Paratha

Paratha (pronounced [pəˈɾɑːtʰɑː]) is a flatbread native to South Asia, with earliest reference mentioned in early medieval Sanskrit text from Karnataka, India;[1] prevalent throughout the modern-day nations of India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Maldives, Afghanistan, Myanmar,[2] Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Mauritius, Fiji, Guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago where wheat is the traditional staple. Paratha is an amalgamation of the words parat and atta, which literally means layers of cooked dough.[3] Alternative spellings and names include parantha, parauntha, prontha, parontay, paronthi (Punjabi), porota (in Bengali), paratha (in Odia, Urdu, Hindi), porotta (in Malayalam, Tamil) , palata (pronounced [pəlàtà]; in Myanmar),[2] porotha (in Assamese), forota (in Sylheti), farata (in Mauritius and the Maldives), prata (in Southeast Asia), paratha, buss-up shut, oil roti (in the Anglophone Caribbean) and Roti Canai in Malaysia.

| |

| Place of origin | Indian subcontinent[1] |

|---|---|

| Associated cuisine | Bangladesh, Fiji, Guyana, India, Malaysia, Maldives, Thailand, Myanmar,[2] Nepal, Pakistan, Gulf countries Singapore, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago |

| Main ingredients | Atta, ghee/butter/cooking oil and various stuffings |

| Variations | Aloo paratha, Roti Canai, Wrap roti |

History

The word paratha is derived from Sanskrit (S. पर, or परा+स्थः, or स्थितः).[4] Recipes for various stuffed wheat puranpolis (which Achaya (2003) describes as parathas) are mentioned in Manasollasa, a 12th-century Sanskrit encyclopedia compiled by Someshvara III, a Western Chalukya king, who ruled from present-day Karnataka, India.[5] References to paratha have also been mentioned by Nijjar (1968), in his book Panjāb under the Sultāns, 1000–1526 AD when he writes that parathas were common with the nobility and aristocracy in the Punjab.[6]

According to Banerji (2010), parathas are associated with Punjabi and North Indian cooking. The Punjabi method is to stuff parathas with a variety of stuffings. However, Banerji states, Mughals were also fond of parathas which gave raise to the Dhakai paratha, multilayered and flaky, taking its name from Dhaka in Bangladesh.[7] O'Brien (2003) suggests that it is not correct to state that the Punjabi paratha was popularised in Delhi after the 1947 partition of India, as the Punjabi item was prevalent in Delhi before then.[8]

Plain and stuffed varieties

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 327 kcal (1,370 kJ) |

45.36 g | |

| Sugars | 4.15 |

| Dietary fiber | 9.6 g |

13.20 g | |

6.36 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 10% 0.11 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 6% 0.076 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 12% 1.830 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 0% 0 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 6% 0.08 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 0% 0 μg |

| Vitamin E | 9% 1.35 mg |

| Vitamin K | 3% 3.4 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 3% 25 mg |

| Iron | 12% 1.61 mg |

| Magnesium | 10% 37 mg |

| Phosphorus | 17% 120 mg |

| Potassium | 3% 139 mg |

| Sodium | 30% 452 mg |

| Zinc | 9% 0.82 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 33.5 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Parathas are one of the most popular unleavened flatbreads in the Indian subcontinent, made with wheat dough from finely ground wholemeal (atta) and/or white flour (maida), sometimes incorporating egg or ghee. Plain parathas are thicker and more substantial than chapatis/rotis because they have been layered by coating with ghee or oil and folded repeatedly, much like the method used for puff pastry or a laminated dough technique, and as a result have a flaky consistency. Stuffed parathas may include a wide variety of ingredients and be made with a variety of preparation styles, traditionally depending on region of origin, and may not use a folded dough techniques.

To achieve the layered dough for plain parathas, a number of different traditional techniques exist.[9] These include covering the thinly rolled out pastry with oil, folding back and forth like a paper fan and coiling the resulting strip into a round shape before rolling flat, baking on a tava and/or shallow frying. Another method is to cut a circle of dough from the center to its circumference along its radius, oiling the dough and starting at the cut edge rolling so as to form a cone which is then squashed into a disc shape and rolled out. The method of oiling and repeatedly folding the dough as in western puff pastry also exists, and this is combined with folding patterns that give traditional geometrical shapes to the finished parathas. Parathas can be round, heptagonal, square, or triangular.

Common stuffed varieties include mashed spiced potatoes (aloo paratha), dal, cauliflower (gobi paratha), and minced lamb (keema paratha). Less common stuffing ingredients include mixed vegetables, green beans, carrots, other meats, leaf vegetables, radishes, and paneer. A Rajasthani mung bean paratha uses both the layering technique together with mung dal mixed into the dough. Some stuffed parathas are not layered, lacking in the flakiness of plain parathas, and instead resemble a filled pie squashed flat and shallow-fried, using two discs of dough sealed around the edges. Alternatively, they can be made by using a single disc of dough to encase a ball of filling and sealed with a series of pleats pinched into the dough around the top, they are gently flattened with the palm against the working surface before being rolled into a circle.

Serving

The paratha is an important part of a traditional breakfast and other meals on the Indian subcontinent. Often a paratha is eaten with butter, chutney, pickles, ketchup, yogurt, or raita as condiments. Dishes often eaten with paratha are meat or vegetable curries, fried egg, omelette, keema matar, nihari, jeera aloo, and dal. Some roll a plain paratha into a tube and eat it with tea (tiffin), optionally dipping the paratha in the tea.

Types

- Aloo paratha (stuffed with spicy boiled potato and onions mix).

- Chili parotha or mirchi paratha (incorporating small, spicy shredded pieces)

- Gobi paratha (stuffed with flavoured cauliflower)

- Mughlai paratha (a deep-fried stuffed paratha filled with egg and minced meat from Bangladesh and West Bengal of India)

- Murthal Paratha, deep-fried, Dhabas of Haryana and specially at Murthal on Grand Trunk Road are famous for this[10][11][12]

- Pashti

- Roti prata (Singapore)

- Roti canai (Malaysia)

- Buss-up-shut (Trinidad; the name is Trinidadian Creole for "busted-up shirt", for the resemblance of the shreddy bread to ragged old clothes)

Punjabi Aloo Paratha served with Butter, from India

Punjabi Aloo Paratha served with Butter, from India

Dhakai Paratha from West Bengal, India

Dhakai Paratha from West Bengal, India Aloo paratha from northern India

Aloo paratha from northern India Paratha served with tea in a Pakistani Hotel

Paratha served with tea in a Pakistani Hotel

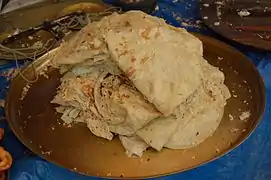

Trinidadian-style roti paratha (buss-up shut)

Trinidadian-style roti paratha (buss-up shut) In Myanmar, paratha is commonly eaten as a dessert, sprinkled with sugar.

In Myanmar, paratha is commonly eaten as a dessert, sprinkled with sugar. Petai Paratha (Smashed Paratha), a West Bengal variant served with light vegetable curry

Petai Paratha (Smashed Paratha), a West Bengal variant served with light vegetable curry Lachha Paratha

Lachha Paratha Kerala style porotta and iracchi curry

Kerala style porotta and iracchi curry

See also

- Gali Paranthe Wali

- Roti canai, a variant from Southeast Asia

- Scallion pancake

- Cōng yóu bǐng, a similar Chinese flatbread stuffed with minced scallions

- Mughlai paratha

- Naan

- List of bread dishes

- List of Indian breads

References

- Chitrita Banerji (10 December 2008). Eating India: An Odyssey into the Food and Culture of the Land of Spices. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-1-59691-712-5.

- Joe Cummings (2000). Myanmar (Burma). Lonely Planet. ISBN 9780864427038.

- Verma, Neera. Mughlai Cook Book. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. ISBN 9788171825479 – via Google Books.

- Platts, John (1884). "A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English". A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English. W. H. Allen & Co. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

parāṭhā [S. पर, or परा+स्थः, or स्थितः], s.m. A cake made with butter or ghī, and of several layers, like pie-crust.

- K. T. Achaya (2003). The Story of Our Food. Universities Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-81-7371-293-7.

- Nijjer, Bakhshish Singh (1968). Panjāb under the sultāns, 1000–1526 A.D. Sterling Publishers

- Banerji, Chitrita (2010). Eating India: Exploring the Food and Culture of the Land of Spices. Bloomsbury.

- O'Brien, Charmaine (2003). Flavours Of Delhi: A Food Lover's Guide. Penguin.

- Jaffrey, Madhur (18 December 2008). Climbing the Mango Trees: A Memoir of a Childhood in India. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307517692 – via Google Books.

- "The Tribune - Magazine section - Windows". www.tribuneindia.com.

- Balasubramaniam, Chitra (2 February 2013). "Food Safari: In search of Murthal Paratha The Hindu newspaper, 2-Feb-2013". The Hindu.

- "Highway Bites: Dhabas Vs food chains - Times of India". The Times of India. 6 September 2015.