Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg (locally /ˈɡɛtɪsbɜːrɡ/ ⓘ)[13] was a battle in the American Civil War fought by Union and Confederate forces between July 1 and July 3, 1863, in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

| Battle of Gettysburg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern theater of the American Civil War | |||||||

The Battle of Gettysburg by Thure de Thulstrup | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George Meade | Robert E. Lee | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Potomac[2] | Army of Northern Virginia[3] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

93,500–104,256[4][5] 360 artillery pieces 36 cavalry regiments |

71,000–75,000, possibly as many as 80,000.[6] 270 artillery pieces 9,500 cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 23,049[7][8] | 23,000–28,000[9][10] | ||||||

%252C_by_Harper's_Weekly.jpg.webp)

In the Battle of Gettysburg, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Potomac defeated attacks by Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, halting Lee's invasion of the North and forcing his retreat. The battle involved the largest number of casualties of the entire war and is often described as the war's turning point, due to the Union's decisive victory and its almost simultaneous concurrence with the victorious conclusion of the Siege of Vicksburg.[fn 1][14]

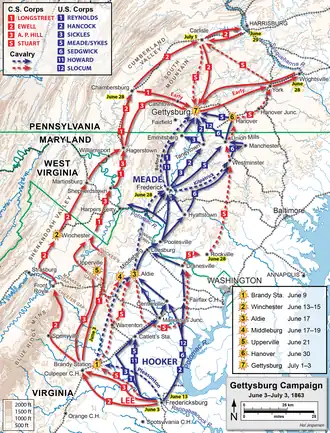

After his success at Chancellorsville in Virginia in May 1863, Lee led his army through the Shenandoah Valley to begin his second invasion of the North—the Gettysburg Campaign. With his army in high spirits, Lee intended to shift the focus of the summer campaign from war-ravaged northern Virginia and hoped to influence Northern politicians to give up their prosecution of the war by penetrating as far as Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, or even Philadelphia. Prodded by President Abraham Lincoln, Major General Joseph Hooker moved his army in pursuit, but was relieved of command just three days before the battle and replaced by Meade.

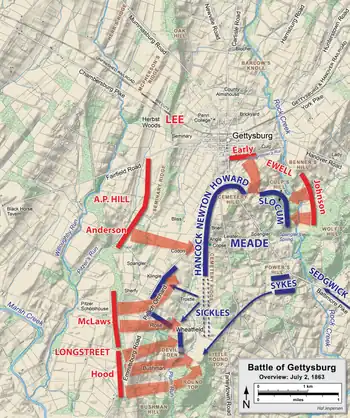

Elements of the two armies initially collided at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, as Lee urgently concentrated his forces there, his objective being to engage the Union army and destroy it. Low ridges to the northwest of town were defended initially by a Union cavalry division under Brigadier General John Buford, and soon reinforced with two corps of Union infantry. However, two large Confederate corps assaulted them from the northwest and north, collapsing the hastily developed Union lines, sending the defenders retreating through the streets of the town to the hills just to the south.[15] On the second day of battle, most of both armies had assembled. The Union line was laid out in a defensive formation resembling a fishhook. In the late afternoon of July 2, Lee launched a heavy assault on the Union left flank, and fierce fighting raged at Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, Devil's Den, and the Peach Orchard. On the Union right, Confederate demonstrations escalated into full-scale assaults on Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. All across the battlefield, despite significant losses, the Union defenders held their lines.

On the third day of battle, fighting resumed on Culp's Hill, and cavalry battles raged to the east and south, but the main event was a dramatic infantry assault by around 12,000 Confederates against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, known as Pickett's Charge. The charge was repelled by Union rifle and artillery fire, at great loss to the Confederate army. Lee led his army on the torturous Retreat from Gettysburg to Virginia. Between 46,000 and 51,000 soldiers from both armies were casualties in the three-day battle, the most costly in US history. On November 19, President Lincoln used the dedication ceremony for the Gettysburg National Cemetery to honor the fallen Union soldiers and redefine the purpose of the war in his historic Gettysburg Address.

Background

Military situation

Shortly after the Army of Northern Virginia won a major victory over the Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Chancellorsville (April 30 – May 6, 1863), General Robert E. Lee decided upon a second invasion of the North (the first was the unsuccessful Maryland campaign of September 1862, which ended in the bloody Battle of Antietam). Such a move would upset the Union's plans for the summer campaigning season and possibly reduce the pressure on the besieged Confederate garrison at Vicksburg. The invasion would allow the Confederates to live off the bounty of the rich Northern farms while giving war-ravaged Virginia a much-needed rest. In addition, Lee's 72,000-man army[6] could threaten Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and possibly strengthen the growing peace movement in the North.[16]

Initial movements to battle

Thus, on June 3, Lee's army began to shift northward from Fredericksburg, Virginia. Following the death of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, Lee reorganized his two large corps into three new corps, commanded by Lieutenant General James Longstreet (First Corps), Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell (Second), and Lieutenant General A.P. Hill (Third); both Ewell and Hill, who had formerly reported to Jackson as division commanders, were new to this level of responsibility. The cavalry division remained under the command of Major General J.E.B. Stuart.[17]

The Union Army of the Potomac under Major General Joseph Hooker consisted of seven infantry corps, a cavalry corps, and an artillery reserve, for a combined strength of more than 100,000 men.[5]

The first major action of the campaign took place on June 9 between cavalry forces at Brandy Station, near Culpeper, Virginia. The 9,500 Confederate cavalrymen under Stuart were surprised by Major General Alfred Pleasonton's combined arms force of two cavalry divisions (8,000 troopers) and 3,000 infantry, but Stuart eventually repelled the Union attack. The inconclusive battle, the largest predominantly cavalry engagement of the war, proved for the first time that the Union horse soldier was equal to his Southern counterpart.[18]

By mid-June, the Army of Northern Virginia was poised to cross the Potomac River and enter Maryland. After defeating the Union garrisons at Winchester and Martinsburg, Ewell's Second Corps began crossing the river on June 15. Hill's and Longstreet's corps followed on June 24 and 25. Hooker's army pursued, keeping between Washington, D.C., and Lee's army. The Union army crossed the Potomac from June 25 to 27.[19]

Lee gave strict orders for his army to minimize any negative effects on the civilian population.[20][21] Food, horses, and other supplies were generally not seized outright unless a citizen concealed property, although quartermasters reimbursing Northern farmers and merchants with Confederate money which was virtually worthless or with equally worthless promissory notes were not well received.[22] Various towns, most notably York, Pennsylvania, were required to pay indemnities in lieu of supplies, under threat of destruction.[23] During the invasion, the Confederates seized between 40 and nearly 60 northern African Americans. A few of them were escaped fugitive slaves, but many were freemen; all were sent south into slavery under guard.[11][12]

On June 26, elements of Major General Jubal Early's division of Ewell's corps occupied the town of Gettysburg after chasing off newly raised Pennsylvania militia in a series of minor skirmishes. Early laid the borough under tribute, but did not collect any significant supplies. Soldiers burned several railroad cars and a covered bridge, and destroyed nearby rails and telegraph lines. The following morning, Early departed for adjacent York County.[24]

Meanwhile, in a controversial move, Lee allowed Stuart to take a portion of the army's cavalry and ride around the east flank of the Union army. Lee's orders gave Stuart much latitude, and both generals share the blame for the long absence of Stuart's cavalry, as well as for the failure to assign a more active role to the cavalry left with the army. Stuart and his three best brigades were absent from the army during the crucial phase of the approach to Gettysburg and the first two days of battle. By June 29, Lee's army was strung out in an arc from Chambersburg (28 mi (45 km) northwest of Gettysburg) to Carlisle (30 mi (48 km) north of Gettysburg) to near Harrisburg and Wrightsville on the Susquehanna River.[25]

In a dispute over the use of the forces defending the Harpers Ferry garrison, Hooker offered his resignation, and Abraham Lincoln and General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck, who were looking for an excuse to rid themselves of him, immediately accepted. They replaced Hooker early on the morning of June 28 with Major General George Gordon Meade, then commander of the V Corps.[26]

On June 29, when Lee learned that the Army of the Potomac had crossed the Potomac River, he ordered a concentration of his forces around Cashtown, located at the eastern base of South Mountain and eight mi (13 km) west of Gettysburg.[27] On June 30, while part of Hill's corps was in Cashtown, one of Hill's brigades (North Carolinians under Brigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew) ventured toward Gettysburg. In his memoirs, Major General Henry Heth, Pettigrew's division commander, claimed that he sent Pettigrew to search for supplies in town—especially shoes.[28]

When Pettigrew's troops approached Gettysburg on June 30, they noticed Union cavalry under Major General John Buford arriving south of town, and Pettigrew returned to Cashtown without engaging them. When Pettigrew told Hill and Heth what he had seen, neither general believed that there was a substantial Union force in or near the town, suspecting that it had been only Pennsylvania militia. Despite Lee's order to avoid a general engagement until his entire army was concentrated, Hill decided to mount a significant reconnaissance in force the following morning to determine the size and strength of the enemy force in his front. Around 5 a.m. on Wednesday, July 1, two brigades of Heth's division advanced to Gettysburg.[29]

Opposing forces

Union

The Army of the Potomac, initially under Hooker (Meade replaced Hooker in command on June 28), consisted of more than 100,000 men in the following organization:[30]

- I Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. James S. Wadsworth, Brig. Gen. John C. Robinson, and Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday.

- II Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. John C. Caldwell, John Gibbon, and Alexander Hays.

- III Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gen. David B. Birney and Maj. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys.

- V Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Sykes (George G. Meade until June 28), with divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. James Barnes, Romeyn B. Ayres, and Samuel W. Crawford.

- VI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. Horatio G. Wright, Brig. Gen. Albion P. Howe, and Maj. Gen. John Newton.

- XI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow, Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr, and Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz.

- XII Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. Alpheus S. Williams and John W. Geary.

- Cavalry Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. John Buford, David McM. Gregg, and H. Judson Kilpatrick.

- Artillery Reserve, commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert O. Tyler. (The preeminent artillery officer at Gettysburg was Brig. Gen. Henry Jackson Hunt, chief of artillery on Meade's staff.)

During the advance on Gettysburg, Reynolds was in operational command of the left, or advanced, wing of the Army, consisting of the I, III, and XI Corps.[31] Many other Union units (not part of the Army of the Potomac) were actively involved in the Gettysburg Campaign, but not directly involved in the Battle of Gettysburg. These included portions of the Union IV Corps, the militia and state troops of the Department of the Susquehanna, and various garrisons, including that at Harpers Ferry.

Confederate

In reaction to the death of Jackson after Chancellorsville, Lee reorganized his Army of Northern Virginia (75,000 men) from two infantry corps into three.[32]

- First Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gens. Lafayette McLaws, George Pickett, and John Bell Hood.

- Second Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gens. Jubal A. Early, Edward "Allegheny" Johnson, and Robert E. Rodes.

- Third Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gens. Richard H. Anderson, Henry Heth, and W. Dorsey Pender.

- Cavalry division, commanded by Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart, with brigades commanded by Brig. Gens. Wade Hampton, Fitzhugh Lee, Beverly H. Robertson, Albert G. Jenkins, William E. "Grumble" Jones, and John D. Imboden, and Col. John R. Chambliss.

First day of battle

Herr Ridge, McPherson Ridge and Seminary Ridge

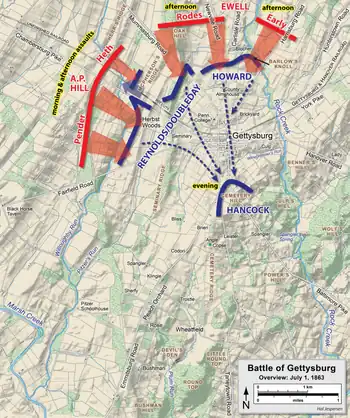

Anticipating that the Confederates would march on Gettysburg from the west on the morning of July 1, Buford laid out his defenses on three ridges west of the town: Herr Ridge, McPherson Ridge and Seminary Ridge. These were appropriate terrain for a delaying action by his small cavalry division against superior Confederate infantry forces, meant to buy time awaiting the arrival of Union infantrymen who could occupy the strong defensive positions south of town at Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and Culp's Hill. Buford understood that if the Confederates could gain control of these heights, Meade's army would have difficulty dislodging them.[33]

Heth's division advanced with two brigades forward, commanded by brigadier generals James J. Archer and Joseph R. Davis. They proceeded easterly in columns along the Chambersburg Pike. Three mi (5 km) west of town, about 7:30 a.m. on July 1, the two brigades met light resistance from vedettes of Union cavalry, and deployed into line. According to lore, the Union soldier to fire the first shot of the battle was Lt. Marcellus Jones.[34] Eventually Heth's men encountered dismounted troopers of Col. William Gamble's cavalry brigade. The dismounted troopers resisted stoutly, delaying the Confederate advance with most firing their breech-loading Sharp's carbines from behind fences and trees. (A small number of troopers had other carbine models. A small minority of historians have written that some troopers had Spencer repeating carbines or Spencer repeating rifles but most sources disagree.)[35][fn 2] Still, by 10:20 a.m., the Confederates had pushed the Union cavalrymen east to McPherson Ridge, when the vanguard of the I Corps (Major General John F. Reynolds) finally arrived.[36]

North of the pike, Davis gained a temporary success against Brigadier General Lysander Cutler's brigade but was repelled with heavy losses in an action around an unfinished railroad bed cut in the ridge. South of the pike, Archer's brigade assaulted through Herbst (also known as McPherson's) Woods. The Union Iron Brigade under Brigadier General Solomon Meredith enjoyed initial success against Archer, capturing several hundred men, including Archer himself.[37]

General Reynolds was shot and killed early in the fighting while directing troop and artillery placements just to the east of the woods. Shelby Foote wrote that the Union cause lost a man considered by many to be "the best general in the army".[38] Major General Abner Doubleday assumed command. Fighting in the Chambersburg Pike area lasted until about 12:30 p.m. It resumed around 2:30 p.m., when Heth's entire division engaged, adding the brigades of Pettigrew and Col. John M. Brockenbrough.[39]

As Pettigrew's North Carolina Brigade came on line, they flanked the 19th Indiana and drove the Iron Brigade back. The 26th North Carolina (the largest regiment in the army with 839 men) lost heavily, leaving the first day's fight with around 212 men. By the end of the three-day battle, they had about 152 men standing, the highest casualty percentage for one battle of any regiment, North or South.[40] Slowly the Iron Brigade was pushed out of the woods toward Seminary Ridge. Hill added Major General William Dorsey Pender's division to the assault, and the I Corps was driven back through the grounds of the Lutheran Seminary and Gettysburg streets.[41]

As the fighting to the west proceeded, two divisions of Ewell's Second Corps, marching west toward Cashtown in accordance with Lee's order for the army to concentrate in that vicinity, turned south on the Carlisle and Harrisburg roads toward Gettysburg, while the Union XI Corps (Major General Oliver O. Howard) raced north on the Baltimore Pike and Taneytown Road. By early afternoon, the Union line ran in a semicircle west, north, and northeast of Gettysburg.[42]

However, the Union did not have enough troops; Cutler, whose brigade was deployed north of the Chambersburg Pike, had his right flank in the air. The leftmost division of the XI Corps was unable to deploy in time to strengthen the line, so Doubleday was forced to throw in reserve brigades to salvage his line.[43]

Around 2:00 p.m., the Confederate Second Corps divisions of Maj. Gens. Robert E. Rodes and Jubal Early assaulted and out-flanked the Union I and XI Corps positions north and northwest of town. The Confederate brigades of Colonel Edward A. O'Neal and Brigadier General Alfred Iverson suffered severe losses assaulting the I Corps division of Brigadier General John C. Robinson south of Oak Hill. Early's division profited from a blunder by Brigadier General Francis C. Barlow, when he advanced his XI Corps division to Blocher's Knoll (directly north of town and now known as Barlow's Knoll); this represented a salient[44] in the corps line, susceptible to attack from multiple sides, and Early's troops overran Barlow's division, which constituted the right flank of the Union Army's position. Barlow was wounded and captured in the attack.[45]

As Union positions collapsed both north and west of town, Howard ordered a retreat to the high ground south of town at Cemetery Hill, where he had left the division of Brigadier General Adolph von Steinwehr in reserve.[46] Major General Winfield S. Hancock assumed command of the battlefield, sent by Meade when he heard that Reynolds had been killed. Hancock, commander of the II Corps and Meade's most trusted subordinate, was ordered to take command of the field and to determine whether Gettysburg was an appropriate place for a major battle.[47] Hancock told Howard, "I think this the strongest position by nature upon which to fight a battle that I ever saw." When Howard agreed, Hancock concluded the discussion: "Very well, sir, I select this as the battle-field." Hancock's determination had a morale-boosting effect on the retreating Union soldiers, but he played no direct tactical role on the first day.[48]

General Lee understood the defensive potential to the Union if they held this high ground. He sent orders to Ewell that Cemetery Hill be taken "if practicable". Ewell, who had previously served under Stonewall Jackson, a general well known for issuing peremptory orders, determined such an assault was not practicable and, thus, did not attempt it; this decision is considered by historians to be a great missed opportunity.[49]

The first day at Gettysburg, more significant than simply a prelude to the bloody second and third days, ranks as the 23rd biggest battle of the war by number of troops engaged. About one quarter of Meade's army (22,000 men) and one third of Lee's army (27,000) were engaged.[50]

Second day of battle

Plans and movement to battle

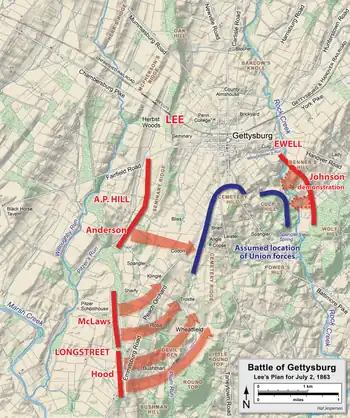

Throughout the evening of July 1 and morning of July 2, most of the remaining infantry of both armies arrived on the field, including the Union II, III, V, VI, and XII Corps. Two of Longstreet's divisions were on the road: Brigadier General George Pickett, had begun the 22-mile (35 km) march from Chambersburg, while Brigadier General Evander M. Law had begun the march from Guilford. Both arrived late in the morning. Law completed his 28-mile (45 km) march in eleven hours.[51]

The Union line ran from Culp's Hill southeast of the town, northwest to Cemetery Hill just south of town, then south for nearly two miles (3 km) along Cemetery Ridge, terminating just north of Little Round Top.[52] Most of the XII Corps was on Culp's Hill; the remnants of I and XI Corps defended Cemetery Hill; II Corps covered most of the northern half of Cemetery Ridge; and III Corps was ordered to take up a position to its flank. The shape of the Union line is popularly described as a "fishhook" formation.[53]

The Confederate line paralleled the Union line about one mile (1,600 m) to the west on Seminary Ridge, ran east through the town, then curved southeast to a point opposite Culp's Hill. Thus, the Union army had interior lines, while the Confederate line was nearly five miles (8 km) long.[54]

Lee's battle plan for July 2 called for a general assault of Meade's positions. On the right, Longstreet's First Corps was to position itself to attack the Union left flank, facing northeast astraddle the Emmitsburg Road, and to roll up the Union line. The attack sequence was to begin with Maj. Gens. John Bell Hood's and Lafayette McLaws's divisions, followed by Major General Richard H. Anderson's division of Hill's Third Corps.[55]

On the left, Lee instructed Ewell to position his Second Corps to attack Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill when he heard the gunfire from Longstreet's assault, preventing Meade from shifting troops to bolster his left. Though it does not appear in either his or Lee's Official Report, Ewell claimed years later that Lee had changed the order to simultaneously attack, calling for only a "diversion", to be turned into a full-scale attack if a favorable opportunity presented itself.[56][57]

Lee's plan, however, was based on faulty intelligence, exacerbated by Stuart's continued absence from the battlefield. Though Lee personally reconnoitered his left during the morning, he did not visit Longstreet's position on the Confederate right. Even so, Lee rejected suggestions that Longstreet move beyond Meade's left and attack the Union flank, capturing the supply trains and effectively blocking Meade's escape route.[58]

Lee did not issue orders for the attack until 11:00 a.m.[55][fn 3] About noon, General Anderson's advancing troops were discovered by General Sickles's outpost guard and the Third Corps—upon which Longstreet's First Corps was to form—did not get into position until 1:00 p.m.[60]

Hood and McLaws, after their long march, were not yet in position and did not launch their attacks until just after 4 p.m. and 5 p.m., respectively.[61]

Attacks on the Union left flank

As Longstreet's left division, under Major General Lafayette McLaws, advanced, they unexpectedly found Major General Daniel Sickles's III Corps directly in their path. Sickles had been dissatisfied with the position assigned him on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge. Seeing ground better suited for artillery positions one-half mile (800 m) to the west—centered at the Sherfy farm's Peach Orchard—he violated orders and advanced his corp to the slightly higher ground along the Emmitsburg Road, moving away from Cemetery Ridge. The new line ran from Devil's Den, northwest to the Peach Orchard, then northeast along the Emmitsburg Road to south of the Codori farm. This created an untenable salient at the Peach Orchard; Brigadier General Andrew A. Humphreys's division (in position along the Emmitsburg Road) and Major General David B. Birney's division (to the south) were subject to attacks from two sides and were spread out over a longer front than their small corps could defend effectively.[62] The Confederate artillery was ordered to open fire at 3:00 p.m.[63] After failing to attend a meeting at this time of Meade's corps commanders, Meade rode to Sickles's position and demanded an explanation of the situation. Knowing a Confederate attack was imminent and a retreat would be endangered, Meade refused Sickles' offer to withdraw.[64]

Meade was forced to send 20,000 reinforcements:[65] the entire V Corps, Brigadier General John C. Caldwell's division of the II Corps, most of the XII Corps, and portions of the newly arrived VI Corps. Hood's division moved more to the east than intended, losing its alignment with the Emmitsburg Road,[66] attacking Devil's Den and Little Round Top. McLaws, coming in on Hood's left, drove multiple attacks into the thinly stretched III Corps in the Wheatfield and overwhelmed them in Sherfy's Peach Orchard. McLaws's attack eventually reached Plum Run Valley (the "Valley of Death") before being beaten back by the Pennsylvania Reserves division of the V Corps, moving down from Little Round Top. The III Corps was virtually destroyed as a combat unit in this battle, and Sickles's leg was amputated after it was shattered by a cannonball. Caldwell's division was destroyed piecemeal in the Wheatfield. Anderson's division, coming from McLaws's left and starting forward around 6 p.m., reached the crest of Cemetery Ridge, but could not hold the position in the face of counterattacks from the II Corps, including an almost suicidal bayonet charge by the 1st Minnesota regiment against a Confederate brigade, ordered in desperation by Hancock to buy time for reinforcements to arrive.[67]

As fighting raged in the Wheatfield and Devil's Den, Colonel Strong Vincent of V Corps had a precarious hold on Little Round Top, an important hill at the extreme left of the Union line. His brigade of four relatively small regiments was able to resist repeated assaults by Law's brigade of Hood's division. Meade's chief engineer, Brigadier General Gouverneur K. Warren, had realized the importance of this position, and dispatched Vincent's brigade, an artillery battery, and the 140th New York to occupy Little Round Top mere minutes before Hood's troops arrived. The defense of Little Round Top with a bayonet charge by the 20th Maine, ordered by Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain and possibly led down the slope by Lieutenant Holman S. Melcher, was one of the most fabled episodes in the Civil War and propelled Chamberlain into prominence after the war.[68][fn 4]

Attacks on the Union right flank

Ewell interpreted his orders as calling only for a cannonade.[57] His 32 guns, along with A. P. Hill's 55 guns, engaged in a two-hour artillery barrage at extreme range that had little effect. Finally, about six o'clock, Ewell sent orders to each of his division commanders to attack the Union lines in his front.[69]

Major General Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's Division had contemplated an assault on Culp's Hill, but they were still a mile away and had Rock Creek to cross. The few possible crossings would make significant delays. Because of this, only three of Johnson's four brigades moved to the attack.[69] Most of the hill's defenders, the Union XII Corps, had been sent to the left to defend against Longstreet's attacks, leaving only a brigade of New Yorkers under Brigadier General George S. Greene behind strong, newly constructed defensive works. With reinforcements from the I and XI Corps, Greene's men held off the Confederate attackers, though giving up some of the lower earthworks on the lower part of Culp's Hill.[70]

Early was similarly unprepared when he ordered Harry T. Hays's and Isaac E. Avery's brigades to attack the Union XI Corps positions on East Cemetery Hill. Once started, fighting was fierce: Colonel Andrew L. Harris of the Union 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, XI Corps came under a withering attack, losing half his men. Avery was wounded early on, but the Confederates reached the crest of the hill and entered the Union breastworks, capturing one or two batteries. Seeing he was not supported on his right, Hays withdrew. His right was to be supported by Robert E. Rodes's Division, but Rodes—like Early and Johnson—had not been ordered up in preparation for the attack. He had twice as far to travel as Early; by the time he came in contact with the Union skirmish line, Early's troops had already begun to withdraw.[71]

Jeb Stuart and his three cavalry brigades arrived in Gettysburg around noon but had no role in the second day's battle. Brigadier General Wade Hampton's brigade fought a minor engagement with newly promoted 23-year-old Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer's Michigan cavalry near Hunterstown to the northeast of Gettysburg.[72]

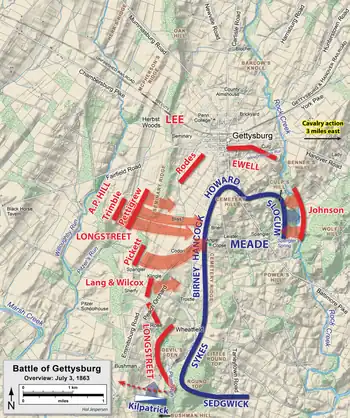

Third day of battle

Lee's plan

Lee wished to renew the attack on Friday, July 3, using the same basic plan as the previous day: Longstreet would attack the Union left, while Ewell attacked Culp's Hill.[73] However, before Longstreet was ready, Union XII Corps troops started a dawn artillery bombardment against the Confederates on Culp's Hill in an effort to regain a portion of their lost works. The Confederates attacked, and the second fight for Culp's Hill ended around 11 a.m. Harry Pfanz judged that, after some seven hours of bitter combat, "the Union line was intact and held more strongly than before".[74]

Lee was forced to change his plans. Longstreet would command Pickett's Virginia division of his own First Corps, plus six brigades from Hill's Corps, in an attack on the Union II Corps position at the right center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. Prior to the attack, all the artillery the Confederacy could bring to bear on the Union positions would bombard and weaken the enemy's line.[75]

Much has been made over the years of General Longstreet's objections to General Lee's plan. In his memoirs, Longstreet states that he told Lee that there were not enough men to assault the strong left center of the Union line by McLaws's and Hood's divisions reinforced by Pickett's brigades. Longstreet thought the attack would be repulsed and a counterattack would put Union forces between the Confederates and the Potomac River. Longstreet wrote that he said it would take a minimum of thirty thousand men to attack successfully as well as close coordination with other Confederate forces. He noted that only about thirteen thousand men were left in the selected divisions after the first two days of fighting. They would have to walk a mile under heavy artillery and long-range musketry fire. Longstreet states that he further asked Lee: "the strength of the column. He [Lee] stated fifteen thousand. Opinion was then expressed [by Longstreet] that the fifteen thousand men who could make successful assault over that field had never been arrayed for battle; but he was impatient of listening, and tired of talking, and nothing was left but to proceed."[76][fn 5]

Largest artillery bombardment of the war

Around 1 p.m., from 150 to 170 Confederate guns began an artillery bombardment that was probably the largest of the war. In order to save valuable ammunition for the infantry attack that they knew would follow, the Army of the Potomac's artillery, under the command of Brigadier General Henry Jackson Hunt, at first did not return the enemy's fire. After waiting about 15 minutes, about 80 Union cannons opened fire. The Army of Northern Virginia was critically low on artillery ammunition, and the cannonade did not significantly affect the Union position.[77]

Pickett's Charge

Around 3 p.m.,[78] the cannon fire subsided, and between 10,500 and 12,500 Southern soldiers[fn 6] stepped from the ridgeline and advanced the three-quarters of a mile (1,200 m) to Cemetery Ridge.[79] A more accurate name for the charge would be the "Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Charge" after the commanders of the three divisions taking part in the charge, but the role of Pickett's division has led to the attack generally being known as "Pickett's Charge".[80] As the Confederates approached, there was fierce flanking artillery fire from Union positions on Cemetery Hill and the Little Round Top area,[81] and musket and canister fire from Hancock's II Corps.[82] In the Union center, the commander of artillery had held fire during the Confederate bombardment (in order to save it for the infantry assault, which Meade had correctly predicted the day before), leading Southern commanders to believe the Northern cannon batteries had been knocked out. However, they opened fire on the Confederate infantry during their approach with devastating results.[83]

Although the Union line wavered and broke temporarily at a jog called the "Angle" in a low stone fence, just north of a patch of vegetation called the Copse of Trees, reinforcements rushed into the breach, and the Confederate attack was repelled. The farthest advance, by Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead's brigade of Pickett's division at the Angle, is referred to as the "high-water mark of the Confederacy".[84] Union and Confederate soldiers locked in hand-to-hand combat, attacking with their rifles, bayonets, rocks and even their bare hands. Armistead ordered his Confederates to turn two captured cannons against Union troops, but discovered that there was no ammunition left, the last double canister shots having been used against the charging Confederates. Armistead was mortally wounded shortly afterward. Nearly one half of the Confederate attackers did not return to their own lines.[85] Pickett's division lost about two thirds of its men, and all three brigadiers were killed or wounded.[83]

Cavalry battles

There were two significant cavalry engagements on July 3. The first one was coordinated with Pickett's Charge, and the standoff may have prevented a disaster for Union infantry.[86] The site of this engagement is now known as the East Cavalry Field.[87] The second engagement was a loss for Union cavalry attacking Confederate infantry. It has been labeled as a "fiasco", and featured faulty cavalry tactics.[88] The site of this engagement is now known as the South Cavalry Field.[89]

Northeast of Gettysburg

Stuart's cavalry division (three brigades), with the assistance of Jenkins' brigade, was sent to guard the Confederate left flank. Stuart was also in position to exploit any success the Confederate infantry (Pickett's Charge) might achieve on Cemetery Hill by flanking the Union right and getting behind Union infantry facing the Confederate attack.[90] The cavalry fight took place about three miles (4.8 km) northeast of Gettysburg at about 3:00 pm—around the end of the Confederate artillery barrage that preceded Pickett's charge. Stuart's forces collided with Union cavalry: Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg's division and Custer's brigade from Kilpatrick's division.[91] The fight evolved into "a wild melee of swinging sabers and blazing pistols and carbines".[92] One of Custer's regiments, the 5th Michigan Cavalry Regiment, was armed with Spencer repeating rifles, and at least two companies from an additional regiment were also armed with repeaters.[93] The fight ended in a standoff, as neither side changed positions. However, Gregg and Custer prevented Stuart from gaining the rear of Union infantry facing Pickett.[86]

Southwest of Gettysburg

After hearing news of the Union's success against Pickett's charge, Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick launched a cavalry attack against the infantry positions of Longstreet's Corps southwest of Big Round Top. The terrain was difficult for a mounted attack because it was rough, heavily wooded, and contained huge boulders—and Longstreet's men were entrenched with artillery support.[94] Brigadier General Elon J. Farnsworth protested against the futility of such a move, but obeyed orders. Farnsworth was killed in the fourth of five unsuccessful attacks, and his brigade suffered significant losses.[95] Although Kilpatrick was described by at least one Union leader as "brave, enterprising, and energetic", incidents such as Farnsworth's charge earned him the nickname of "Kill Cavalry".[96]

Aftermath

Casualties

The two armies suffered between 46,000 and 51,000 casualties.[fn 7] Union casualties were 23,055 (3,155 killed, 14,531 wounded, 5,369 captured or missing),[8][fn 8] while Confederate casualties are more difficult to estimate. Many authors have referred to as many as 28,000 Confederate casualties,[fn 9] and Busey and Martin's more recent 2005 work, Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, documents 23,231 (4,708 killed, 12,693 wounded, 5,830 captured or missing).[9] Nearly a third of Lee's general officers were killed, wounded, or captured.[98] The casualties for both sides for the 6-week campaign, according to Sears, were 57,225.[99]

In addition to being the deadliest battle of the war, Gettysburg also had the most generals killed in action. Several generals also were wounded. The Confederacy lost generals Paul Jones Semmes, William Barksdale, William Dorsey Pender, Richard Garnett, and Lewis Armistead, as well as J. Johnston Pettigrew during the retreat after the battle. Confederate generals who were wounded included Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood who lost the use of his left arm and Maj. Gen. Henry Heth who received a shot to the head on the first day of battle (though incapacitated for the rest of the battle, he remarkably survived without long-term injuries, credited in part due to his hat stuffed full of paper dispatches). Confederate generals James L. Kemper and Isaac R. Trimble were severely wounded during Pickett's charge and captured during the Confederate retreat. Confederate Brig. Gen. James J. Archer, in command of a brigade that most likely was responsible for killing Reynolds, was taken prisoner shortly after Reynolds' death. In the Confederate 1st Corps, eight of Longstreet's fourteen division and brigade commanders were killed or wounded, including Brig. Gen. George T. Anderson and Brig. Gen. Jerome B. Robertson, who were wounded. In Ewell's 2nd Corps, Brig. Gen. Isaac E. Avery was mortally wounded and Brig. Gen. John M. Jones was wounded. In Hill's 3rd Corps, in addition to Pender and Pettigrew being killed, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth and Col. Birkett D. Fry (later brigadier general), in temporary brigade command were wounded. In Hill's 3rd Corp, Brig. Gen. Alfred M. Scales and Col. William L. J. Lowrance, in temporary brigade command, were wounded. In the Confederate Cavalry Division, Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton and Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins were wounded.[100]

Union generals killed were John Reynolds, Samuel K. Zook, and Stephen H. Weed, as well as Elon J. Farnsworth, assigned as brigadier general by Maj. Gen. Pleasanton based on his nomination although his promotion was confirmed posthumously, and Strong Vincent, who after being mortally wounded was given a deathbed promotion to brigadier general. Additional senior officer casualties included the wounding of Union Generals Dan Sickles (lost a leg), Francis C. Barlow, Daniel Butterfield, and Winfield Scott Hancock. Five of seven brigade commanders in Reynolds's First Corps were wounded. In addition to Hancock and Brig. Gen. John Gibbon being wounded in the Second Corps, three of ten brigade commanders were killed and three were wounded.[101]

The following tables summarize casualties by corps for the Union and Confederate forces during the three-day battle, according to Busey and Martin.[102]

| Union Corps | Casualties (k/w/m) |

|---|---|

| I Corps | 6059 (666/3231/2162) |

| II Corps | 4369 (797/3194/378) |

| III Corps | 4211 (593/3029/589) |

| V Corps | 2187 (365/1611/211) |

| VI Corps | 242 (27/185/30) |

| XI Corps | 3801 (369/1922/1510) |

| XII Corps | 1082 (204/812/66) |

| Cavalry Corps | 852 (91/354/407) |

| Artillery Reserve | 242 (43/187/12) |

| Confederate Corps | Casualties (k/w/m) |

|---|---|

| First Corps | 7665 (1617/4205/1843) |

| Second Corps | 6686 (1301/3629/1756) |

| Third Corps | 8495 (1724/4683/2088) |

| Cavalry Corps | 380 (66/174/140) |

Bruce Catton wrote, "The town of Gettysburg looked as if some universal moving day had been interrupted by catastrophe."[103] But there was only one documented civilian death during the battle: Ginnie Wade (also widely known as Jennie), 20 years old, was hit by a stray bullet that passed through her kitchen in town while she was making bread.[104] Another notable civilian casualty was John L. Burns, a 69-year old veteran of the War of 1812 who walked to the front lines on the first day of battle and participated in heavy combat as a volunteer, receiving numerous wounds in the process. Though aged and injured, Burns survived the battle and lived until 1872.[105] Nearly 8,000 had been killed outright; these bodies, lying in the hot summer sun, needed to be buried quickly. More than 3,000 horse carcasses[106] were burned in a series of piles south of town; townsfolk became violently ill from the stench.[107] Meanwhile, the town of Gettysburg, with its population of just 2,400, found itself tasked with taking care of 14,000 wounded Union troops and an additional 8,000 Confederate prisoners.[108]

Confederates lost over 31–55 battle flags, with the Union possibly having lost slightly less than 40.[109]

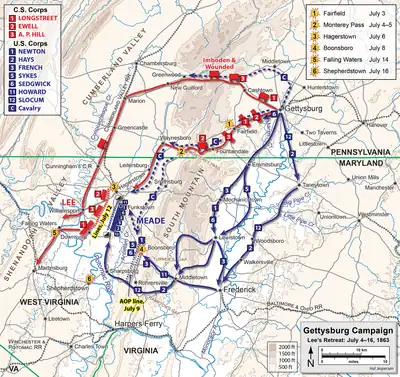

Confederate retreat

On the morning of July 4, with Lee's army still present, Meade ordered his cavalry to get to the rear of Lee's army.[110] In a heavy rain, the armies stared at one another across the bloody fields, on the same day that, some 920 miles (1,480 km) away, the Vicksburg garrison surrendered to Major General Ulysses S. Grant. Lee had reformed his lines into a defensive position on Seminary Ridge the night of July 3, evacuating the town of Gettysburg. The Confederates remained on the battlefield's west side, hoping that Meade would attack, but the cautious Union commander decided against the risk, a decision for which he would later be criticized. Both armies began to collect their remaining wounded and bury some of the dead. A proposal by Lee for a prisoner exchange was rejected by Meade.[111]

Late in the rainy afternoon, Lee started moving the non-fighting portion of his army back to Virginia. Cavalry under Brigadier General John D. Imboden was entrusted to escort the seventeen-mile long wagon train of supplies and wounded men, using a long route through Cashtown and Greencastle to Williamsport, Maryland. After sunset, the fighting portion of Lee's army began its retreat to Virginia using a more direct (but more mountainous) route that began on the road to Fairfield.[112] Although Lee knew exactly what he needed to do, Meade's situation was different. Meade needed to remain at Gettysburg until he was certain Lee was gone. If Meade left first, he could possibly leave an opening for Lee to get to Washington or Baltimore. In addition, the army that left the battlefield first was often considered the defeated army.[113]

"Now, if General Meade can complete his work so gloriously prosecuted thus far, by the literal or substantial destruction of Lee's army, the rebellion will be over."

Abraham Lincoln[114]

Union cavalry had some minor successes pursuing Lee's army. The first major encounter took place in the mountains at Monterey Pass on July 4, where Kilpatrick's cavalry division captured 150 to 300 wagons and took 1,300 to 1,500 prisoners.[115] Beginning July 6, additional cavalry fighting took place closer to the Potomac River in Maryland's Williamsport-Hagerstown area.[116] Lee's army was trapped and delayed from crossing the Potomac River because rainy weather had caused the river to swell, and the pontoon bridge at Falling Waters had been destroyed.[fn 10] Meade's infantry did not fully pursue Lee until July 7, and despite repeated pleas from Lincoln and Halleck, was not aggressive enough to destroy Lee's army.[118] A new pontoon bridge was constructed at Falling Waters, and lower water levels allowed the Confederates to begin crossing after dark on July 13.[119] Although Meade's infantry had reached the area on July 12, it was his cavalry that attacked the Confederate rear guard on the morning of July 14. Union cavalry took 500 prisoners, and Confederate Brigadier General Pettigrew was mortally wounded, but Lee's army completed its Potomac crossing.[120] The campaign continued south of the Potomac until the Battle of Manassas Gap on July 23, when Lee escaped and Meade abandoned the pursuit.[121]

Union reaction to the news of the victory

The news of the Union victory electrified the North. A headline in The Philadelphia Inquirer proclaimed "VICTORY! WATERLOO ECLIPSED!" New York diarist George Templeton Strong wrote:[122]

The results of this victory are priceless. ... The charm of Robert E. Lee's invincibility is broken. The Army of the Potomac has at last found a general that can handle it, and has stood nobly up to its terrible work in spite of its long disheartening list of hard-fought failures. ... Copperheads are palsied and dumb for the moment at least. ... Government is strengthened four-fold at home and abroad.

— George Templeton Strong, Diary, p. 330.

However, the Union enthusiasm soon dissipated as the public realized that Lee's army had escaped destruction and the war would continue. Lincoln complained to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that "Our army held the war in the hollow of their hand and they would not close it!"[123] Brigadier General Alexander S. Webb wrote to his father on July 17, stating that such Washington politicians as "Chase, Seward and others," disgusted with Meade, "write to me that Lee really won that Battle!"[124]

Effect on the Confederacy

In fact, the Confederates had lost militarily and also politically. During the final hours of the battle, Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens was approaching the Union lines at Norfolk, Virginia, under a flag of truce. Although his formal instructions from Confederate President Jefferson Davis had limited his powers to negotiate on prisoner exchanges and other procedural matters, historian James M. McPherson speculates that he had informal goals of presenting peace overtures. Davis had hoped that Stephens would reach Washington from the south while Lee's victorious army was marching toward it from the north. President Lincoln, upon hearing of the Gettysburg results, refused Stephens's request to pass through the lines. Furthermore, when the news reached London, any lingering hopes of European recognition of the Confederacy were finally abandoned. Henry Adams, whose father was serving as the U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom at the time, wrote, "The disasters of the rebels are unredeemed by even any hope of success. It is now conceded that all idea of intervention is at an end."[125]

Compounding the effects of the defeat was the end of the Siege of Vicksburg, which surrendered to Grant's Federal armies in the West on July 4, the day after the Gettysburg battle, costing the Confederacy an additional 30,000 men, along with all their arms and stores.[126]

The immediate reaction of the Southern military and public sectors was that Gettysburg was a setback, not a disaster. The sentiment was that Lee had been successful on July 1 and had fought a valiant battle on July 2–3, but could not dislodge the Union Army from the strong defensive position to which it fled. The Confederates successfully stood their ground on July 4 and withdrew only after they realized Meade would not attack them. The withdrawal to the Potomac that could have been a disaster was handled masterfully. Furthermore, the Army of the Potomac had been kept away from Virginia farmlands for the summer and all predicted that Meade would be too timid to threaten them for the rest of the year. Lee himself had a positive view of the campaign, writing to his wife that the army had returned "rather sooner than I had originally contemplated, but having accomplished what I proposed on leaving the Rappahannock, viz., relieving the Valley of the presence of the enemy and drawing his Army north of the Potomac". He was quoted as saying to Maj. John Seddon, brother of the Confederate secretary of war, "Sir, we did whip them at Gettysburg, and it will be seen for the next six months that that army will be as quiet as a sucking dove." Some Southern publications, such as the Charleston Mercury, were critical of Lee's actions. On August 8, Lee offered his resignation to President Davis, who quickly rejected it.[127]

Gettysburg Address

The ravages of war were still evident in Gettysburg more than four months later when, on November 19, the Soldiers' National Cemetery was dedicated. During this ceremony, President Lincoln honored the fallen and redefined the purpose of the war in his historic Gettysburg Address.[130][fn 11]

Medal of Honor

There were 72 Medals of Honor awarded for the Gettysburg Campaign, 64 of which were for actions taken during the battle itself. The first recipient was awarded in December 1864, while the most recent was posthumously awarded to Lieutenant Alonzo Cushing in 2014.[131]

Historical assessment

Decisive victory controversies

The nature of the result of the Battle of Gettysburg has been the subject of controversy. Although not seen as overwhelmingly significant at the time, particularly since the war continued for almost two years, in retrospect it has often been cited as the "turning point", usually in combination with the fall of Vicksburg the following day.[14] This is based on the observation that, after Gettysburg, Lee's army conducted no more strategic offensives—his army merely reacted to the initiative of Ulysses S. Grant in 1864 and 1865—and by the speculative viewpoint of the Lost Cause writers that a Confederate victory at Gettysburg might have resulted in the end of the war.[132]

[The Army of the Potomac] had won a victory. It might be less of a victory than Mr. Lincoln had hoped for, but it was nevertheless a victory—and, because of that, it was no longer possible for the Confederacy to win the war. The North might still lose it, to be sure, if the soldiers or the people should lose heart, but outright defeat was no longer in the cards.

Bruce Catton, Glory Road[133]

It is currently a widely held view that Gettysburg was a decisive victory for the Union, but the term is considered imprecise. It is inarguable that Lee's offensive on July 3 was turned back decisively and his campaign in Pennsylvania was terminated prematurely (although the Confederates at the time argued that this was a temporary setback and that the goals of the campaign were largely met). However, when the more common definition of "decisive victory" is intended—an indisputable military victory of a battle that determines or significantly influences the ultimate result of a conflict—historians are divided. For example, David J. Eicher called Gettysburg a "strategic loss for the Confederacy" and James M. McPherson wrote that "Lee and his men would go on to earn further laurels. But they never again possessed the power and reputation they carried into Pennsylvania those palmy summer days of 1863."[134]

However, Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones wrote that the "strategic impact of the Battle of Gettysburg was ... fairly limited." Steven E. Woodworth wrote that "Gettysburg proved only the near impossibility of decisive action in the Eastern theater." Edwin Coddington pointed out the heavy toll on the Army of the Potomac and that "after the battle Meade no longer possessed a truly effective instrument for the accomplishments of his task. The army needed a thorough reorganization with new commanders and fresh troops, but these changes were not made until Grant appeared on the scene in March 1864." Joseph T. Glatthaar wrote that "Lost opportunities and near successes plagued the Army of Northern Virginia during its Northern invasion," yet after Gettysburg, "without the distractions of duty as an invading force, without the breakdown of discipline, the Army of Northern Virginia [remained] an extremely formidable force." Ed Bearss wrote, "Lee's invasion of the North had been a costly failure. Nevertheless, at best the Army of the Potomac had simply preserved the strategic stalemate in the Eastern Theater ..."[135] Historian Alan Guelzo notes that Gettysburg and Vicksburg did not end the war and that the war would go on for two more years.[136] He also noted that a little more than a year later Federal armies appeared hopelessly mired in sieges at Petersburg and Atlanta.[137]

Peter Carmichael refers to the military context for the armies, the "horrendous losses at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, which effectively destroyed Lee's offensive capacity," implying that these cumulative losses were not the result of a single battle. Thomas Goss, writing in the U.S. Army's Military Review journal on the definition of "decisive" and the application of that description to Gettysburg, concludes: "For all that was decided and accomplished, the Battle of Gettysburg fails to earn the label 'decisive battle'."[138] The military historian John Keegan agrees. Gettysburg was a landmark battle, the largest of the war and it would not be surpassed. The Union had restored to it the belief in certain victory, and the loss dispirited the Confederacy. If "not exactly a decisive battle", Gettysburg was the end of Confederate use of Northern Virginia as a military buffer zone, the setting for Grant's Overland Campaign.[139]

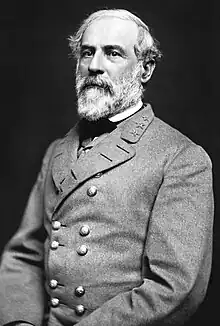

Lee vs. Meade

Prior to Gettysburg, Robert E. Lee had established a reputation as an almost invincible general, achieving stunning victories against superior numbers—although usually at the cost of high casualties to his army—during the Seven Days, the Northern Virginia Campaign (including the Second Battle of Bull Run), Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. Only the Maryland Campaign, with its tactically inconclusive Battle of Antietam, had been less than successful. Therefore, historians such as Fuller, Glatthaar, and Sears have attempted to explain how Lee's winning streak was interrupted so dramatically at Gettysburg.[140] Although the issue is tainted by attempts to portray history and Lee's reputation in a manner supporting different partisan goals, the major factors in Lee's loss arguably can be attributed to: (1) his overconfidence in the invincibility of his men; (2) the performance of his subordinates, and his management thereof; (3) his failing health; and, (4) the performance of his opponent, George G. Meade, and the Army of the Potomac.[141]

Throughout the campaign, Lee was influenced by the belief that his men were invincible; most of Lee's experiences with the Army of Northern Virginia had convinced him of this, including the great victory at Chancellorsville in early May and the rout of the Union troops at Gettysburg on July 1. Since morale plays an important role in military victory when other factors are equal, Lee did not want to dampen his army's desire to fight and resisted suggestions, principally by Longstreet, to withdraw from the recently captured Gettysburg to select a ground more favorable to his army. War correspondent Peter W. Alexander wrote that Lee "acted, probably, under the impression that his troops were able to carry any position however formidable. If such was the case, he committed an error, such however as the ablest commanders will sometimes fall into." Lee himself concurred with this judgment, writing to President Davis, "No blame can be attached to the army for its failure to accomplish what was projected by me, nor should it be censured for the unreasonable expectations of the public—I am alone to blame, in perhaps expecting too much of its prowess and valor."[142]

The most controversial assessments of the battle involve the performance of Lee's subordinates. The dominant theme of the Lost Cause writers and many other historians is that Lee's senior generals failed him in crucial ways, directly causing the loss of the battle; the alternative viewpoint is that Lee did not manage his subordinates adequately, and did not thereby compensate for their shortcomings.[143] Two of his corps commanders—Richard S. Ewell and A.P. Hill—had only recently been promoted and were not fully accustomed to Lee's style of command, in which he provided only general objectives and guidance to their former commander, Stonewall Jackson; Jackson translated these into detailed, specific orders to his division commanders.[144] All four of Lee's principal commanders received criticism during the campaign and battle:[145]

- James Longstreet suffered most severely from the wrath of the Lost Cause authors, not the least because he directly criticized Lee in postbellum writings and became a Republican after the war. His critics accuse him of attacking much later than Lee intended on July 2, squandering a chance to hit the Union Army before its defensive positions had firmed up. They also question his lack of motivation to attack strongly on July 2 and 3 because he had argued that the army should have maneuvered to a place where it would force Meade to attack them. The alternative view is that Lee was in close contact with Longstreet during the battle, agreed to delays on the morning of July 2, and never criticized Longstreet's performance. (There is also considerable speculation about what an attack might have looked like before Dan Sickles moved the III Corps toward the Peach Orchard.)[146]

- J.E.B. Stuart deprived Lee of cavalry intelligence during a good part of the campaign by taking his three best brigades on a path away from the army's. This arguably led to Lee's surprise at Hooker's vigorous pursuit; the engagement on July 1 that escalated into the full battle prematurely; and it also prevented Lee from understanding the full disposition of the enemy on July 2. The disagreements regarding Stuart's culpability for the situation originate in the relatively vague orders issued by Lee, but most modern historians agree that both generals were responsible to some extent for the failure of the cavalry's mission early in the campaign.[147]

- Richard S. Ewell has been universally criticized for failing to seize the high ground on the afternoon of July 1. Once again the disagreement centers on Lee's orders, which provided general guidance for Ewell to act "if practicable". Many historians speculate that Stonewall Jackson, if he had survived Chancellorsville, would have aggressively seized Culp's Hill, rendering Cemetery Hill indefensible, and changing the entire complexion of the battle. A differently worded order from Lee might have made the difference with this subordinate.[148]

- A.P. Hill has received some criticism for his ineffective performance. His actions caused the battle to begin and then escalate on July 1, despite Lee's orders not to bring on a general engagement (although historians point out that Hill kept Lee well informed of his actions during the day). However, Hill's illness minimized his personal involvement in the remainder of the battle, and Lee took the explicit step of temporarily removing troops from Hill's corps and giving them to Longstreet for Pickett's Charge.[149]

In addition to Hill's illness, Lee's performance was affected by heart troubles, which would eventually lead to his death in 1870; he had been diagnosed with pericarditis by his staff physicians in March 1863, though modern doctors believe he had in fact suffered a heart attack.[150][151][152] As a final factor, Lee faced a new and formidable opponent in George G. Meade, and the Army of the Potomac fought well on its home territory. Although new to his army command, Meade deployed his forces relatively effectively; relied on strong subordinates such as Winfield S. Hancock to make decisions where and when they were needed; took great advantage of defensive positions; nimbly shifted defensive resources on interior lines to parry strong threats; and, unlike some of his predecessors, stood his ground throughout the battle in the face of fierce Confederate attacks.[153]

Lee was quoted before the battle as saying Meade "would commit no blunders on my front and if I make one ... will make haste to take advantage of it." That prediction proved to be correct at Gettysburg. Stephen Sears wrote, "The fact of the matter is that George G. Meade, unexpectedly and against all odds, thoroughly outgeneraled Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg." Edwin B. Coddington wrote that the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac received a "sense of triumph which grew into an imperishable faith in [themselves]. The men knew what they could do under an extremely competent general; one of lesser ability and courage could well have lost the battle."[154]

Meade had his own detractors as well. Similar to the situation with Lee, Meade suffered partisan attacks about his performance at Gettysburg, but he had the misfortune of experiencing them in person. Supporters of his predecessor, Hooker, lambasted Meade before the U.S. Congress's Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, where Radical Republicans suspected that Meade was a Copperhead and tried in vain to relieve him from command. Daniel E. Sickles and Daniel Butterfield accused Meade of planning to retreat from Gettysburg during the battle. Most politicians, including Lincoln, criticized Meade for what they considered to be his half-hearted pursuit of Lee after the battle. A number of Meade's most competent subordinates—Winfield S. Hancock, John Gibbon, Gouverneur K. Warren, and Henry J. Hunt, all heroes of the battle—defended Meade in print, but Meade was embittered by the overall experience.[155]

Battlefield preservation

M1857 12-Pounder "Napoleon" at Gettysburg National Military Park

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, September 2006 | |

| Location | Adams County, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Website | Park Home (NPS.gov) |

Gettysburg National Cemetery and Gettysburg National Military Park are maintained by the U.S. National Park Service as two of the nation's most revered historical landmarks. Although Gettysburg is one of the best known of all Civil War battlefields, it too faces threats to its preservation and interpretation. Many historically significant locations on the battlefield lie outside the boundaries of Gettysburg National Military Park and are vulnerable to residential or commercial development.[156]

Some preservation successes have emerged in recent years. Two proposals to open a casino at Gettysburg were defeated in 2006 and most recently in 2011, when public pressure forced the Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board to reject the proposed gambling hub at the intersection of Routes 15 and 30, near East Cavalry Field.[157] The American Battlefield Trust, formerly the Civil War Trust, also successfully purchased and transferred 95 acres (38 ha) at the former site of the Gettysburg Country Club to the control of the U.S. Department of the Interior in 2011.[158]

Less than half of the over 11,500 acres on the old Gettysburg Battlefield have been preserved for posterity thus far. The American Battlefield Trust and its partners have acquired and preserved 1,242 acres (5.03 km2) of the battlefield in more than 40 separate transactions from 1997 to mid-2023.[159] Some of these acres are now among the 4,998 acres (2,023 ha) of the Gettysburg National Military Park.[160] In 2015, the Trust made one of its most important and expensive acquisitions, paying $6 million for a four-acre (1.6 ha) parcel that included the stone house that Confederate General Robert E. Lee used as his headquarters during the battle. The Trust razed a motel, restaurant and other buildings within the parcel to restore Lee's headquarters and the site to their wartime appearance, adding interpretive signs. It opened the site to the public in October 2016.[161]

In popular culture

At the 50th anniversary Gettysburg reunion (1913), 50,000 veterans attended according to a 1938 Army Medical report.[163] Historian Carol Reardon writes that attendance included at least 35,000 Union veterans and though estimates of attendees ran as high as 56,000, only a few more than 7,000 Confederate veterans, most from Virginia and North Carolina, attended.[164] Some veterans re-enacted Pickett's Charge in a spirit of reconciliation, a meeting that carried great emotional force for both sides. There was a ceremonial mass hand-shake across a stone wall on Cemetery Ridge.[165][166]

At the 75th anniversary Gettysburg reunion (1938), 1,333 Union veterans and 479 Confederate veterans attended.[163][167]

Film records survive of two Gettysburg reunions, held on the battlefield, in 1913.[168] and 1938.[169]

The children's novel Window of Time (1991), by Karen Weinberg, tells the story of a boy transported by time travel from the 1980s to the Battle of Gettysburg.[170]

The Battle of Gettysburg was depicted in the 1993 film Gettysburg, based on Michael Shaara's 1974 novel The Killer Angels.[171] The film and novel focused primarily on the actions of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, John Buford, Robert E. Lee, and James Longstreet during the battle. The first day focused on Buford's cavalry defense, the second day on Chamberlain's defense at Little Round Top, and the third day on Pickett's Charge.

See also

- Gettysburg Cyclorama, a painting by the French artist Paul Philippoteaux depicting Pickett's Charge

- List of costliest American Civil War land battles

- Troop engagements of the American Civil War, 1863

Notes

- The Battle of Antietam, the culmination of Lee's first invasion of the North, had the largest number of casualties in a single day, about 23,000.

- Historians who address the matter disagree on whether any troopers in Buford's division, and especially in William Gamble's brigade, had repeating carbines or repeating rifles. It is a minority view and most historians present creditable arguments against it. In support of the minority view, Stephen D. Starr wrote that most of the troopers in flanking companies had Spencer carbines, which had arrived a few days before the battle.The Union Cavalry in the Civil War: From Fort Sumter to Gettysburg, 1861–1863. Volume 1, citing Buckeridge, J. O. Lincoln's Choice. Harrisburg, Stackpole Books, 1956, p. 55. Shelby Foote in Fredericksburg to Meridian, The Civil War: a Narrative, Volume 2 New York, 1963, ISBN 978-0-394-74621-0, p. 465, also stated that some Union troopers had Spencer carbines. Richard S. Shue also claimed that a limited distribution of Spencer rifles had been made to some of Buford's troopers in his book Morning at Willoughby Run Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1995, ISBN 978-0-939631-74-2 p. 214.

Edward G. Longacre wrote that in Gamble's brigade "a few squadrons of Federal troopers used [Spencer] repeating rifles" (rather than carbines) but most had single-shot breech-loading carbines. Longacre p. 60. Order of battle at Coddington, p. 585. Coddington, pp. 258-259, wrote that men in the 5th Michigan and at least two companies of the 6th Michigan regiment had Spencer repeating rifles (rather than carbines). Harry Hansen wrote that Thomas C. Devin's brigade of one Pennsylvania and three New York regiments "were equipped with new Spencer repeating carbines," without reference to Gamble's men. The Civil War: A History. New York: Bonanza Books, 1961. OCLC 500488542, p. 370.

David G. Martin, in Gettysburg July 1 stated that all of Buford's men had single-shot breech-loading carbines which could be fired 5 to 8 times per minute, and fired from a prone position, as opposed to 2 to 3 rounds per minute with muzzle-loaders, "an advantage but not a spectacular one". p. 82. Cavalry historian Eric J. Wittenberg in The Devil's to Pay: John Buford at Gettysburg: A History and Walking Tour. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2014, 2015, 2018. ISBN 978-1-61121-444-4, stated that "while it is possible a handful of Spencer repeating rifles were present at Gettysburg" it is safe to conclude that Buford's troopers did not have them. He cited the fact that "only 64 percent of the companies in Gamble's and Devin's brigades filed their quarterly returns on June 30, 1863" in support of the possibility that some had repeaters but gave reasons for his rejection of that possibility. He dismissed Shelby Foote's statement as "mythology" because the Spencer carbines were not in mass production until September 1863, stated that Longacre credits Spencer repeating rifles to different regiments than the ordnance returns for the Army of the Potomac do, and discounted Shue's statement because he used "an unreliable source". pp. 209-210.

In their books on the battle or on the war as a whole, many historians have not commented directly on whether any Federal troopers had repeating carbines or rifle. Some of them, such as Harry Pfanz, First Day, p. 67 specifically mentioned that the Union cavalry had breech-loading carbines enabling the troopers to fire slightly faster than soldiers with muzzle-loading rifles and made no mention of repeaters. Similar statements to that of Pfanz are found at Keegan, p. 191; Sears, p. 163; Eicher, p. 510; Symonds, p. 71, Hoptak, p. 53, Trudeau, p. 164. Others such as McPherson and Guelzo do not mention the weapons used by Buford's division. - Claims have been made that Lee intended for there to be an attack at sunrise, or at another point earlier in the day, but that the attack was delayed by Longstreet. Lee allegedly stated "What can detain Longstreet" not long after 9:00 am that morning, and Longstreet has been attributed as saying that "[Lee] wishes me to attack; I do not wish to do so without Pickett"; some writers have interpreted these statements as an indication that Lee intended the attack to take place earlier. Eicher rejects claims that Lee intended for the attack to begin at sunrise, although allowing that it is possible that Lee may have intended for an earlier attack. Eicher concludes that "preparations for the attack did not get underway until between 11 A.M. and noon". Sears notes that Lee "was said to be exasperated" by the late start of the attack, but also states that "having made plain by his orders to McLaws that he was assuming tactical command of the operation, Lee had not issued any earlier start-up order".[59]

- Morgan, James. "Who saved Little Round Top?". Camp Chase Gazette. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

Morgan addresses and rebuts certain conclusions made in With a Flash of His Sword: The Writings of Major Holman S. Melcher, 20th Maine Infantry. Edited by William B. Styple. The full text of Morgan's analysis of Styples's "point number 4" about who ordered and lead the charges is: "Number 4. Col. Chamberlain did not lead the charge. Lt. Holman Melcher was the first officer down the slope [according to Styples]. Though directly related to Mr. Styples argument, this is a very minor point and could even be called a quibble. Even granting Melcher the honor of being first down the slope (and such an interpretation is perfectly plausible), he did not "lead" the charge in a command sense, which is what the conclusion implies. Chamberlain probably was standing in his proper place behind the line when he yelled "Bayonets!," so if indeed "the word was enough" to get the men started, he could not have gone first as the entire line would have moved out ahead of him. But it does not matter. The questions, "who was first down the hill?" and "who led the charge?" are different questions which should not be posed as one....The question, therefore, remains: who saved Little Round Top? Given the available historical evidence, the answer likewise must remain: Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain.

- Longstreet wrote in his memoirs that he estimated that his force would have "about thirteen thousand" men, not fifteen thousand. When asked by Longstreet the "strength of the column", Lee said the size would be fifteen thousand, which apparently included his estimate of the strength of two brigades of Anderson's Division of Hill's Third Corp that he would add to support Longstreet's men. Neither general knew the exact number of men available to attack at that tine because of casualties already sustained, merely the units. Longstreet did not write that he accepted that 15,000 would be the exact number of attackers. He merely said that no fifteen thousand men could take the Union position, that it would require 30,000. Historians give differing numbers of attackers for various reasons but all give numbers that are lower than 15,000 as shown in the next footnote.

- Writing about the number of attackers in the charge, Carol Reardon, in Pickett's Charge in History & Memory, at page 6, wrote "Modern histories have reduced the number to a range somewhere between 10,500 and 13,000. No one 'knows' the number." Eicher, The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, at p. 544 gives the same range as Reardon does for the number of attackers. Stephen W. Sears in Gettysburg at p. 407 wrote "...George Meade thus had some 13,000 troops - as it happened, just about the same number as stepped off in Pickett's Charge..." Alan C. Guelzo, in Gettysburg: The Last Invasion, at p. 393 wrote "There would be around 13,000 men in the attack, if all of them could be gotten to move." He also notes in a footnote that estimates of the number vary widely. Among those giving a higher numbers of attackers, neither Guelzo nor Sears appear to take into account Ed Bearss's statement in Receding Tide p. 366 that Confederate casualties from Union Army artillery "overshoot" into the Confederate soldiers staged behind the front line before the charge amounted to almost 600 men. George R. Stewart, in Pickett's Charge: A microhistory of the final attack at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863 (1959), p. 173, after totaling the strength in the divisions and brigades in the charge considering earlier losses gives the lowest estimate of "troops in the assaulting column...at 10,500." Gary W. Gallagher, Stephen D. Engle, Robert K. Krick & Joseph T. Glatthaar in The American Civil War: This Might Scourge of War at page 180 wrote "About 12,000 Confederates tried, in the most renowned attack in all of American military history." Earl J. Hess in Pickett's Charge–The Last Attack at Gettysburg p. 335 wrote of "11,830 men engaged" in the charge. Noah Andre Trudeau wrote in Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p. 477, that with the addition of the very late advance of the brigades of Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox and Brig. Gen. Edward A. Perry (led by Col. David Lang), the number of attackers could be said to approach 15,000, but with their subtraction, because the main charge had already been repulsed and accounting for Confederate casualties caused by Union Army artillery "overshoot", the number of attackers "approaches 11,800". Most references do not mention and cannot be adding about 1,400 men of the brigades of Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox and Brig. Gen. Edward Perry, led by Col. David Lang, who started after the main charge had been repulsed with great casualties. Lang's (Perry's) three Florida regiments suffered hundreds of casualties, including many taken prisoner. Wilcox saw the futility of the attack and ordered his men back when he discovered the main attack had been repulsed and they would receive no artillery or other support. The brigade lost about 200 men before turning back. Gottfried, pp. 581, 588. McPherson, p. 662, gives a larger number than other modern historians of 14,000 Confederates going forward in the charge, scarcely half of whom returned. This may count the Wilcox and Perry (Lang) brigades, although he does not mention them.

- McPherson, p. 664 states Union casualties were 23,000, "more than one-quarter of the army's effectives" and Confederate casualties were 28,000, "more than a third of Lee's army".

- The number of Union casualties stated by the U.S. Adjutant General in 1888 was 23,003 (3,042 killed, 14,497 wounded, 5,464 captured or missing). Drum, Richard C. United States. Adjutant-General's Office. Itinerary of the Army of the Potomac, and co-operating forces in the Gettysburg campaign, June 5 - July 31, 1863; organization of the Army of the Potomac and Army of northern Virginia at the battle of Gettysburg; and return of casualties in the Union and Confederate forces. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1888. OCLC 6512586. p. 45. Other Union casualty figures stated by later historians were similar, including Murray and Hsieh, p. 290, 22,625; Trudeau, p. 529, 22,813; McPherson, p. 664, 23,000; Walsh, p. 285, 23,000; Guelzo, p. 445, 24,000 as rounded up by Meade in his later testimony before the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Sears p. 496 states that the Union Army also suffered about 7,300 casualties at the Second Battle of Winchester on June 13–15, 1863 during Ewell's advance to Gettysburg and in the Union Army pursuit of the Confederate Army after the battle.

- Examples of the varying Confederate casualties for July 1–3 include Coddington, p. 536 (20,451, "and very likely more"). This is the same figure given by Drum, 1888, p. 69. Drum footnotes the casualty returns for some Confederate units as "Loss, if any, not recorded." For other units, he notes that brigade and regimental numbers sometimes differ and the brigade or larger Confederate unit totals are used. He states on p. 59 that the compilations of Confederate casualties can only be considered as "approximative". This lends weight to the higher numbers of Confederate casualties computed or estimated by historians including Busey and Martin cited in connection with the tables below, as well as Sears, p. 498 (22,625 plus just over 4,500 on the march north); Trudeau, p. 529 (22,874); Eicher, p. 550 (22,874, "but probably actually totaled 28,000 or more"); McPherson, p. 664 (28,000); Esposito, map 99 ("near 28,000"); Clark, p. 150 (20,448, "but probably closer to 28,000"); Woodworth, p. 209 ("at least equal to Meade's and possibly as high as 28,000"); NPS (28,000).

- Lee had left intact a pontoon bridge located at Falling Waters. This bridge had originally been used during the movement north into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Union cavalry under the command of Brigadier General William H. French destroyed the bridge on July 4. Lee's options for crossing the Potomac River were either a ferry at Williamsport that could handle only two wagons per crossing, or the Falling Waters location six miles (9.7 km) downstream.[117]

- White, p.251. refers to Lincoln's use of the term "new birth of freedom" and writes, "The new birth that slowly emerged in Lincoln's politics meant that on November 19 at Gettysburg he was no longer, as in his inaugural address, defending an old Union but proclaiming a new Union. The old Union contained and attempted to restrain slavery. The new Union would fulfill the promise of liberty, the crucial step into the future that the Founders had failed to take."

Citations