Bassa language

The Bassa language is a Kru language spoken by about 600,000 Bassa people in Liberia, Ivory Coast, and Sierra Leone.

| Bassa | |

|---|---|

| Ɓǎsɔ́ɔ̀ (𖫢𖫧𖫳𖫒𖫨𖫰𖫨𖫱) | |

| Native to | Liberia, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone |

Native speakers | 410,000 (2006)[1] |

| Bassa Vah alphabet (Vah) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | bsq |

| Glottolog | nucl1418 |

Phonology

Bassa alphabets

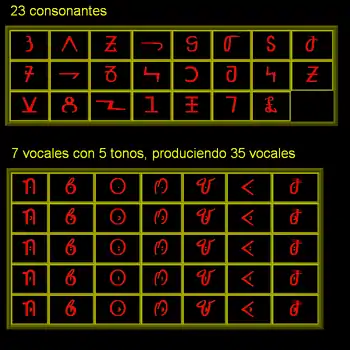

It has an indigenous alphabet, Vah, first popularized by Thomas Flo Lewis, who has instigated publishing of limited materials in the language from the mid-1900s through the 1930s, with its height in the 1910s and 1920s.[3] It has been reported that the alphabet was influenced by the Cherokee syllabary created by Sequoyah.[4]

The Vah alphabet has been described as one which, "like the system long in use among the Vai, consists of a series of phonetic characters standing for syllables."[5] In fact, however, Vah is alphabetic. It includes 30 consonants, seven vowels, and five tones that are indicated by dots and lines inside each vowel.

In the 1970s the United Bible Societies (UBS) published a translation of the New Testament. June Hobley, of Liberia Inland Mission, was primarily responsible for the translation. The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) was used for this translation rather than the Vah alphabet, mostly for practical reasons related to printing. Because the Bassa people had a tradition of writing, they quickly adapted to the new alphabet, and thousands learned to read.

In 2005, UBS published the entire Bible in Bassa. The translation was sponsored by the Christian Education Foundation of Liberia, Christian Reformed World Missions, and UBS. Don Slager headed a team of translators that included Seokin Payne, Robert Glaybo, and William Boen.

The IPA has largely replaced the Vah alphabet in publications. However, Vah is still highly respected and is still in use by some older men, primarily for record keeping.

Letters

- A - a - [a]

- B - be - [b]

- Ɓ - ɓe - [ɓ/ⁿb]

- C - ce - [c]

- D - de - [d]

- Đ - ɖe - [ɖ/ɺ]

- Dy - dye - [dʲ/ɲ]

- Ɛ - ɛ - [ɛ]

- E - e - [e]

- F - ef - [f]

- G - ge - [g]

- Gb - gbe - [ɡ͡b/ŋ͡m]

- Gm - gme - [g͡m]

- H - ha - [h]

- Hw - hwa - [hʷ]

- I - i - [i]

- J - je - [ɟ]

- K - ka - [k]

- Kp - kpe - [k͡p]

- M - em - [m]

- N - en - [n]

- Ny - eny - [ŋ]

- Ɔ - ɔ - [ɔ]

- O - o - [o]

- P - pe - [p]

- S - es - [s]

- T - te - [t]

- U - u - [u]

- V - ve - [v]

- W - we - [w]

- Xw - xwa - [xʷ]

- Z - ze - [z]

Other letters

- ã - [ã]

- ẽ - [ẽ]

- ĩ - [ĩ]

- ɔ̃ - [ɔ̃]

- ũ - [ũ]

Some Bassa speakers write nasalised vowels as an, en, in, ɔn, and un.

Tones

- á - [a˥]

- à - [a˨]

- a - [a˧]

- ǎ - [a˨˧]

- â - [a˥˩][6]

References

- Bassa at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Bertkau, Jana S. (1975). A phonology of Bassa. Monrovia: Peace Corps.

- "Bassa language and alphabet". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 2020-02-27.

- Unseth, Peter (20 December 2016). "The international impact of Sequoyah's Cherokee syllabary". Written Language & Literacy. 19 (1): 75–93. doi:10.1075/wll.19.1.03uns.

- Starr, Frederick. Liberia: Description, history, problems. Chicago, 1913. P.246

- "Bassa language and alphabet". Omniglot.

External links

- Omniglot: Bassa alphabet

- Bassa-English Dictionary

- Brief Summary of Liberian Indigenous Scripts

- Gbokpasom - Non-Profit