister of Togo.

Faure Gnassingbé won re-election in the March 2010 presidential election, taking 61% of the vote against Jean-Pierre Fabre from UFC, who had been backed by an opposition coalition called FRAC (Republican Front for Change).[35] Electoral observers noted "procedural errors" and technical problems, and the opposition did not recognize the results, claiming irregularities had affected the outcome.[36][37] Periodic protests against Faure Gnassingbé followed the election.[38] In May 2010, opposition leader Gilchrist Olympio announced that he would enter into a power-sharing deal with the government, a coalition arrangement which provides UFC with eight ministerial posts.[39][40] In June 2012, electoral reforms prompted protesters to take to the street in Lomé for days; protesters sought a return to the 1992 constitution that would re-establish presidential term limits.[41] July 2012 saw the resignation of the prime minister, Gilbert Houngbo.[42] Days later, the commerce minister, Kwesi Ahoomey-Zunu, was named to lead the new government. In the same month, the home of opposition leader Jean-Pierre Fabre was raided by security forces, and thousands of protesters again rallied publicly against the government crackdown.[43]

In April 2015, President Faure Gnassingbé was re-elected for a third term.[44] In February 2020, Faure Gnassingbé was again re-elected for his fourth presidential term. The opposition had accusations of fraud and irregularities.[45] Gnassingbé family has ruled Togo since 1967, meaning it is Africa's longest lasting dynasty.[46]

Administrative divisions

Togo is divided into 5 regions which are subdivided in turn into 30 prefectures. From north to south the regions are Savanes, Kara, Centrale, Plateaux and Maritime.

Foreign relations

While Togo's foreign policy is nonaligned, it has historical and cultural ties with western Europe, especially France and Germany. Togo recognizes the People's Republic of China, North Korea, and Cuba. It re-established relations with Israel in 1987. Togo pursues an active foreign policy and participates in international organizations. It is particularly active in West African regional affairs and in the African Union.

In 2017, Togo signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[47] Togo joined the Commonwealth of Nations, along with Gabon, at the 2022 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Kigali, Rwanda.[26] In joining the Commonwealth, Foreign Minister Robert Dussey told Reuters, the country sought to expand its "diplomatic, political and economic network" and to "forge closer ties with the anglophone world."[27]

Military

FAT (Forces armées togolaises, "Togolese armed forces"), consists of the army, navy, air force, and gendarmerie. Total military expenditures during the fiscal year of 2005 totalled 1.6% of the country's GDP.[2] Military bases exist in Lomé, Temedja, Kara, Niamtougou, and Dapaong.[48] The current Chief of the General Staff is Brigadier General Titikpina Atcha Mohamed, who took office on 19 May 2009.[49] The air force is equipped with Alpha jets.[50]

Human rights

Togo was labeled "Not Free" by Freedom House from 1972 to 1998 and from 2002 to 2006, and has been categorized as "Partly Free" from 1999 to 2001 and from 2007. According to a U.S. State Department report based on conditions in 2010, human rights problems include "security force use of excessive force, including torture, which resulted in deaths and injuries; official impunity; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrests and detention; lengthy pretrial detention; executive influence over the judiciary; infringement of citizens' privacy rights; restrictions on freedoms of press, assembly, and movement; official corruption; discrimination and violence against women; child abuse, including female genital mutilation (FGM), and sexual exploitation of children; regional and ethnic discrimination; trafficking in persons, especially women and children; societal discrimination against persons with disabilities; official and societal discrimination against homosexual persons; societal discrimination against persons with HIV; and forced labor, including by children."[51] Same-sex sexual activity is illegal in Togo,[52] with a penalty of one to three years imprisonment.[53]

Geography

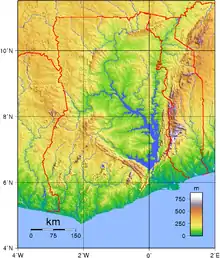

It has an area equal to 56,785 km2 (21,925 sq mi). It borders the Bight of Benin in the south; Ghana lies to the west; Benin to the east; and to the north, it is bound by Burkina Faso. North of the equator, it lies mostly between latitudes 6° and 11°N, and longitudes 0° and 2°E.

The coast of Togo in the Gulf of Guinea is 56 km (35 miles) long and consists of lagoons with sandy beaches. In the north, the land is characterized by a rolling savanna in contrast to the center of the country, which is characterized by hills. The south of Togo is characterized by a savanna and woodland plateau which reaches a coastal plain with lagoons and marshes. The highest mountain of the country is the Mont Agou at 986 metres (3235') above sea level. The longest river is the Mono River with a length of 400 km (250 miles). It runs from north to south.

The climate is "generally tropical"[15] with average temperatures ranging from 23 °C (73 °F) on the coast to about 30 °C (86 °F) in the northernmost regions, with a drier climate and characteristics of a tropical savanna.

Togo contains three terrestrial ecoregions: Eastern Guinean forests, Guinean forest-savanna mosaic, and West Sudanian savanna.[54] The coast of Togo is characterized by marshes and mangroves. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.88/10, ranking it 92nd globally out of 172 countries.[55]

At least five parks and reserves have been established: Abdoulaye Faunal Reserve, Fazao Malfakassa National Park, Fosse aux Lions National Park, Koutammakou,[56] and Kéran National Park.

Wildlife

Economy

The country possesses phosphate deposits[15] and an export sector based on agricultural products such as coffee, cocoa bean, and peanuts (groundnuts), which together generate roughly 30% of export earnings.[15] Cotton is a cash crop.[57] The fertile land occupies 11.3% of the country, most of which is developed. Some crops are cassava, jasmine rice, maize and millet. Some other sectors are brewery and the textile industry. "Low market prices" for Togo's "major export commodities" coupled with the "volatile political situation" of the 1990s and 2000s had a "negative effect" on the economy.[58]

It is listed in the least developed country group. It serves as a regional commercial and trade center. The government's decade-long efforts supported by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to carry out economic reforms, to encourage investments, and to create the balance between income and consumption has stalled. Political unrest, including private and public sector strikes throughout 1992 and 1993, jeopardized the reform program, shrank the tax base, and disrupted economic activities in the country.

It imports machinery, equipment, petroleum products, and food. Its main import partners are France (21.1%), the Netherlands (12.1%), Côte d'Ivoire (5.9%), Germany (4.6%), Italy (4.4%), South Africa (4.3%) and China (4.1%). The main exports are cocoa, coffee, re-export of goods, phosphates and cotton. "Major export partners" are Burkina Faso (16.6%), China (15.4%), the Netherlands (13%), Benin (9.6%) and Mali (7.4%).

In terms of structural reforms, it has made progress in the liberalization of the economy, namely in the fields of trade and port activities. The privatization program of the cotton sector, telecommunications and water supply has stalled.

On 12 January 1994, the devaluation of the currency by 50% provided an impetus to renewed structural adjustment; these efforts were facilitated by the end of strife in 1994 and a return to overt political calm. Progress depends on increased openness in government financial operations (to accommodate increased social service outlays) and possible downsizing of the armed forces, on which the regime has depended to stay in place. Lack of aid and depressed cocoa prices generated a 1% fall in GDP in 1998, with growth resuming in 1999. Togo is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[59]

Agriculture is the "backbone" of the economy.[15] A shortage of funds for the purchase of irrigation equipment and fertilizers has reduced agricultural output. Agriculture generated 28.2% of GDP in 2012 and employed 49% of the working population in 2010. The country is essentially self-sufficient in food production. Livestock production is dominated by cattle breeding.[60][61]

Mining generated about 33.9% of GDP in 2012 and employed 12% of the population in 2010. Togo has the fourth-largest phosphate deposits in the world. Their production is 2.1 million tons per year. There are reserves of limestone, marble and salt. Industry provides 20.4% of Togo's national income, as it consists of light industries and builders. Some reserves of limestone allows Togo to produce cement.[60][62]

Transport

Road

Togo has a road network of 7,520 km (4,670 mi) as of 2000, with no updated data as of 2023. It has only two major highways, Highway N1 and N2, connecting the capital, Lomé with the city of Dapaong, where it gets diverged northwards to Burkina Faso and from there north-west to Mali, and north-east to Niger. N1 is the longest highway of Togo, at a length of 613 km (381 mi). N2 connects Lomé with Aneho. The extension of N2 is Highway RNIE1, or the Trans–West African Coastal Highway, from Aneho to Cotonou in Benin. Other roads and highways are local and regional roads in the rest of the country, also passing through borders with the neighbouring countries. The Trans–West African Coastal Highway crosses Togo, connecting it to Benin and Nigeria to the east, and Ghana and Ivory Coast to the west. Once the construction in Liberia and Sierra Leone part gets completed, the highway will continue west to seven other Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) nations.

Railways

Togo has a railway network of 568 km (353 mi) as of 2008, with no further updates in the network as of 2023. It follows a track gauge of 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) (narrow gauge) Trains are operated by Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer Togolais (SNCT), which was established as a result of the restructuring and renaming of Réseau des Chemins de Fer du Togo from 1997 to 1998.[63] Between Hahotoé and the port of Kpémé, the Compagnie Togolaise des Mines du Bénin (CTMB) operated phosphate trains.[63]

The following are the railway networks present in the country:

- Lomé–Aného railway

- Lomé–Blitta railway

- Lomé–Kpalimé railway

- Hahotoé–Kpémé railway (operated by CTMB)[63]

Air

Togo has a total of eight airports, as of 2012, out of which two are international airports and six are domestic airports. The only major airport of the country is Lomé–Tokoin International Airport serving the capital, Lomé, and another Niamtougou International Airport in Niamtougou, serving the country's northern part.

Water

Togo, in terms of water transport, is only 50 km (31 mi) navigable, mostly seasonally on the Mono River, depending on rainfall, as of 2011. Togo has only one large container port for carrying trade operations in and out of the country, the Port of Lomé, in the capital.

Demographics

| Population[13][14] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 1.4 | ||

| 2000 | 5.0 | ||

| 2021 | 8.6 | ||

The November 2010 census gave Togo a population of 6,191,155, more than double the total counted in the last census, in 2022 the Togo population is 8 680 832.[64] That census, taken in 1981, showed the nation had a population of 2,719,567. The capital, Lomé, grew from 375,499 in 1981 to 837,437 in 2010. When the urban population of surrounding Golfe prefecture is added, the Lomé Agglomeration contained 1,477,660 residents in 2010.[65][66]

Other cities in Togo according to the new census were Sokodé (95,070), Kara (94,878), Kpalimé (75,084), Atakpamé (69,261), Dapaong (58,071) and Tsévié (54,474). With an estimated population of 8,644,829 (as of 2021), Togo is the 107th largest country by population. Most of the population (65%) live in rural villages dedicated to agriculture or pastures. The population of Togo shows a stronger growth: from 1961 (the year after independence) to 2003 it quintupled.[65][66]

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Lomé  Sokodé |

1 | Lomé | Maritime | 1,477,658 |  Kara  Kpalimé | ||||

| 2 | Sokodé | Centrale | 117,811 | ||||||

| 3 | Kara | Kara | 94,878 | ||||||

| 4 | Kpalimé | Plateaux | 75,084 | ||||||

| 5 | Atakpamé | Plateaux | 69,261 | ||||||

| 6 | Dapaong | Savanes | 58,071 | ||||||

| 7 | Tsévié | Maritime | 54,474 | ||||||

| 8 | Anié | Plateaux | 37,398 | ||||||

| 9 | Notsé | Plateaux | 35,039 | ||||||

| 10 | Cinkassé | Savanes | 26,926 | ||||||

Ethnic groups

In Togo, there are about 40 different ethnic groups, the most numerous of which are the Ewe in the south who make up 32% of the population. Along the southern coastline, they account for 21% of the population. Also found are Kotokoli or Tem and Tchamba in the center and the Kabye people in the north (22%). The Ouatchis are 14% of the population. Sometimes the Ewes and Ouatchis are considered the same, while the French who studied both groups considered them different people.[68] Other ethnic groups include the Mina, Mossi, the Moba and Bassar, the Tchokossi of Mango (about 8%).

Religion

Religion in Togo (Arda 2020 estimate)[69]

According to a 2012 US government religious freedoms report, in 2004 the University of Lomé estimated that 33% of the population were traditional animists, 28% were Roman Catholic, 20% Sunni Muslim, 9% Protestant and another 5% belonged to other Christian denominations. The remaining 5% were reported to include persons not affiliated with any religious group. The report noted that "many" Christians and Muslims continue to perform indigenous religious practices.[70]

In 2023, The World Factbook stated that 42.3% of the population are Christian and 14% are Muslim, with 36.9% being followers of indigenous beliefs, less than one percent being Hindus, Jews, and followers of other religions, and 6.2% being unaffiliated.[60]

Christianity began to spread from the middle of the 15th century, after the arrival of Portuguese Catholic missionaries. Germans introduced Protestantism in the second half of the 19th century when a hundred missionaries of the Bremen Missionary Society were sent to the coastal areas of Togo and Ghana. Togo's Protestants were known as "Brema", a corruption of the word "Bremen". After World War I, German missionaries had to leave, which gave birth to the early autonomy of the Ewe Evangelical Church.[71]

In 2022, Freedom House rated Togo's religious freedom as 3 out of 4,[72] noting that religious freedom is constitutionally protected and generally respected in practice. Islam, Catholicism and Protestantism are recognised by the state; other groups must register as religious associations to receive similar benefits. The registration process has been subject to long delays with almost 900 applications pending at the beginning of 2021.

Languages

According to Ethnologue, 39 distinct languages are spoken in the country, some of them by communities that number fewer than 100,000 members.[73] Of the 39 languages, the sole official language is French.[74] Two spoken indigenous languages were designated politically as national languages in 1975: Ewé (Ewe: Èʋegbe; French: Evé) and Kabiyé.[74]

Though not native to most groups, French is used in formal education, legislature, all forms of media, administration and commerce. Ewe is a language of wider communication in the south. Tem functions to a limited extent as a trade language in some northern towns.[75] Officially, Ewe and Kabiye are "national languages", which in the Togolese context means languages that are promoted in formal education and used in the media. Others are Gen, Aja, Moba, Ntcham, and Ife. In joining the Commonwealth, the Togolese government has anticipated opportunities for Togolese citizens to learn English.[27]

Health

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[76] finds that Togo is fulfilling 73.1% of what it should be fulfilling for the right to health based on its level of income.[77] When looking at the right to health with respect to children, Togo achieves 93.8% of what is expected based on its current income.[77] In regards to the right to health amongst the adult population, the country achieves 88.2% of what is expected based on the nation's level of income.[77] It falls into the "very bad" category when evaluating the right to reproductive health because the nation is fulfilling 37.3% of what the nation is expected to achieve based on the resources (income) it has available.[77]

Health expenditure in Togo was 5.2% of GDP in 2014, which ranks the country in 45th place in the world.[60] The infant mortality rate is approximately 43.7 deaths per 1,000 children in 2016.[60] Male life expectancy at birth was at 62.3 in 2016, whereas it was at 67.7 years for females.[60] There were 5 physicians per 100,000 people in 2008[60] According to a 2013 UNICEF report,[78] 4% of women in Togo have undergone female genital mutilation.

As of 2015, the maternal mortality rate per 100,000 births for Togo is 368, compared with 350 in 2010 and 539.7 in 1990.[60] The under 5 mortality rate per 1,000 births is 100, and the neonatal mortality as a percentage of under 5's mortality is 32. In Togo the number of midwives per 1,000 live births is 2 and the lifetime risk of death for pregnant women is 1 in 67.[79]

In 2016, Togo had 4100 (2400-6100) new HIV infections and 5100 (3100-7700) AIDS-related deaths. There were 100,000 (73,000-130,000) people living with HIV in 2016, among whom 51% (37-67%) were accessing antiretroviral therapy. Among pregnant women living with HIV, 86% (59% - >95%) were accessing treatment or prophylaxis to prevent transmission of HIV to their children. An estimated <1000 (<500-1400) children were newly infected with HIV due to mother-to-child transmission. Among people living with HIV, approximately 42% (30-55%) had suppressed viral loads.[80]

AFD is working to enhance living conditions in Lomé, the coastal city with a population of 1.4 million, by modernizing solid waste management services. The project involves enhancing garbage collection through the construction of a new landfill that meets international standards.[81][82]

Education

Education in Togo is compulsory for six years.[83] In 1996, the gross primary enrollment rate was 119.6%, and the net primary enrollment rate was 81.3%.[83] In 2011, the net enrollment rate was 94%. The education system has "suffered from teacher shortages, lower educational quality in rural areas, and high repetition and dropout rates".[83]

Culture

The culture reflects the influences of ethnic groups, the largest of which are the Ewe, Mina, Tem, Tchamba and Kabre. Some people follow native animistic practices and beliefs.

Ewe statuary is characterized by its statuettes which illustrate the worship of the ibeji. Sculptures and hunting trophies were used rather than the "more ubiquitous" African masks. The wood-carvers of Kloto has their "chains of marriage": Two characters are connected by rings whittled from one piece of wood.

The dyed fabric batiks of the artisanal center of Kloto represent stylized and colored scenes of ancient everyday life. There are loincloths used in the ceremonies of the weavers of Assahoun. Works of the painter Sokey Edorh are inspired by the "immense arid extents, swept by the dry wind", and where the soil keeps the prints of the men and the animals. The plastics technician Paul Ahyi practiced the "zota", a kind of pyroengraving, and his monumental achievements decorate Lomé.

Basketball is Togo's "second most practiced sport".[84] Togo featured a national team in beach volleyball that competed at the 2018–2020 CAVB Beach Volleyball Continental Cup in the men's section.[85]

Mass media includes radio, television, and online and print formats. The Agence Togolaise de Presse news agency began in 1975.[86] The Union des Journalistes Independants du Togo press association is headquartered in Lomé.[86]

See also

References

- "Constitution of Togo". 2002. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "Togo". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- "National Profiles".

- "Togo country profile". BBC News. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- "Togo". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Togo-Les résultats définitifs du 5e RGPH". Icilome. 4 April 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Togo)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- "Republic of Togo". Islamic Development Bank. 18 November 1998. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- "Togo country profile". BBC News. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- "Togo country profile". BBC News. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- "World Population Prospects 2022". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX). population.un.org ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- "Togo (Partner) – International Cultural Youth Exchange". International cultural youth exchange. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- "Obituary: Gnassingbe Eyadema". (5 February 2005). BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- "Togo", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 11 January 2023, retrieved 13 January 2023

- "Togo". Ujamaa Live. 26 April 2019. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Ellis, Stephen (1993). "Rumour and Power in Togo". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. Cambridge University Press. 63 (4): 462–476. doi:10.2307/1161002. JSTOR 1161002. S2CID 145261033.

- "Togo Economy: Population, GDP, Inflation, Business, Trade, FDI, Corruption". www.heritage.org. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- BBC News – Togo country profile – Overview. Bbc.co.uk (11 July 2011). Retrieved on March 26 2012.

- Farge, Emma (23 October 2017). "Gambian ministry says up to Togo to resolve crisis". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- "Togo's President Faure Gnassingbé wins fourth term". France 24. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Togo President Faure Gnassingbe wins fourth term in landslide". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Togo: une enquête ouverte après la mort du colonel Bitala Madjoulba" (in French). Radio France Internationale. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Turner, Camilla (22 June 2022). "Togo and Gabon to become newest members of Commonwealth this week". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- Lawson, Alice (24 June 2022). "Togo sees Commonwealth entry as pivot to English-speaking world". Reuters. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- "Togo: Africa's democratic test case". BBC News. 11 February 2005. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Togo leader sworn in amid protest". BBC News. 7 February 2005. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Togo succession 'coup' denounced". BBC News. 6 February 2005. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- Godwin, Ebow (8 June 2010). "Togo Leader to Step Down, Seek Presidency". Associated Press (via SF Gate). Archived from the original on 6 January 2006. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- "Technological shutdowns as tools of oppression". SciDev.net. 20 June 2005. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- "Togo: African Union in Row Over Appointment of Special Envoy". Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). AllAfrica.com. 6 June 2005 - "Togo: African Union in Row Over Appointment of Special Envoy". Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). AllAfrica.com - "Togo's president re-elected: electoral agency". Sydney Morning Herald. 7 March 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Togo opposition vows to challenge election result". BBC. 7 March 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Togo leader Gnassingbe re-elected in disputed poll". Reuters. 6 March 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Togo: 4,000 demonstrators protest Togo election results". AllAfrica.com. 11 April 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Togo opposition 'to join coalition government'". BBC. 27 May 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Togo profile". BBC. 11 July 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Togo protest: Lome rocked by electoral reform unrest". BBC. 14 June 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- "Togo PM, govt quit to widen leadership before vote". Reuters. 12 July 2012. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Huge rally in Togo". news24.com. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Togo's Faure Gnassingbe wins third term as president". BBC News. 29 April 2015.

- "Togo President Gnassingbé wins re-election | DW | 24.02.2020". Deutsche Welle.

- "Togo's dynasty lives on". IPS. 28 February 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

- "Organisation des Forces Armées". www.forcesarmees.tg. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- "Un Nouveau Chef à la Tête des FAT". www.forcesarmees.tg. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- "Togolese Air Force acquires CN235". defenceweb.co.za. 29 August 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- "2010 Human Rights Report: Togo". US Department of State. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Avery, Daniel (4 April 2019). "71 Countries Where Homosexuality is Illegal". Newsweek.

- Itaborahy, Lucas Paoli (May 2013). "State-sponsored Homophobia: A world survey of laws prohibiting same-sex activity between consenting adults" (PDF). The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- "Koutammakou, the Land of the Batammariba". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- "The Fact File". factfile.org. 19 January 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- "Britannica". Britannica.org. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- "OHADA.com: The business law portal in Africa". Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- "Togo". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 27 February 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- Joelle Businger. "Getting Togo's Agriculture Back on Track, and Lifting Rural Families Out of Poverty Along the Way".

- "Togo | Location, History, Population, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- Harris, Ken, ed. (2005). Jane's World Railways 2005-2006 (47th ed.). Jane's Information Group. p. 464. ISBN 0-7106-2710-6.

- "Population Togo - evolution population Togo - Pyramide des âges - age median - demographie - chiffres".

- [RGPH4 Recensement Général de la Population 2010]. Direction Générale de la Statistique et de la Comptabilité Nationale

- Données de Recensement. Direction Générale de la Statistique et de la Comptabilité Nationale

- "Togo". City Population.

- Khan, M. Ali; Sherieff, A.; Balakishan, A. (2007). Encyclopedia of world geography. Sarup & Sons. p. 255. ISBN 978-81-7625-773-2.

- "Religions in Togo | Arda". www.globalreligiousfutures.org. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- "Togo 2012 International Religious Freedom Report" (PDF). 2009-2017 Archive for the U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 2012. p. 1. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- Decalo, Samuel (1996). Historical Dictionary of Togo. Scarecrow Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780810830738.

- Freedom House, Retrieved 2023-04-25

- "Languages of Togo". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- "Country Profile | The Islamic Chamber of Commerce , Industry and Agriculture (ICCIA)". iccia.com. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- "Togo". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- "Human Rights Measurement Initiative – The first global initiative to track the human rights performance of countries". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- "Togo - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- UNICEF 2013 Archived 5 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 27.

- "The State Of The World's Midwifery". United Nations Population Fund. Accessed August 2011.

- "Togo". www.unaids.org.

- Bank, European Investment (23 February 2023). "The Clean Oceans Initiative".

- "Clean Oceans Initiative". www.afd.fr. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- "Togo" Archived 2 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 2001 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Kayi Lawson (28 May 2021). "Le basketball, une discipline en quêtes de moyen et de vocations au Togo". VOA Afrique (in French). Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- "Continental Cup Finals start in Africa". FIVB. 22 June 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- "Togo: Directory". Africa South of the Sahara 2003. Regional Surveys of the World. Europa Publications. 2003. p. 1106+. ISBN 9781857431315. ISSN 0065-3896.

Further reading

- Bullock, A L C, Germany's Colonial Demands (Oxford University Press, 1939).

- Gründer, Horst, Geschichte der deutschen Kolonien, 3. Aufl. (Paderborn, 1995).

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey, Military Coups in West Africa Since The Sixties (Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2001).

- Packer, George, The Village of Waiting (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988).

- Piot, Charles, Nostalgia for the Future: West Africa After the Cold War (University of Chicago Press, 2010).

- Schnee, Dr. Heinrich, German Colonization, Past and Future - the Truth about the German Colonies (George Allen & Unwin, 1926).

- Sebald, Peter, Togo 1884 bis 1914. Eine Geschichte der deutschen "Musterkolonie" auf der Grundlage amtlicher Quellen (Berlin, 1987).

- Seely, Jennifer, The Legacies of Transition Governments in Africa: The Cases of Benin and Togo (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

- Zurstrassen, Bettina, "Ein Stück deutscher Erde schaffen". Koloniale Beamte in Togo 1884-1914 (Frankfurt/M., Campus, 2008) (Campus Forschung, 931).

External links

Government

- Republic of Togo official site (in French)

- National Assembly of Togo official site

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members (in French)

General

- Country Profile from New Internationalist

- Country Profile from BBC News

- Togo from Encyclopædia Britannica

- Togo. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Togo from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Togo at Curlie

Wikimedia Atlas of Togo

Wikimedia Atlas of Togo- Key Development Forecasts for Togo from International Futures

Trade

.svg.png.webp)