Triangular trade

Triangular trade or triangle trade is trade between three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. It has been used to offset trade imbalances between different regions.

The Atlantic slave trade used a system of three-way transatlantic exchanges – known historically as the triangular trade – which operated between Europe, Africa, and the Americas from the 16th to 19th centuries. Slave ships were outfitted in Europe, and shipped manufactured European goods to West Africa to buy slaves for sale in the Americas, where ship holds were filled with American commodities for Europe. This trade, in trade volume, was primarily with South America but a classic example developed in 20th century study of the triangular trade is the colonial molasses trade, which involved the circuitous trading of slaves, sugar (often in liquid form, as molasses), and rum between West Africa, the West Indies and the northern colonies of British North America in the 17th and 18th centuries.[1][2] The slaves grew the sugar that was used to brew rum, which in turn was traded for more slaves. In this circuit, the sea lane west from Africa to the West Indies (and later, also to Brazil) was known as the Middle Passage; its cargo consisted of abducted or recently purchased African people. Slaves were often traded among Africa and Europe in exchange for European manufactured goods.

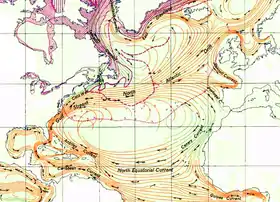

During the Age of Sail, the particular routes were also shaped by the powerful influence of winds and currents. For example, from the main trading nations of Western Europe, it was much easier to sail westwards after first going south of 30° N latitude and reaching the so-called "trade winds", thus arriving in the Caribbean rather than going straight west to the North American mainland. Returning from North America, it was easiest to follow the Gulf Stream in a northeasterly direction using the westerlies (Even before the voyages of Christopher Columbus, the Portuguese had been using a similar triangle to sail to the Canary Islands and the Azores, and it was then expanded outwards.).

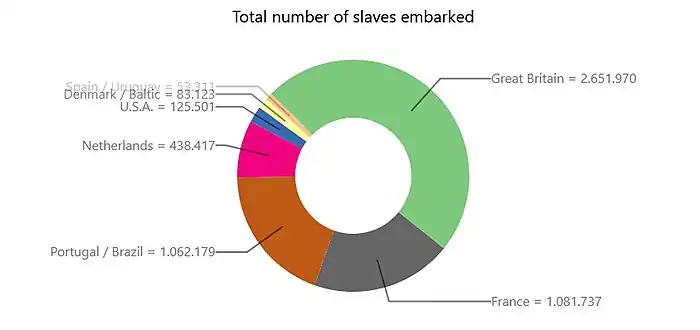

The countries that controlled the transatlantic slave market until the 18th century in terms of the number of enslaved people shipped were the United Kingdom, Portugal, and France.

Atlantic triangular slave trade

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

The most historically significant triangular trade was the transatlantic slave trade which operated between Europe, Africa, and the Americas from the 16th to 19th centuries. Slave ships would leave European ports (such as Bristol and Nantes) and sail to African ports loaded with goods manufactured in Europe. There, the slave traders would purchase enslaved Africans by exchanging the goods, then sail to the Americas via the Middle Passage to sell their enslaved cargo in European colonies. In what was referred to as a "golden triangle", the slave ship would sail back to Europe to begin the cycle again.[3] The enslaved Africans were primarily purchased for the purpose of working on plantations to work producing valuable cash crops (such as sugar, cotton, and tobacco) which were in high demand in Europe.[4][5][6][7][8] Slave traders from European colonies would occasionally travel to Africa themselves, eliminating the European portion of the voyage.[9][10]

A classic example is the colonial molasses trade. Merchants purchased raw sugar (often in its liquid form, molasses) from plantations in the Caribbean and shipped it to New England and Europe, where it was sold to distillery companies that produced rum. Merchant capitalists used cash from the sale of sugar to purchase rum, furs, and lumber in New England which their crews shipped to Europe. With the profits from the European sales, merchants purchased Europe's manufactured goods, including tools and weapons and on the next leg, shipped those manufactured goods, along with the American sugar and rum, to West Africa where they bartered the goods for slaves seized by local potentates. The crews then transported the slaves to the Caribbean and sold them to sugar plantation owners. The cash from the sale of slaves in Brazil, the Caribbean islands, and the American South used to buy more raw materials, restarting the cycle. The full triangle trip took a calendar year on average, according to historian Clifford Shipton.[11]

The first leg of the triangle was from a European port to one in West Africa (then known as the "Slave Coast"), in which ships carried supplies for sale and trade, such as copper, cloth, trinkets, slave beads, guns and ammunition.[12] When the ship arrived, its cargo would be sold or bartered for slaves. Ports that exported these enslaved people from Africa include Ouidah, Lagos, Aného (Little Popo), Grand-Popo, Agoué, Jakin, Porto-Novo, and Badagry.[13] These ports traded slaves who were supplied from African communities, tribes and kingdoms, including the Alladah and Ouidah, which were later taken over by the Dahomey kingdom.[14]

On the second leg, ships made the journey of the Middle Passage from Africa to the New World. Many slaves died of disease in the crowded holds of the slave ships. Once the ship reached the New World, enslaved survivors were sold in the Caribbean or the American colonies. The ships were then prepared to get them thoroughly cleaned, drained, and loaded with export goods for a return voyage, the third leg, to their home port,[15] from the West Indies the main export cargoes were sugar, rum, and molasses; from Virginia, tobacco and hemp. The ship then returned to Europe to complete the triangle.

The triangle route was not generally followed by individual ships. Slave ships were built to carry large numbers of people, rather than cargo, and variations in the duration of the Atlantic crossing meant that they often arrived in the Americas out-of-season. Slave ships thus often returned to their home port carrying whatever goods were readily available in the Americas but with a large part or all of their capacity with ballast.[16][17] Cash crops were transported mainly by a separate fleet which only sailed from Europe to the Americas and back.[18] In his books, Herbert S. Klein has argued that in many fields (cost of trade, ways of transport, mortality levels, earnings and benefits of trade for the Europeans and the "so-called triangular trade"), the non-scientific literature portrays a situation which the contemporary historiography refuted a long time ago.[19]

A 2017 study provides evidence for the hypothesis that the export of gunpowder to Africa increased the transatlantic slave trade: "A one percent increase in gunpowder set in motion a 5-year gun-slave cycle that increased slave exports by an average of 50%, and the impact continued to grow over time."[20]

New England

New England also made rum from Caribbean sugar and molasses, which it shipped to Africa as well as within the New World.[21] Yet, the "triangle trade" as considered in relation to New England was a piecemeal operation. No New England traders are known to have completed a sequential circuit of the full triangle, which took a calendar year on average, according to historian Clifford Shipton.[11] The concept of the New England Triangular trade was first suggested, inconclusively, in an 1866 book by George H. Moore, was picked up in 1872 by historian George C. Mason, and reached full consideration from a lecture in 1887 by American businessman and historian William B. Weeden.[11]

In the context of an incohesive operation rather than a sequential circuit, expansive eastern seaboard "Farms" had, in earnest after 1690, sustained southern New England proprietorship, land banks, and currency within a Greater Caribbean plantation complex. Historian Sean Kelley examines nineteenth-century "American slavers" because "the North American transatlantic slave trade before 1776 was, in essence, merely another branch of the carrying trade."[22][23] During the seventeenth century, colonial charters and royal commissioners precluded earlier attempts to establish a New England carrying trade by, for example, the Atherton Trading Company and John Hull. But proposals by Peleg Sanford provided implementation frameworks for "Farms" and carriers. Linkages within the complex would also ebb and flow with the tides of war and hurricanes. Before 1780, the Atlantic hurricane season contributed to New England and Greater Caribbean circumvention of mercantile trade restrictions. Newport carriers, for instance, provisioned Dutch, Danish, and especially French plantations in the Greater Caribbean, periodically more than lackluster British sites, to recompense for hurricane reductions in exports and imports.[24] Periodic trials and executions of notorious smugglers diminshed royal peacetime embargoes, particularly in response to illegal carrying as well as General Assembly endorsement of Aquidneck as a haven for pirates. These pirates began to disperse from Newport between Queen Anne's War and 1723 mass executions, establishing the seaport as the dominant carrying hub, with Providence coming in a distant second. British carriers continued to provision plantations outside the boundaries of empire.[25][26]

Wartime embargoes that reduced overseas trade would, in turn, spur speculative ventures as well as land and estuary auctions of Narragansett tribal reserves, under legislature (public) jurisdiction, by private trusts, a specific type of fiduciary relationship for subsidizing expense accounts, purveying regular annuities, or both. Bidders at vendue were frequently interior "composite"[27] yeomen and fishermen,[28] who (according to certain historians) misconceived[29] of revenue derived from the carrying trade as income "competency." Bidders included competitive carriers in secondary seaports such as Providence as well.[30] Despite the antebellum rise of "Greater Northeast" industrial agriculture,[31] the southern New England "Farms" and the carrying trade[32] in Caribbean sugar, molasses, rice, coffee, indigo, mahogany, and pre-1740 "seasoned slaves",[33] began to dissipate by the Election of 1800[34] and largely collapsed into agrarian ruins by the War of 1812.[35]

Newport and Bristol, Rhode Island, were major ports involved in the colonial triangular slave trade.[36] Many significant Newport merchants and traders participated in the trade, working closely with merchants and traders in the Caribbean and Charleston, South Carolina.[37]

Statistics

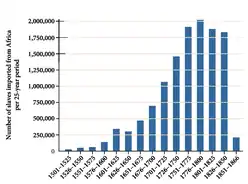

According to research provided by Emory University[38] as well as Henry Louis Gates Jr., an estimated 12.5 million slaves were transported from Africa to colonies in North and South America. The website Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database assembles data regarding past trafficking in slaves from Africa. It shows that the top four nations were Portugal, Great Britain, France, and Spain.

| Flag of vessels carrying the slaves | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destination | Portuguese | British | French | Spanish | Dutch | American | Danish | Total |

| Portuguese Brazil | 4,821,127 | 3,804 | 9,402 | 1,033 | 27,702 | 1,174 | 130 | 4,864,372 |

| British Caribbean | 7,919 | 2,208,296 | 22,920 | 5,795 | 6,996 | 64,836 | 1,489 | 2,318,251 |

| French Caribbean | 2,562 | 90,984 | 1,003,905 | 725 | 12,736 | 6,242 | 3,062 | 1,120,216 |

| Spanish Americas | 195,482 | 103,009 | 92,944 | 808,851 | 24,197 | 54,901 | 13,527 | 1,292,911 |

| Dutch Americas | 500 | 32,446 | 5,189 | 0 | 392,022 | 9,574 | 4,998 | 444,729 |

| United States | 382 | 264,910 | 8,877 | 1,851 | 1,212 | 110,532 | 983 | 388,747 |

| Danish West Indies | 0 | 25,594 | 7,782 | 277 | 5,161 | 2,799 | 67,385 | 108,998 |

| Europe | 2,636 | 3,438 | 664 | 0 | 2,004 | 119 | 0 | 8,861 |

| Africa | 69,206 | 841 | 13,282 | 66,391 | 3,210 | 2,476 | 162 | 155,568 |

| did not arrive | 748,452 | 526,121 | 216,439 | 176,601 | 79,096 | 52,673 | 19,304 | 1,818,686 |

| Total | 5,848,266 | 3,259,443 | 1,381,404 | 1,061,524 | 554,336 | 305,326 | 111,040 | 12,521,339 |

Other triangular trades

The term "triangular trade" also refers to a variety of other trades.

- A triangular trade is hypothesized to have taken place among ancient East Greece (and possibly Attica), Kommos, and Egypt.[39]

- A trade pattern which evolved before the American Revolutionary War among Great Britain, the Colonies of British North America, and British colonies in the Caribbean. This typically involved exporting raw resources, such as fish (especially salt cod), agricultural produce or lumber, from British North American colonies to slaves and planters in the West Indies; sugar and molasses from the Caribbean; and various manufactured commodities from Great Britain.[40]

- The shipment of Newfoundland salt cod and corn from Boston in British vessels to southern Europe.[41] This also included the shipment of wine and olive oil to Britain.

- A new "sugar triangle" developed in the 1820s and 1830s whereby American ships took local produce to Cuba, then brought sugar or coffee from Cuba to the Baltic coast (Russian Empire and Sweden), then bar iron and hemp back to New England.[42]

Notes

- Emert, Phyllis (1995). Colonial triangular trade: an economy based on human misery. Carlisle, Massachusetts: Discovery Enterprises Ltd. ISBN 978-1-878668-48-6. OCLC 32840704.

- Merritt, J. E. (1960). "The Triangular Trade". Business History. Informa UK Limited. 3 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1080/00076796000000012. ISSN 0007-6791. S2CID 153930643.

- Gold, Susan Dudley (2006). United States V. Amistad: Slave Ship Mutiny. Marshall Cavendish. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-7614-2143-6.

- Weber, Jacques. "La traite négrière nantaise de 1763 à 1793" (PDF). Centre national de la recherche scientifique (in French).

- Vindt, Gérard; Consil, Jean-Michel (June 2013). "Nantes, Bordeaux et l'économie esclavagiste – Au XVIIIe siècle, les villes de Nantes et de Bordeaux profitent toutes deux de la "traite négrière" et de l'économie esclavagiste". Alternatives économiques. 325: 17–21.

- Morgan, Kenneth (2007). Slavery and the British Empire: From Africa to America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780191566271. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Kowaleski-Wallace, A.P.o.E.E., Elizabeth (2006). The British slave trade and public memory. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231137140.

- Liverpool and the Slave Trade, by Anthony Tibbles, Director of the Merseyside Maritime Museum

- About.com: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Accessed 6 November 2007.

- "Triangular Trade". National Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011.

- Curtis, Wayne (2006–2007). And a Bottle of Rum. New York: Three Rivers Press. pp. 117-119 ISBN 978-0-307-33862-4.

- Scotland and the Abolition of the Slave Trade Archived 2012-01-03 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 28 March 2007.

- Mann, K (2007). "An African Family Archive: The Lawsons of Little Popo/Aneho (Togo), 1841-1938". The English Historical Review. CXXII (499): 1438–1439. doi:10.1093/ehr/cem350. ISSN 0013-8266.

- Lombard, J (2018). "The Kingdom of Dahomey". West African Kingdoms in the Nineteenth Century. Routledge. pp. 70–92. doi:10.4324/9780429491641-3. ISBN 978-0-429-49164-1. S2CID 204268220.

- A. P. Middleton, Tobacco Coast.

- Duquette, Nicolas J. (June 2014). "Revealing the Relationship Between Ship Crowding and Slave Mortality". The Journal of Economic History. 74 (2): 535–552. doi:10.1017/S0022050714000357. ISSN 0022-0507. S2CID 59449310.

- Wolfe, Brendan (1 February 2021). "Slave Ships and the Middle Passage". In Miller, Patti (ed.). Encyclopedia Virginia. Charlottesville, VA: Virginia Humanities – Library of Virginia. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Emmer, P.C.: The Dutch in the Atlantic Economy, 1580–1880. Trade, Slavery and Emancipation. Variorum Collected Studies Series CS614, 1998.

- Klein, H.S.:The Atlantic Slave Trade (Cambridge:The University of Cambridge, 1999)

- Whatley, Warren C. (2017). "The Gun-Slave Hypothesis and the 18th Century British Slave Trade" (PDF). Explorations in Economic History. 67: 80–104. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2017.07.001.

- "Slavery in Rhode Island". Slavery in the North. Accessed 11 September 2011.

- Kelley, Sean M. (30 May 2023). American Slavers: Merchants, Mariners, and the Transatlantic Commerce in Captives, 1644-1865. Yale University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-300-27155-3.

- Oakes, James (September 2023). "Ships Going Out". New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504.

- Schwartz, Stuart B. (2016). Sea of Storms: A History of Hurricanes in the Greater Caribbean from Columbus to Katrina. Princeton University Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-691-17360-3.

- Burgess, Douglas R. (2012). "A Crisis of Charter and Right: Piracy and Colonial Resistance in Seventeenth-Century Rhode Island". Journal of Social History. 45 (3): 605–622. ISSN 0022-4529.

- Hanna, Mark G. (22 October 2015). Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570-1740. UNC Press Books. pp. 365–392. ISBN 978-1-4696-1795-4.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (1998). "Markets and Composite Farms in Early America". The William and Mary Quarterly. 55 (3): 351–374. ISSN 0043-5597.

- Kulik, Gary (1985). "Dams, Fishes, and Farmers: Defense of Public Rights in Eighteenth-Century Rhode Island". The Countryside in the Age of Capitalist Transformation: Essays in the Social History of Rural America. University of North Carolina Press (Chapel Hill): 25–50.

- Kulikoff, Allan (1 February 2014). From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers. Chapel Hill: Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 104 and 207. ISBN 978-0-8078-6078-6.

- Vickers, Daniel (1990). "Competency and Competition: Economic Culture in Early America". The William and Mary Quarterly. 47 (1): 3–29. doi:10.2307/2938039. ISSN 0043-5597.

- Ron, Ariel (2020). Grassroots Leviathan: Agricultural Reform and the Rural North in the Slaveholding Republic. JHU Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4214-3932-7.

- Clark-Pujara, Christy (2016). Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. NYU Press. pp. 24–27. ISBN 978-1-4798-7042-4.

- O'Malley, Gregory E. (2014). Final Passages: The Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America, 1619-1807. UNC Press Books. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-4696-1535-6.

- Clark-Pujara, Christy (2016). Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. NYU Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-4798-7042-4.

- Taylor, Alan (2010). The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, and Indian Allies. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 31 and 119. ISBN 978-1-4000-4265-4.

- "The Unrighteous Traffick". The Providence Journal. March 12, 2006. Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- Deutsch, Sarah (1982). "The Elusive Guineamen: Newport Slavers, 1735–1774". The New England Quarterly. 55 (2): 229–253. doi:10.2307/365360. JSTOR 365360.

- Slave Voyages, Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Estimates

- Jones, Donald W.; Archaeological Institute of America; University of Pennsylvania. University Museum (2000). "Crete's External Relations in the Early Iron Age". External relations of early Iron Age Crete, 1100–600 B.C. p. 97. ISBN 9780924171802.

- Kurlansky, Mark. Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World. New York: Walker, 1997. ISBN 0-8027-1326-2.

- Morgan, Kenneth. Bristol and the Atlantic Trade in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-33017-3. pp. 64–77.

- Chris Evans and Göran Rydén, Baltic Iron in the Atlantic World in the Eighteenth Century : Brill, 2007 ISBN 978-90-04-16153-5, 273.

External links

- The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, a portal to data concerning the history of the triangular trade of transatlantic slave trade voyages.

- Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice