Acadiana

Acadiana (French and Louisiana French: L'Acadiane), also known as the Cajun Country (Louisiana French: Le Pays Cadjin, Spanish: País Cajún), is the official name given to the French Louisiana region that has historically contained much of the state's Francophone population.[1]

Acadiana

| |

|---|---|

Region | |

Downtown Lafayette, Louisiana | |

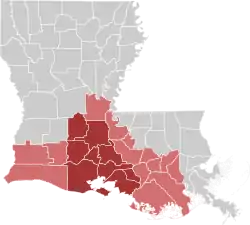

Map of Louisiana with Acadiana highlighted, and the heart of Acadiana in dark red | |

Location of Louisiana within the United States | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Legislative recognition | 1971 |

| Largest city | Lafayette |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 1,486,345 |

| Demonyms |

|

| Website | www |

Many inhabitants of the Cajun Country have Acadian ancestry and identify as Cajuns or Creoles.[2] Of the 64 parishes that make up the U.S. state of Louisiana, 22 named parishes and other parishes of similar cultural environment make up this intrastate region.[3][4]

Etymology

The word "Acadiana" reputedly has two origins. Its first recorded appearance dates to the October 15, 1946, when a Crowley, Louisiana, newspaper, the Crowley Daily Signal, coined the term in reference to the area of Louisiana in which French descendants of the Acadians settled.[5] However, KATC television in Lafayette independently coined "Acadiana" in the early 1960s, giving it a new, broader meaning, and popularized it throughout southern Louisiana. Founded in 1962, KATC was owned by the Acadian Television Corporation. In early 1963, the ABC affiliate received an invoice erroneously addressed to the "Acadiana" Television Corp. Someone had typed an extra "a" at the end of the word "Acadian". The station started using it to describe the region covered by its broadcast signal.[6]

Today, numerous business, governmental, and nonprofit organizations incorporate Acadiana in their names, e.g., Mall of Acadiana and Acadiana High School. Notably, KLFY-TV, the regional CBS affiliate, used the term in its very successful "Hello News" branding campaign as "Hello Acadiana". KATC hosts a morning television show, "Good Morning Acadiana".[7]

History

Historically part of French Louisiana, present-day Acadiana was inhabited by Attakapa Native Americans at the time of European encounter.[8] After the expulsion of French-speaking Acadian refugees from Canada by the victorious British at the end of the Seven Years' War, many Acadians settled in this region.[9][10] The Acadians intermarried with other settlers, forming what became known as Cajun culture.[11]

In 1971, the Louisiana State Legislature officially recognized 22 Louisiana parishes and "other parishes of similar cultural environment" for their "strong French Acadian cultural aspects" (House Concurrent Resolution No. 496, June 6, 1971, authored by Carl W. Bauer of St. Mary Parish). It made "Heart of Acadiana" the official name of the region. The public, however, prefers using Acadiana to refer to the region.[12] The official term appears on regional maps and highway markers.

Effects of hurricanes

Like much of Louisiana, this area is subject to damaging hurricanes. On October 3, 2002,[13] the central Acadiana region suffered a direct hit from category one Hurricane Lili.[14] The hurricane caused most of Acadiana to lose power, and some areas lost phone service. In addition, some high-rise buildings in downtown Lafayette had windows broken, and the roofs were damaged of many homes throughout the region. The high winds of Lili toppled the tower of KLFY TV-10 onto the station's studio facilities. Only one injury inside the station was reported from the tower's collapse.

The eastern Acadiana region was somewhat affected by Hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005, although the damage was limited compared to the severe flooding farther east in Greater New Orleans. This area was used by many evacuees when they returned to the region as a "last stop" of temporary domicile before returning to Greater New Orleans. The Greater Baton Rouge area had already been handling numerous evacuees. Governor Kathleen Blanco made a public request that those returning not try to seek lodging in the capital due to this crisis of overpopulation.

Lafayette and several other municipalities set up both public and church-run shelters to handle the influx. The largest of these shelters, run by the Red Cross, was the Lafayette sports arena (the Cajundome), holding a reported 9,800 persons.[15]

The western Acadiana region and east Texas were most affected by Hurricane Rita which hit on September 24, 2005. The Greater Lake Charles metropolitan area suffered the majority of the damage.[16]

On Labor Day 2008, Hurricane Gustav caused severe damage to the region.[17][18] Although Lafayette, Saint Martinville and Crowley had little damage (comparatively) and some residents still had power, the rest of the region was severely affected. From Alexandria to the coast and Baton Rouge to Lake Charles,[19] massive power failures and flooding were reported. Most notable was the flooding south of Louisiana Highway 14 and the communities there. U.S. 90 was shut down for several days due to the flooding caused by Hurricane Gustav.

The total death toll from Hurricane Gustav in Acadiana was limited. This was attributed to the evacuation and mitigation plans that had been drilled by state and local official, and to a strong presence of representatives from both the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Emergency Management Agency. In total, almost two million people along the Louisiana coast were evacuated in over two days. Gustav preparations comprised the largest evacuation in Louisiana history, and one of the most successful evacuations in the nation's history.[20]

In 2020, hurricanes Laura and Delta caused significant damage to the western-most portion of Acadiana, including Calcasieu, Cameron, Jeff Davis, and portions of Vermilion and Acadia. A confirmed 18 people died in the storm and its aftermath. In addition, Intracoastal City saw a storm surge of 6 feet (1.8 m).[21] Storm surge also flooded over SH 317 at Burns Point in St. Mary Parish, and flash flooding surrounded homes in Abbeville.[22][23]

Six weeks later, Hurricane Delta made landfall near Creole, Louisiana, with winds of 100 mph. Virtually the same parishes were affected by Hurricanes Laura and Delta. Over 740,000 residents had no power following both storms.[24]

Geography

.jpg.webp)

Acadiana consists mainly of low gentle hills in the north section and dry land prairies, with marshes and bayous in the south closer to the Gulf Coast area. The wetlands increase in frequency in and around the Calcasieu River, Atchafalaya Basin, and the Mississippi River Delta. The area is cultivated with fields of rice and sugarcane.

Acadiana, as defined by the Louisiana legislature, refers to the area that stretches from just west of New Orleans to the Texas border along the Gulf of Mexico coast, and about 100 miles (160 km) inland to Marksville. This includes the 22 parishes of Acadia, Ascension, Assumption, Avoyelles, Calcasieu, Cameron, Evangeline, Iberia, Iberville, Jefferson Davis, Lafayette, Lafourche, Pointe Coupee, St. Charles, St. James, St. John The Baptist, St. Landry, St. Martin, St. Mary, Terrebonne, Vermilion, and West Baton Rouge.[25] The total land area of Acadiana is 14,574.105 square miles (37,746.76 square kilometers). If Acadiana was a U.S. state, it would be larger than Maryland; if it were a sovereign state, it would be larger than the Bahamas.

Three of the parishes (St. Charles, St. James, and St. John the Baptist) are considered the River Parishes and made up the area formerly known as the German Coast or les côtes des Allemands, because of settlement by German immigrants in the 18th century. Ascension Parish is sometimes included within the River Parishes; the River Parishes border the first and third largest regions in Louisiana by population (the Greater New Orleans area and Florida Parishes). St. James and Ascension parishes were originally known as the Comté d'Acadie (Acadia County) because of the initial settlement of 18th-century exiled Acadians. St. James Parish was known as the First Acadian Coast and Ascension Parish was known as the Second Acadian Coast. Collectively they were known as les côtes des Acadiens, the Acadian Coasts.

Major cities

The largest metropolitan areas in Acadiana are Lafayette, Lake Charles, and Houma-Thibodaux. Other cities and towns within Acadiana are Abbeville, Berwick, Breaux Bridge, Broussard, Bunkie, Carencro, Church Point, Crowley, Donaldsonville, Erath, Eunice, Franklin, Gonzales, Gueydan, Jeanerette, Jennings, Kaplan, Lutcher, Mamou, Marksville, Maurice, Morgan City, New Iberia, New Roads, Opelousas, Patterson, Plaquemine, Port Allen, Rayne, Scott, Simmesport, St. Gabriel, St. Martinville, Sulphur, Sunset, Ville Platte, and Youngsville.

Demographics

At the 2000 U.S. census the total population of Acadiana was 1,352,646 residents. At the 2019 American Community Survey, the tabulated population of Acadiana was an estimated 1,490,449. In 2020, the tabulated population of Acadiana's parishes was 1,486,345.

Cajun-Creole ethnicity

Cajuns are the descendants of 18th-century Acadian exiles from what are now Canada's Maritime Provinces, expelled by the British and New Englanders during and after the French and Indian War (see Expulsion of the Acadians).[2] They prevail among the region's visible cultures, but not everyone who lives in Acadiana is ethnically Acadian or speaks Louisiana French. Similarly, not everyone who is culturally "Cajun" is descended from the Acadian refugees.

German and Polish settlers found their way to this area as early as 1721, settling an area that became known as the German Coast. They preceded the Acadians. Acadiana is home to several Native American tribes, including the Chitimacha, Houma, Tunica-Biloxi, Attakapas, and Coushatta. Acadiana also is home to other ethnic groups, including Anglo-Americans, who came into the region in increasing numbers beginning notably with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Since the late 20th century, political refugees from Southeast Asia (Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia, among others) have brought their families, cultures, and languages to the area, and have contributed significantly to its fishing industry.

The region also boasts a large population of Creoles, descendants of the region's original settlers who arrived in Louisiana before and after the arrival of the Acadians. In the broadest sense, the term "Creole" has been used to denote anyone who is "native to Louisiana", regardless of race or ethnic origin. In this sense, Creoles can identify as black, white, and persons of mixed-race origin. The term has also come to denote cultural origins in addition to racial classification. While many in Acadiana associate Creoles specifically with those people descended from the gens de couleur libres (free people of color), others cling to the word's original definition, so Creoles of every ethnic background are still present in the region. Many Creoles also identify as Cajuns (and vice versa), whereas others reject association with one identity while still claiming the other. The two identities have never been mutually exclusive of one another, and documents written in Acadiana throughout the 19th century often make references to Acadiana's "Creole populations" that are understood to include people of Acadian descent.

Prior to the U.S. Civil War, Louisiana Creoles of color were a class of free people who either gained their freedom or were born into free families. The gens de couleur libres played an important role in the history of New Orleans and French Louisiana, both under French and Spanish occupation, and after the Louisiana Purchase by the United States. Some Creoles of color were wealthy businessmen, entrepreneurs, clothiers, real estate developers, doctors, and other respected professions; they owned estates and properties in French Louisiana.[26] Being a French, and later Spanish colony, Louisiana maintained a three-tiered society that was very similar to other Latin American and Caribbean countries.

In the colonial period of French and Spanish rule, men tended to marry later after becoming financially established. Men frequently took Native American women as their wives (see Marriage à la façon du pays), and as slaves were imported into the colony, settlers also took African wives. Intermarriage between the different groups of Louisiana created a large multiracial Creole population.

As more families settled Louisiana, young Frenchmen or French Creoles coming from wealthy backgrounds courted mixed-race women as their mistresses, known as placées, before they officially married. The gens de couleur libres developed formal arrangements for placées, which the young women's mothers negotiated. Under the system of plaçage, the suitor had to be wealthy and prove that he could support the daughter, and take care of their children. Often the mothers arranged a kind of dowry or property transfer to their daughters; if the daughter was a slave, she and their children would gain freedom. The fathers often paid for the education of their mixed-race children from plaçage relationships, especially if they were sons, generally sending them to France to be educated.[26]

Many descendants of the gens de couleur libres, or free people of color, of the Louisiana area celebrate their culture and heritage through a New Orleans-based Louisiana Creole Research Association (LA Créole).[27] The term Créole is not synonymous with "free people of color" or gens de couleur libres, but many members of LA Créole have traced their genealogies through those lines. Today, the multiracial descendants of the French and Spanish colonists, Africans, and other ethnicities are widely known as Louisiana Creoles. Louisiana's Governor Bobby Jindal signed Act 276 on 14 June 2013, creating the license plate "I'm Creole", honoring Louisiana Creoles' contributions and heritage.[28]

Similarly, the Acadiana region is home to many African Americans, who have contributed greatly to the region over the centuries. Many primarily descend from those persons brought to the State of Louisiana in various waves during the colonial period to work the area's sugarcane and rice plantations in the southern part of the state and the cotton plantations in the northern part of the state. Between 1723 and 1769, most slaves imported to Louisiana were from modern day Senegal, Mali and Congo, many thousands being imported to Louisiana from there.[29] A large number of the imported slaves from the Senegambia region were members of the Wolof and Bambara ethnic groups. Saint-Louis and Goree Island were sites where a great number of slaves destined for Louisiana departed from Africa.[30]

During the Spanish control of Louisiana, between 1770 and 1803, most of the slaves still came from the Congo and the Senegambia region, but others were imported from modern-day Benin.[31] Many slaves imported during this period were members of the Nago people, a Yoruba subgroup.[32] The slaves brought with them their cultural practices, languages, and religious beliefs rooted in spirit and ancestor worship, as well as Roman Catholic Christianity—all of which were key elements of Louisiana Voodoo.[31] In addition, in the early nineteenth century, many Saint Dominicans also settled in Louisiana, both free people of color and slaves, following the Haitian Revolution on Saint-Domingue, contributing to the Voodoo tradition of the state. During the American period (1804–1820), almost half of the slaves came from the Congo.[29][33] Before the American Civil War (1861–1865), African Americans comprised a significant portion of the state's population, with most being employed on sugar cane and cotton plantations (see history of slavery in Louisiana and Louisiana African American Heritage Trail).

Religion

Religiously, Acadiana differs from much of the American South because a majority of its people are Christians of the Roman Catholic tradition in contrast to the surrounding regions (e.g., Central and Northern Louisiana), which are part of the largely Protestant Bible Belt. This is largely attributed to the region's French, Spanish, and Caribbean influences. Among the Catholic population of Acadiana, the majority are served by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Lafayette in Louisiana,[34] though some areas in western and eastern Acadiana belong to the Diocese of Lake Charles,[35] and the Roman Catholic Diocese of Baton Rouge in the Florida Parishes.[36]

Transportation

The traditional industries of the area, agriculture, petroleum, and tourism, initially drove the need for transportation development. In recent years, hurricane evacuation plans for the area's growing towns and cities have hastened the planning and construction of better roadways. The abundance of swamps and marshes previously made Acadiana difficult to access, a major reason for the near isolation of the early Cajun people.

After oil was found in the area in the early 20th century, oil industry development was geared to improving access by roads and waterways. Damage has been done to the region by dredging and straightening of waterways, which has damaged the wetlands that used to absorb water and storms, leaving the area more vulnerable. Coastline continues to erode.[37]

Land

High-capacity, modern highways are the lifelines of the region. U.S. highways 90, 190, and 167 were the main connectors through south Louisiana until the 1950s. Interstates 10, 210, 55, and 49 now play the major role in transportation. US and state highways also cross the region.

Rail transport through the area is limited by the difficult terrain and the sheer number of bridges required to build over numerous streams and bayous. A robust railroad system was being built at the time of the American Civil War, but much of it was destroyed during the conflict. By the end of the war, river transport via paddlewheeler had taken over as the preferred mode of travel. The major railways in operation through the region are the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad.

Water

Waterways are vital to the commercial and recreational activities of the region. Seaports, rivers, lakes, bayous, canals, and spillways dot the landscape, and served as the primary source of shipping and travel through the early 1930s. The Mississippi River is important to the eastern section, the Atchafalaya River to the middle. Calcasieu River flowing through Lake Charles enables shipping traffic in the western portion, while the Sabine River forms the western border of both Acadiana and Louisiana. Fresh and saltwater lakes, along with almost the entire Louisiana portion of the Intracoastal Waterway, enable the flow of people and materials.

Air

Airports in Lafayette and Lake Charles provide scheduled airline service. Helicopter pilots serve the oilfields in the Gulf of Mexico. Small planes are used for short trips and agricultural needs. Small general aviation airports serve communities throughout the area.

See also

- Acadia

- French Louisiana (disambiguation page)

- List of Louisiana parishes by French-speaking population

- Acadian Coast

- Acadian Village

- Acadiana Profile magazine, established 1968 by Robert Angers

- The Independent (Acadiana) newspaper established 2003

- Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

- Southwest Louisiana

- Center for Louisiana Studies

References

- "Francophone Louisiana". 64 Parishes. December 9, 2014. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- "What Is Cajun - Explore Lafayette Louisiana". Lafayette Travel. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- Johnson, Sally (January 27, 1991). "The Cajun Kingdom Of the Bayou". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Acadiana". Acadiana Development. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- https://acadia.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=acadiana&i=f&by=1946&bdd=1940&d=01011886-12312022&m=between&ord=k1&fn=crowley_daily_signal_usa_louisiana_crowley_19461015_english_11&df=1&dt=1

- "Lafayette History". Lafayette Convention and Visitors Commission. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved December 6, 2006.

- "GMA". KATC. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- Martin, Michael S. (2007). Historic Lafayette : an illustrated history of Lafayette & Lafayette Parish. San Antonio, Tex.: Historical Pub. Network. pp. 5–7, 10, 11. ISBN 978-1-893619-76-0. OCLC 213465938.

- "From Acadian to Cajun - Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- "Timeline of the Acadians". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on August 29, 2004. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- "Cajuns". 64 Parishes. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- Shane K. Bernard, The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), p. 80.

- "A look at what could be in store for the rest of hurricane season in Acadiana". KLFY. September 22, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Hurricane Lili – October 2–6, 2002". Weather Prediction Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Remembering the Cajundome Mega-Shelter during 13th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina". KLFY. August 28, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Hurricane Rita: Louisiana". CBS News. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "Hurricane Gustav – September 1, 2008". National Weather Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Back to back: A look at 2008 hurricanes Gustav and Ike". KATC. May 24, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "City leaders reflect on Gustav 1 year later". KPLC TV. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "2008 – Hurricane Gustav". Hurricanes: Science and Society. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- Herzmann, Daryl. "IEM :: LSR from NWS LCH". Iowa State University. Archived from the original on September 5, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Herzmann, Daryl. "IEM :: LSR from NWS LCH". Iowa State University. Archived from the original on September 5, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Herzmann, Daryl. "IEM :: LSR from NWS LCH". Iowa State University. Archived from the original on September 5, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "Tracking the Tropics: Delta adds insult to injury in hurricane-ravaged Louisiana". WGNO. October 10, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- "Acadiana Delegation". house.louisiana.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- Gehman, Mary (2017). The Free People of Color of New Orleans (7th ed.). New Orleans: D'Ville Press LLC. pp. 59, 69, 70.

- "LA Creole". Louisiana Creole Research Association. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- Louisiana State Government website

- "Louisiana: most African diversity within the United States?". Tracing African Roots. September 25, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, Volume 2.

- Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo (1995). Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Louisiana State University Press. p. 58.

- Kein, Sybil, ed. (2000). Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana's Free People of Color. Louisiana State University Press.

- "The Louisiana Slave Database". Whitney Plantation. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- "Parishes". Roman Catholic Diocese of Lafayette, Louisiana. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Diocesan Parishes". Diocese of Lake Charles. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Parish Finder". Roman Catholic Diocese of Baton Rouge. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- Carl A. Brasseaux (May 18, 2011). Acadiana: Louisiana's Historic Cajun Country. Louisiana State University Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-8071-3965-3.