Texas Equal Suffrage Association

The Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) was an organization founded in 1903 to support white women's suffrage in Texas. It was originally formed under the name of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association (TWSA) and later renamed in 1916. TESA did allow men to join.[1] TESA did not allow black women as members, because at the time to do so would have been "political suicide."[2] The El Paso Colored Woman's Club applied for TESA membership in 1918, but the issue was deflected and ended up going nowhere.[3] TESA focused most of their efforts on securing the passage of the federal amendment for women's right to vote.[4] The organization also became the state chapter of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).[1] After women earned the right to vote, TESA reformed as the Texas League of Women Voters.[5]

| Abbreviation | TESA |

|---|---|

| Successor | Texas League of Women Voters |

| Formation | 1903 |

| Founded at | Houston, Texas |

| Dissolved | 1919 |

| Type | Non-governmental organization |

| Purpose | Woman's suffrage |

| Affiliations | National American Woman Suffrage Association |

| Elections in Texas |

|---|

|

|

|

History

The predecessor of the Texas Equal Suffrage Association was the Texas Equal Rights Association (TERA) which was organized in Dallas in May 1893 by Rebecca Henry Hayes of Galveston. [6] TERA had auxiliaries in Beaumont, Belton, Dallas, Denison, Fort Worth, Granger, San Antonio, and Taylor.[6] TERA was active until 1895.[6]

Suffragists in Texas formed the Texas Woman Suffrage Association (TWSA) in 1903[7] and renamed it the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) in 1916. Annette Finnigan and her sisters, Elizabeth and Katharine, organized the Equal Suffrage League of Houston in February 1903 after Carrie Chapman Catt gave a lecture in the city.[8][6] Suffragists in Galveston soon established a similar organization.[9] In December 1903, delegates from the two organizations met in Houston and organized the Texas Woman Suffrage Association with Annette Finnigan as the first president.[9] During Finnigan’s presidency, the sisters attempted to organize women’s suffrage leagues in other cities but found little support.[9] The organization also worked unsuccessfully to have a woman appointed to the Houston school board.[10] When the Finnigan sisters moved from Texas in 1905, the association became inactive.[8] Between 1905 and 1912, there was little suffrage activity in Texas except for a local league that suffragists in Austin organized in 1908[8] but which never affiliated with the NAWSA. [11]

A resurgence of interest in women's suffrage took place when Anna Howard Shaw, the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, toured Texas in 1912.[12] In February 1912, suffragists in San Antonio formed an Equal Franchise Society with Mary Eleanor Brackenridge, a prominent clubwoman and civic leader, as president. The San Antonio organization was very active with frequent meetings, public lectures and the distribution of literature.[12] Annette Finnigan, who had returned to Houston in 1909, also began to form local suffrage groups in 1912.[10] Brackenridge was responsible for reorganizing TWSA in 1913.[13] In April of that year, 100 Texans met in San Antonio to reactivate TWSA[14] with seven local chapters sending delegates.[15] The delegates elected Brackenridge as president. Annette Finnigan succeeded Brackenridge as president in 1914, followed by Minnie Fisher Cunningham from Galveston in 1915.[12][15]

The Texas Woman Suffrage Association had three objectives: 1) support the national agenda as defined by NAWSA, 2) lobby for a state suffrage amendment, and 3) assist local groups in promoting the cause of women’s suffrage. Texas suffragists, like those in other southern states, were conflicted between fighting for an amendment to the state constitution or advocating for the Susan B. Anthony amendment to the U.S. constitution.[16] When Brackenridge became president of the TWSA in 1913, she began to correspond with Texas legislators about amending the Texas constitution to grant women the vote.[17] In 1915, Finnigan and others continued this effort by lobbying state legislators for a state constitutional amendment and came within two votes of achieving the vote for women that year.[18] After that, TWSA leadership increasingly followed the lead of the NAWSA and focused on achieving the passage of the federal amendment. [19]

In April 1915, Minnie Fisher Cunningham was elected president of the TWSA at the state convention in Galveston.[20] Cunningham was reelected each year until TESA evolved into the Texas League of Women Voters in October 1919.[21][22] When Cunningham became president, there were 21 local chapters of the TWSA and about 2,500 members. By 1917, there were 98 local chapters.[23] Cunningham led the TWSA in adopting the precinct-by-precinct organizing strategy developed by New York City suffragists.[24] Under her tenure, TWSA received support from the Federation of Women's Clubs, the Texas Farm Women, Texas Press Women and the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).[2] In 1915, the Texas Association of Women's Clubs, which was the umbrella organization of African American women's clubs in Texas, endorsed women's suffrage.[25] The endorsement of women’s suffrage by the Texas Federation of Women’s Clubs especially helped make the movement respectable to many middle-class women.[26]

In May 1916, the organization changed its name to the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA).[27] In 1917, the headquarters of TESA was moved from Houston to Austin.[28] When Texas Governor James E. Ferguson, an opponent of women's suffrage, was indicted on various charges including embezzlement in 1917, TESA supported his impeachment.[29] When the United States entered World War I in 1917, TESA used the momentum of patriotism to point out how women contributed to the war effort.[30] During the war, TESA urged members to contribute to the war effort including creating victory gardens, purchasing thrift stamps and selling war bonds.[31] As the president of TESA, Cunningham was quick to point out that immigrants, especially German Americans, were allowed to vote, but Texas men at war were disenfranchised and their mothers and wives were not able to represent them at the polls through the ballot.[32]

In 1918, TESA led the effort to get women the vote in state primary elections.[33] In seventeen days, TESA and other suffrage organizations registered approximately 386,000 Texas women to vote.[1] After Texas women were granted the primary vote in March 1918, TESA turned its attention to lobbying its federal representatives to support the Susan B. Anthony amendment to the federal constitution.[29] In June 1919, Texas became the first state in the South to ratify the federal suffrage amendment.[29] Both Texas senators and ten of eighteen U.S. representatives from Texas voted for the federal amendment.[29]

On October 10, 1919, TESA reorganized as the Texas League of Women Voters with Jessie Daniel Ames as the first president.[34]

Austin Women Suffrage Association

The Austin Women Suffrage Association (AWSA) was founded on December 4, 1908 and served as an auxiliary of TESA.[35][36] Jane Y. McCallum served as president of AWSA starting in 1915.[37]

Notable members

- Jessie Daniel Ames

- Carrie Chapman Catt

- Mary Eleanor Brackenridge, president in 1913.

- Minnie Fisher Cunningham, president in 1915

- Jane Y. McCallum[38]

References

Citations

- Humphrey, Janet G. (15 June 2010). "Texas Equal Suffrage Association". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.

- McArthur & Smith 2010, p. 135.

- "Timeline". Women in Texas History. Ruthe Winegarten Memorial Foundation for Texas Women. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Taking it to the Voters". The Battle Lost -- And Won. Texas State Library and Archives Commission. 24 August 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Local Leagues", Lwv.org, retrieved August 15, 2020

- HUMPHREY, JANET G. (2010-06-15). "TEXAS EQUAL SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION". tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- "Taking it to the Voters". The Battle Lost -- And Won. Texas State Library and Archives Commission. 24 August 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Dorothy Brown, “Sixty Five Going on Fifty: A History of the League of Women Voters of Texas, 1903-1969.” Manuscript. League of Women Voters files, Austin, 1969. Page 1. Accessed on www.my.lwv.org/texas/history 4.13.2019.

- Humphrey, Janet G. (15 June 2010). "Texas Equal Suffrage Association". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.

- Scott 2014, p. 7.

- Seymour, James. “Fighting on the Homefront: The Rhetoric of Woman Suffrage in World War I.” in Debra A. Reid, ed. Seeking Inalienable Rights: Texans and Their Quests for Justice. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2009.

- Humphrey, Janet G. (15 June 2010). "Texas Equal Suffrage Association". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.

- McArthur & Smith 2010, p. 134-135.

- Taylor, A. Elizabeth (31 August 2010). "Woman Suffrage". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- HUMPHREY, JANET G. (2010-06-15). "TEXAS EQUAL SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION". tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- Brannon-Wranosky, Jessica S. “Southern Promise and Necessity: Texas, Regional Identity, and the National Woman Suffrage Movement, 1868-1920.” Unpublished dissertation. University of North Texas, August 2010. Page 177.

- Brandenstein, Sherilyn (12 June 2010). "Finnigan, Annette". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- Humphrey, Janet G. (15 June 2010). "Texas Equal Suffrage Association". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.

- Brannon-Wranosky, Jessica S. “Southern Promise and Necessity: Texas, Regional Identity, and the National Woman Suffrage Movement, 1868-1920.” Unpublished dissertation. University of North Texas, August 2010. Page 179.

- HUMPHREY, JANET G. (2010-06-15). "TEXAS EQUAL SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION". tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- Dorothy Brown, “Sixty Five Going on Fifty: A History of the League of Women Voters of Texas, 1903-1969.” Manuscript. League of Women Voters files, Austin, 1969. Page 1. Accessed on www.my.lwv.org/texas/history 4.13.2019.

- Taylor, A. Elizabeth (31 August 2010). "Woman Suffrage". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "The Early Years". Jane McCallum and the Suffrage Movement. Austin Public Library. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Hall 1993, p. 25.

- “Texas Association of Women’s Clubs,” Texas Woman’s University: Woman’s Collection. www.twudigital.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/p16283coll10. Accessed April 19, 2019.

- Seymour, James. “Fighting on the Homefront: The Rhetoric of Woman Suffrage in World War I.” in Debra A. Reid, ed. Seeking Inalienable Rights: Texans and Their Quests for Justice. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2009.

- Taylor, A. Elizabeth (31 August 2010). "Woman Suffrage". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "The Early Years". Jane McCallum and the Suffrage Movement. Austin Public Library. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Bates, Steph (March 2009). "Remembering a Texas Suffragist". Humanities Texas. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Seymour 2009, p. 65-66.

- Seymour 2009, p. 66-67.

- Seymour 2009, p. 69-70.

- Gregory, Elizabeth (25 August 2013). "Women's Suffrage Texas-Style". The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Hall 1993, p. 44.

- "Jane McCallum and the Suffrage Movement". Austin History Center. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- "A Guide to the Austin Women's Suffrage Association Records, 1908-1915". Texas Archival Resources Online. Austin Women’s Suffrage Association. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Texas Originals - Jane Y. McCallum". Humanities Texas. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- Turner, Elizabeth Hayes; Cole, Stephanie; Sharpless, Rebecca (2015). Texas Women: Their Histories, Their Lives. University of Georgia Press. pp. 264. ISBN 9780820337449.

jane y mccallum.

Sources

- Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd (1993). Revolt Against Chivalry. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231082839.

- McArthur, Judith N. (1998). Creating the New Woman: The Rise of Southern Women's Progressive Culture in Texas, 1893-1918. University of Illinois Press. p. 197. ISBN 9780252066795.

texas equal rights association.

- McArthur, Judith N.; Smith, Harold L. (2010). "Not Whistling Dixie: Women's Movements and Feminist Politics". In Cullen, David O'Donald; Wilkinson, Kyle G. (eds.). The Texas Left: The Radical Roots of Lone Star Liberalism. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9781603441896.

- Scott, Janelle D. (June 2014). "Local Leadership in the Woman Suffrage Movement: Houston's Campaign for the Vote 1917-1918" (PDF). The Houston Review: 3–22. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- Seymour, James (2009). "Fighting on the Home Front: The Rhetoric of Woman Suffrage in World War I". In Reid, Debra Ann (ed.). Seeking Inalienable Rights: Texans and Their Quests for Justice. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9781603443630.

External links

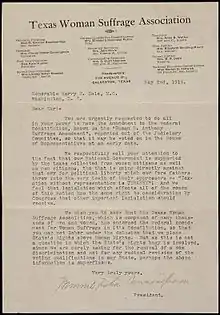

- Texas Woman Suffrage Association petition (May 2, 1916)